Accounts of Knowledge Production, Circulation and Consumption in Transitional Egypt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women and Political Change: Evidence from the Egyptian Revolution Nelly El Mallakh, Mathilde Maurel, Biagio Speciale

king Pape or r W s fondation pour les études et recherches sur le développement international e D 116 i e December ic ve 2014 ol lopment P Women and political change: Evidence from the Egyptian revolution Nelly El Mallakh, mathilde Maurel, Biagio Speciale Nelly El Mallakh, PhD candidate, teaching assistant at the Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, Centre d’Economie de la Sorbonne and Assistant Lecturer of Economics at the Faculty of Economics and Political Science, Cairo University. Mathilde Maurel, Director of research at the Université Paris 1 Panthéon- Sorbonne, Centre d’Economie de la Sorbonne, Senior Researcher in Economics at CNRS and Senior Fellow at Ferdi. Biagio Speciale, Lecturer at the Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, Centre d’Economie de la Sorbonne Abstract We analyze the effects of the 2011 Egyptian revolution on the relative labor market conditions of women and men using panel information from the Egypt Labor Market Panel Survey (ELMPS). We construct our measure of intensity of the revolution – the governorate-level number of martyrs, i.e. demonstrators who died during the protests - using unique information from the Statistical Database of the Egyptian Revolution. We find that the revolution has reduced the gender gap in labor force participation, employment, and probability of working in the private sector, and it has caused an increase in women’s probability of working in the informal sector. The political change has affected mostly the relative labor market outcomes of women in households at the bottom of the pre-revolution income distribution. We link these findings to the litera- ture showing how a relevant temporary shock to the labor division between women and men can have long run consequences on the role of women in society. -

