Labor Organization, Autonomy and Democratization in Egypt (2011-2016)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 4 Logistics-Related Facilities and Operation: Land Transport

Chapter 4 Logistics-related Facilities and Operation: Land Transport THE STUDY ON MULTIMODAL TRANSPORT AND LOGISTICS SYSTEM OF THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN REGION AND MASTER PLAN FINAL REPORT Chapter 4 Logistics-related Facilities and Operation: Land Transport 4.1 Introduction This chapter explores the current conditions of land transportation modes and facilities. Transport modes including roads, railways, and inland waterways in Egypt are assessed, focusing on their roles in the logistics system. Inland transport facilities including dry ports (facilities adopted primarily to decongest sea ports from containers) and to less extent, border crossing ports, are also investigated based on the data available. In order to enhance the logistics system, the role of private stakeholders and the main governmental organizations whose functions have impact on logistics are considered. Finally, the bottlenecks are identified and countermeasures are recommended to realize an efficient logistics system. 4.1.1 Current Trend of Different Transport Modes Sharing The trends and developments shaping the freight transport industry have great impact on the assigned freight volumes carried on the different inland transport modes. A trend that can be commonly observed in several countries around the world is the continuous increase in the share of road freight transport rather than other modes. Such a trend creates tremendous pressure on the road network. Japan for instance faces a situation where road freight’s share is increasing while the share of the other -

Egypt Nets Billions in Investment

www.amcham.org.eg/bmonthly NOT FOR SALE APRIL 2015 ALSO INSIDE L L AFFORDABLE HOUSING HEATS UP L L WHAT THE VAT MEANS FOR YOU L L WEARABLE ART Landslide Egypt nets billions in investment APRIL 2015 VOLUME 32 | ISSUE 4 36 Cleaning up The March economic summit in Sharm el-Sheikh netted Egypt around $38.2 billion in deals as well as another $12.5 billion in aid from the Gulf. Officials successfully marketed the country to the international media as a business-friendly destination on the rise, despite ongoing economic challenges. Cover Design: Nessim N. Hanna Inside 28 20 Editor’s Note 22 Viewpoint The Newsroom 24 In Brief The news in a nutshell 28 Region Notes News from around the region © Copyright Business Monthly 2015. All rights reserved. No part of this magazine may be reproduced without the prior written consent of the editor. The opinions expressed in Business Monthly do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Chamber of Commerce in Egypt. Business Monthly – 16 I April 2015 APRIL 2015 VOLUME 32 | ISSUE 4 33 52 56 Market Watch Executive Life 44 52 Stock Analysis Dining Out Market pulls back in run-up to Genghis Khan serves up authentic economic summit Chinese food 45 Capital Markets 54 A glance at stocks & bonds Fashion Art & Sole 47 Money & Banking Forex and deposits 48 Key Indicators The economy at a glance The Chamber In Depth 49 Egypt-U.S. Trade Imports and exports 30 58 Affordable housing megaprojects Corporate Clinic Events may not be affordable for most Developers eye “middle-income” 50 62 Six degrees Member News market Cairo tech map shows that success 66 33 depends on connections Announcements Mulling the pros and cons of the VAT 67 How the tax switch could affect SMEs Classifieds 68 Media Lite An irreverent glance at the press Business Monthly – 18 I April 2015 Editor’s Note Director of Publications & Research Khaled F. -

