Becoming PALESTINE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The United Nations and Palestinian Refugees the United Nations and Palestinian Refugees

UNRWA CONTACTS: Public Information Office Gaza HQ P.O. Box 140157 Amman, Jordan 11814 Tel.: +972 8 677 7527 Fax: +972 8 677 7697 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.unrwa.org UNHCR CONTACTS: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees 94, Rue de Montbrillant Case Postale 2500 CH-1211 Genève 2 Dépôt Switzerland Tel.: +41 22 739 8111 Fax: +41 22 739 7334 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.unhcr.org Front cover: Palestinians fleeing to Jordan,June 1967 / UNRWA Back cover: Tents had just been replaced by cement block houses at Khan Younis refugee camp, Gaza Strip, 1955 / UNRWA Inside cover: Baqa’a refugee camp, Jordan, 1969 / UNRWA Opposite: A Palestine refugee with her grandson in Beach refugee camp, Gaza Strip / UNRWA All UNRWA photographs courtesy of UNRWA Photo Archive & Steve Sabella January 2007 2 The United Nations and Palestinian Refugees The United Nations and Palestinian Refugees n December 1949, the United Nations General IAssembly established the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) to provide humanitarian relief to the more than 700,000 refugees and displaced persons who had been forced to flee their homes in Palestine as a result of the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. Also in December 1949, the United Nations General Assembly decided to set up the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner / 1950s UNRWA for Refugees (UNHCR), as Suffering and fortitude of young and old in of 1 January 1951, with the Jalazone refugee camp, West Bank principal aim of dealing with refugees in Europe of Palestine refugees, that is, refugees left homeless by World War from the territory that had been under II. -

Steve Sabella. Archaeology of the Future

STEVE SABELLA ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE FUTURE STEVE SABELLA ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE FUTURE Verona, Centro Internazionale di Fotografia Scavi Scaligeri 8 OTTOBRE - 16 NOVEMBRE 2014 Il Sindaco | Mayor Visite guidate | Guided Tours Davide D’Agostino Mostra a cura di | Curated by Assessore alla Cultura | The Culture Councillor Karin Adrian von Roques Valentina Ferrazzi Flavio Tosi Giulia Magnabosco Consigliera incaricata alla Cultura Valeria Marchi Counsellor for Cultural Affairs Valeria Nicolis Antonia Pavesi Lorenza Roverato | Catalogo a cura di | Catalog edited by Si ringrazia | Many thanks to Direzione Area Cultura | Culture Department Director Servizio guardiania Gallery Attendants Service Beatrice Benedetti Un ringraziamento particolare a Mauro Fiorese. Gabriele Ren Auser Con lui abbiamo preso parte alla Biennale Coordinamento e organizzazione Servizio Sicurezza/Security Testi di | Texts by di Fotografia FotoFest di Houston in veste Società Servizi Socio Culturali Flavio Tosi di portfolio reviewer. Coordination and Organisation Giusi Pasqualini Antonia Pavesi Grazie a quell’esperienza abbiamo Servizio Civile/Civilian Service Karin Adrian von Roques incontrato Karin e Steve Silvano Campedelli Davide Papetti Steve Sabella Progetto e coordinamento manageriale Nadia Johanne Kabalan Special thanks go to Mauro Fiorese, Tirocinio/Internship Project and Managerial Coordination Alice Malesani Leda Manosur who was with us when we took part Giorgio Gaburro Beatrice Benedetti in the FotoFest Biennial of Photography Logistica mostra | Exhibition Logistics in -

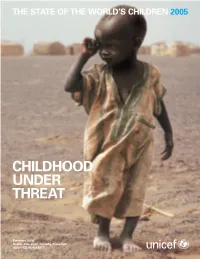

SOWC-2005.Pdf

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2005 CHILDHOOD UNDER THREAT CHILDHOOD I Number of children in the world: 2.2 billion. I Number of children living in developing countries: 1.9 billion. I Number of children living in poverty: 1 billion – every second child. I The under-18 population in Sub-Saharan Africa: 340 million; in Middle East and North Africa: 153 million; in South Asia: 585 million; in East Asia and Pacific: 594 million; in Latin America and Caribbean: 197 million; and in Central and Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CEE/CIS): 108 million. I SHELTER, WATER AND HEALTH CARE I 640 million children in developing countries live without adequate shelter: one in three. I 400 million children have no access to safe water: one in five. I 270 million children have no access to health services: one in seven. I EDUCATION, COMMUNICATION AND INFORMATION I More than 121 million primary- school-age children are out of school; the majority of them are girls. I Number of tele- phones per 100 people in Sweden, 162; in Norway, 158; in South Asia, 4. I Number of Internet users per 100 people in Iceland, 65; in Liechtenstein, 58; in Sweden, 57; in the Republic of Korea and the United States, * 55; in Canada, Denmark, Finland and the Netherlands, 51; and in South Asia, 2. I SURVIVAL I Total number of children younger than five living in France, Germany, Greece and Italy: 10.6 million I Total num- ber of children worldwide who died in 2003 before they were five: 10.6 million. -