The Political Economy of the New Egyptian Republic

ﺑﺤﻮث اﻟﻘﺎﻫﺮة ﻓﻲ اﻟﻌﻠﻮم اﻻﺟﺘﻤﺎﻋﻴﺔ Hopkins The Political Economy of اﻹﻗﺘﺼﺎد اﻟﺴﻴﺎﺳﻰ the New Egyptian Republic ﻟﻠﺠﻤﻬﻮرﻳﺔ اﳉﺪﻳﺪة ﻓﻰ ﻣﺼﺮ The Political Economy of the New Egyptian of the New Republic Economy The Political Edited by ﲢﺮﻳﺮ Nicholas S. Hopkins ﻧﻴﻜﻮﻻس ﻫﻮﺑﻜﻨﺰ Contributors اﳌﺸﺎرﻛﻮن Deena Abdelmonem Zeinab Abul-Magd زﻳﻨﺐ أﺑﻮ اﻟﺪ دﻳﻨﺎ ﻋﺒﺪ اﳌﻨﻌﻢ Yasmine Ahmed Sandrine Gamblin ﺳﺎﻧﺪرﻳﻦ ﺟﺎﻣﺒﻼن ﻳﺎﺳﻤﲔ أﺣﻤﺪ Ellis Goldberg Clement M. Henry ﻛﻠﻴﻤﻨﺖ ﻫﻨﺮى إﻟﻴﺲ ﺟﻮﻟﺪﺑﻴﺮج SOCIAL SCIENCE IN CAIRO PAPERS Dina Makram-Ebeid Hans Christian Korsholm Nielsen ﻫﺎﻧﺰ ﻛﺮﻳﺴﺘﻴﺎن ﻛﻮرﺷﻠﻢ ﻧﻴﻠﺴﻦ دﻳﻨﺎ ﻣﻜﺮم ﻋﺒﻴﺪ David Sims دﻳﭭﻴﺪ ﺳﻴﻤﺰ Volume ﻣﺠﻠﺪ 33 ٣٣ Number ﻋﺪد 4 ٤ ﻟﻘﺪ اﺛﺒﺘﺖ ﺑﺤﻮث اﻟﻘﺎﻫﺮة ﻓﻰ اﻟﻌﻠﻮم اﻻﺟﺘﻤﺎﻋﻴﺔ أﻧﻬﺎ ﻣﻨﻬﻞ ﻻ ﻏﻨﻰ ﻋﻨﻪ ﻟﻜﻞ ﻣﻦ اﻟﻘﺎرئ اﻟﻌﺎدى واﳌﺘﺨﺼﺺ ﻓﻰ ﺷﺌﻮن CAIRO PAPERS IN SOCIAL SCIENCE is a valuable resource for Middle East specialists اﻟﺸﺮق اﻷوﺳﻂ. وﺗﻌﺮض ﻫﺬه اﻟﻜﺘﻴﺒﺎت اﻟﺮﺑﻊ ﺳﻨﻮﻳﺔ - اﻟﺘﻰ ﺗﺼﺪر ﻣﻨﺬ ﻋﺎم ١٩٧٧ - ﻧﺘﺎﺋﺞ اﻟﺒﺤﻮث اﻟﺘﻰ ﻗﺎم ﺑﻬﺎ ﺑﺎﺣﺜﻮن and non-specialists. Published quarterly since 1977, these monographs present the results of ﻣﺤﻠﻴﻮن وزاﺋﺮون ﻓﻰ ﻣﺠﺎﻻت ﻣﺘﻨﻮﻋﺔ ﻣﻦ اﳌﻮﺿﻮﻋﺎت اﻟﺴﻴﺎﺳﻴﺔ واﻻﻗﺘﺼﺎدﻳﺔ واﻻﺟﺘﻤﺎﻋﻴﺔ واﻟﺘﺎرﻳﺨﻴﺔ ﺑﺎﻟﺸﺮق اﻷوﺳﻂ. ,current research on a wide range of social, economic, and political issues in the Middle East وﺗﺮﺣﺐ ﻫﻴﺌﺔ ﲢﺮﻳﺮ ﺑﺤﻮث اﻟﻘﺎﻫﺮة ﺑﺎﳌﻘﺎﻻت اﳌﺘﻌﻠﻘﺔ ﺑﻬﺬه اﻟﺎﻻت ﻟﻠﻨﻈﺮ ﻓﻰ ﻣﺪى ﺻﻼﺣﻴﺘﻬﺎ ﻟﻠﻨﺸﺮ. وﻳﺮاﻋﻰ ان ﻳﻜﻮن اﻟﺒﺤﺚ .and include historical perspectives ﻓﻰ ﺣﺪود ١٥٠ ﺻﻔﺤﺔ ﻣﻊ ﺗﺮك ﻣﺴﺎﻓﺘﲔ ﺑﲔ اﻟﺴﻄﻮر، وﺗﺴﻠﻢ ﻣﻨﻪ ﻧﺴﺨﺔ ﻣﻄﺒﻮﻋﺔ وأﺧﺮى ﻋﻠﻰ اﺳﻄﻮاﻧﺔ ﻛﻤﺒﻴﻮﺗﺮ (ﻣﺎﻛﻨﺘﻮش Submissions of studies relevant to these areas are invited. Manuscripts submitted should be أو ﻣﻴﻜﺮوﺳﻮﻓﺖ وورد). أﻣﺎ ﺑﺨﺼﻮص ﻛﺘﺎﺑﺔ اﳌﺮاﺟﻊ، ﻓﻴﺠﺐ ان ﺗﺘﻮاﻓﻖ ﻣﻊ اﻟﺸﻜﻞ اﳌﺘﻔﻖ ﻋﻠﻴﻪ ﻓﻰ ﻛﺘﺎب ”اﻻﺳﻠﻮب ﳉﺎﻣﻌﺔ around 150 doublespaced typewritten pages in hard copy and on disk (Macintosh or Microsoft ﺷﻴﻜﺎﻏﻮ“ (The Chicago Manual of Style) ﺣﻴﺚ ﺗﻜﻮن اﻟﻬﻮاﻣﺶ ﻓﻰ ﻧﻬﺎﻳﺔ ﻛﻞ ﺻﻔﺤﺔ، أو اﻟﺸﻜﻞ اﳌﺘﻔﻖ ﻋﻠﻴﻪ ﻓﻰ Word). -

