01 September Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Love Stories: Narrative Ethics and the Novel from Stowe to James

American Love Stories: Narrative Ethics and the Novel from Stowe to James By Ashley Carson Barnes A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Dorothy Hale, Chair Professor Samuel Otter Professor Dorri Beam Professor Robert Alter Fall 2012 1 Abstract American Love Stories: Narrative Ethics and the Novel from Stowe to James by Ashley Carson Barnes Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Berkeley Professor Dorothy Hale, Chair “American Love Stories” argues for the continuity between two traditions often taken to be antagonistic: the sentimental novel of the mid-nineteenth century and the high modernism of Henry James. This continuity emerges in the love stories tracked here, from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Elizabeth Stuart Phelps’s The Gates Ajar, through Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Blithedale Romance and Herman Melville’s Pierre, to Elizabeth Stoddard’s The Morgesons and James’s The Golden Bowl. In these love stories—the other side of the gothic tradition described by Leslie Fiedler—desire is performed rather than repressed, and the self is less a private container than a public exhibit. This literary-historical claim works in tandem with the dissertation’s argument for revising narrative ethics. The recent ethical turn in literary criticism understands literature as practically engaging the emotions, especially varieties of love, that shape our social lives. It figures reading as a love story in its own right: an encounter with a text that might grant us intimacy with an authorial persona or else spurn our desire to grasp its alterity. -

Bard Digital Commons Jul2020

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Robert Kelly Manuscripts Robert Kelly Archive 7-2020 jul2020 Robert Kelly Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/rk_manuscripts JULY 2020 1 = = = = = 1. In mind alert growl, a lion cub hesitant at cloud. Yes, this is the place or is no other origin for what to do now. Growl, grow up and prowl the rich savannas of. 2. Birth of a pansy, old age of a rose. Remember the feel of when. Bruise in the sky, yes, so many yesses. JULY 2020 2 3. Keep wanting to want. The event enews itself in you. Animals who burrow in the earth often find light too bright to see. They walk right up to you and then. 4. Some day it will roar. Sunday. Till then suspect, uneasy feelingI should be doing something else. 5. Full grown on four thoughts stands clear. Nothing has been and been forgotten. The image speaks louder than the man. JULY 2020 3 The fact of the matter is matter. And here I thought it or I was growling. We’re just perpendiculars hanging from the sky. 1 July 2020 JULY 2020 4 = = = = = Give me just a tissue of belief to wipe the doubt from my eyes, let the day exist on its own terms far away from my jive for I was ocean too, like everyone and came across myself tp be. just be. Linger I said like Faust, linger be you beautiful or not, only what lingers matters. Or do I mean only what is gone? 1 July 2020 JULY 2020 5 = = = = = Something other has to start. -

And They Lived Happily Ever After : the Effects of Cultural Myths and Romantic Idealizations on Committed Relationships

Smith ScholarWorks Theses, Dissertations, and Projects 2007 And they lived happily ever after : the effects of cultural myths and romantic idealizations on committed relationships Jordana Lauren Metz Smith College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Metz, Jordana Lauren, "And they lived happily ever after : the effects of cultural myths and romantic idealizations on committed relationships" (2007). Masters Thesis, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses/1318 This Masters Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Projects by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jordana Lauren Metz And They Lived Happily Ever After: The Effects of Cultural Myths and Romantic Idealizations on Committed Relationships ABSTRACT This study explored the impact of idealized relationships, present in our media and culture, on committed relationships. The purpose of this study was to explore the ways that relationships are impacted by real and idealized relationship discrepancies. In addition, this research provided an initial assessment of the coping mechanisms utilized by partners as problem solving responses to the discrepancies. Twelve participants, self-identified as in a committed relationship with a partner and living together for over one year, participated in this study. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with questions focusing on how the participants’ relationships fit and do not fit into idealized notions of relationships, how their partnership is affected by this relationship discrepancy and the ways that they cope and respond to these effects. Findings indicated that many participants experienced feelings of discomfort, questioning and doubt in their relationship due to the prevalence of idealized relationships. -

