Vol. 12 • No. 2 • 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Personal Agency at the Swedish Age of Greatness 1560–1720

Edited by Petri Karonen and Marko Hakanen Marko and Karonen Petri by Edited Personal Agency at the Swedish Age of Greatness 1560-1720 provides fresh insights into the state-building process in Sweden. During this transitional period, many far-reaching administrative reforms were the Swedish at Agency Personal Age of Greatness 1560–1720 Greatness of Age carried out, and the Swedish state developed into a prime example of the ‘power-state’. Personal Agency In early modern studies, agency has long remained in the shadow of the study of structures and institutions. State building in Sweden at the Swedish Age of was a more diversified and personalized process than has previously been assumed. Numerous individuals were also important actors Greatness 1560–1720 in the process, and that development itself was not straightforward progression at the macro-level but was intertwined with lower-level Edited by actors. Petri Karonen and Marko Hakanen Editors of the anthology are Dr. Petri Karonen, Professor of Finnish history at the University of Jyväskylä and Dr. Marko Hakanen, Research Fellow of Finnish History at the University of Jyväskylä. studia fennica historica 23 isbn 978-952-222-882-6 93 9789522228826 www.finlit.fi/kirjat Studia Fennica studia fennica anthropologica ethnologica folkloristica historica linguistica litteraria Historica The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. -

The Extent of Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Prior to Columbus Donald E

Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 6 | Issue 1 Article 3 August 2016 The Extent of Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Prior to Columbus Donald E. Warden Oglethorpe University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur Part of the Canadian History Commons, European History Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Medieval History Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Warden, Donald E. (2016) "The Extent of Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Prior to Columbus," Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research: Vol. 6 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur/vol6/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Extent of Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Prior to Columbus Cover Page Footnote I would like to thank my honors thesis committee: Dr. Michael Rulison, Dr. Kathleen Peters, and Dr. Nicholas Maher. I would also like to thank my friends and family who have supported me during my time at Oglethorpe. Moreover, I would like to thank my academic advisor, Dr. Karen Schmeichel, and the Director of the Honors Program, Dr. Sarah Terry. I could not have done any of this without you all. This article is available in Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur/vol6/iss1/3 Warden: Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Part I: Piecing Together the Puzzle Recent discoveries utilizing satellite technology from Sarah Parcak; archaeological sites from the 1960s, ancient, fantastical Sagas, and centuries of scholars thereafter each paint a picture of Norse-Indigenous contact and relations in North America prior to the Columbian Exchange. -

The Multicultural Moment

Mats Wickström View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE The Multicultural provided by National Library of Finland DSpace Services Moment The History of the Idea and Politics of Multiculturalism in Sweden in Comparative, Transnational and Biographical Context, Mats Wickström 1964–1975 Mats Wickström | The Multicultural Moment | 2015 | Wickström Mats The studies in this compilation thesis examine the origins The Multicultural Moment and early post-war history of the idea of multiculturalism as well as the interplay between idea and politics in The History of the Idea and Politics of Multiculturalism in Sweden in the shift from a public ideal of homogeneity to an ideal Comparative, Transnational and Biographical Context, 1964–1975 of multiculturalism in Sweden. The thesis shows that ethnic activists, experts and offi cials were instrumental in the establishment of multiculturalism in Sweden, as they also were in two other early adopters of multiculturalism, Canada and Australia. The breakthrough of multiculturalism, such as it was within the limits of the social democratic welfare-state, was facilitated by who the advocates were, for whom they made their claims, the way the idea of multiculturalism was conceptualised and legitimised as well as the migratory context. 9 789521 231339 ISBN 978-952-12-3133-9 Mats Wikstrom B5 Kansi s16 Inver260 9 December 2014 2:21 PM THE MULTICULTURAL MOMENT © Mats Wickström 2015 Cover picture by Mats Wickström & Frey Wickström Author’s address: History Dept. of Åbo Akademi -