Songs of the Jews on the Island of Djerba, Tunisia R

Songs of the Jews on the Island of Djerba, Tunisia R. Davis In 1978, I spent three months in the village of Hara Kebira on the island of Djerba, just off Tunisia's southeastern coastline. I was a graduate student in ethnomusicology at the University of Amsterdam, and my supervisor, dr. Leo Plenckers, had arranged for me to join a fieldwork training programme organised by the Free University of Amsterdam in collaboration with the Tunisian government. Hara Kebira just happened to be one of several loca- tions where a research agreement had been negotiated between the Free University and the local authorities. Djerba is said to be the land of the lotus-eaters in Homer's Odyssey, and its paradisic reputation in myth has some reflection in reality. Its fertile terrain is inhabited by a Berder majority belonging to the Kharajite Moslem sect, Arabs, black Africans, and an ancient Jewish community whose legendary origins date back to the first diaspora, i.e. the exile following the destruction of the first Jeruslem Temple in 586 BCE. Until the radical social and political upheavals of recent decades, these disparate peoples lived together peacefully and relatively prosperously, in an economy based on fishing, farming, various forms of craft (e.g. weaving and pottery making among the Moslems; jewellery making among the Jews) and trade. The Jews are concentrated in two villages: Hara Kebira (big Jewish quarter) lies on the outskirts of Houmt Souk, the island's main port and market town, while Hara Sghira (little Jewish quarter) nestles among olive groves in the open countryside, some seven kilometers inland. -

Building a Successful Palestinian State

CHILD POLICY This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as CIVIL JUSTICE a public service of the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE 6 INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS NATIONAL SECURITY The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY effective solutions that address the challenges facing SUBSTANCE ABUSE the public and private sectors around the world. TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND monographs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Building a Successful Palestinian State The RAND Palestinian State Study Team Supported by a gift from David and Carol Richards Research for this study was carried out from September 2002 through May 2004 by a multidisciplinary team of RAND researchers, working under the direction of the RAND Health Center for Domestic and International Health Security in conjunction with the Center for Middle East Public Policy (CMEPP), one of RAND’s international programs. -

The Palestine Israel Journal

Culture The Parachute Paradox (Chapter from a Jerusalem memoir) Steve Sabella Steve Sabella, born 1975 in Jerusalem, Palestine, is a Berlin-based artist whose work is exhibited and held in collections around the world. He holds a MA in photographic studies from the University of Westminster and a MA in art business from Sotheby’s Institute of Art. He received the 2008 Ellen Auerbach Award from the Akademie der Künste Berlin, which included the subsequent publication of his monograph Steve Sabella— Photography 1997–2014, spanning his two decade career. This is an excerpt from chapter fourteen of The Parachute Paradox. In September 2016 Kerber Verlag published the Berlin-based artist’s memoir, which explores three decades of his life under Israeli occupation and the arduous search for liberation from within. …A year earlier I had rented the occupied house in Ein Karim, Jerusalem, that once belonged to a Palestinian family who in all likelihood had been forced into a refugee camp and then condemned to a lifetime of exile following Israel’s creation in 1948. For those thirty-eight days I struggled with my identity, the Palestinian Right of Return, and morality. I would often think about what Najwan [Darwish] said in the 2007 documentary Jerusalem in Exile, I can’t understand how a nation can take the land of another. Who could live in someone else’s home, without a problem, not even on a psychological level? Isn’t it surprising that the people who live in these houses don’t think about who used to live there? When I took my first step onto the arabesque tiled floor, I felt it shatter under my feet. -

Ethnomusicology and Political Ideology in Mandatory Palestine: Robert Lachmann's “Oriental Music” Projects

