The Palestine Israel Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The United Nations and Palestinian Refugees the United Nations and Palestinian Refugees

UNRWA CONTACTS: Public Information Office Gaza HQ P.O. Box 140157 Amman, Jordan 11814 Tel.: +972 8 677 7527 Fax: +972 8 677 7697 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.unrwa.org UNHCR CONTACTS: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees 94, Rue de Montbrillant Case Postale 2500 CH-1211 Genève 2 Dépôt Switzerland Tel.: +41 22 739 8111 Fax: +41 22 739 7334 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.unhcr.org Front cover: Palestinians fleeing to Jordan,June 1967 / UNRWA Back cover: Tents had just been replaced by cement block houses at Khan Younis refugee camp, Gaza Strip, 1955 / UNRWA Inside cover: Baqa’a refugee camp, Jordan, 1969 / UNRWA Opposite: A Palestine refugee with her grandson in Beach refugee camp, Gaza Strip / UNRWA All UNRWA photographs courtesy of UNRWA Photo Archive & Steve Sabella January 2007 2 The United Nations and Palestinian Refugees The United Nations and Palestinian Refugees n December 1949, the United Nations General IAssembly established the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) to provide humanitarian relief to the more than 700,000 refugees and displaced persons who had been forced to flee their homes in Palestine as a result of the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. Also in December 1949, the United Nations General Assembly decided to set up the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner / 1950s UNRWA for Refugees (UNHCR), as Suffering and fortitude of young and old in of 1 January 1951, with the Jalazone refugee camp, West Bank principal aim of dealing with refugees in Europe of Palestine refugees, that is, refugees left homeless by World War from the territory that had been under II. -

Becoming PALESTINE

Becoming PALESTINE TOWARD AN ARCHIVAL IMAGINATION OF THE FUTURE GIL Z. HOCHBERG Becoming P ALESTINE GIL Z. HOCHBERG Becoming PALESTINE TOWARD AN ARCHIVAL IMAGINATION OF THE FUTURE © All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Cover designed by Aimee C. Harrison Text designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Portrait Text Regular by Compositor Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Hochberg, Gil Z., [date] author. Title: Becoming Palestine: toward an archival imagination of the future / Gil Z. Hochberg. Description: Durham: Duke University Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identi«ers: ¬¬ 2021005977 (print) ¬¬ 2021005978 (ebook) ´ 9781478013884 (hardcover) ´ 9781478014829 (paperback) ´ 9781478022138 (ebook) Subjects: ¬ : Visual communication— Political aspects— Palestine. | Archival materials— Palestine. | Ethnomusicology— Palestine. | Arab- Israeli con»ict— Mass media and the con»ict. | Palestine— In motion pictures. | ´¬: / Middle Eastern | / History / Con temporary (1945-) Classi«cation: ¬¬ 95.82. 19 634 2021 (print) | ¬¬ 95.82. 19 (ebook) | ¬ 302.2095694— dc23 ¬ rec ord available at https: // lccn . loc . gov / 2021005977 ¬ ebook rec ord available at https: // lccn . loc . gov / 2021005978 Cover art: Steve Sabella, 38 Days of Re-Collection, 2014. b&w «lm negatives (generated from digital images), printed with b&w photo emulsion spread on paint fragments peeled o¾ Jerusalem’s Old City house walls. The photograph was taken in a Palestinian -

Steve Sabella. Archaeology of the Future

STEVE SABELLA ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE FUTURE STEVE SABELLA ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE FUTURE Verona, Centro Internazionale di Fotografia Scavi Scaligeri 8 OTTOBRE - 16 NOVEMBRE 2014 Il Sindaco | Mayor Visite guidate | Guided Tours Davide D’Agostino Mostra a cura di | Curated by Assessore alla Cultura | The Culture Councillor Karin Adrian von Roques Valentina Ferrazzi Flavio Tosi Giulia Magnabosco Consigliera incaricata alla Cultura Valeria Marchi Counsellor for Cultural Affairs Valeria Nicolis Antonia Pavesi Lorenza Roverato | Catalogo a cura di | Catalog edited by Si ringrazia | Many thanks to Direzione Area Cultura | Culture Department Director Servizio guardiania Gallery Attendants Service Beatrice Benedetti Un ringraziamento particolare a Mauro Fiorese. Gabriele Ren Auser Con lui abbiamo preso parte alla Biennale Coordinamento e organizzazione Servizio Sicurezza/Security Testi di | Texts by di Fotografia FotoFest di Houston in veste Società Servizi Socio Culturali Flavio Tosi di portfolio reviewer. Coordination and Organisation Giusi Pasqualini Antonia Pavesi Grazie a quell’esperienza abbiamo Servizio Civile/Civilian Service Karin Adrian von Roques incontrato Karin e Steve Silvano Campedelli Davide Papetti Steve Sabella Progetto e coordinamento manageriale Nadia Johanne Kabalan Special thanks go to Mauro Fiorese, Tirocinio/Internship Project and Managerial Coordination Alice Malesani Leda Manosur who was with us when we took part Giorgio Gaburro Beatrice Benedetti in the FotoFest Biennial of Photography Logistica mostra | Exhibition Logistics in -

