Download RIPH

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: WAR AND RESISTANCE: THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jon T. Sumida, History Department What happened in the Philippine Islands between the surrender of Allied forces in May 1942 and MacArthur’s return in October 1944? Existing historiography is fragmentary and incomplete. Memoirs suffer from limited points of view and personal biases. No academic study has examined the Filipino resistance with a critical and interdisciplinary approach. No comprehensive narrative has yet captured the fighting by 260,000 guerrillas in 277 units across the archipelago. This dissertation begins with the political, economic, social and cultural history of Philippine guerrilla warfare. The diverse Islands connected only through kinship networks. The Americans reluctantly held the Islands against rising Japanese imperial interests and Filipino desires for independence and social justice. World War II revealed the inadequacy of MacArthur’s plans to defend the Islands. The General tepidly prepared for guerrilla operations while Filipinos spontaneously rose in armed resistance. After his departure, the chaotic mix of guerrilla groups were left on their own to battle the Japanese and each other. While guerrilla leaders vied for local power, several obtained radios to contact MacArthur and his headquarters sent submarine-delivered agents with supplies and radios that tie these groups into a united framework. MacArthur’s promise to return kept the resistance alive and dependent on the United States. The repercussions for social revolution would be fatal but the Filipinos’ shared sacrifice revitalized national consciousness and created a sense of deserved nationhood. The guerrillas played a key role in enabling MacArthur’s return. -

Title <Book Reviews>Lisandro E. Claudio. Taming People's Power: the EDSA Revolutions and Their Contradictions. Quezon City

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository <Book Reviews>Lisandro E. Claudio. Taming People's Power: Title The EDSA Revolutions and Their Contradictions. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2013, 240p. Author(s) Thompson, Mark R. Citation Southeast Asian Studies (2015), 4(3): 611-613 Issue Date 2015-12 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/203088 Right ©Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University Book Reviews 611 correct, and was to prove the undoing of the Yingluck government. Nick Nostitz’s chapter on the redshirt movement provides a useful summary of his views, though there are few surprises for those who follow his regular online commentary pieces on these issues. Andrew Walker’s article “Is Peasant Politics in Thailand Civil?” answers its own question in his second sentence: “No.” He goes on to provide a helpful sketch of the arguments he has made at greater length in his important 2012 book Thailand’s Political Peasants. The book concludes with two chapters ostensibly focused on crises of legitimacy. In his discussion of the bloody Southern border conflict, Marc Askew fails to engage with the arguments of those who see the decade-long violence as a legitimacy crisis for the Thai state, and omits to state his own position on this central debate. He rightly concludes that “the South is still an inse- cure place” (p. 246), but neglects to explain exactly why. Pavin Chachavalpongpun offers a final chapter on Thai-Cambodia relations, but does not add a great deal to his brilliant earlier essay on Preah Vihear as “Temple of Doom,” which remains the seminal account of that tragi-comic inter- state conflict. -

FOI Manuals/Receiving Officers Database

National Government Agencies (NGAs) Name of FOI Receiving Officer and Acronym Agency Office/Unit/Department Address Telephone nos. Email Address FOI Manuals Link Designation G/F DA Bldg. Agriculture and Fisheries 9204080 [email protected] Central Office Information Division (AFID), Elliptical Cheryl C. Suarez (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 2158 [email protected] Road, Diliman, Quezon City [email protected] CAR BPI Complex, Guisad, Baguio City Robert L. Domoguen (074) 422-5795 [email protected] [email protected] (072) 242-1045 888-0341 [email protected] Regional Field Unit I San Fernando City, La Union Gloria C. Parong (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4111 [email protected] (078) 304-0562 [email protected] Regional Field Unit II Tuguegarao City, Cagayan Hector U. Tabbun (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4209 [email protected] [email protected] Berzon Bldg., San Fernando City, (045) 961-1209 961-3472 Regional Field Unit III Felicito B. Espiritu Jr. [email protected] Pampanga (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4309 [email protected] BPI Compound, Visayas Ave., Diliman, (632) 928-6485 [email protected] Regional Field Unit IVA Patria T. Bulanhagui Quezon City (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4429 [email protected] Agricultural Training Institute (ATI) Bldg., (632) 920-2044 Regional Field Unit MIMAROPA Clariza M. San Felipe [email protected] Diliman, Quezon City (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4408 (054) 475-5113 [email protected] Regional Field Unit V San Agustin, Pili, Camarines Sur Emily B. Bordado (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4505 [email protected] (033) 337-9092 [email protected] Regional Field Unit VI Port San Pedro, Iloilo City Juvy S. -