U.S.-Egyptian Relations Since the 2011 Revolution: the Limits of Leverage

U.S.-Egyptian Relations Since the 2011 Revolution: The Limits of Leverage An Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of Politics in partial fulfillment of the Honors Program by Benjamin Wolkov April 29, 2015 Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1. A History of U.S.-Egyptian Relations 7 Chapter 2. Foreign Policy Framework 33 Chapter 3. The Fall of Mubarak, the Rise of the SCAF 53 Chapter 4. Morsi’s Presidency 82 Chapter 5. Relations Under Sisi 115 Conclusion 145 Bibliography 160 1 Introduction Over the past several decades, the United States and Egypt have had a special relationship built around military cooperation and the pursuit of mutual interests in the Middle East. At one point, Egypt was the primary nemesis of American interests in the region as it sought to spread its own form of Arab socialism in cooperation with the Soviet Union. However, since President Anwar Sadat’s decision to sign the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty in 1979, Egypt has proven a bulwark of the United States interests it once opposed. Specifically, those interests are peace with Israel, the continued flow of oil, American control of the region, and stability within the Middle East. In addition to ensuring these interests, the special friendship has given the United States privileges with Egypt, including the use of Egyptian airspace, expedited transit through the Suez Canal for American warships, and the basing of an extraordinary rendition program on Egyptian territory. Noticeably, the United States has developed its relationship with Egypt on military grounds, concentrating on national security rather than issues such as the economy or human rights. -

Omar Ashraf Ali Goda Shibin Al Kawm, Al Minufiyah, Egypt - Phone: +201027316772, +201013935495

Omar Ashraf Ali Goda Shibin Al Kawm, Al Minufiyah, Egypt - Phone: +201027316772, +201013935495 Email: [email protected] - Linkedin profile: https://www.linkedin.com/in/omar-ashraf-35384a180 Data of Birth: 1/10/1997 SUMMARY I am self –motivated, ambitious and eager to learn. Looking for both personal and professional growth makes me capable of working under pressure. Seeking for a challenging opportunity to work as an electrical power engineer to enhance my analytic skills and shape my own career. EDUCATION Bachelor’s Degree in Electrical Power and Machines Engineering, Pyramids Higher Institute of Engineering Department: Electrical Engineering Major: Power and Machines Graduation project: (Designed the distribution systems for a population city) Project Grade: Excellent (A+) Graduation Year: 2020 EXPERIENCE Maintenance Engineer , RAYA (from 1 January 2021 to present) Report daily activities to CS TL/ CS SV and service helpdesk. Respond to customers’ calls and fix them based on agreed upon quality standards and customers’ SLAs. Perform new ATM installations, ATM staging or sites inspection and other planned preventive maintenance visits Assist Customer in regards to (training, phone support, onsite support) Close effectively his calls on incidents management system. Keep and maintain all his HW & SW tools in a healthy condition and keep reporting continuously the cases of tools failure or any extra tools needed to his Senior / Team leader. Maintenance Engineer , Police Academy. (from 1 September 2020 to 31 December 2020 -

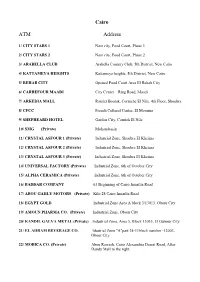

Cairo ATM Address

Cairo ATM Address 1/ CITY STARS 1 Nasr city, Food Court, Phase 1 2/ CITY STARS 2 Nasr city, Food Court, Phase 2 3/ ARABELLA CLUB Arabella Country Club, 5th District, New Cairo 4/ KATTAMEYA HEIGHTS Kattameya heights, 5th District, New Cairo 5/ REHAB CITY Opened Food Court Area El Rehab City 6/ CARREFOUR MAADI City Center – Ring Road, Maadi 7/ ARKEDIA MALL Ramlet Boulak, Corniche El Nile, 4th Floor, Shoubra 8/ CFCC French Cultural Center, El Mounira 9/ SHEPHEARD HOTEL Garden City, Cornish El Nile 10/ SMG (Private) Mohandessin 11/ CRYSTAL ASFOUR 1 (Private) Industrial Zone, Shoubra El Kheima 12/ CRYSTAL ASFOUR 2 (Private) Industrial Zone, Shoubra El Kheima 13/ CRYSTAL ASFOUR 3 (Private) Industrial Zone, Shoubra El Kheima 14/ UNIVERSAL FACTORY (Private) Industrial Zone, 6th of October City 15/ ALPHA CERAMICA (Private) Industrial Zone, 6th of October City 16/ BADDAR COMPANY 63 Beginning of Cairo Ismailia Road 17/ ABOU GAHLY MOTORS (Private) Kilo 28 Cairo Ismailia Road 18/ EGYPT GOLD Industrial Zone Area A block 3/13013, Obour City 19/ AMOUN PHARMA CO. (Private) Industrial Zone, Obour City 20/ KANDIL GALVA METAL (Private) Industrial Zone, Area 5, Block 13035, El Oubour City 21/ EL AHRAM BEVERAGE CO. Idustrial Zone "A"part 24-11block number -12003, Obour City 22/ MOBICA CO. (Private) Abou Rawash, Cairo Alexandria Desert Road, After Dandy Mall to the right. 23/ COCA COLA (Pivate) Abou El Ghyet, Al kanatr Al Khayreya Road, Kaliuob Alexandria ATM Address 1/ PHARCO PHARM 1 Alexandria Cairo Desert Road, Pharco Pharmaceutical Company 2/ CARREFOUR ALEXANDRIA City Center- Alexandria 3/ SAN STEFANO MALL El Amria, Alexandria 4/ ALEXANDRIA PORT Alexandria 5/ DEKHILA PORT El Dekhila, Alexandria 6/ ABOU QUIER FERTLIZER Eltabia, Rasheed Line, Alexandria 7/ PIRELLI CO. -