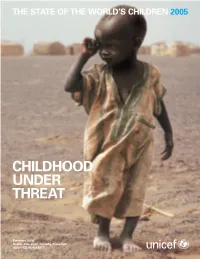

SOWC-2005.Pdf

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2005 CHILDHOOD UNDER THREAT CHILDHOOD I Number of children in the world: 2.2 billion. I Number of children living in developing countries: 1.9 billion. I Number of children living in poverty: 1 billion – every second child. I The under-18 population in Sub-Saharan Africa: 340 million; in Middle East and North Africa: 153 million; in South Asia: 585 million; in East Asia and Pacific: 594 million; in Latin America and Caribbean: 197 million; and in Central and Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CEE/CIS): 108 million. I SHELTER, WATER AND HEALTH CARE I 640 million children in developing countries live without adequate shelter: one in three. I 400 million children have no access to safe water: one in five. I 270 million children have no access to health services: one in seven. I EDUCATION, COMMUNICATION AND INFORMATION I More than 121 million primary- school-age children are out of school; the majority of them are girls. I Number of tele- phones per 100 people in Sweden, 162; in Norway, 158; in South Asia, 4. I Number of Internet users per 100 people in Iceland, 65; in Liechtenstein, 58; in Sweden, 57; in the Republic of Korea and the United States, * 55; in Canada, Denmark, Finland and the Netherlands, 51; and in South Asia, 2. I SURVIVAL I Total number of children younger than five living in France, Germany, Greece and Italy: 10.6 million I Total num- ber of children worldwide who died in 2003 before they were five: 10.6 million. -

Building a Successful Palestinian State

CHILD POLICY This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as CIVIL JUSTICE a public service of the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE 6 INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS NATIONAL SECURITY The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY effective solutions that address the challenges facing SUBSTANCE ABUSE the public and private sectors around the world. TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND monographs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Building a Successful Palestinian State The RAND Palestinian State Study Team Supported by a gift from David and Carol Richards Research for this study was carried out from September 2002 through May 2004 by a multidisciplinary team of RAND researchers, working under the direction of the RAND Health Center for Domestic and International Health Security in conjunction with the Center for Middle East Public Policy (CMEPP), one of RAND’s international programs. -

Colours of Hope Is UNDP

Colours of Hope is UNDP/ PAPP’s Fourth Annual Art Auction and features a collection that covers a diverse group of young male and female artists from across the West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip. The exhibition includes the work of many of Palestine’s most promising up-and- coming artists including Saadeh Radhy, Hani Zo’rob, Basel Magoussi, Nazih Moughrabi and Colours of Mohammed Shanti. The 2005 paintings are reflective of Hope the rich Palestinian artistic an exhibition of Palestinian art and cultural diversity and UNDP/PAPP’s Fourth Annual Art Auction were carefully selected so as to reflect the wealth of talent in the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza. 1 Colours of 2005 Curator: Ehab Shanti Assistant Curator: Dania Darwish and Zoi Constantine HopeH Project Assistant: Murad Bakri an exhibition of Palestinian art Design and Print: Shadi Darwish - Al Nasher Ad. Paintings photography: Steve Sabella UNDP/PAPP’s Fourth Annual Art Auction The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) launched its Programme of Assistance to the Palestinian People (PAPP) in 1978, following the passing of a UN General Assembly resolution in support of the economic and social development of Palestinians. With this objective in mind, UNDP/PAPP has since implemented hundreds of projects throughout the West Bank and Gaza Strip, funded by a number of international donors. Initial funding was provided by UNDP and five bilateral donors: Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands and the United States of America. Since then, UNDP/PAPP has expanded and has now received a total of $600 million from countries around the world. -

