UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring/Summer 2018

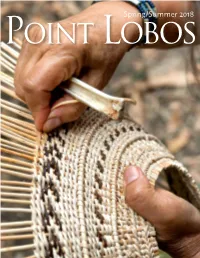

Spring/Summer 2018 Point Lobos Board of Directors Sue Addleman | Docent Administrator Kit Armstrong | President Chris Balog Jacolyn Harmer Ben Heinrich | Vice President Karen Hewitt Loren Hughes Diana Nichols Julie Oswald Ken Ruggerio Jim Rurka Joe Vargo | Secretary John Thibeau | Treasurer Cynthia Vernon California State Parks Liaison Sean James | [email protected] A team of State Parks staff, Point Lobos Docents and community volunteers take a much-needed break after Executive Director restoring coastal bluff habitat along the South Shore. Anna Patterson | [email protected] Development Coordinator President’s message 3 Tracy Gillette Ricci | [email protected] Kit Armstrong Docent Coordinator and School Group Coordinator In their footsteps 4 Melissa Gobell | [email protected] Linda Yamane Finance Specialist Shell of ages 7 Karen Cowdrey | [email protected] Rae Schwaderer ‘iim ‘aa ‘ishxenta, makk rukk 9 Point Lobos Magazine Editor Reg Henry | [email protected] Louis Trevino Native plants and their uses 13 Front Cover Chuck Bancroft Linda Yamane weaves a twined work basket of local native plant materials. This bottomless basket sits on the rim of a From the editor 15 shallow stone mortar, most often attached to the rim with tar. Reg Henry Photo: Neil Bennet. Notes from the docent log 16 Photo Spread, pages 10-11 Compiled by Ruthann Donahue Illustration of Rumsen life by Linda Yamane. Acknowledgements 18 Memorials, tributes and grants Crossword 20 Ann Pendleton Our mission is to protect and nurture Point Lobos State Natural Reserve, to educate and inspire visitors to preserve its unique natural and cultural resources, and to strengthen the network of Carmel Area State Parks. -

Founding Membership List

Founding Members of the Guardians of Culture Membership Group Institutions and Affiliated Organizations Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians Alaska Native Language Archive Alcatraz Cruises Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association, Inc. ASU American Indian Policy Institute Audrey and Harry Hawthorn Library and Archives, UBC Museum of Anthropology Barona Cultural Center & Museum Caddo Heritage Museum Cheyenne & Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma Chickasaw Nation Cultural Center Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation Dine College Dr. Fernando Escalante Community Library & Resource Center Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria George W. Brown Jr. Ojibwe Museum and Cultural Center Hopi Tutuquyki Sikisve Huna Heritage Foundation International Buddhist Ethics Committee & Buddhist Tribunal on Human Rights Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma John G. Neihardt State Historic Site KCS Solutions, Inc. Maitreya Buddhist University Midwest Art Conservation Center Muckleshoot Indian Tribe Museo + Archivio, Inc. Museum Association of Arizona National Museum of the American Indian Newberry Library Noksi Press Osage Tribal Museum Papahana Kuaola Pawnee Nation College Pechanga Cultural Resources Department Poarch Creek Indians Quatrefoil Associates Chippewas of Rama First Nation Southern Ute Cultural Center and Museum Southwestern Indian Polytechnic Institute Speaking Place Tantaquidgeon Museum The Archives of Traditional Music, Indiana University The Autry National Center of the American West The -

Sec 05 11 Tribal and Cultural Resources

Tribal and Cultural Resources 5.11 TRIBAL AND CULTURAL RESOURCES 5.11.1 PURPOSE This section identifies existing cultural (including historic and archeological resources), paleontological and tribal resources within the Study Area, and provides an analysis of potential impacts associated with implementation of the General Plan Update. Potential impacts are identified and mitigation measures to address potentially significant impacts are recommended, as necessary. This section is primarily based upon the Cultural and Tribal Cultural Resources Technical Report for the Rancho Santa Margarita General Plan Update, Rancho Santa Margarita, Orange County, California (Cultural Study), and the Paleontological Resources Impact Assessment Report for the Rancho Santa Margarita General Plan Update, Orange County, California (Paleontological Assessment), both prepared by SWCA Environmental Consultants (SWCA) and dated April 2019; refer to Appendix F, Cultural/ Paleontological Resources Assessment. 5.11.2 EXISTING REGULATORY SETTING Numerous laws and regulations require Federal, State, and local agencies to consider the effects a project may have on cultural resources. These laws and regulations establish a process for compliance, define the responsibilities of the various agencies proposing the action, and prescribe the relationship among other involved agencies (i.e., State Historic Preservation Office and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation). The National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) of 1966, as amended, the California Environmental -