Relationship Difficulties and Help-Seeking Behaviour Secondary Analysis of an Existing Data-Set

Research Report DFE-RR018 Relationship difficulties and help-seeking behaviour Secondary analysis of an existing data-set Josephine Ramm, Lester Coleman1 , Fiona Glenn and Penny Mansfield 1 Dr Lester Coleman, Head of Research at One Plus One, is the corresponding author – [email protected] Relationship difficulties and help-seeking behaviour Secondary analysis of an existing data-set FINAL REPORT Josephine Ramm, Lester Coleman1, Fiona Glenn and Penny Mansfield One Plus One June 2010 This research report was written before the new UK Government took office on 11 May 2010. As a result the content may not reflect current Government policy and may make reference to the Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF) which has now been replaced by the Department for Education (DFE). The views expressed in this report are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department for Education. 1 Dr Lester Coleman, Head of Research at One Plus One, is the corresponding author – [email protected] 2 Contents Executive Summary Chapter 1. Introduction & methodology 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Research questions 1.3 Sampling and methods 1.4 Research findings 1.5 Research limitations Chapter 2. Relationship difficulties 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Results 2.2.1 Types of difficulties raised by participants 2.2.2 Underlying issues 2.2.3 Consequences of relationship difficulties 2.2.4 Variation by gender 2.3 Conclusion 2.3.1 Summary of findings 2.3.2 Discussion Chapter 3. What factors help a relationship endure? 3.1 Introduction 3.2 Results 3.2.1 What makes a relationship endure? 3.2.2 What makes my relationship endure? 3.2.3 Variation by gender 3.3 Conclusion 3.3.1 Summary of findings 3.3.2 Discussion Chapter 4. -

George Woke Up, Frozen with Fear. He Opened His Eyes and Was Immediately Frightened of What Was Lying Next to Him. He Was Unsure

George woke up, frozen with fear. He opened his eyes and was immediately frightened of what was lying next to him. He was unsure of whether to scream or run from the bedroom: Should I scream or run from the bedroom? A velociraptor was sleeping in his bed, with closed eyes. Its breaths were sedated and stable; it snorted in through its snout and rasped out through its clenched, dagger-filled mouth. When he lifted his head, he noticed a thick, green tail spilling out from beneath the covers. It slumped from the side of the bed onto the floor. The beast shifted and groaned. It rolled its head on the pillow, using its razor-sharp claws to pick at the linen. George shifted onto his back and played dead. What the hell is going on? George thought as he moved his eyes from the ceiling to the wheezing beak beside him. He snapped back into a neutral supine position when the creature stirred again. He squeezed his eyes closed. When he allowed them to open, the sleeping raptor remained. Sleeping. He fought to quell his terror-fueled panting as best he could. Could raptors sense panic? Could they smell it? Like bees and dogs? George was too shocked to move, but didn’t want to remain so vulnerable and such an easy feast for the monster. Very slowly, George mouthed to himself. He began rolling in the opposite direction with care, as to not disturb the snoring raptor. It was working. He had successfully settled one foot on the hardwood floor. -

First Comes Love, Then What? Copyright © 2008 by Kimberly Beair All Rights Reserved

First Comes Love pages 1/2/08 4:27 PM Page v First Comes Love pages 1/2/08 4:27 PM Page vi First Comes Love, Then What? Copyright © 2008 by Kimberly Beair All rights reserved. International copyright secured. A Focus on the Family book published by Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Carol Stream, Illinois 60188 Focus on the Family and the accompanying logo and design are federally registered trade- marks of Focus on the Family, Colorado Springs, CO 80995. TYNDALE and Tyndale’s quill logo are registered trademarks of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. All Scripture quotations, unless otherwise indicated, are taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version®. NIV®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations marked (ESV) are taken from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version, copyright © 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a division of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. The majority of case examples presented in this book are fictional composites based on the author’s clinical experience with hundreds of clients through the years. Any resem- blance between these fictional characters and actual persons is coincidental. When clients’ actual stories have been used, people’s names and certain details of their stories have been changed to protect the privacy of the individuals involved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise— without prior written permission of Focus on the Family. -