Steve SABELLA Fragments 7 MARCH - 10 MAY

63 MARGARET STREET.LONDON.W1W 8SW Steve SABELLA fragments 7 MARCH - 10 MAY Berloni Gallery is proud to present the first UK solo exhibition of Berlin-based Palestinian artist Steve Sabella. From March 7 - May 10, 2014, Cecile Elise Sabella (2008), In Exile (2008), Metamorphosis (2012) and 38 Days of Re-Collection (2014) will be on display. Hubertus Von Amelunxen, writer of Sabella’s upcoming monograph to be published by Hatje Cantz and the Academy of the Arts (Sept 2014), cites how his collages, “form a dazzling tableau of possible transitions and detachment processes between world and image, image and world. Sabella uses photography as an artistic language of existential exile. His relationship with the medium is penetrating.” Sabella came to terms with his exile preferring to remain in transition. As Vilém Flusser writes, “Emigres become free, not when they deny their lost homeland, but when they come to terms with it”. In his works, In Exile, he gives form to the symptoms or side effects of exile, where as in Cecile Elise Sabella, photographs of his daughter’s clothing are stitched to canvas mirroring the duality of exile––a simultaneous presence and absence. But, in Metamorphosis, he confronts the core components that shaped his feeling of alienation. As he writes, “The hard work was finding how to allow for a new transformation, while accepting that my DNA will always stay the same.” It was through the investigation of his state of exile, a process of self-interrogation and introspection, that Sabella was able to dig deeper into the relationship between images and the reality they create. -

The Children of Palestine in the Labour Market

BIRZEIT UNIVERSITY Development Studies Programme The Children of Palestine in the Labour Market (A qualitative participatory study) October 2004 For further information, please write to: Development Studies Programme - Birzeit University UNICEF - Occupied Palestinian Territory P.O.Box 1787, Ramallah P.O Box 25141 Jerusalem Tel: (972-2) 2959250 Tel: (972-2)583-0013/4 Fax: (972-2)2958117 Fax: (972-2) 583-0806 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://home.birzeit.edu/dsp Website: www.unicef.org The viewes expressed in this publication are those of authors and do not necessarily reflect the policies or view of UNICEF, and the designations and presentation of material do not imply any expression of opinion of the United Nations or UNICEF as to the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or the authorities thereof, or as to the delimitation of boundaries or national affiliation. Designed and Printed By: Sky Advertising Co., Ramallah, tel.: ++/972-2-2986878 Photo Credit: UNICEF - occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) / Steve Sabella Development Studies Programme - Birzeit University Table of Contents Work Team 5 Foreword - UNICEF 7 Foreword - DSP 9 Part one: The Present Study 11 First: Introduction 12 Second: Objectives 12 Part Two: Background 15 First Concepts and Laws Related to Child Employment 16 Second An Overview of the Palestinian Context 19 Third: Palestinian Children in the Labour Market 20 Fourth: Conclusions 23 Part Three: Research Methodology 25 First Stage: Preparatory Stage and Research Methodology -

The Journey of Artistic Interrogation and Introspection

Features 199 Steve Sabella The Journey of Artistic Interrogation and Introspection By Yasmine El Rashidi Palestinian-born artist Steve Sabella could well be a different at home, and completely out of place at school. younger, more alternative, more artistic version of the People had a problem with who I was.” late Edward Said. Like the literary exile who lived in an enclave of a world he had created for himself on The result of being born into a culture with this the Upper West Side of Manhattan, surrounded and identity that was formed with perhaps the malfunction consumed and embedded in the construct of texts that of creating difference rather than sameness, was the deconstructed the reality he struggled with, Sabella is foundation for a mind and voice that had scope to one who lives in an equal state of alienation – confined sculpt itself even further in its deviation from the norm. to an exile that transcends place: London, and rather is “Monks go out into the desert, in isolation, to lose contained in the bounds of his mind. A mind that like their identity,” Sabella says. “I decided to lose mine, and Said’s did deconstructs only to rebuild again, but in this become a stranger only to myself.” case, using a terminology of visual narratives. For Sabella the journey has been one of stripping It was perhaps, with him as well, a seed of displacement away the layers of what he was told were himself, and that was placed in the very second he was born. “I love freeing his being from the confines of a set of constructs my name,” Sabella says, “but people had a problem with grouped under headings commonly referred to as it. -

