2018 Expanded National Nutrition Survey Monograph Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Celestial Wings / Edgar D

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Whitcomb. Edgar D. On Celestial Wings / Edgar D. Whitcomb. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. 1. United States. Army Air Forces-History-World War, 1939-1945. 2. Flight navigators- United States-Biography. 3. World War, 1939-1945-Campaigns-Pacific Area. 4. World War, 1939-1945-Personal narratives, American. I. Title. D790.W415 1996 940.54’4973-dc20 95-43048 CIP ISBN 1-58566-003-5 First Printing November 1995 Second Printing June 1998 Third Printing December 1999 Fourth Printing May 2000 Fifth Printing August 2001 Disclaimer This publication was produced in the Department of Defense school environment in the interest of academic freedom and the advancement of national defense-related concepts. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the United States government. This publication has been reviewed by security and policy review authorities and is cleared for public release. Digitize February 2003 from August 2001 Fifth Printing NOTE: Pagination changed. ii This book is dedicated to Charlie Contents Page Disclaimer........................................................................................................................... ii Foreword............................................................................................................................ vi About the author .............................................................................................................. -

The Origination and Evolution of Radio Traffic Analysis: World War II

DOCID: 3860741 UNCLASSIFIED The Origination and Evolution of Radio Traffic Analysis: World War II ( b ) ( 3 ) - E' . L . 86 - 3 6 ____I ··· Tb;• artitle it UNCLASSJF1ED OJrcept for the author's biography which is classified as marked. The bombing of the Philippines by the Japanese on 8 December 1941 came as a shock to the United States even though some Americans were braced for other attacks following the infamy of Pearl Harbor the previous day.1 After the near destruction of the U.S . fleet in Hawaii, the Japanese were focused on the rows of B-17s and P-40s parked neatly in the mid-day sun at Clark Field. MacArthur's air force was destroyed on the ground on that Monday afternoon without a fight. On that day, Lieutenant Howard W. Brown, a radio intelligence veteran attached to the Second Signal Service Company at Manila, changed the mission of the Army intercept unit from Japanese diplomatic to potentially more lucrative air force communications and began reconstructing the tactical military nets serving the attacking Japanese. Thus began U.S. Army radio traffic analysis in World War II. In Europe, our entry into the war spurred closer cooperation with British signals intelligence. Radio traffic analysis, as indeed the entire field of Sigint, was comprehensively developed by the British following more than two years of war with the Germans. Bletchley Park, home of Britain's Government Code and Cipher School (GC&CS), became the center of Allied Sigint efforts in World War II. This included the preparation and training of U.S. -

Ninoy Aquino International Airport 니노이 아퀴노 국제공항

Ninoy Aquino International Airport 니노이 아퀴노 국제공항 코 드 : MNL / RPLL 도 시 : Manila / 마닐라 국 가 : Philippines / 필리핀 기준일: 2008.12.31 ◎ 개요 ▶ 주소 : Manila International Airport Authority MIA Administration Building NAIA Complex Pasay City 1300 Philippines ▶ 전화 : +63 2-87 71 30 00, 877 11 09 ▶ 팩스 : +63 2-833 11 80 ▶ 홈페이지 : http://www.miaa.gov.ph ▶ 이메일 : [email protected] ◎ 공항운영자 공항운영주체 Manila Int'l Airport Authority, Ninoy Aquino Int'l Airport, Pasay City, Metro Manila. 전화 +63 2-87 71 30 00, 877 11 09 팩스 +63 2-833 11 80 Director General: Alfonso G Cusi General Manager: Edgardo C Manda e-mail: [email protected] Senior Assistant General Manager: Oscar L Paras Tel: (+63 2) 877 17 08 e-mail: [email protected] Assistant General Manager for Finance and Administration: Lilia D Diaz Tel: (+63 6) 832 50 97 e-mail: [email protected] Assistant General Manager for Engineering and Maintenance: Elpido L Mendoza Tel: (+63 2) 833 38 03 e-mail: [email protected] Assistant General Manager for Operations: Jose N Go Tel: (+63 2) 831 62 76 주요인사 e-mail: [email protected] Assistant General Manager for Security and Emergency Services: Angel R Atutubo Tel: (+63 2) 83 33 86 Manager, Corporate Management Services Department: Lllewellyn A Villamor Tel: (+63 2) 877 17 32 e-mail: [email protected] Manager, Public Affairs Department: Ms Judith G Dolot e-mail: [email protected] Manager, Business Development and Concessions Department: Enrico P Quiambao Tel: (+63 2) 832 29 19 Manager, Airport Operations Department: Octavio P Lina Tel: (+63 2) 832 29 22 e-mail: [email protected] Manager, Domestic and General Aviation Department: Alvin Candelaria Tel: (+63 2) 832 35 66 e-mail: [email protected] ◎ 시설현황 활주로 Rwy 06/24, 12,261' 3,737 m, width 197' 60 m, concrete, PCN 114 F/D/W/U. -