The Sakdal Movement, 1930-34

philippine studies Ateneo de Manila University • Loyola Heights, Quezon City • 1108 Philippines The Sakdal Movement, 1930-34 Motoe Terami-Wada Philippine Studies vol. 36, no. 2 (1988) 131–150 Copyright © Ateneo de Manila University Philippine Studies is published by the Ateneo de Manila University. Contents may not be copied or sent via email or other means to multiple sites and posted to a listserv without the copyright holder’s written permission. Users may download and print articles for individual, noncom- mercial use only. However, unless prior permission has been obtained, you may not download an entire issue of a journal, or download multiple copies of articles. Please contact the publisher for any further use of this work at [email protected]. http://www.philippinestudies.net Fri June 27 13:30:20 2008 The Sakdal Movement, 1930-34 MOTOE TERAMI-WADA INTRODUCTION From the start of the United States occupation of the Philippines, the independence issue was a concern of the majority of the Filipino people. The only difference among them was the time of its realiza- tion. Various groups not only expressed their stand on the issue, but also worked for its implementation through legitimate political means or through radical, and at times violent, means. The most influential and visible group among them was that of the Filipino political leaders of the time, represented by Manuel L. Quezon, Sergio Osmefla, and Manuel Roxas. Other groups were opposed to their methods. One such group was the Sakdal Movement, which was active in Central and Southern Luzon. The Sakdal Movement started in 1930 and lasted for at least fifteen years. -

Applicability of the Bus Rapid Transit System Along Epifanio Delos Santos Avenue

5st ATRANS SYMPOSIUM STUDENT CHAPTER SESSION AUGUST24-25, 2012 BANGKOK THAILAND APPLICABILITY OF THE BUS RAPID TRANSIT SYSTEM ALONG EPIFANIO DELOS SANTOS AVENUE Paper Identification number: SCS12-004 Marcus Kyle BARON1, Caroline ESCOVER2, Mayumi TSUKAMOTO3 1Department of Civil Engineering, College of Engineering De La Salle University - Manila Telephone 02-524-4611 E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Civil Engineering, College of Engineering De La Salle University - Manila Telephone 02-524-4611 E-mail: [email protected] 3Department of Civil Engineering, College of Engineering De La Salle University - Manila Telephone 02-524-4611 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Epifanio delos Santos Avenue (EDSA), the 24-kilometer long prime artery of Metro Manila experiences heavy traffic daily. According to recent studies, 50% excess buses add drastically to the growing number of vehicles passing through EDSA. One way to decongest traffic is to cut through the volume of buses. A Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system can be more effective in improving the service operation of buses rather than implementing more city bus operations. The study presents a proposed BRT system in EDSA. The study evaluates the transportation impact of the BRT system on commuter movement and urban travel, and assesses the environmental benefits of the proposed BRT system. Data used in this study were obtained through vehicle counting, onboard surveying of bus, cars, taxi and MRT and 1996 MMUTIS study. These were calibrated using the software EMME3 to build a traffic demand forecast model considering four scenarios: without BRT on the base year; without BRT on the design years; with BRT and with city buses traversing along EDSA; and with BRT but without the city buses traversing along EDSA on the design years 2016 and 2021. -

Chapter 5 Project Scope of Work

CHAPTER 5 PROJECT SCOPE OF WORK CHAPTER 5 PROJECT SCOPE OF WORK 5.1 MINIMUM EXPRESSWAY CONFIGURATION 5.1.1 Project Component of the Project The project is implemented under the Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Scheme in accordance with the Philippine BOT Law (R.A. 7718) and its Implementing Rules and Regulations. The project is composed of the following components; Component 1: Maintenance of Phase I facility for the period from the signing of Toll Concession Agreements (TCA) to Issuance of Toll Operation Certificate (TOC) Component 2: Design, Finance with Government Financial Support (GFS), Build and Transfer of Phase II facility and Necessary Repair/Improvement of Phase I facility. Component 3: Operation and Maintenance of Phase I and Phase II facilities. 5.1.2 Minimum Expressway Configuration of Phase II 1) Expressway Alignment Phase II starts at the end point of Phase I (Coordinate: North = 1605866.31486, East 502268.99378), runs over Sales Avenue, Andrews Avenue, Domestic Road, NAIA (MIA) Road and ends at Roxas Boulevard/Manila-Cavite Coastal Expressway (see Figure 5.1.2-1). 2) Ramp Layout Five (5) new on-ramps and five 5) new off-ramps and one (1) existing off-ramp are provided as shown in Figure 5.1.2-1. One (1) on-ramp constructed under Phase I is removed. One (1) overloaded truck/Emergency Exit is provided. One (1) on-ramp for NAIA Terminal III exit traffic and one existing off-ramp from Skyway for access to NAIA Terminal III. One (1) on-ramp along Andrews Ave. to collect traffic jam from NAIA Terminal III traffic and traffic on Andrews Ave. -