October 2017 President's Message by Meshon Rawls “Why Are You Here? More Page

Volume 77, No. 2 Eighth Judicial Circuit Bar Association, Inc. October 2017 President's Message By Meshon Rawls “Why are you here? More page. I am an African-American woman with a colorful importantly, why are each of life story – a story filled with experiences that have us lawyers? Why is not only a prepared me for this very moment. Unfortunately, critical question for each of us; the demands of the profession have a way of why is also a critical question overshadowing the essence of who we are. So, what for the Florida Bar.” These were do we do? I suggest we take heed to the words of the words of Michael Higer, the wisdom shared by Chester Chance, a retired Judge in President of the Florida Bar, as the Eighth Circuit. In his introduction of Charlie Carter, he elaborated on the mission the recipient of the 2016 Tomlinson Award, Judge of the Florida Bar during his Chance spoke of the times when lawyers would get swearing in speech in June. As I together after work. As I listened, I envisioned getting considered his questions, I found myself reassessing to know those who I often see, but never seem to find the mission of the Eighth Judicial Circuit Bar the time to have an in-depth conversation with - to Association (EJCBA). What is our why? The mission hear their stories, to acknowledge their perspective, of the EJCBA is to assist attorneys in the practice to appreciate their similarities and differences. of law and in their service to the judicial system To address this issue, I suggest we take and their clients and their community. -

The Danish-German Border: Making a Border and Marking Different Approaches to Minority Geographical Names Questions

The Danish-German border: Making a border and marking different approaches to minority geographical names questions Peter GAMMELTOFT* The current German-Danish border was established in 1920-21 following a referendum, dividing the original duchy of Schleswig according to national adherence. This border was thus the first border, whose course was decided by the people living on either side of it. Nonetheless, there are national and linguistic minorities on either side of the border even today – about 50,000 Danes south of the border and some 20,000 Germans north of the border. Although both minorities, through the European Union’s Charter for Regional and National Minorities, have the right to have signposting and place-names in their own language, both minorities have chosen not to demand this. Elsewhere in the German- Scandinavian region, minorities have claimed this right. What is the reason behind the Danish and German minorities not having opted for onomastic equality? And how does the situation differ from other minority naming cases in this region? These questions, and some observations on how the minorities on the German-Danish border may be on their way to obtaining onomastic equality, will be discussed in this paper. INTRODUCTION Article 10.2.g. of the Council of Europe’s European Charter for Regional and National Minorities (ETS no. 148) calls for the possibility of public display of minority language place-names.1 This is in accordance with the Council of Europe’s Convention no. 157: Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities. Here, the right for national minorities to use place-names is expressed in Article 11, in particular sub-article 3,2 which allows for the possibility of public display of traditional minority language * Professor, University of Copenhagen, Denmark. -

Louise Arner Boyd (1887-1972) Author(S): Walter A

Obituary: Louise Arner Boyd (1887-1972) Author(s): Walter A. Wood and A. Lincoln Washburn Source: Geographical Review, Vol. 63, No. 2 (Apr., 1973), pp. 279-282 Published by: American Geographical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/213418 Accessed: 31/08/2008 17:22 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ags. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org GEOGRAPHICAL RECORD 279 Science, and served as dean of the Graduate School from 1949 to 1961. The uni- versity recognized his contributions and international status in 1962, when its highest faculty honor, a Boyd Professorship, was bestowed on him. -

Transnational Finnish Mobilities: Proceedings of Finnforum XI

Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen (Eds.) Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen This volume is based on a selection of papers presented at Johanna Leinonen and Auvo Kostiainen (Eds.) the conference FinnForum XI: Transnational Finnish Mobili- ties, held in Turku, Finland, in 2016. The twelve chapters dis- cuss two key issues of our time, mobility and transnational- ism, from the perspective of Finnish migration. The volume is divided into four sections. Part I, Mobile Pasts, Finland and Beyond, brings forth how Finland’s past – often imagined TRANSNATIONAL as more sedentary than today’s mobile world – was molded by various short and long-distance mobilities that occurred FINNISH MOBILITIES: both voluntarily and involuntarily. In Part II, Transnational Influences across the Atlantic, the focus is on sociocultural PROCEEDINGS OF transnationalism of Finnish migrants in the early 20th cen- tury United States. Taken together, Parts I and II show how FINNFORUM XI mobility and transnationalism are not unique features of our FINNISH MOBILITIES TRANSNATIONAL time, as scholars tend to portray them. Even before modern communication technologies and modes of transportation, migrants moved back and forth and nurtured transnational ties in various ways. Part III, Making of Contemporary Finn- ish America, examines how Finnishness is understood and maintained in North America today, focusing on the con- cepts of symbolic ethnicity and virtual villages. Part IV, Con- temporary Finnish Mobilities, centers on Finns’ present-day emigration patterns, repatriation experiences, and citizen- ship practices, illustrating how, globally speaking, Finns are privileged in their ability to be mobile and exercise transna- tionalism. Not only is the ability to move spread very uneven- ly, so is the capability to upkeep transnational connections, be they sociocultural, economic, political, or purely symbol- ic. -