News Coverage Prepared For: the European Union Delegation to Egypt

News Coverage prepared for: The European Union delegation to Egypt . Disclaimer: “This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of authors of articles and under no circumstances are regarded as reflecting the position of IPSOS or the European Union.” 1 . Thematic Headlines Domestic Scene Egyptians in Greece Call for Sacking Envoy Protesters Prevent PM from Exiting Ministry Premises 103,000 Egyptian Expats Vote in 2nd Phase of Elections Sabahi: I Will Stand Against Israel to Protect Palestinian Rights Court to Examine 200 Complaints to Nullify Elections in Cairo, Halt Them in Giza Presidential Hopeful Abu-Ismail: US Contact Huge Victory to Islamists FJP: The Constituent Assembly Hands Cuffs the Parliament Mubarak’s Wealth Advisory Council Holds Its First Meeting El-Ganzouri: The Economic Situation Is Devastating Hatata: SCAF Has No Political Experience SCAF Denies Mulla’s Statement Interior Minister Meets 1000 Officers Elections Updates in Al-Masry Al-Youm newspaper. Elections Updates in Al-Tahrir newspaper. MB Guide to Members: Be Modest and Remove Copts’ Fears Investigations of Mohamed Mahmoud Clashes Start within Days General Elections Updates in al-Ahram First Phase Polls Results Annulled in Alexandria’s Third Constituency Al-Nour Calls Cooperation with Freedom and Justice Field Marshal Tantawi visits Tahrir Square Ahmad Zwel Meets Field Marshal Tantawi Elections Updates in al-Akhbar Israel’s Ambassador Arrives Today The Egyptian Mufti is Number 12 on the List of the World’s Most Influential People Sharaf Apologizes 2 Newspapers (12/12/2011) Page: 1 Author: Muhammad Anz Al-Nour Calls Cooperation with Freedom and Justice Liberal parties coordinated to support 51 candidates in the second phase of the elections. -

A History of Women's Liberation in Egypt

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College 8-1-2017 Global Intersections: a History of Women's Liberation in Egypt Jordan Earls Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Earls, Jordan, "Global Intersections: a History of Women's Liberation in Egypt" (2017). University Honors Theses. Paper 506. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.511 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Global Intersections: A History of Women’s Liberation in Egypt by Jordan Earls An undergraduate honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in University Honors and Social Science Thesis Adviser Taghrid Khuri Portland State University 2017 1 Introduction The struggle of women against constraints placed upon them because of gender is one historically shared worldwide and continues today. In 1989, Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term “intersectional feminism” to describe how intersections of oppression impact women to varying degrees and argued that the goal of feminism must be to challenge these intersections. To not challenge these intersections is to, instead, reproduce them. Crenshaw demonstrates that the failure of American feminism to adequately interrogate the problems of racism caused feminism in the US to replicate and reinforce the racism women of color faced. Likewise, civil rights movements to end racism largely ignored the oppression of women by patriarchy and, in so doing, reproduced the subordination of women. -

True and False Confessions: the Efficacy of Torture and Brutal

Chapter 7 True and False Confessions The Efficacy of Torture and Brutal Interrogations Central to the debate on the use of “enhanced” interrogation techniques is the question of whether those techniques are effective in gaining intelligence. If the techniques are the only way to get actionable intelligence that prevents terrorist attacks, their use presents a moral dilemma for some. On the other hand, if brutality does not produce useful intelligence — that is, it is not better at getting information than other methods — the debate is moot. This chapter focuses on the effectiveness of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation technique program. There are far fewer people who defend brutal interrogations by the military. Most of the military’s mistreatment of captives was not authorized in detail at high levels, and some was entirely unauthorized. Many military captives were either foot soldiers or were entirely innocent, and had no valuable intelligence to reveal. Many of the perpetrators of abuse in the military were young interrogators with limited training and experience, or were not interrogators at all. The officials who authorized the CIA’s interrogation program have consistently maintained that it produced useful intelligence, led to the capture of terrorist suspects, disrupted terrorist attacks, and saved American lives. Vice President Dick Cheney, in a 2009 speech, stated that the enhanced interrogation of captives “prevented the violent death of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of innocent people.” President George W. Bush similarly stated in his memoirs that “[t]he CIA interrogation program saved lives,” and “helped break up plots to attack military and diplomatic facilities abroad, Heathrow Airport and Canary Wharf in London, and multiple targets in the United States.” John Brennan, President Obama’s recent nominee for CIA director, said, of the CIA’s program in a televised interview in 2007, “[t]here [has] been a lot of information that has come out from these interrogation procedures. -