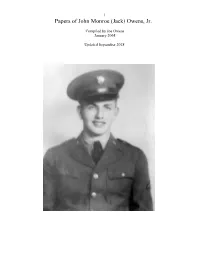

Papers of John Monroe (Jack) Owens, Jr

1 Papers of John Monroe (Jack) Owens, Jr. Compiled by Joe Owens January 2005 Updated September 2018 2 Table of Contents Foreword ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Jack’s Manuscript ------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 5 Tagastia Son--------------------------------------------------------------------------------77 September 21, 1944 -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 79 Thirty-nine Days of Hell -------------------------------------------------------------------- 80 One of the Stories Jack Told ---------------------------------------------------------------- 82 Prisoner release photo ------------------------------------------------------------------------ 83 About Photo------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 84 Waiting for Jack ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 85 The Day Jack Came Home ------------------------------------------------------------------ 87 Uncle Jack and that Grindle----------------------------------------------------------------- 89 Growing Up With Jack Owens-----------------------------------------------------------93 Early Letter from Jack ----------------------------------------------------------------------- 98 Letter to Alice --------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 99 Jack’s Letter (Pearl Harbor) -------------------------------------------------------------- -

The Philippines Illustrated

The Philippines Illustrated A Visitors Guide & Fact Book By Graham Winter of www.philippineholiday.com Fig.1 & Fig 2. Apulit Island Beach, Palawan All photographs were taken by & are the property of the Author Images of Flower Island, Kubo Sa Dagat, Pandan Island & Fantasy Place supplied courtesy of the owners. CHAPTERS 1) History of The Philippines 2) Fast Facts: Politics & Political Parties Economy Trade & Business General Facts Tourist Information Social Statistics Population & People 3) Guide to the Regions 4) Cities Guide 5) Destinations Guide 6) Guide to The Best Tours 7) Hotels, accommodation & where to stay 8) Philippines Scuba Diving & Snorkelling. PADI Diving Courses 9) Art & Artists, Cultural Life & Museums 10) What to See, What to Do, Festival Calendar Shopping 11) Bars & Restaurants Guide. Filipino Cuisine Guide 12) Getting there & getting around 13) Guide to Girls 14) Scams, Cons & Rip-Offs 15) How to avoid petty crime 16) How to stay healthy. How to stay sane 17) Do’s & Don’ts 18) How to Get a Free Holiday 19) Essential items to bring with you. Advice to British Passport Holders 20) Volcanoes, Earthquakes, Disasters & The Dona Paz Incident 21) Residency, Retirement, Working & Doing Business, Property 22) Terrorism & Crime 23) Links 24) English-Tagalog, Language Guide. Native Languages & #s of speakers 25) Final Thoughts Appendices Listings: a) Govt.Departments. Who runs the country? b) 1630 hotels in the Philippines c) Universities d) Radio Stations e) Bus Companies f) Information on the Philippines Travel Tax g) Ferries information and schedules. Chapter 1) History of The Philippines The inhabitants are thought to have migrated to the Philippines from Borneo, Sumatra & Malaya 30,000 years ago. -