Analysis of Self-Developed Areas in Egypt

Ain Shams University Faculty of Engineering Department of Urban Planning and Design Analysis of Self-Developed Areas in Egypt Dissertation Submitted For the Fulfillment of The Master of Science Degree in Urban Planning By Mona A. Mannoun Supervised by Prof. Dr. Mohamed A. Salheen Professor - Department of Urban Planning and Design Faculty of Engineering – Ain Shams University Dr. Randa A. Mahmoud Assistant Professor - Department of Urban Planning and Design Faculty of Engineering – Ain Shams University 2014 Approval sheet For the Thesis: Analysis of Self-Developed areas in Egypt By Eng. Mona Abd-el-Raouf Eissa Mannoun A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Engineering-Ain Shams University in partial fulfillments of the requirements for the M.Sc. degree in Urban Planning and Design Engineering Approved by: Name Signature Prof. Dr. Mohamed Abd el Karim Salheen Prof. Urban Planning Department Faculty of Engineering - Ain Shams University Dr. Randa Abd el Aziz Mahmoud Assistant Prof. Urban Planning Department Faculty of Engineering - Ain Shams University Examiners Committee For the Thesis: Analysis of Self-Developed areas in Egypt By Eng. Mona Abd-el-Raouf Eissa Mannoun A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Engineering-Ain Shams University in partial fulfillments of the requirements for the M.Sc. degree in Urban Planning and Design Engineering Name, title and affiliation Signature Prof. Dr. Sahar Mohamed Attia Head of Architecture Department, Faculty of Engineering – Cairo University Prof. Dr. Shafak ElWakil Professor - Urban Planning Department Faculty of Engineering - Ain Shams University Prof. Dr. Mohamed Abd el Karim Salheen Professor - Urban Planning Department Faculty of Engineering - Ain Shams University Disclaimer This dissertation is submitted to Ain Shams University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in urban planning Engineering. -