Russia Strives to Assert Primacy, Rein in Turkish Ambitions in Syria

UK £2 Issue 189, Year 4 January 20, 2019 EU €2.50 www.thearabweekly.com Interview Recording Egypt’s minister abuses of of finance Palestinian rights Page 19 Page 13 Russia strives to assert primacy, rein in Turkish ambitions in Syria ► The withdrawal of the 2,000 American troops raises the question of which power will take over once the United States leaves. Thomas Seibert highlight Moscow’s strong reserva- tions about Turkey’s manoeuvres. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Istanbul Lavrov has said the Kremlin ex- pected the Syrian government to ussia seems determined take over territory in eastern Syria to assert its position as following the US withdrawal. He the strongest political and asserted it was necessary to fully R military player in Syria restore Syria’s sovereignty, add- while local and international pow- ing that Turkey’s plan to create a ers scramble to fill the expected buffer zone should be seen in that vacuum after the planned US with- context. drawal from the country. By sending military police to the With the US and Kurdish allies area west of Manbij in northern Syr- controlling approximately 25% of ia, Moscow made it clear that Rus- north-eastern Syria, the withdrawal sia does not intend to give Turkey a of the 2,000 American troops raises free hand in the region, said Kerim the question of which power will Has, a Moscow-based analyst of take over once the United States Russian-Turkish relations. leaves. The deployment demonstrated Turkish President Recep Tayyip “that Russia opts [for] its own pres- Erdogan told lawmakers of his rul- ence to avert Turkish demands for a ing party that he raised the possible military advancement,” Has said via creation of a “safe zone” in north- e-mail. -

WORLD REPORT 2021 EVENTS of 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH 350 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10118-3299 HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH WORLD REPORT 2021 EVENTS OF 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH 350 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10118-3299 HUMAN www.hrw.org RIGHTS WATCH This 31st annual World Report summarizes human rights conditions in nearly 100 countries and territories worldwide in 2020. WORLD REPORT It reflects extensive investigative work that Human Rights Watch staff conducted during the year, often in close partnership with 2021 domestic human rights activists. EVENTS OF 2020 Human Rights Watch defends HUMAN the rights of people worldwide. RIGHTS WATCH We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch Human Rights Watch began in 1978 with the founding of its Europe and All rights reserved. Central Asia division (then known as Helsinki Watch). Today it also Printed in the United States of America includes divisions covering Africa, the Americas, Asia, Europe and Central ISBN is 978-1-64421-028-4 Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, and the United States. There are thematic divisions or programs on arms; business and human rights; Cover photo: Kai Ayden, age 7, marches in a protest against police brutality in Atlanta, children’s rights; crisis and conflict; disability rights; the environment and Georgia on May 31, 2020 following the death human rights; international justice; lesbian, gay, bisexual, and of George Floyd in police custody. transgender rights; refugee rights; and women’s rights. -

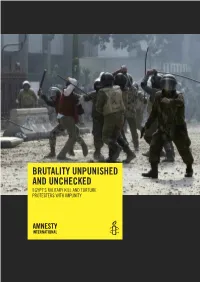

Brutality Unpunished and Unchecked

brutality unpunished and unchecked EGYPT’S MILITARY KILL AND TORTURE PROTESTERS WITH IMPUNITY amnesty international is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the universal declaration of human rights and other international human rights standards. we are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2012 by amnesty international ltd peter benenson house 1 easton street london wc1X 0dw united kingdom © amnesty international 2012 index: mde 12/017/2012 english original language: english printed by amnesty international, international secretariat, united kingdom all rights reserved. this publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. the copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. to request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover phot o: egyptian soldiers beating a protester during clashes near the cabinet offices by cairo’s tahrir square on 16 december 2011. © mohammed abed/aFp/getty images amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................5 2. MASPERO PROTESTS: ASSAULT OF COPTS.............................................................11 3. CRACKDOWN ON CABINET OFFICES SIT-IN.............................................................17 4. -

Tests for Egyptian Journalists

Tests for Egyptian Journalists Reporting Truth, Fighting Censors, Earning a Wage, and Staying Alive in Times of Turmoil By Naomi Sakr n a classic essay in the Journal of Democracy in 2002, “The End of the Transition Paradigm,” democratization analyst Thomas Carothers questioned the assump- Ition that elections are the be-all and end-all of democracy. His argument seems especially apt in Egypt’s case. One mistake, according to Carothers, is to believe that the political and economic effects of decades of dictatorship can be brushed aside. Another is to imagine that state institutions under dictatorship functioned sufficiently well that they can be merely modified and need not be entirely rebuilt. Political scien- tist Sheri Berman, writing in Foreign Affairs in 2013, made similar points about what she called the “pathologies of dictatorship.” These leave a poisonous aftermath of pent-up distrust and animosity, she said, bereft of political bodies capable of respond- ing to or even channeling popular grievances. In Egypt, media institutions, largely controlled by the state since soon after the country became a republic in 1952, are part of this problem, but they can also be part of a future solution. To the extent that news media contribute to framing public discussion, the closer they get to representing the full plurality of interests and viewpoints in society, and the more they report verified information rather than prejudice, rumors, and lies, the more likely it is that different social groups will understand each other and make policy choices that are collectively beneficial. How media pluralism is achieved depends on history. -