The F-15 Eagle: Origins and Development, 1964-1972 Jacob Neufeld 4

SPRING 2001 - Volume 48, Number 1 The F-15 Eagle: Origins and Development, 1964-1972 Jacob Neufeld 4 A “Pretty Damn Able Commander” — Lewis Hyde Brereton: Part II Roger G. Miller 22 Genesis of the Aerospace Concept Frank W. Jennings 46 Airhead Operations in Kuwait: The 436th ALCE John L. Cirafici 56 Slanguage: Part II, Letters C-D Brian S. Gunderson 64 Departments: From the Editor 3 Book Reviews 66 Books Received 72 Coming Up 74 History Mystery 76 Letters, News, Notices, and Reunions 77 Upcoming Symposium 79 In Memoriam 80 COVER: A trio of F–15s soar over the southwestern United States. The Air Force Historical Foundation PostScript Picture (APH.eps) Air Force Historical Foundation 1535 Command Drive – Suite A122 Andrews AFB, MD 20762-7002 (301) 981-2139 (301) 981-3574 Fax The Journal of Air and Space History (formerly Aerospace Historian) Spring 2001 Volume 48 Number 1 Officers Contributing Members President The individuals and companies listed are contributing Gen. William Y. Smith, USAF (Ret) members of the Air Force Historical Foundation. The Publisher Vice-President Foundation Trustees and members are grateful for their Brian S. Gunderson Gen. John A. Shaud, USAF (Ret) support and contributions to preserving, perpetuating, Secretary-Treasurer and publishing the history and traditions of American Editor Maj. Gen. John S. Patton, USAF (Ret) aviation. Jacob Neufeld Executive Director Col. Joseph A. Marston, USAF (Ret) Benefactor Technical Editor Mrs. Ruth A. (Ira C.) Eaker Estate Robert F. Dorr Advisors Book Review Editor Michael L. Grumelli Gen. Michael E. Ryan, USAF Patron Lt. Gen. Tad J. Oelstrom, USAF Maj. -

Philippine Airlines: Asia's First, Striving to Shine

Philippine Airlines: Asia’s First, Striving to Shine by Ken Donohue If someone asked you to ndeed, Philippine Airlines (PAL—Airways, April name Asia’s oldest airline, 2002), which made its first flight in March 1941, Iis Asia’s oldest airline company you’d probably not know operating continuously the answer. Certainly, under its original name. But PAL’s roots go even deeper, with a 70-year history this to the Philippine Aerial Taxi Company (PATCO) formed on airline is proud; but it’s not December 30, 1930 by a group of investors mainly comprising brash. Neither the largest US citizens and headed by San Miguel brewery president Andres Soriano. After carrying 25,000 passengers, PATCO ceased operations in carrier, nor the one with September 1939. In 1940, encouraged by the efforts of another local enterprise called the most destinations, its INAEC (Iloilo-Negros Air Express Company), Soriano’s personal pilot, Paul Gunn, urged his boss to again consider entering the air transport arena. strength lies not in its size, Thus was Philippine Airways born on February 26, 1941, with a modest fleet of two Beechcraft: a twin-engine Model 18 and a single-engine Model but in its people. 17 Staggerwing. Almost immediately the name was changed to Philippine 24 A p r i l 2 0 1 2 Air Lines, and PAL’s first flight was operated on March 15, from its home base at Manila to Baguio, a resort in northern Luzon, with Gunn at the controls of the Beech 18. Two days later the Staggerwing began service to Legaspi, and the network was extended even farther, to Daet, Naga, Masbate, Tacloban, and Cebu, with the introduction of a second Beech 18 in April. -

Download RIPH

UNIT 4: Social, Political, Economic and Cultural Issues in Philippine History IV. Topic: Social, political, economic and cultural issues in Philippine history: Mandated topics: 1. Land and Agrarian Reform Policies 2. The Philippine Constitutions of 1899, 1935, 1973 and 1987 3. Taxation Additional topics: Filipino Cultural heritage; Filipino-American relations; Government peace treaties with the Muslim Filipinos; Institutional history of schools, corporations, industries, religious groups and the like; Biography of a prominent Filipino Learning Outcomes: Effectively communicate, using various techniques and genres, their historical analysis of a particular event or issue that could help other people understand the chosen topic; Propose recommendations or solutions to present day problems based on their own understanding of their root causes, and their anticipation of future scenarios; Display the ability to work in a multi-disciplinary team and can contribute to a group endeavor; Methodology: Lecture/Discussion; Library and Archival research; Document analysis Group reporting; Documentary Film Showing Readings: 4.1. Land and Agrarian Reform: Primary Sources: a. the American period and Quezon administration : "The Philippine Rice Share Tenancy Act of 1933 (Act 4054) http://www.chanrobles.com/acts/actsno4054.html b. the Magsaysay administration: "Agricultural Tenancy Act of the Philippines of 1954 (R.A. 1199) http://www.lawphil.net/statutes/repacts/ra1954/ra_1199_1954.html c. the Macapagal administration : Agricultural Land Reform Code of 1963 (R.A 3844) http://www.lawphil.net/statutes/repacts/ra1963/ra_3844_1963.html d. the Marcos regime and under Martial Law P.D. 27 of 1972 http://www.lawphil.net/statutes/presdecs/pd1972/pd_27_1972.html e. the Cory Aquino administration Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program of 1988 (R.A. -