Ethnomusicology and Political Ideology in Mandatory Palestine: Robert Lachmann’s “Oriental Music” Projects RUTH F. DAVIS In no other country, perhaps, the need for a sound understanding of [Eastern music] and the opportunity of studying it answer each other so well as they do in Palestine. For the European, here, it is of vital interest to know the mind of his Oriental neighbour; well, music and singing, as being the most spontaneous outcome of it, will be his surest guide provided he listens to it with sympathy instead of disdain. Robert Lachmann (Palestine Broadcasting Station, 18 November, 1936) Thus Robert Lachmann, a comparative musicologist from Berlin, addressed his European listeners in the first of his series of twelve radio programs entitled “Oriental Music”, broadcast on the English language program of the Palestine Broadcasting Service (PBS) between 18 November 1936 and 28 April 1937. 1 Focusing on sacred and secular musical traditions of different “Oriental” communities living in and around Jerusalem, including Bedouin and Palestinian Arabs, Yemenite, Kurdish and Baghdadi Jews, Copts and Samaritans, Lachmann’s lectures were illustrated by more than thirty musical examples performed live in the studio by local musicians and singers and simultaneously recorded on metal disc. In two lectures (nos 10 and 11), based on commercial recordings, he contextualized the live performances with wide- ranging surveys of the urban musical traditions of North Africa and the Middle East, extending beyond the Arab world to Turkey, Persia, and Hindustan. 2 I was introduced to Lachmann’s radio programs by his nephew Professor Sir Peter Lachmann, Fellow of Christ’s College, University of Cambridge, who kindly gave me copies of his uncle’s lectures; the first was written in Lachmann’s hand, the rest were typed. -

Colours of Hope Is UNDP

Colours of Hope is UNDP/ PAPP’s Fourth Annual Art Auction and features a collection that covers a diverse group of young male and female artists from across the West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip. The exhibition includes the work of many of Palestine’s most promising up-and- coming artists including Saadeh Radhy, Hani Zo’rob, Basel Magoussi, Nazih Moughrabi and Colours of Mohammed Shanti. The 2005 paintings are reflective of Hope the rich Palestinian artistic an exhibition of Palestinian art and cultural diversity and UNDP/PAPP’s Fourth Annual Art Auction were carefully selected so as to reflect the wealth of talent in the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza. 1 Colours of 2005 Curator: Ehab Shanti Assistant Curator: Dania Darwish and Zoi Constantine HopeH Project Assistant: Murad Bakri an exhibition of Palestinian art Design and Print: Shadi Darwish - Al Nasher Ad. Paintings photography: Steve Sabella UNDP/PAPP’s Fourth Annual Art Auction The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) launched its Programme of Assistance to the Palestinian People (PAPP) in 1978, following the passing of a UN General Assembly resolution in support of the economic and social development of Palestinians. With this objective in mind, UNDP/PAPP has since implemented hundreds of projects throughout the West Bank and Gaza Strip, funded by a number of international donors. Initial funding was provided by UNDP and five bilateral donors: Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands and the United States of America. Since then, UNDP/PAPP has expanded and has now received a total of $600 million from countries around the world. -

Steve SABELLA Fragments 7 MARCH - 10 MAY

63 MARGARET STREET.LONDON.W1W 8SW Steve SABELLA fragments 7 MARCH - 10 MAY Berloni Gallery is proud to present the first UK solo exhibition of Berlin-based Palestinian artist Steve Sabella. From March 7 - May 10, 2014, Cecile Elise Sabella (2008), In Exile (2008), Metamorphosis (2012) and 38 Days of Re-Collection (2014) will be on display. Hubertus Von Amelunxen, writer of Sabella’s upcoming monograph to be published by Hatje Cantz and the Academy of the Arts (Sept 2014), cites how his collages, “form a dazzling tableau of possible transitions and detachment processes between world and image, image and world. Sabella uses photography as an artistic language of existential exile. His relationship with the medium is penetrating.” Sabella came to terms with his exile preferring to remain in transition. As Vilém Flusser writes, “Emigres become free, not when they deny their lost homeland, but when they come to terms with it”. In his works, In Exile, he gives form to the symptoms or side effects of exile, where as in Cecile Elise Sabella, photographs of his daughter’s clothing are stitched to canvas mirroring the duality of exile––a simultaneous presence and absence. But, in Metamorphosis, he confronts the core components that shaped his feeling of alienation. As he writes, “The hard work was finding how to allow for a new transformation, while accepting that my DNA will always stay the same.” It was through the investigation of his state of exile, a process of self-interrogation and introspection, that Sabella was able to dig deeper into the relationship between images and the reality they create. -