Department Ofdefense Office for the Administrative Review of The

UNCLASSIFIED Department of Defense Office for the Administrative Review of the Detention of Enemy Combatants at U.S. Naval Base Guantanamo Bay, Cuba 8 February2007 TO: PersonalRepresentative FROM CSRT ( 8 Feb 07) SUBJECT: SUMMARY OF EVIDENCE FOR COMBATANT REVIEW TRIBUNAL - AL - SHIB, RAMZI BIN Under the provisions of the Deputy Secretary of Defense Memorandum , dated 14 July 2006, Implementation of Combatant Status Review Tribunal Procedures for Enemy Combatants Detained at U.S. Naval Base Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, a Tribunal has been appointed to determine ifthe detainee is an enemy combatant. 2. An enemy combatant has bee defined as an individualwho was part ofor supporting the Taliban or al Qaida forces, or associatedforces that are engaged inhostilitiesagainst the United States or its coalitionpartners. This includes any personwho committeda belligerent act or has directly supported hostilities inaid ofenemy armed forces.” 3. The followingfacts supportthe determinationthat the detaineeisan enemy combatant. a. On the morning of 11 September 2001, four airliners traveling over the United States were hijacked. The flights hijacked were American Airlines Flight 11, United Airlines Flight 175, American Airlines Flight 77 and United Airlines Flight 93. At approximately 8:46 a.m., American Airlines Flight 11 crashed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center, resulting in the collapse of the tower at approximately 10:25 a.m. At approximately 9:03 a.m., United Airlines Flight 175 crashed into the South Tower of the World Trade Center, resulting in the collapse of the tower at approximately 9:55 a.m. At approximately 9:37 a.m., American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the southwest side of the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia. -

The Role of Egyptian Women in the 25Th of January Revolution 2011

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Papers, Posters, and Presentations 2011 The role of Egyptian women in the 25th of January revolution 2011 Dina Shaaban Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/studenttxt Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Shaaban, Dina, "The role of Egyptian women in the 25th of January revolution 2011" (2011). Papers, Posters, and Presentations. 15. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/studenttxt/15 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers, Posters, and Presentations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dina Shaaban 900-98-3959 GWST 501 Dr. Amy Motlagh Spring 2011 Final Paper Role of Egyptian women during the 25th of January revolution Egypt passed though a critical period that changed its future completely. The 25th of January revolution made it possible for Egyptians to call for their rights, defend them and decide on their destiny. Egyptian women are not equally treated as men in the Egyptian society, however they were next to men in Tahrir square calling for freedom and democracy. This revolution witnessed many unique situations, from the huge number of protesters coming out in the streets at the exact same time, to the continuous efforts for making the demonstrations “peaceful”, then the participation of all the nations into the protests no matter their sex, age or background. It was a real “genuine national” revolution, in the sense that every person holding the Egyptian nationality was involved to demand for his/her basic rights. -

STIFLING the PUBLIC SPHERE: MEDIA and CIVIL SOCIETY in EGYPT Sherif Mansour

Media and Civil Society in Egypt STIFLING THE PUBLIC SPHERE: MEDIA AND CIVIL SOCIETY IN EGYPT Sherif Mansour I. Overview More than four years after the dramatic events in Cairo’s Tahrir Square led to the resignation of President Hosni Mubarak and Egypt’s first-ever democratic elections, Egyptian civil society and independent media are once again struggling under military oppression. The July 2013 military takeover led by then-general, now- president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has brought Egypt’s brief, imperfect political opening to an end. The Sisi regime’s goal is to return Egypt to the pre–Arab Spring status quo by restoring the state’s control over the public sphere. To this end, it is tightening the screws on civil society and reversing hard-won gains in press freedom. Civil society activists have been imprisoned, driven underground, or forced into exile. The sorts of lively conversations and fierce debates that were possible before the military takeover were pushed off the airwaves and the front pages, and even online refuges for free discussion are being closed through the use of surveillance and Internet trolls. Egypt’s uneven trajectory over the past several years is reflected in the rankings it has received from Freedom House’s Freedom of the Press report, which downgraded Egypt to Not Free in its 2011 edition, covering events in 2010. After the revolution in early 2011, Egypt improved to Partly Free. By the 2013 edition, it was Not Free once again. And this year, Egypt sunk to its worst press freedom score since 2004.