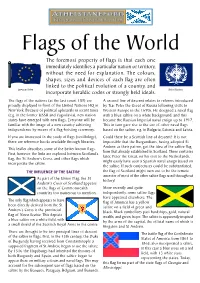

Flags of the World

ATHELSTANEFORD A SOME WELL KNOWN FLAGS Birthplace of Scotland’s Flag The name Japan means “The Land Canada, prior to 1965 used the of the Rising Sun” and this is British Red Ensign with the represented in the flag. The redness Canadian arms, though this was of the disc denotes passion and unpopular with the French sincerity and the whiteness Canadians. The country’s new flag represents honesty and purity. breaks all previous links. The maple leaf is the Another of the most famous flags Flags of the World traditional emblem of Canada, the white represents in the world is the flag of France, The foremost property of flags is that each one the vast snowy areas in the north, and the two red stripes which dates back to the represent the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. immediately identifies a particular nation or territory, revolution of 1789. The tricolour, The flag of the United States of America, the ‘Stars and comprising three vertical stripes, without the need for explanation. The colours, Stripes’, is one of the most recognisable flags is said to represent liberty, shapes, sizes and devices of each flag are often in the world. It was first adopted in 1777 equality and fraternity - the basis of the republican ideal. linked to the political evolution of a country, and during the War of Independence. The flag of Germany, as with many European Union United Nations The stars on the blue canton incorporate heraldic codes or strongly held ideals. European flags, is based on three represent the 50 states, and the horizontal stripes. -

This Sceptered Isle

This Sceptered Isle 1. It’s not Stonehenge, but one landscape in this place included a large standing stone known as the Odin Stone, where marriage ceremonies were conducted with each side holding hands through a hole in the stone. A late 18th century historian of this place claimed that that one monument was a ‘Temple of the Moon’, paired with a similarly shaped one he claimed was called the ‘Temple of the Sun’. According to one saga named for this place, while the men of the Earl Harald were sheltering from the snow, two of them went mad inside one ancient monument. That ancient monument was also inscribed by crusaders and others, including an inscription that says (*) ‘Thorny fucked, Helgi carved’ in runes. A storm uncovered a settlement in this place originally thought to be Pictish, but whose eight dwellings, linked by low covered passages, were shown by carbon dating to be Neolithic. For 10 points, name these Scottish islands, the location of prehistoric sites such as Maeshowe, the Standing Stones of Stenness and Skara Brae. ANSWER: Orkney Islands 2. Against Matthew Paris’ claim that the Schola Saxonum in Rome was founded by Ine of Wessex, William of Malmesbury suggested that it was founded by this ruler. In a letter to Osberht, Alcuin claimed how this ruler’s son ‘had not died for his sins, but the vengeance for the blood shed by’ this ruler. One structure ascribed to this ruler’s efforts has been called ‘a dead monument in an empty landscape’, though conflicts recorded in the Annales Cambriae may suggest the purpose of its construction. -