2015 Programmers Picks

41ST SEATTLE INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL PROGRAMMERS’ PICKS PRESENTED BY DARK HORSE WINES GHADI – Not what you would expect from a Lebanese film – Ghadi is a sparkling, imaginative and joyous fable about a young boy with Down Syndrome that is mistaken for being an angel. Carl GOODNIGHT MOMMY – Unsettling and sophisticated auteur horror film surrounding twin brothers that are convinced their Spence post-facial surgery mother is an imposter. GRAZIELLA – Two outcasts try to make a new life for themselves ARTISTIC but can’t escape their past. Starring Denis Lavant (Leo Carax, Holy Motors) and Rossy De Palma (Pedro Alomodovar’s Tie Me DIRECTOR Up, Tie Me Down). I KISSED A GIRL – A smash hit in France! This sparkling Hollywood style romantic comedy revolves around the politically incorrect storyline of a man whose wedding plans to marry another man are derailed when he mistakenly falls in love with a Here’s a baker’s dozen of films – with the exception of a few woman. favorite filmmakers, I’ve focused mainly on new discoveries from around the world. The films that we have feted as KILLING FIELDS OF DR. HAING S. NGOR – Rare Archival galas and special presentations are not listed here but are footage, original animation, and new interviews not only capture also some of my top picks! Ngor’s tragic life story as a Cambodian genocide survivor and Oscar winning actor (The Killing Fields) but also engagingly EISEINSTEIN IN GUANAJUATO – Peter Greenaway, one of the provides a historical account of the circumstances that brought world’s most audacious filmmakers sheds light on Russia’s the Khmer Rouge to power and the Vietnamese occupation that greatest (and notorious) filmmaker and his flamboyant exploits in followed. -

Rhyn's Redemption Rhyn Trilogy, Book Three

Rhyn's Redemption Rhyn Trilogy, Book Three By Lizzy Ford http://www.GuerrillaWordfare.com/ Edited by Christine LePorte http://www.ChristineLePorte.com/ Cover art and design by Dafeenah http://www.indiedesignz.com/ Rhyn’s Redemption copyright 2012 by Lizzy Ford Cover art and design copyright 2012 by Dafeenah All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the author. The only exception is by a reviewer, who may quote short excerpts in a review. This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental. See other titles by Lizzy Ford http://www.GuerrillaWordfare.com You can follow the GW team on Twitter: @LizzyFord2010 @cleporte @dafeenajameel Twitter hashtags: #guerrillawriter, #fantasy, #romance, #paranormalromance, #rhyntrilogy Author’s Note “Rhyn’s Redemption” – end of the Trilogy, beginning of the Rhyn Eternal Series When I started the Rhyn Trilogy, it was with the intention of ending it after three books. I figured I’d detail Katie and Rhyn’s relationship and how they eventually became a couple. However, this past fall, after seeing the overwhelming reader support and feedback for the series to continue beyond the three books, I developed a different plan. I now consider the Rhyn Trilogy to be a prequel to the Rhyn Eternal series and more of a history of how all the players got to where they are when the Rhyn Eternal series launches this September. -

David Lessard - Poems

Poetry Series david lessard - poems - Publication Date: 2014 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive david lessard(september fourteenth, nineteen forty- one) I grew up in vermont. have also lived in new york state, virginia, nevada, new hampshire and currently live in central arizona. I was a respiratory care practitioner most of my life. I am now retired. I have an associate's degree in the health sciences. Working on a life-journal that totals over a 1,000 pages. (A shorter version that is 250 pages) A 'novel' of 165 pages and about 400 poems, make up the balance of my writings.(poemhunter and poetfreak) www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 A Capital Idea Money honey...that's what I want... In this age of buying and selling, Is there something, they're not telling? What does it cost them to sell? Much less than what we pay, (so why should they tell?) There would surely be a riot then, If we knew just what they spend. We'd all be up in arms and yelling, What they are keeping secret and not telling. The only trouble with profit is greed, as it satisfies no normal need; It's a road paved with bad intentions, No more health plans, no more pensions. We've nothing further more to gain, We've known all along where troubles lain; We're on a non-stop, hell-bound train, We're in a whirlpool, going down that drain. For what? Big bucks and corporation, All for the profit of one small nation; A nation of the powerful and few, Someday they crash...just like me and you. -