Natural History Museum Unveils Portrait of Juana María, the Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island

Media Contact: Briana Sapp Tivey Director of Marketing and Communications Email: [email protected] Phone: 805-682-4711 ext. 117 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Natural History Museum Unveils Portrait of Juana María, the Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island Local Artist Holli Harmon Creates Likeness Based on First-Hand Accounts Santa Barbara, California (February 21, 2018) — The Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History recently unveiled a historically accurate portrait of Juana María, the Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island. Fictionalized as “Karana” in Scott O’Dell’s novel Island of the Blue Dolphins, she was a real person who lived by herself on San Nicolas Island. Accidentally left behind in 1835, when the last of the native inhabitants were conveyed to the mainland at the request of the Santa Barbara Mission priests, she resourcefully caught her own food, made her own clothes, and built her own shelter for 18 years. In 1853, Carl Dittman and sea otter hunter Captain George Nidever found the woman alive and well. She willingly returned to the mainland on his ship, living with Nidever’s family in Santa Barbara for only seven weeks before she tragically fell ill and died. The Lone Woman was conditionally baptized with the name Juana María and buried at the Santa Barbara Mission. Harmon’s piece is the first painting to be based on historical records. Most representations of Juana María to date have been based on the romantic image popularized in O’Dell’s book. A research team including archaeologist Steve Schwartz, historian Susan Morris, and Museum Curator of Anthropology John Johnson supplied local artist Holli Harmon with historically accurate descriptions of the Lone Woman. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Ancient Plant Use and the Importance of Geophytes Among the Island Chumash of Santa Cruz

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Ancient Plant Use and the Importance of Geophytes among the Island Chumash of Santa Cruz Island, California A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Kristina Marie Gill Committee in charge: Professor Michael A. Glassow, Chair Professor Michael A. Jochim Professor Amber M. VanDerwarker Professor Lynn H. Gamble September 2015 The dissertation of Kristina Marie Gill is approved. __________________________________________ Michael A. Jochim __________________________________________ Amber M. VanDerwarker __________________________________________ Lynn H. Gamble __________________________________________ Michael A. Glassow, Committee Chair July 2015 Ancient Plant Use and the Importance of Geophytes among the Island Chumash of Santa Cruz Island, California Copyright © 2015 By Kristina Marie Gill iii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my Family, Mike Glassow, and the Chumash People. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to many people who have provided guidance, encouragement, and support in my career as an archaeologist, and especially through my undergraduate and graduate studies. For those of whom I am unable to personally thank here, know that I deeply appreciate your support. First and foremost, I want to thank my chair Michael Glassow for his patience, enthusiasm, and encouragement during all aspects of this daunting project. I am also truly grateful to have had the opportunity to know, learn from, and work with my other committee members, Mike Jochim, Amber VanDerwarker, and Lynn Gamble. I cherish my various field experiences with them all on the Channel Islands and especially in southern Germany with Mike Jochim, whose worldly perspective I value deeply. I also thank Terry Jones, who provided me many undergraduate opportunities in California archaeology and encouraged me to attend a field school on San Clemente Island with Mark Raab and Andy Yatsko, an experience that left me captivated with the islands and their history. -

The Carmel Pine Cone

VolumeThe 105 No. 42 Carmelwww.carmelpinecone.com Pine ConeOctober 18-24, 2019 T RUS T ED BY LOCALS AND LOVED BY VISI T ORS SINCE 1 9 1 5 Deal pending for Esselen tribe to buy ranch Cal Am takeover By CHRIS COUNTS But the takeover is not a done deal yet, despite local media reports to the contrary, Peter Colby of the Western study to be IF ALL goes according to plan, it won’t be a Silicon Rivers Conservancy told The Pine Cone this week. His Valley executive or a land conservation group that soon group is brokering the deal between the current owner of takes ownership of a remote 1,200-acre ranch in Big Sur the ranch, the Adler family of Sweden, and the Esselen released Nov. 6 but a Native American tribe with deep local roots. Tribe of Monterey County. “A contract for the sale is in place, By KELLY NIX but a number of steps need to be com- pleted first before the land is trans- THE LONG-AWAITED findings of a study to deter- ferred,” Colby said. mine the feasibility of taking over California American While Colby didn’t say how much Water’s local system and turning it into a government-run the land is selling for, it was listed operation will be released Nov. 6, the Monterey Peninsula at $8 million when The Pine Cone Water Management District announced this week. reported about it in 2017. But ear- The analysis was launched after voters in November lier this month, the California Nat- 2018 OK’d a ballot measure calling for the water district ural Resources Agency announced to use eminent domain, if necessary, to acquire Cal Am’s that something called “the Esselen Monterey Peninsula water system if the move was found Tribal Lands Conservation Project” to be cost effective. -

Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo

PACIFYING PARADISE: VIOLENCE AND VIGILANTISM IN SAN LUIS OBISPO A Thesis presented to the Faculty of California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History by Joseph Hall-Patton June 2016 ii © 2016 Joseph Hall-Patton ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP TITLE: Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo AUTHOR: Joseph Hall-Patton DATE SUBMITTED: June 2016 COMMITTEE CHAIR: James Tejani, Ph.D. Associate Professor of History COMMITTEE MEMBER: Kathleen Murphy, Ph.D. Associate Professor of History COMMITTEE MEMBER: Kathleen Cairns, Ph.D. Lecturer of History iv ABSTRACT Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo Joseph Hall-Patton San Luis Obispo, California was a violent place in the 1850s with numerous murders and lynchings in staggering proportions. This thesis studies the rise of violence in SLO, its causation, and effects. The vigilance committee of 1858 represents the culmination of the violence that came from sweeping changes in the region, stemming from its earliest conquest by the Spanish. The mounting violence built upon itself as extensive changes took place. These changes include the conquest of California, from the Spanish mission period, Mexican and Alvarado revolutions, Mexican-American War, and the Gold Rush. The history of the county is explored until 1863 to garner an understanding of the borderlands violence therein. v TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………... 1 PART I - CAUSATION…………………………………………………… 12 HISTORIOGRAPHY……………………………………………........ 12 BEFORE CONQUEST………………………………………..…….. 21 WAR……………………………………………………………..……. 36 GOLD RUSH……………………………………………………..….. 42 LACK OF LAW…………………………………………………….…. 45 RACIAL DISTRUST………………………………………………..... 50 OUTSIDE INFLUENCE………………………………………………58 LOCAL CRIME………………………………………………………..67 CONCLUSION………………………………………………………. -

Archdiocese of Los Angeles Catholic Directory 2020-2021

ARCHDIOCESE OF LOS ANGELES CATHOLIC DIRECTORY 2020-2021 Mission Basilica San Buenaventura, Ventura See inside front cover 01-FRONT_COVER.indd 1 9/16/2020 3:47:17 PM Los Angeles Archdiocesan Catholic Directory Archdiocese of Los Angeles 3424 Wilshire Boulevard Los Angeles, CA 90010-2241 2020-21 Order your copies of the new 2020-2021 Archdiocese of Los Angeles Catholic Directory. The print edition of the award-winning Directory celebrates Mission San Buenaventura named by Pope Francis as the first basilica in the Archdiocese. This spiral-bound, 272-page Directory includes Sept. 1, 2020 assignments – along with photos of the new priests and deacons serving the largest Archdiocese in the United States! The price of the 2020-21 edition is $30.00 (shipping included). Please return your order with payment to assure processing. (As always, advertisers receive one complimentary copy, so consider advertising in next year’s edition.) Directories are scheduled to begin being mailed in October. _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Please return this portion with your payment REG Archdiocese of Los Angeles 2020-2021 LOS ANGELES CATHOLIC DIRECTORY ORDER FORM YES, send the print version of the 2020-21 ARCHDIOCESE OF LOS ANGELES CATHOLIC DIRECTORY at the flat rate of $30.00 each. Please return your order with payment to assure processing. -

Native Sustainment: the North Fork Mono Tribe's

Native Sustainment The North Fork Mono Tribe's Stories, History, and Teaching of Its Land and Water Tenure in 1918 and 2009 Jared Dahl Aldern Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy from Prescott College in Education with a Concentration in Sustainability Education May 2010 Steven J. Crum, Ph.D. George Lipsitz, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member Margaret Field, Ph.D. Theresa Gregor, Ph.D. External Expert Reader External Expert Reader Pramod Parajuli, Ph.D. Committee Chair Native Sustainment ii Copyright © 2010 by Jared Dahl Aldern. All rights reserved. No part of this dissertation may be used, reproduced, stored, recorded, or transmitted in any form or manner whatsoever without written permission from the copyright holder or his agent(s), except in the case of brief quotations embodied in the papers of students, and in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Requests for such permission should be addressed to: Jared Dahl Aldern 2658 East Alluvial Avenue, #103 Clovis, CA 93611 Native Sustainment iii Acknowledgments Gratitude to: The North Fork Mono Tribe, its Chairman, Ron Goode, and members Melvin Carmen (R.I.P.), Lois Conner, Stan Dandy, Richard Lavelle, Ruby Pomona, and Grace Tex for their support, kindnesses, and teachings. My doctoral committee: Steven J. Crum, Margaret Field, Theresa Gregor, George Lipsitz, and Pramod Parajuli for listening, for reading, and for their mentorship. Jagannath Adhikari, Kat Anderson, Steve Archer, Donna Begay, Lisa -