Vigía: the Network of Lookout Points in Spanish Guam

Vigía: The Network of Lookout Points in Spanish Guam Carlos Madrid Richard Flores Taitano Micronesian Area Research Center There are indications of the existence of a network of lookout points around Guam during the 18th and 19th centuries. This is suggested by passing references and few explicit allusions in Spanish colonial records such as early 19th Century military reports. In an attempt to identify the sites where those lookout points might have been located, this paper surveys some of those references and matches them with existing toponymy. It is hoped that the results will be of some help to archaeologists, historic preservation staff, or anyone interested in the history of Guam and Micronesia. While the need of using historic records is instrumental for the abovementioned purposes of this paper, focus will be given to the Chamorro place name Bijia. Historical evolution of toponymy, an area of study in need of attention, offers clues about the use or significance that a given location had in the past. The word Vigía today means “sentinel” in Spanish - the person who is responsible for surveying an area and warn of possible dangers. But its first dictionary definition is still "high tower elevated on the horizon, to register and give notice of what is discovered". Vigía also means an "eminence or height from which a significant area of land or sea can be seen".1 Holding on to the latter definition, it is noticeable that in the Hispanic world, in large coastal territories that were subjected to frequent attacks from the sea, the place name Vigía is relatively common. -

The Workshop 2016 for Protection of Cultural Heritage in Kawit, Cavite and Manila, Republic of the Philippines

The Workshop 2016 for Protection of Cultural Heritage in Kawit, Cavite and Manila, Republic of the Philippines 10-15 October 2016 &XOWXUDO+HULWDJH3URWHFWLRQ&RRSHUDWLRQ2I¿FH $VLD3DFL¿F&XOWXUDO&HQWUHIRU81(6&2 $&&8 $JHQF\IRU&XOWXUDO$IIDLUV-DSDQ The Workshop 2016 for Protection of Cultural Heritage in Kawit, Cavite and Manila, Republic of the Philippines 10-15 October 2016 Cultural Heritage Protection Cooperation Office, Asia-Pacific Cultural Centre for UNESCO (ACCU) Agency for Cultural Affairs, Japan Edited and Published by Cultural Heritage Protection Cooperation Office, Asia-Pacific Cultural Centre for UNESCO (ACCU) 757 Horen-cho, Nara 630-8113 Japan Tel: +81 (0)742 20 5001 Fax: +81 (0)742 20 5701 e-mail: [email protected] URL: http://www.nara.accu.or.jp Printed by Meishinsha Ⓒ Cultural Heritage Protection Cooperation Office, Asia-Pacific Cultural Centre for UNESCO (ACCU) 2017 Cover: Motif of the sun on the National Flag of the Philippines. It symbolises unity, freedom, people's democracy, and sovereignty. Preface The Cultural Heritage Protection Cooperation Office, Asia-Pacific Cultural Centre for UNESCO (ACCU) was established in August 1999 with the purpose of serving as a domestic centre for promoting cooperation in cultural heritage protection in the Asia- Pacific region. Subsequent to its inception, our office has been implementing a variety of programmes to help promote cultural heritage protection activities, maintaining partnerships with international organisations, such as UNESCO and the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM). The ACCU Nara’s activities include, training programmes for the human resources development, the international conference and seminar, the website for the dissemination of information relating to cultural heritage protection, and the world heritage lecture in local high schools. -

