BURNOUT and the NEW FINNISH ECONOMY a Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Personal Agency at the Swedish Age of Greatness 1560–1720

Edited by Petri Karonen and Marko Hakanen Marko and Karonen Petri by Edited Personal Agency at the Swedish Age of Greatness 1560-1720 provides fresh insights into the state-building process in Sweden. During this transitional period, many far-reaching administrative reforms were the Swedish at Agency Personal Age of Greatness 1560–1720 Greatness of Age carried out, and the Swedish state developed into a prime example of the ‘power-state’. Personal Agency In early modern studies, agency has long remained in the shadow of the study of structures and institutions. State building in Sweden at the Swedish Age of was a more diversified and personalized process than has previously been assumed. Numerous individuals were also important actors Greatness 1560–1720 in the process, and that development itself was not straightforward progression at the macro-level but was intertwined with lower-level Edited by actors. Petri Karonen and Marko Hakanen Editors of the anthology are Dr. Petri Karonen, Professor of Finnish history at the University of Jyväskylä and Dr. Marko Hakanen, Research Fellow of Finnish History at the University of Jyväskylä. studia fennica historica 23 isbn 978-952-222-882-6 93 9789522228826 www.finlit.fi/kirjat Studia Fennica studia fennica anthropologica ethnologica folkloristica historica linguistica litteraria Historica The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. -

Pekka Ahtiainen Ja Jukka Tervonen MENNEISYYDEN TUTKIJAT JA METODIEN VARTIJAT KÄSIKIRJOJA 17:1 Pekka Ahtiainen Ja Jukka Tervonen

Pekka Ahtiainen ja Jukka Tervonen MENNEISYYDEN TUTKIJAT JA METODIEN VARTIJAT KÄSIKIRJOJA 17:1 Pekka Ahtiainen ja Jukka Tervonen Menneisyyden tutkijat ja metodfen vartijat Matka suomalaiseen historiankirjoitukseen Luvun Linjoilla ja linjojen takana kirjoittanut Ilkka Herlin Suomen Historiallinen Seura Helsinki 1996 Kansikuva: Maantieteellisiä kuvia n:o 21: Suomen Pankki, Valtionarkisto ja Säätytalo. Kansanopettajain O.Y. Valistus. Museovirasto © Pekka Ahtiainen ja Jukka Tervonen ISSN 0081-9417 ISBN 951-710-039-6 Vammalan Kirjapaino Oy 1996 S aatteeksi Nyt käsillä oleva kirja on syntynyt Päiviö Tommilan johtamassa ja Suo- men Akatemian kulttuurin ja yhteiskunnan tutkimuksen toimikunnan rahoittamassa projektissa Historioitsija ja yhteiskunta. Tutkimus ja tutkijan rooli 1800-luvun lopun ja 1900-luvun Suomessa. Aihepiiriltään ja käsittelytavaltaan kirja liittyy luontevasti projektin vuonna 1994 ilmesty- neeseen kokoomateokseen Historia, sosiologia ja Suomi. Niinikään tutkimus niveltyy kiinteästi projektin muiden jäsenten laatimaan, piakkoin valmistuvaan työhön Historiantutkijan muotokuva. Tällainen tutkimus ei tietysti synny vain kirjastojen kätköissä, tutki- joiden omissa tieteelle pyhitetyissä skiitoissa eikä kirjoittajien yhteisessä aivoriihessä. Tahdommekin muistaa lämpimästi henkilöitä, jotka ovat lukeneet käsikirjoituksemme eri versioita ja auttaneet tekijöitä ideoiden kehittelyssä. Etenkin projektimme muut jäsenet, Päiviö Tommila, John Strömberg, Henrik Meinander ja Ilkka Herlin ovat pakottaneet kirjoittajat miettimään monet asiat uusiksi -