Native American Heritage Commission 40Th Anniversary Gala

“Itu ~(/; W/is ~the ~policy 4of ~the ~state Uwd/;that Native~ Americansll/~ remains ~ ~~~~JwJU~~JJand associated grave goods shall be repatriated.” - California Public Resources Code 5097.991 Table of Contents Event Agenda ....................................................................................................................1 Welcome Letter – Governor Edmund G. Brown Jr. ...........................................................2 2016 Native American Day Proclamation ...........................................................................3 Welcome Letter – NAHC Chairperson James Ramos ...................................................... 4 Welcome Letter – NAHC Executive Secretary Cynthia Gomez .........................................5 Keynote Speaker Biography ............................................................................................6 State Capitol Rotunda Displays .......................................................................................7 Native American Heritage Commission’s Mission Statement .............................................8 Tribal People of California Map .......................................................................................13 California Indian Seal ...................................................................................................... 14 The Eighteen Unratifed Treaties of 1851-1852 between the California Indians and the United States Government .................................................................................15 NAHC Timeline -

1. Introduction

1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Ethnographic setting The Chimariko language was spoken in the nineteenth century in a few small villages in Trinity County, in north-western California. The villages were located along a twenty-mile stretch of the Trinity River and parts of the New River and South Fork River. In 1849, the Chimariko numbered around two hundred and fifty people. They were nearly extinct in 1906, except for a ‘toothless old woman and a crazy old man’, as well as ‘a few mixed bloods’ (Kroeber 1925:109). The ‘toothless old woman’ Kroeber refers to was most likely Polly Dyer and the ‘crazy old man’ Dr. Tom, also identified by Dixon (1910:295) as a ‘half-crazy old man’. The last speaker probably died in the 1940s. First contact with European explorers occurred early in the nineteenth century, in the 1820s or 1830s, when fur trappers came to the region. However, the tribe was left largely unaffected by this encounter (Dixon 1910:297). During the Gold Rush in the 1850s the Chimariko territory was overrun by gold seekers. Continuous gold mining activities in the region threatened the salmon supply, the main food source of the tribe, and led to a bitter conflict in the 1860s (Silver 1978a:205). The fights between European miners and the tribe resulted in the near annihilation of the Chimariko in the 1860s. The few survivors took refuge with the neighboring Shasta on the upper Salmon River or in Scott Valley or with the Hupa to the northwest (Dixon 1910:297). Once the gold was gone and the miners left the region, the survivors returned to their homes after years in exile (Silver 1978a:205). -

The Desert Serrano of the Mojave River

The Desert Serrano of the Mojave River Mark Q. Sutton and David D. Earle Abstract century, although he noted the possible survival of The Desert Serrano of the Mojave River, little documented by “perhaps a few individuals merged among other twentieth century ethnographers, are investigated here to help un- groups” (Kroeber 1925:614). In fact, while occupation derstand their relationship with the larger and better known Moun- tain Serrano sociopolitical entity and to illuminate their unique of the Mojave River region by territorially based clan adaptation to the Mojave River and surrounding areas. In this effort communities of the Desert Serrano had ceased before new interpretations of recent and older data sets are employed. 1850, there were survivors of this group who had Kroeber proposed linguistic and cultural relationships between the been born in the desert still living at the close of the inhabitants of the Mojave River, whom he called the Vanyumé, and the Mountain Serrano living along the southern edge of the Mojave nineteenth century, as was later reported by Kroeber Desert, but the nature of those relationships was unclear. New (1959:299; also see Earle 2005:24–26). evidence on the political geography and social organization of this riverine group clarifies that they and the Mountain Serrano belonged to the same ethnic group, although the adaptation of the Desert For these reasons we attempt an “ethnography” of the Serrano was focused on riverine and desert resources. Unlike the Desert Serrano living along the Mojave River so that Mountain Serrano, the Desert Serrano participated in the exchange their place in the cultural milieu of southern Califor- system between California and the Southwest that passed through the territory of the Mojave on the Colorado River and cooperated nia can be better understood and appreciated.