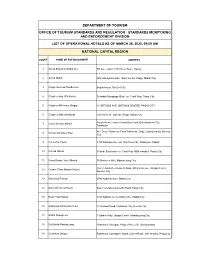

Standards Monitoring and Enforcement Division List Of

DEPARTMENT OF TOURISM OFFICE OF TOURISM STANDARDS AND REGULATION - STANDARDS MONITORING AND ENFORCEMENT DIVISION LIST OF OPERATIONAL HOTELS AS OF MARCH 26, 2020, 09:00 AM NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION COUNT NAME OF ESTABLISHMENT ADDRESS 1 Ascott Bonifacio Global City 5th ave. Corner 28th Street, BGC, Taguig 2 Ascott Makati Glorietta Ayala Center, San Lorenzo Village, Makati City 3 Cirque Serviced Residences Bagumbayan, Quezon City 4 Citadines Bay City Manila Diosdado Macapagal Blvd. cor. Coral Way, Pasay City 5 Citadines Millenium Ortigas 11 ORTIGAS AVE. ORTIGAS CENTER, PASIG CITY 6 Citadines Salcedo Makati 148 Valero St. Salcedo Village, Makati city Asean Avenue corner Roxas Boulevard, Entertainment City, 7 City of Dreams Manila Paranaque #61 Scout Tobias cor Scout Rallos sts., Brgy. Laging Handa, Quezon 8 Cocoon Boutique Hotel City 9 Connector Hostel 8459 Kalayaan Ave. cor. Don Pedro St., POblacion, Makati 10 Conrad Manila Seaside Boulevard cor. Coral Way MOA complex, Pasay City 11 Cross Roads Hostel Manila 76 Mariveles Hills, Mandaluyong City Corner Asian Development Bank, Ortigas Avenue, Ortigas Center, 12 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Quezon City 13 Discovery Primea 6749 Ayala Avenue, Makati City 14 Domestic Guest House Salem Complex Domestic Road, Pasay City 15 Dusit Thani Manila 1223 Epifanio de los Santos Ave, Makati City 16 Eastwood Richmonde Hotel 17 Orchard Road, Eastwood City, Quezon City 17 EDSA Shangri-La 1 Garden Way, Ortigas Center, Mandaluyong City 18 Go Hotels Mandaluyong Robinsons Cybergate Plaza, Pioneer St., Mandaluyong 19 Go Hotels Ortigas Robinsons Cyberspace Alpha, Garnet Road., San Antonio, Pasig City 20 Gran Prix Manila Hotel 1325 A Mabini St., Ermita, Manila 21 Herald Suites 2168 Chino Roces Ave. -

PORT of MANILA - Bls with No Entries As of February 19, 2021 Actual Cargo Arrival Date of February 15;17, 2021

PORT OF MANILA - BLs with No Entries as of February 19, 2021 Actual Cargo Arrival Date of February 15;17, 2021 ACTUAL DATE ACTUAL DATE OF No. CONSIGNEE/NOTIFY PARTY CONSIGNEE ADDRESS REGNUM BL DESCRIPTION OF ARRIVAL DISCHARGED FLOORS THE FINANCE CENTRE 26TH CORNER 9TH AVENUE BONIFACIO 1X20 CTNR 2960 CASES STC HOUSEHOLD BRUSHES 3M PHILIPPINES INC 10TH AND 1 GLOBAL 2/15/2021 2/15/2021 WHL0015-21 SZX210069120 501 SCOTCH BRITE TM FLOOR SCRUB 6 CS AND 11TH CITY TAGUIG METRO MANILA 1634 ETC HS CODE 9603909090 PHILIPPINES 1 X 40 H DC CONTAINER4 PACKAGESSTEEL MANUFACTURING PHILS INC. 3134 FASTENERSSTEEL FRAME ARMSERVO 2 ACCURA MACHINERY AND V.MAPA ST.,STA. MESA, MANILA 1016 2/15/2021 2/15/2021 HMM0006-21 HDMUSHAZ03834900 MOTORHYDROCYLINDER TEL 0086 512 PHILIPPINES REL 44 2085 397 322 81619888,FAX 0086 512 81604299 TEL 0063 2 7161355FAX 0063 2 7161275MR.EDU ADDRESS RM 308 CALVO BLDG 266 STEEL COILS HS CODE 7212 50 ZINC WIRE HS CODE AGANDA GENERAL ESCOLTA STREET BRGY 291 ZONE 3 2/15/2021 2/15/2021 APL0014-21 AHYD010495 7904 00 TEXTILE FLOOR COVERINGS HS CODE 5703 MERCHANDISE 027 BINONDO MANILA 1006 90 FREIGHT PREPAID 20GPX6 PHILIPPINES 117 P PARADA ST STA LUCIA SAN STOVES AND SPARE PARTS HS CODE 7321 12 TEL AIKON TEDSIM MARKETING CO 4 JUAN METRO MANILA FAX NO 528 2/15/2021 2/15/2021 APL0014-21 CNH0272829 86 731 55188820 FAX 86 731 55188822 FREIGHT INC 0335 PREPAID ADDRESS 77 KANLAON HIGHWAY MEDICAL EQUIPMENT HIGH FLOW NASAL CANNULA ALJERON MEDICAL HILLS MANDALUYONG 1550 OXYGEN THERAPY DEVICE HS CODE 901920 5 2/15/2021 2/15/2021 APL0014-21 CMZ0521801 ENTERPRISES PHILIPPINES TIN 171 085 245 000 TEL FREIHGT PREPAID EMAIL F TONOG 63 917 813 9552 ALJERONMEDICAL COM STC 279 CARTONS SPHYGMOMANOMETER LOYOLA BLDG HILADO MALASPINA STETHOSCOPE THREE WAY STOPCOCK IV 6 ALL PRO CORPORATION ST VILLAMONTE BACOLOD CITY 6100 2/15/2021 2/15/2021 HMM0006-21 S00102852 CATHETER STRIP CLIP CAP BLOOD LANCET BLOOD PHILIPPINES COLLECTION TUBE NEBULIZER INFANT PHOTO ADD UNIT 122 GRAND ALWAYS LUCKY STAR 101 EMERALDTOWER 6 F. -