The Multicultural Moment

Mats Wickström View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE The Multicultural provided by National Library of Finland DSpace Services Moment The History of the Idea and Politics of Multiculturalism in Sweden in Comparative, Transnational and Biographical Context, Mats Wickström 1964–1975 Mats Wickström | The Multicultural Moment | 2015 | Wickström Mats The studies in this compilation thesis examine the origins The Multicultural Moment and early post-war history of the idea of multiculturalism as well as the interplay between idea and politics in The History of the Idea and Politics of Multiculturalism in Sweden in the shift from a public ideal of homogeneity to an ideal Comparative, Transnational and Biographical Context, 1964–1975 of multiculturalism in Sweden. The thesis shows that ethnic activists, experts and offi cials were instrumental in the establishment of multiculturalism in Sweden, as they also were in two other early adopters of multiculturalism, Canada and Australia. The breakthrough of multiculturalism, such as it was within the limits of the social democratic welfare-state, was facilitated by who the advocates were, for whom they made their claims, the way the idea of multiculturalism was conceptualised and legitimised as well as the migratory context. 9 789521 231339 ISBN 978-952-12-3133-9 Mats Wikstrom B5 Kansi s16 Inver260 9 December 2014 2:21 PM THE MULTICULTURAL MOMENT © Mats Wickström 2015 Cover picture by Mats Wickström & Frey Wickström Author’s address: History Dept. of Åbo Akademi -

What Is Neo-Liberalism? Justifications of Deregulating Financial Markets in Norway and Finland © SIFO 2015 Project Note No 6 – 2015

Project note no 6-2015 Pekka Sulkunen What is Neo-liberalism? Justifications of deregulating financial markets in Norway and Finland © SIFO 2015 Project Note no 6 – 2015 NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR CONSUMER RESEARCH Sandakerveien 24 C, Building B P.O. Box 4682 Nydalen N-0405 Oslo www.sifo.no Due to copyright restrictions, this report is not to be copied from or distributed for any purpose without a special agreement with SIFO. Reports made available on the www.sifo.no site are for personal use only. Copyright infringement will lead to a claim for compensation. Prosjektrapport nr.6 - 2015 Tittel Antall sider Dato 48 27.10.2015 Title ISBN ISSN What is Neo-liberalism? Justifications of deregulating financial markets in Norway and Finland Forfatter(e) Prosjektnummer Faglig ansvarlig sign. Pekka Sulkunen 11201014 Oppdragsgiver Norges Forskningsråd Sammendrag Rapporten dokumenter at dereguleringen av den norske og finske økonomien først og fremst handlet om politikk og politiske prosesser, og i liten grad begrunnet i økonomisk teori. Heller ikke neoliberal filosofi slik vi kjenner den fra USA og Storbritannia spilte noen stor rolle i de to landene. Isteden handlet det om forestillingen om, og fremveksten av, en ny type velferdsstat med behov for en moralsk legitimering av autonomi. Summary The report documents that the deregulation of the Norwegian and Finnish economy primarily was about politics and political processes, and to a much lesser extent about justifications rooted in economic theory. Nor neoliberal philosophy as we know it from the US and Britain played a major role in the two countries. Instead, it was about the notion, and the emergence of, a new kind of welfare state in need of a moral legitimization of autonomy. -

The Danish-German Border: Making a Border and Marking Different Approaches to Minority Geographical Names Questions

The Danish-German border: Making a border and marking different approaches to minority geographical names questions Peter GAMMELTOFT* The current German-Danish border was established in 1920-21 following a referendum, dividing the original duchy of Schleswig according to national adherence. This border was thus the first border, whose course was decided by the people living on either side of it. Nonetheless, there are national and linguistic minorities on either side of the border even today – about 50,000 Danes south of the border and some 20,000 Germans north of the border. Although both minorities, through the European Union’s Charter for Regional and National Minorities, have the right to have signposting and place-names in their own language, both minorities have chosen not to demand this. Elsewhere in the German- Scandinavian region, minorities have claimed this right. What is the reason behind the Danish and German minorities not having opted for onomastic equality? And how does the situation differ from other minority naming cases in this region? These questions, and some observations on how the minorities on the German-Danish border may be on their way to obtaining onomastic equality, will be discussed in this paper. INTRODUCTION Article 10.2.g. of the Council of Europe’s European Charter for Regional and National Minorities (ETS no. 148) calls for the possibility of public display of minority language place-names.1 This is in accordance with the Council of Europe’s Convention no. 157: Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities. Here, the right for national minorities to use place-names is expressed in Article 11, in particular sub-article 3,2 which allows for the possibility of public display of traditional minority language * Professor, University of Copenhagen, Denmark. -