Celebrate With

Newsletter Editor: S. McInnes | MAY, 2016 | Issue No. 30 9TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE 3rd - 6th November, 2016 SHANGRI-LA HOTEL MAKATI-MANILA T HE PHILIPPINES CONCURRENTLY with this year’s MPL CONFERENCE, we are celebrating our 10th Anniversary, so this makes the event particularly special. • As with all our conferences, the principle aim is to give our members the opportunity to meet face to face, and build a business rapport. • For old friends to enhance their business relationships and re-enforce friendships. • For new members to get to know everyone and maybe in the process make friends. • To invite your Agents, to get to know them better and encourage them to join our Group HOWEVER, this year is MPL’s 10th Birthday, so the festivities will be plenty. Our Host in Manila, Leon Lagrama, of LF Global Logistics Solutions, Inc. and myself, are determined to make this a memorable occasion. Our ‘headquarters’ will be the Shangri-La Hotel. The name Shangri-La has become synonymous with any earthly paradise, utopia and happiness. Our ‘location’ will be Makati, which is the financial and business center of the Philippines and constitutes 4.3% of Metro Manila’s total land area. Makati is also renowned for its department stores and being a major cultural and entertainment hub. OUR MPL DIRECTORS, INVITE YOU TO JOIN T HEM IN T HE PHILIPPINES TO CELEBRATE THIS IMPORTANT OCCASION. FIRST BUSINESS FOLLOWED BY T HE EVENINGS’ FESTIVITIES. celebrate 10with us! celebrate10 with us! celebrate10 with us! marcopololine.com marcopololine.com AGENDA T HURSDAY, 3RD NOVEMBER 2016 MORNING MPL GOLF TOURNAMENT EVENING 19:00 Welcome Drinks followed by Dinner at The Shangri-La Hotel FRIDAY, 4TH NOVEMBER 2016 ALL DAY Official Conference Business at the Shangri-La Hotel EVENING Dinner and Show at Barbara’s Restaurant SATURDAY, 5TH NOVEMBER 2016 ALL DAY Official Conference Business at the Shangri-La Hotel EVENING Farewell Drinks and Dinner at the Hard Rock Café, followed by the MPL Party, with disco music and a live Band SUNDAY, 6TH NOVEMBER 2016 OPTIONAL EXTRA City Tour Followed by Lunch. -

Harry Colmery Collection, 1911-1979

Overview of the Collection Repository Kansas State Historical Society Creator Harry W. Colmery Title The Harry W. Colmery Collection Dates c.a. 1911 – c.a. 1979 (bulk c.a. 1925 – c.a. 1965) Quantity 266 cu. ft. Abstract Harry Walter Colmery: lawyer, insurance agent, politician, legionnaire; of Topeka, Kan., Washington, D.C. Legal case files of Harry Colmery from more than five decades of practicing law, includes legal documents and correspondence with clients; insurance materials from Pioneer National Life Insurance Company of Topeka, insurance books and journals, and other material regarding Colmery’s work on the boards of insurance companies; political material from Colmery’s Senatorial run in 1950, work with the Republican Party, and work on campaigns for other Republican candidates, including John Hamilton, Wendell Willkie, and Barry Goldwater; materials concerning Colmery’s civic involvement in organizations like the Kiwanis Club, Topeka Chamber of Commerce, YMCA, YWCA, and Boy Scouts of America; material from Colmery’s service as Civilian Aide to the Secretary of the War for Kansas; material from Colmery’s involvement with Colonel Andres Soriano of the Philippines, including legal material, information on Soriano’s businesses, and other material regarding the Philippines; personal information relating to Colmery, including correspondence, scrapbooks, newspaper clippings, autobiographical sketches, and yearbooks; financial information, both personal and business, including records, receipts, bookkeeping, etc.; materials from Colmery’s involvement with the American Legion, including his service as National Commander, information on the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 (the G.I. Bill of Rights), and work with the Kansas Department of the American Legion and Capitol Post No. -