Sherifa Zuhur and Marlyn Tadros

ZUHUR / TADROS: EGYPT’S CONSPIRACY DISCOURSE EGYPT’S CONSPIRACY DISCOURSE: LIBERALS, COPTS AND ISLAMISTS Sherifa Zuhur and Marlyn Tadros Dr. Zuhur, a visiting scholar at the Center for Middle Eastern Studies, University of California, Berkeley, was a research professor of national security at the Strategic Studies Institute at the U.S. Army War College from 2004 to 2009. Dr. Tadros is a research affiliate at the Middle East Center of Northeastern University and professor of Web Development and Interactive Media at the Arts Institute of New England. dward Said’s concept of oriental- dered behavior not necessarily present in a ism was developed from his per- society like Egypt? Or might it ameliorate ception of the role of scholarship Western ills: anomie, materialism, lack of in the West’s exploitation of the compassion, a quest to control valuable EEast for the purpose of conquest and the resources and militarism? maintenance of political power. It was not Ian Buruma and Avishai Margalit have simply a construct of Eastern inferiority defined occidentalism as anti-Westernism, versus Western superiority. Hassan Hanafi, anti-modernism and anti-colonialism, trac- chair of philosophy at Cairo University, ing it to scholars of the Romantic Group first encouraged a “science of occidental- or the Buddhist Hegelian Kyoto school ism” to counter orientalist studies.1 How- meeting in 1942.3 There are many similari- ever, as Syrian philosopher Sadiq al-Azm ties between this Asian political antipathy has suggested, one must heed Said’s to the West and types emerging in Egypt. warning to the subjects and victims of However, occidentalism, like orientalism, orientalism against the dangers of apply- is also a means of rendering the Other as ing the readily available structures, styles exotic, desirable and permeable. -

ISLAMIC DEMOCRACY from EGYPT's ARAB SPRING by JULES

ISLAMIC DEMOCRACY FROM EGYPT’S ARAB SPRING by JULES M. SCALISI A Capstone Project submitted to the Graduate School-Camden Rutgers-The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN LIBERAL STUDIES under the direction of Dr. Michael Rossi Approved by: ____________________________________ Dr. Michael Rossi, signed December 31, 2012 Camden, New Jersey January 2013 i ABSTRACT OF THE CAPSTONE ISLAMIC DEMOCRACY FROM EGYPT’S ARAB SPRING By JULES M. SCALISI Capstone Director Dr. Michael Rossi The collective action by Arabs throughout North Africa, the Middle East, and Southwest Asia has been a source of both joy and anxiety for the western world. When Tunisians took to the streets on December 18, 2010 they could not have imagined how the chain of events they had just begun would change the world forever. Arab Spring has granted new found freedoms to citizens in that part of the world. Many of these nations have seen new, democratically elected governments take hold. As the West rejoices for freedom’s victories, we cannot help but wonder how the long term changes in each country will impact us. With this new hope comes a sense of uncertainty. Is a democratically elected government compatible with the cultures and traditions of the Muslim world? Is there concern that a democratically elected head of state will resort to the type of strongman politics which results in a blended, or hybrid regime that has become common to the region? Will the wide-spread animosity that many Arabs feel ii against the United States carry over into politics? My aim with this project is to apply these questions and others to a single nation, as I examine the Egyptian Arab Spring movement. -

Egypt As a Woman: Nationalism, Gender, and Politics'

H-Women Yilmaz on Baron, 'Egypt As a Woman: Nationalism, Gender, and Politics' Review published on Wednesday, October 22, 2008 Beth Baron. Egypt As a Woman: Nationalism, Gender, and Politics. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004. 292 pp. $60.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-520-23857-2. Reviewed by Hale Yilmaz Published on H-Women (October, 2008) Commissioned by Holly S. Hurlburt Nationalism, Gender, and Politics in Egypt In Egypt as a Woman Beth Baron explores the connections between Egyptian nationalism, gendered images and discourses of the nation, and the politics of elite Egyptian women from the late nineteenth century to World War Two, focusing on the interwar period. Baron builds on earlier works on Egyptian nationalist and women's history (especially Margot Badran's and her own) and draws on a wide array of primary sources such as newspapers, magazines, archival records, memoirs, literary sources such as ballads and plays, and visual sources such as cartoons, photographs, and monuments, as well as on the scholarship on nationalism, feminism, and gender. This book can be read as a monograph focused on the connections between nationalism, gender, and politics, or it can be read as a collection of essays on these themes. (Parts of three of the chapters had appeared earlier in edited volumes.) The book's two parts focus on images of the nation, and the politics of women nationalists. It opens with the story of the official ceremony for the unveiling of Mahmud Mukhtar's monumental sculpture Nahdat Misr (The Awakening of Egypt) depicting Egypt as a woman. Baron draws attention to the paradox of the complete absence of women from a national ceremony celebrating a work in which woman represented the nation. -