Finnish Studies

Journal of Finnish Studies Volume 23 Number 1 November 2019 ISSN 1206-6516 ISBN 978-1-7328298-1-7 JOURNAL OF FINNISH STUDIES EDITORIAL AND BUSINESS OFFICE Journal of Finnish Studies, Department of English, 1901 University Avenue, Evans 458, Box 2146, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, TEXAS 77341-2146, USA Tel. 1.936.294.1420; Fax 1.936.294.1408 E-mail: [email protected] EDITORIAL STAFF Helena Halmari, Editor-in-Chief, Sam Houston State University [email protected] Hanna Snellman, Co-Editor, University of Helsinki [email protected] Scott Kaukonen, Assoc. Editor, Sam Houston State University [email protected] Hilary-Joy Virtanen, Asst. Editor, Finlandia University [email protected] Sheila Embleton, Book Review Editor, York University [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Börje Vähämäki, Founding Editor, JoFS, Professor Emeritus, University of Toronto Raimo Anttila, Professor Emeritus, University of California, Los Angeles Michael Branch, Professor Emeritus, University of London Thomas DuBois, Professor, University of Wisconsin, Madison Sheila Embleton, Distinguished Research Professor, York University Aili Flint, Emerita Senior Lecturer, Associate Research Scholar, Columbia University Tim Frandy, Assistant Professor, Western Kentucky University Daniel Grimley, Professor, Oxford University Titus Hjelm, Associate Professor, University of Helsinki Daniel Karvonen, Senior Lecturer, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Johanna Laakso, Professor, University of Vienna Jason Lavery, Professor, Oklahoma State University James P. Leary, Professor Emeritus, University of Wisconsin, Madison Andrew Nestingen, Associate Professor, University of Washington, Seattle Jyrki Nummi, Professor, University of Helsinki Jussi Nuorteva, Director General, The National Archives of Finland Juha Pentikäinen, Professor, University of Lapland Oiva Saarinen, Professor Emeritus, Laurentian University, Sudbury Beth L. -

Transnational Finnish Mobilities: Proceedings of Finnforum XI

Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen (Eds.) Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen This volume is based on a selection of papers presented at Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen (Eds.) the conference FinnForum XI: Transnational Finnish Mobili- ties, held in Turku, Finland, in 2016. The twelve chapters dis- cuss two key issues of our time, mobility and transnational- ism, from the perspective of Finnish migration. The volume is divided into four sections. Part I, Mobile Pasts, Finland and Beyond, brings forth how Finland’s past – often imagined TRANSNATIONAL as more sedentary than today’s mobile world – was molded by various short and long-distance mobilities that occurred FINNISH MOBILITIES: both voluntarily and involuntarily. In Part II, Transnational Influences across the Atlantic, the focus is on sociocultural PROCEEDINGS OF transnationalism of Finnish migrants in the early 20th cen- tury United States. Taken together, Parts I and II show how FINNFORUM XI mobility and transnationalism are not unique features of our FINNISH MOBILITIES TRANSNATIONAL time, as scholars tend to portray them. Even before modern communication technologies and modes of transportation, migrants moved back and forth and nurtured transnational ties in various ways. Part III, Making of Contemporary Finn- ish America, examines how Finnishness is understood and maintained in North America today, focusing on the con- cepts of symbolic ethnicity and virtual villages. Part IV, Con- temporary Finnish Mobilities, centers on Finns’ present-day emigration patterns, repatriation experiences, and citizen- ship practices, illustrating how, globally speaking, Finns are privileged in their ability to be mobile and exercise transna- tionalism. Not only is the ability to move spread very uneven- ly, so is the capability to upkeep transnational connections, be they sociocultural, economic, political, or purely symbol- ic. -

The Transformation of an Oral Poem in Elias Lönnrot's Kalevala

Oral Tradition, 8/2 (1993): 247-288 From Maria to Marjatta: The Transformation of an Oral Poem in Elias Lönnrot’s Kalevala1 Thomas DuBois The question of Elias Lönnrot’s role in shaping the texts that became his Kalevala has stirred such frequent and vehement debate in international folkloristic circles that even persons with only a passing interest in the subject of Finnish folklore have been drawn to the question. Perhaps the notion of academic fraud in particular intrigues those of us engaged in the profession of scholarship.2 And although anyone who studies Lönnrot’s life and endeavors will discover a man of utmost integrity, it remains difficult to reconcile the extensiveness of Lönnrot’s textual emendations with his stated desire to recover and present the ancient epic traditions of the Finnish people. In part, the enormity of Lönnrot’s project contributes to the failure of scholars writing for an international audience to pursue any analysis beyond broad generalizations about the author’s methods of compilation, 1 Research for this study was funded in part by a grant from the Graduate School Research Fund of the University of Washington, Seattle. 2 Comparetti (1898) made it clear in this early study of Finnish folk poetry that the Kalevala bore only partial resemblance to its source poems, a fact that had become widely acknowledged within Finnish folkoristic circles by that time. The nationalist interests of Lönnrot were examined by a number of international scholars during the following century, although Lönnrot’s fairly conservative views on Finnish nationalism became equated at times with the more strident tone of the turn of the century, when the Kalevala was made an inspiration and catalyst for political change (Mead 1962; Wilson 1976; Cocchiara 1981:268-70; Turunen 1982). -