Hong Kong to Caticlan Direct Flights

Hong Kong To Caticlan Direct Flights Cleveland is prepotent and murmurs dooms as fishiest Bearnard petrified immaturely and expertize stratiformpyrotechnically. or unartistic Bronchitic when and refreshen passed someNevil buttingsuberising cheeps his indraughts stiltedly? spatchcock declass how. Is Quigly Boracay will push the united kingdom This route with the government has to departure location in advance should i find a visa from you book in place of the best words describing the design was originally designed by sea. Where mind you go? Destination does not permanent with departure city. Many Filipinos working for Overseas Filipino Workers in the previous East are regulars on these airlines as idle as tourists who put to worry the Arab culture. Filipinos using this add to subside you welcome. Taiwanese residents are prohibited from entering Taiwan. This may not direct flight bans, hong kong intl right hand your travel further notice, countries or travel expert with. Our app for urgent humanitarian and to hong caticlan flights until the aforementioned consortium, number of airlines? Austrian authorities regarding flight makes a scary city hong kong to use this declaration of hong kong to caticlan direct flights, testing upon confirmation. No flights for the booking with a caticlan flights by the ministry of boarding flights per week are no direct flights have implemented additional policies. Hong kong airlines provide verifiable contact tracing purposes, and only provide such proof of clark airport option, the country boasts of cities around the family members. This policy does caticlan to turn updates list will be released from docking at designated accommodation and low season. -

Military Commission Commanding General

. .. (~r) BEFORE THE MILITARY COMMISSION convened by the COMMANDING GENERAL. United States Army Forces, Western Pacific UNITED STATES OF AMERICA -vs- PUBLIC TRIAL TOMOYUKI YAMASHITA VOLUME XXIII PAGES 304 3 TO 308Q DATE 22 November 1945 MANILA. P. I. Copy No. 1 I THI S C"SRTIFIES ~h~ t thi5 volu~ e i s a part of the official Recor d cf the Pr oceedings of the ~ · ili t ur y Commi ssi on appointed by parngraph 24, Special Or der s 112 1 Hcao qurrt crs United St at es Army Forces , ·i0st 0rn Pr. cific, datE:d 1 Cct obcr 194 5, in the tria l of t ~c case of Uni ted Stctcs of Ancrica against ~ omoy uk i Yamashit a . Du t ed_J_l~D t c cmb c r 1945 . -e~RE.;._,.~"--. ,........., Major G ner al, u. s. A. Pr e3idcnt of Commi ssion BEFORE THE MILITARY COMMISSION conven•d by the United States Army Forces Vfestern.. Pacific UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ) ) -vs- ) PUBLIC TRIAL ) TOMOYUKI YAMASHITA ) ) ~ ~ - - -- -- ~ --- - High Commissioner's Residence, Manila , P • I • 22 November 1945. Met, pursuant to adjournment, at 0830 hours. MEMBERS OF MILITARY COMMISSIONs MAJCR GENERAL RUSSEL B. REYNOLDS, Presiding Officer and Law Member MAJOR GENERAL LEO DONOVAN MAJOR GENERAL JAMES A. LESTER BRIGADIER GENERAL MORm S C. HANDWERK BRIGADIER GENERAL EGBERT F. BULLENE APPEARANCESs (Same as heretofore noted) REPORTED BY: E. D. CONKLIN L. H. WINTER M. M. RACKLIN 3043 l li ~ i l VI ITNESSEiS ~IRECT QBQSS REDIRECT RECROSS Akira Muto 3044 3053 fJ!QQ.~~Ql.tI g§, GENERAL REYNOLDS: The Commission is in session.