July 2004 Version

Case Studies ADOLESCENT PROGRAMMING EXPERIENCES DURING CONFLICT AND POST-CONFLICT For every child Health, Education, Equality, Protection ADVANCE HUMANITY Adolescent programming experiences during conflict and post-conflict CASE STUDIES United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) June 2004 COVER PHOTO: UNICEF - OPT/2003/STEVE SABELLA A Pyalara/UNICEF sponsored programme with the objective of enhancing self confidence, self expression, cooperation, leadership and skill. Beit Duko West bank, August 2003. Table of Contents ADVANCE COPY 1 Introduction to Case Studies. 3 Acknowledgements 2Broadcasting in Albania: This document was prepared by UNICEF Programme Troç (Straight Talk) . 13 Division, the Office of Emergency Programmes in UNICEF and the UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre with the help and support of UNICEF Country and Regional 3 Peer-to-Peer Counselling on HIV/AIDS Offices. The Women’s Commission for Refugee Women in Angola . 21 and Children also supported the documentation of the participatory case study in northern Uganda. 4 Return to Happiness (Retorno de la Alegria) in Colombia . 29 We would like to express gratitude for the financial sup- 5Young People Participate port provided by the United Kingdom Department for in Peace-Building in Indonesia . 37 International Development (DFID), the United Nations Foundation and the Swedish Internation Development Agency (Sida). 6 Peer-to-Peer Counselling in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT) . 47 7Involvement of Children in the First published in New York by UNITED NATIONS CHILDREN’S FUND (UNICEF) TRC in Sierra Leone . 56 ©UNICEF July 2004 8Youth Education, Development and Participation Programme in Somalia . 65 The designations employed in this publication and the presentation of the material do not imply on the part of the United Nations Children’s Fund the expression of 9 Surviving the War on Adolescents any opinion whatsoever concerning the legal status of in Northern Uganda . -

Colonization of the Imagination

28 Essay Colonization of the Imagination By Steve Sabella Introduction The following essay was written few years ago at a time all watched the Egyptians with anticipation in their when there was a sense of total frustration and defeat eighteen-day fight for their liberation. The real moment in the Arab World. It seemed back then that people of triumph was not when Mubarak left, but when the were entrapped and subjected to a new form of colonial world saw how the Egyptians changed, in a record time, power that did not seek to physically occupy the ‘space’ through their peaceful demonstrations, the distorted and people, but rather it aimed at conquering their image that the ‘system’ had generated for them. It was image, leading in effect to a New World Order. In other a fight for their visual liberation. They managed to defy words, what we were witnessing was the conquering the system and force the world to look at them with and the colonization of the imagination. This, in my different eyes. This essay has two parts, the first dealing opinion, subjects people to a severe mental and physical with image/photo theory and the second with how this paralysis that restricts development and obliterates all theory influences our daily lives to the extent that one notions of personal freedom. Having lived in occupied needs to be aware of it to live in today’s world. Jerusalem for the largest part of my life, I suffered from this colonization to the extent that I needed to uproot Part 1 – God, Art and Walter Benjamin myself in order to re-conquer my imagination, until At the Basilica of the Resurrection in the heart of the Old I reached my states of Euphoria (2010) and Beyond City of occupied Jerusalem – a few hundred meters from Euphoria (2011). -

Kuwait Press Release Draft

Contact: Steve Sabella [email protected] +49 176 61646390 stevesabella.com theparachuteparadox.com September 21, 2016 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE KUWAIT LAUNCH OF INTERNATIONALLY EXHIBITED ARTIST FROM PALESTINE STEVE SABELLA’S BOOK THE PARACHUTE PARADOX The memoir tackles Israeli-occupation, exile, and the Arab World’s fight for liberation. Over his lifetime, Sabella finds that the only way out is to find freedom from the colonisation of the imagination Steve Sabella will launch the English-language, limited edition of his memoir at Contemporary Art Platform (CAP) Kuwait (Shuwaikh Industrial 2, Kuwait), on October 5, 2016 at 7 - 9 pm, with a reading in English (Arabic translation will be available), Arabic discussion with author and literary critic Mohammad Al-As’ad, Q&A and book signing. The occupation of Palestine attaches each Palestinian to an Israeli, as if in a tandem jump. The Israeli is always in control, placing the Palestinian under threat, in a never-ending hostage situa- tion. Born in Jerusalem’s Old City, Steve Sabella found himself with two options: either surrender to this impossible reality, or unbuckle his harness and take a leap of faith. Exploring love and loss, it traces one man’s arduous search for liberation from within, through a confrontation with his colonized imagination. “For many years my life was held hostage by Israeli occupation, but in my dreams I was free. Once I learned how to change my own consciousness, my dreams became my reality. I was born under Israeli occupation but found a way to live free.” Sabella’s memoir travels from the Old City to London, Dubai, and Berlin, interweaving reflections on art and life, and his pursuit of global citizenship.