The Muslim Brotherhood's

chapter 9 The Muslim Brotherhood’s ‘Virtuous society’ and State Developmentalism in Egypt: The Politics of ‘Goodness’ Marie Vannetzel Abstract The rise of Islamists in Arab countries has often been explained by their capacity to offer an alternative path of development, based on a religious vision and on a paral- lel welfare sector, challenging post-independence developmentalist states. Taking the case of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, and building on ethnographic fieldwork, this chapter aims to contribute to this debate, exploring how conflict and cooperation were deeply intertwined in the relationships between this movement and Mubarak’s regime. Rather than postulating any structural polarisation, or—in contrast—any simplistic authoritarian coalition, the author argues that the vision of two models of development opposing one another unravels when we move from abstract approach- es towards empirical studies. On the ground, both the Muslim Brotherhood and the former regime elites participated in what the author calls the politics of ‘goodness’ (khayr), which she defines as a conflictual consensus built on entrenched welfare net- works, and on an imaginary matrix mixing various discursive repertoires of state de- velopmentalism and religious welfare. The chapter also elaborates an interpretative framework to aid understanding of the sudden rise and fall of the Brotherhood in the post-2011 period, showing that, beyond its failure, what is at stake is the breakdown of the politics of ‘goodness’ altogether. 1 Introduction Islamists’ momentum in Arab countries has often been explained by their ca- pacity to offer an alternative path of development, based on a religious vision and on a ‘shadow and parallel welfare system […] with a profound ideologi- cal impact on society’ (Bibars, 2001, 107), through which they challenged post- independence developmentalist states (Sullivan and Abed-Kotob, 1999). -

The Right to Information in Egypt and Prospects of Renegotiating a New Social Order

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 6-1-2017 The right to information in Egypt and prospects of renegotiating a new social order Farida Ibrahim Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation Ibrahim, F. (2017).The right to information in Egypt and prospects of renegotiating a new social order [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/680 MLA Citation Ibrahim, Farida. The right to information in Egypt and prospects of renegotiating a new social order. 2017. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/680 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American University in Cairo School of Global Affairs and Public Policy The Right to Information in Egypt and Prospects of Renegotiating a New Social Order A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Law In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the LL.M. Degree in International and Comparative Law By Farida Mohamed Ahmed Ibrahim February 2017 The American University in Cairo School of Global Affairs and Public Policy The RIGHT TO INFORMATION IN EGYPT AND PROSPECTS OF RENEGOTIATING A NEW SOCIAL ORDER A Thesis Submitted by Farida Mohamed Ahmed Ibrahim to the Department of Law February 2017 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the LL.M. -

Militär-Kampfgas Gegen De Monstranten?

kultur magazin Nr. 5 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- kultur magazin Nr. 5 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- kultur magazin Nr. 5 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2011/2013..........................................15 Die Beiträge im EinzelnenVon den Parlaments- zu den Präsidentschaftswahlen 2012.............15 Die Präsidentschaftswahlen vom Mai/Juni 2012....................................16 Was ist die größere Gefahr? ..............17 Mohammed Mursis Präsidentschaft Der arabische Frühling vor dem Ende (22.8.2013) 4 (21.8.2013)..................................................18 Zwei Elemente Mursi´s Präsidentschaft Das Drama der syrischen Revolution (21.8.2013) ...........................................................7 18 Hier eine Zusammenfassung der Das Blutbad der Putschisten (17.8.2013) Ereignisse: .........................................11 18 Probleme des syrischen Widerstandes (10.6.2012)..................................................20 Tahrir 3.0 (3.7.2013) Egypt: Revolution and Conterrevolution12 Table of Contents (14.12.2012)................................................21 Zwischenkultur magazin Mubarak nr. 3 und ...................................... Mursi (21.8.2013)2 Economic growth rate and wealth13 per capita / Die Beiträge im Einzelnen ...........................2 employed (7.3.2012)...................................22