Computer Design in the Handweaving Process Susan Aileen Poague Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1987 Computer design in the handweaving process Susan Aileen Poague Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the Fine Arts Commons Recommended Citation Poague, Susan Aileen, "Computer design in the handweaving process " (1987). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 7965. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/7965 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Computer design in the handweaving process by Susan Aileen Poague / A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS ^Department: Art and Design Major; Craft Design Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames/ Iowa 1987 CopyrIght © Susan Alleen Poague, 1987. AH rights reserved II TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER I THE JACQUARD EVOLUTION—FROM LOOM-TO 4 COMPUTER AND BACK J, M, Jacquard and His Loom 4 Description of Jacquard's Invention 8 Charles Babbage and Herman Hollerith: 16 The First "Computers" What Is a Computer? 18 Bringing the Jacquard Loom to Computer Control 23 CHAPTER 2 -

The 5 Love Languages: the Secret to Love That Lasts

THE Five LOVE LANGUAGES THE Five LOVE LANGUAGES How to Express Heartfelt Commitment to Your Mate GARY CHAPMAN NORTHFIELD PUBLISHING CHICAGO © 1992, 1995, 2004 by Gary D. Chapman All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Scripture quotations, unless noted otherwise, are taken from the Holy Bible: New International Version®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House. All rights reserved. The use of selected references from various versions of the Bible in this publication does not necessarily imply publisher endorsement of the versions in their entirety. ISBN: 978-1-881273-15-6 To Karolyn, Shelley, and Derek Other Great Books by Gary Chapman The Five Love Languages Men’s Edition The Five Love Languages Gift Edition The Five Love Languages of Children The Five Love Languages of Teenagers The Five Love Languages for Singles Your Gift of Love Parenting Your Adult Child The Other Side of Love Loving Solutions Five Signs of a Loving Family Toward a Growing Marriage Hope for the Separated Covenant Marriage CONTENTS Acknowledgments 1. What Happens to Love After the Wedding? 2. Keeping the Love Tank Full 3. Falling in Love 4. Love Language #1: Words of Affirmation 5. Love Language #2: Quality Time 6. Love Language #3: Receiving Gifts 7. Love Language #4: Acts of Service 8. Love Language #5: Physical Touch 9. Discovering Your Primary Love Language 10. Love Is a Choice 11. -

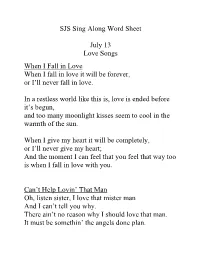

SJS Sing with Mary Ann East V2.Pdf

SJS Sing Along Word Sheet July 13 Love Songs When I Fall in Love When I fall in love it will be forever, or I’ll never fall in love. In a restless world like this is, love is ended before it’s begun, and too many moonlight kisses seem to cool in the warmth of the sun. When I give my heart it will be completely, or I’ll never give my heart; And the moment I can feel that you feel that way too is when I fall in love with you. Can’t Help Lovin’ That Man Oh, listen sister, I love that mister man And I can’t tell you why. There ain’t no reason why I should love that man. It must be somethin’ the angels done plan. Fish got to swim, birds got to fly, I got to love one man till I die, Can’t help lovin’ that man of mine. Tell me he’s lazy, tell me he’s slow, Tell me I’m crazy, maybe I know. Can’t help lovin’ that man of mine. When he’s goes away, that’s a rainy day, And when he comes back, that day is fine! The sun will shine! He can come home as late as can be, home without him is no home to me. Can’t help lovin’ that man of mine! Somebody Loves Me Somebody love me, I wonder who, I wonder who it can be. Somebody loves me, I wish I knew who it can be worries me.