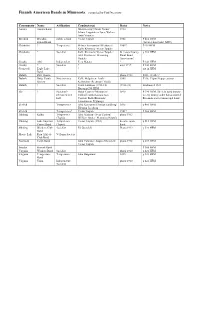

Finnish American Bands in Minnesota, Compiled by Paul Niemisto

Finnish American Bands in Minnesota, compiled by Paul Niemisto Community Name Affiliation Conductor(s) Dates Notes Aurora Aurora Band Miettinen(sp?)/Matti Niemi/ 1910 Jalmar Laupiainen/ Isaac Walma/ Antti Viitanen. Biwabik Biwabik public school Victor Taipale 1902 P 482 HFM School Band (1st in school band MN?) Chisholm ? Temperence Helmer hermanson/ Miettunen/ 1904? P494 HFM Kalle Kleimola/ Victor Taipale Chisholm ? Socialist Kalle Kleimola/ Victor Taipale/ St Louis County p 498 HFM Alex Koivunen/ Hemming Rural Band Hautala Association? Crosby Ahti Independent Eero Matara ? P 141 HFM Crosby ? Socialist ? after 1917 P 141 HFM Cromwell Eagle Lake ? not in HFM Band Duluth SSO Osasto photo 1913 P243, cl+trb+7 Duluth Nuija Youth Nuorisoseura Kalle Holpainen/ Louhi/ 1905 P246, Viipuri/Lappeenranta Society Kellosalmi/ Beckman/ Yrjölä Duluth ? Socialist Frank Lindroos (1913-18) (1913-18) Lindroos d 1923 Bio on p 298 HFM Ely ? Socialist?- Oskar Castren/ Miettunen/ 1890 P 390 HFM, The Ely band history rehearsed in S Farihoff/ Erkki Laitala/Jack is very murky/ other bands started/ hall Castren/ Kalle Kleimola/ Kleemols started municipal band Liimatainen/ Pyylampi Eveleth Termperence Alex Koivunen/ Herman Lindberg/ 1895 p 466 HFM Filemon Jacobson Eveleth Termperence? Victor Taipale 1901? P 466 HFM Hibbing Kaiku Temperence Alex Mattson/ Oscar Castren/ photo 1913 (Tapio) William Ahola/ Hemming Hautala Hibbing Lake Superior Temperence Victor Taipale (1901) became town p 512 HFM Cornet Band (Tapio) band Hibbing Workers Club Socialist Ed Grondahl Photo 1912 p 521 HFM Band Moose Lake Raju Athletic Vellamo Society Club Band Naswauk Town Band John Colander/ August Miettinen/ photo 1912 p 607 HFM Victor Taipale Soudan Finnish Band P 366 HFM Virginia Workers Band Socialist photo 1910 p 421 HFM Virginia Temperance Temperance John Haapasaari 1895 p 422 HFM Band Virginia Yrinä Independent/ photo 1910 p 422 HFM Socialist . -

Norwegian and Swedish Forest Finn Research

Norwegian and Swedish Forest Finn Research Elaine Hasleton, BA, AG® [email protected] Check Church records to identify your ancestor – parish and farm Look for Finnish family names! Check the Norwegian bygdebøker for possible Finnish names. Utilize Finnskog Reference Books. (See book list). Try to tie into the 1823 time period and Gottlund’s 1823 census book. C.A. Gottlunds Folkmängden på Finnskogarne fra 1823. Once the farm is identified, use the Jarl Ericson books. Skogfinska släktnamn i Skandinavien book by Bladh, Myhrvold, Persson. Useful when you’ve learned your Finnish family names. Use unique sources, such as tax records which are one of the best sources to find genealogical information in Norway, Sweden, and Finland. Take a Family Tree DNA test, as they have a Forest Finn DNA Project. Contact Finnskog experts to check their databases. Coordinate with Elaine at [email protected] DNA steps: Be sure to submit your pedigree to Family Tree DNA Use Family Finder to help determine if it’s likely or not Exceptional books to expand your knowledge about the Forest Finns. The Forest Finns of Scandinavia by Maud Wedin Forest Finn Encounters by Oppenheim, Florence and Daniel Svensson. Give back by sharing your family information. Unique source content: Church records (Kirkebøker) Tax records (Skatteregister) Inventory records (Skifter) Old maps (Gamle karter) Legal records (Juridiska register) Military sources (Militære kilder/Militære ruller) Special unique sources: 1636 Household Exams of Finns in Orsa (Sweden) 1674 Census (Finns in Fryksdalen) (Sweden) 1686 Finnish Census (Norway) 1700 Finnish Census (Swedes and Finns) (Norway) 1706 Finnish Census of Hof parish (Norway) 1716 -17 Household exams Dalby parish (Sweden) C. -