Global Musicology Beyond Globalization

1 29th Annual(2018) Koizumi Fumio Prize PRIZE LECTURE (FULL TEXT) ◆NOT FOR CITATION◆ “For This Purpose I Wish To Collect Data about the History of Every Historical Moment”: Global Musicology beyond Globalization Philip V. Bohlman (Ludwig Rosenberger Distinguished Service Professor in Jewish History, Department of Music and the College, The University of Chicago; Honorarprofessor, Hochschule fur Musik, Theater und Medien Hannover) The Musical Encounter and the Historical Moment In May 1769 – precisely 249 years ago – the twenty-five-year-old theologian, anthropologist, philosopher, and music scholar, Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803) embarked on a sea journey that would take him far from his Baltic home in Riga, Latvia, and across the great seas of human experience before he would find his way to Germany, where he would produce a lifetime of thought that, among other influences, would transform the understanding of what music in the world was and could be. Herder kept a journal, actually elaborate field notes, on his sea journey, in which he intimately traced the transformation of personal encounter to the global experience of a common humanity (see Herder 1997). In his notes, which he himself never published, he made the challenge he was embracing as a scholar indebted to a global human community explicit: For this purpose I wish to collect data about the history of every historical moment, each evoking a picture of its own use, function, custom, burdens, and pleasures. Accordingly, I shall assemble everything I can, leading up to the present day, in order to put it to good use. (cited in Herder and Bohlman 2017, 266) Herder’s moment of global encounter quickly and sweepingly left its impact on music, for among the data he collected were the songs of peoples throughout the world. -

The Children of Palestine in the Labour Market

BIRZEIT UNIVERSITY Development Studies Programme The Children of Palestine in the Labour Market (A qualitative participatory study) October 2004 For further information, please write to: Development Studies Programme - Birzeit University UNICEF - Occupied Palestinian Territory P.O.Box 1787, Ramallah P.O Box 25141 Jerusalem Tel: (972-2) 2959250 Tel: (972-2)583-0013/4 Fax: (972-2)2958117 Fax: (972-2) 583-0806 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://home.birzeit.edu/dsp Website: www.unicef.org The viewes expressed in this publication are those of authors and do not necessarily reflect the policies or view of UNICEF, and the designations and presentation of material do not imply any expression of opinion of the United Nations or UNICEF as to the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or the authorities thereof, or as to the delimitation of boundaries or national affiliation. Designed and Printed By: Sky Advertising Co., Ramallah, tel.: ++/972-2-2986878 Photo Credit: UNICEF - occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) / Steve Sabella Development Studies Programme - Birzeit University Table of Contents Work Team 5 Foreword - UNICEF 7 Foreword - DSP 9 Part one: The Present Study 11 First: Introduction 12 Second: Objectives 12 Part Two: Background 15 First Concepts and Laws Related to Child Employment 16 Second An Overview of the Palestinian Context 19 Third: Palestinian Children in the Labour Market 20 Fourth: Conclusions 23 Part Three: Research Methodology 25 First Stage: Preparatory Stage and Research Methodology -

The Journey of Artistic Interrogation and Introspection

Features 199 Steve Sabella The Journey of Artistic Interrogation and Introspection By Yasmine El Rashidi Palestinian-born artist Steve Sabella could well be a different at home, and completely out of place at school. younger, more alternative, more artistic version of the People had a problem with who I was.” late Edward Said. Like the literary exile who lived in an enclave of a world he had created for himself on The result of being born into a culture with this the Upper West Side of Manhattan, surrounded and identity that was formed with perhaps the malfunction consumed and embedded in the construct of texts that of creating difference rather than sameness, was the deconstructed the reality he struggled with, Sabella is foundation for a mind and voice that had scope to one who lives in an equal state of alienation – confined sculpt itself even further in its deviation from the norm. to an exile that transcends place: London, and rather is “Monks go out into the desert, in isolation, to lose contained in the bounds of his mind. A mind that like their identity,” Sabella says. “I decided to lose mine, and Said’s did deconstructs only to rebuild again, but in this become a stranger only to myself.” case, using a terminology of visual narratives. For Sabella the journey has been one of stripping It was perhaps, with him as well, a seed of displacement away the layers of what he was told were himself, and that was placed in the very second he was born. “I love freeing his being from the confines of a set of constructs my name,” Sabella says, “but people had a problem with grouped under headings commonly referred to as it.