Norwegian and Swedish Forest Finn Research

Norwegian and Swedish Forest Finn Research Elaine Hasleton, BA, AG® [email protected] Check Church records to identify your ancestor – parish and farm Look for Finnish family names! Check the Norwegian bygdebøker for possible Finnish names. Utilize Finnskog Reference Books. (See book list). Try to tie into the 1823 time period and Gottlund’s 1823 census book. C.A. Gottlunds Folkmängden på Finnskogarne fra 1823. Once the farm is identified, use the Jarl Ericson books. Skogfinska släktnamn i Skandinavien book by Bladh, Myhrvold, Persson. Useful when you’ve learned your Finnish family names. Use unique sources, such as tax records which are one of the best sources to find genealogical information in Norway, Sweden, and Finland. Take a Family Tree DNA test, as they have a Forest Finn DNA Project. Contact Finnskog experts to check their databases. Coordinate with Elaine at [email protected] DNA steps: Be sure to submit your pedigree to Family Tree DNA Use Family Finder to help determine if it’s likely or not Exceptional books to expand your knowledge about the Forest Finns. The Forest Finns of Scandinavia by Maud Wedin Forest Finn Encounters by Oppenheim, Florence and Daniel Svensson. Give back by sharing your family information. Unique source content: Church records (Kirkebøker) Tax records (Skatteregister) Inventory records (Skifter) Old maps (Gamle karter) Legal records (Juridiska register) Military sources (Militære kilder/Militære ruller) Special unique sources: 1636 Household Exams of Finns in Orsa (Sweden) 1674 Census (Finns in Fryksdalen) (Sweden) 1686 Finnish Census (Norway) 1700 Finnish Census (Swedes and Finns) (Norway) 1706 Finnish Census of Hof parish (Norway) 1716 -17 Household exams Dalby parish (Sweden) C. -

Louise Arner Boyd Screening

Stage a community event about Unsung Women who Changed America Do-It-Yourself Screening Kit: Louise Arner Boyd Bring the story of this trailblazing explorer— the first woman to lead an expedition to the polar seas— to your community. ABOUT THE SERIES “People openly UNLADYLIKE2020 is an innovative multimedia series featuring diverse and told me the little-known American heroines from the early years of feminism, and the women who now follow in their footsteps. Presenting history in a bold new Arctic was a way, the rich biographies of 26 women who broke barriers in male-dominated place only for fields 100 years ago, such as science, business, politics, journalism, sports, and the arts, are brought back to life through rare archival imagery, men — that captivating original artwork and animation, and interviews with historians, for me to go descendants, and accomplished women of today who reflect on the influence where I did was of these pioneers. not to Narrated by Julianna Margulies (ER, The Good Wife, Billions) and Lorraine be taken Toussaint (Selma, Orange is the New Black, The Glorias), the series features 26 ten-to-twelve-minute animated documentary films released digitally on PBS’s seriously. flagship biography series American Masters, along with a television hour on Determination PBS showcasing the stories of trailblazers in politics and civil rights, plus a resource-rich interactive website, a grades 6 through 12 U.S. history and persistence curriculum on PBS LearningMedia, and a nationwide community engagement brought me to and screening initiative staged in partnership with public television stations the position I and community organizations. -

Schools of Scandinavia; Finland and Holland

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF EDUCATION BULLETIN, 1919, No. 29 SCHOOLS OF SCANDINAVIA; FINLAND AND HOLLAND By PETER H. PEARSON DIVISION OF FOREIGN EDUCATIONAL SYSTEMS BUREAU OF EDUCATION [Advance Sheets how the Biennial Survey of Education, 1916-1918] WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRIMING OFFICE 1919 ar ADDITIONAL COPIES 07 THIS PURUCATION MkT RE PROCURED nor, THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS POVERNI4ENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON, D. q. AT 19 CENTS PER COPY V SCHOOLS OF SCANDINAVIA, FINLAND, AND HOLLAND. ByPETER II. PEARSON: D,P1401, of 'Foreign EIIsestitmal Systems, Burros of Education. CONTENT9.The war In Its effects on the schools of ScandinaviaNorway: General characteristics of the school system; School gardens; School wistfore activities: Speech forms in the schools; Teachers' pen- sions; War conditions and the schools; Present trend In educational thought and school legislation- - Sweden: General view of the educational system; Care of the pupils' health; Religious Instruction in the elementary schools: Studies of the home locality; Development of the communal middle school; Obligatory continuation school; Educational activities apart from the schoolsDenmark: General survey of the educational system; National Polytechnic Institute; the people's high school; school excursions; Teachers' traintug, salaries, and status: Ar.ticulation betweep primary and secondary schoolsHollandThe schools of FinlandEducation in Iceland, by llolmfridur Armadottle THE WAR IN ITS EFFECTS ON THE SCHOOLS OF SCANDINAVIA. Though. the Scandinavian countries