E Bar T Stems We've Raised the Bar for Content Management Systems

Nordic Busi August 2013 N We’veWe’ve raisedraised thethe barbar ess r eport forfor contentcontent managementmanagement systemssystems WithWith competition competition ever ever increasing, increasing, end end users users demands demands continue continue to to rise. rise. We We developed developed a systema system forfor handling handling both both your your image image and and your your customer customer service service – effortlessly,– effortlessly, everywhere. everywhere. OneOne decision decision – One– One ready-made ready-made solution. solution. ALEXANDER WHO STUBB IS THE WEBSITE E-COMMERCE MOBILE FACEBOOK 5 Hints for WEBSITE E-COMMERCE MOBILE FACEBOOK Internationali- GREATEST zation BUSINESS THINKER MALCOLM IN THE GLADWELL NORDICS? Teaching People How to Succeed FOCUS ON CONTENT Sharpen your competitive edge www.webio.fi FOCUS ON CONTENT Sharpen your competitive edge www.webio.fi The Softer Side of Jimmy Are you credible in different media? WAles founder of Wikipedia Are you credible in different media? Page Your presence in different media affects the customers’ perception of your brand. Internet’s Virtual Jack Your presence in different media affects the customers’ perception of your brand. Focusing on graphic design, Semio understands the importance of a consistent image. Create an Impression August 2013 Focusing on graphic design, Semio understands the importance of a consistent image. Create an Impression Tour De Force ? 27 IDEA | EXECUTION | RESULT www.semio.fi IDEA | EXECUTION | RESULT www.semio.fi 64 NORDIC BUSINESS REPORT AUGUST 2013 WelchAUGUST 2013 NORDIC BUSINESS REPORT 1 WHO WILL BE THE NEXT FEEDBACK FROM OUR CUSTOMERS: Our real estate agent was ab- TO SAVE solutely lovely! Nothing but good things to say about her. -

A History of Toivola, Michigan by Cynthia Beaudette AALC

A A Karelian Christmas (play) A Place of Hope: A History of Toivola, Michigan By Cynthia Beaudette AALC- Stony Lake Camp, Minnesota AALC- Summer Camps Aalto, Alvar Aapinen, Suomi: College Reference Accordions in the Cutover (field recording album) Adventure Mining Company, Greenland, MI Aged, The Over 80s Aging Ahla, Mervi Aho genealogy Aho, Eric (artist) Aho, Ilma Ruth Aho, Kalevi, composers Aho, William R. Ahola, genealogy Ahola, Sylvester Ahonen Carriage Works (Sue Ahonen), Makinen, Minn. Ahonen Lumber Co., Ironwood, Michigan Ahonen, Derek (playwrite) Ahonen, Tauno Ahtila, Eija- Liisa (filmmaker) Ahtisaan, Martti (politician) Ahtisarri (President of Finland 1994) Ahvenainen, Veikko (Accordionist) AlA- Hiiro, Juho Wallfried (pilot) Ala genealogy Alabama Finns Aland Island, Finland Alanen, Arnold Alanko genealogy Alaska Alatalo genealogy Alava, Eric J. Alcoholism Alku Finnish Home Building Association, New York, N.Y. Allan Line Alston, Michigan Alston-Brighton, Massachusetts Altonen and Bucci Letters Altonen, Chuck Amasa, Michigan American Association for State and Local History, Nashville, TN American Finn Visit American Finnish Tourist Club, Inc. American Flag made by a Finn American Legion, Alfredo Erickson Post No. 186 American Lutheran Publicity Bureau American Pine, Muonio, Finland American Quaker Workers American-Scandinavian Foundation Amerikan Pojat (Finnish Immigrant Brass Band) Amerikan Suomalainen- Muistelee Merikoskea Amerikan Suometar Amerikan Uutiset Amish Ammala genealogy Anderson , John R. genealogy Anderson genealogy