Researchonline@JCU

ResearchOnline@JCU This is the Published Version of a paper published in the journal Pacific Journalism Review: Forbes, Amy (2015) Courageous women in media: Marcos and censorship in the Philippines. Pacific Journalism Review, 21 (1). pp. 195-210. http://www.pjreview.info/articles/courageous-women- media-marcos-and-censorship-philippines-1026 POLITICAL JOURNALISM IN THE ASIA-PACIFIC PHILIPPINES 14. Courageous women in media Marcos and censorship in the Philippines Abstract: When Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos declared Martial Law in 1972, press freedom became the first casualty in the country that once boasted of being the ‘freest in Asia’. Printing presses, newspaper offices, television and radio stations were raided and padlocked. Marcos was especially fearful of the press and ordered the arrest of journalists whom he charged with conspiring with the ‘Left’. Pressured into lifting martial law after nearly 10 years, Marcos continued to censor the media, often de- manding publishers to sack journalists whose writing he disapproved of. Ironically, he used the same ‘subversive writings’ as proof to Western observers that freedom of the press was alive and well under his dictatorship. This article looks at the writings of three female journalists from the Bulletin Today. The author examines the work of Arlene Babst, Ninez Cacho-Olivares, and Melinda de Jesus and how they traversed the dictator’s fickle, sometimes volatile, reception of their writing. Interviewed is Ninez Cacho-Olivare, who used humour and fairy tales in her popular column to criticise Marcos, his wife, Imelda, and even the military that would occasionally ‘invite’ her for questioning. She explains an unwritten code of conduct between Marcos and female journalists that served to shield them from total political repression. -

G. Bankoff Selective Memory and Collective Forgetting

G. Bankoff Selective memory and collective forgetting. Historiography and the Philippine centennial of 1898 In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, The PhilippinesHistorical and social studies 157 (2001), no: 3, Leiden, 539-560 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/28/2021 07:08:04PM via free access GREG BANKOFF Selective Memory and Collective Forgetting Historiography and the Philippine Centennial of 1898 The fanfare and extravaganza with which the centennial of the Revolution of 1896-1898 was celebrated in the Philippines serves largely to obscure the sur- prising lack of unanimity concerning the significance of the occasion or even the purpose of the festivities. Philippine history, more especially the historio- graphy of its colonial period, poses some particular problems in serving as the basis from which to fashion an identity suitable to the modern citizens of a nation-state. These problems are not restricted to the Philippines, but the combination of features is certainly specific to the history of that nation and differentiates its historiography from that of others in the region. Attention has long been drawn to the unique geographical location and cultural experi- ence of the islands; indeed D.G.E. Hall even omitted the Philippines from the first edition of his seminal history of Southeast Asia (Hall 1955). But these observations on their own offer no insuperable obstacle to the creation of a national historiography. Far more significant is the lack of appropriate his- torical experiences whose symbolic value make of them suitable rallying points round which a counter-hegemonic and anti-colonial historiography can coalesce and flourish.1 The history of nations is always presented in the form of a narrative, the fulfilment of a project that stretches back over the centuries along which are moments of coming to self-awareness that prove to be decisive in the self- manifestation of national personality (Balibar 1991:86; Bhabha 1990:1).