Use of the European Severe Weather Database to Verify Satellite-Based Storm Detection Or Nowcasting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Optimized Autonomous Space In-Situ Sensor-Web for Volcano Monitoring

Optimized Autonomous Space In-situ Sensor-Web for Volcano Monitoring Wen-Zhan Song Behrooz Shirazi Renjie Huang Mingsen Xu Nina Peterson fsongwz, shirazi, renjie huang, mingsen xu, [email protected] Sensorweb Research Laboratory, Washington State University Rick LaHusen John Pallister Dan Dzurisin Seth Moran Mike Lisowski frlahusen, jpallist, dzurisin, smoran, [email protected] Cascades Volcano Observatory, U.S. Geological Survey Sharon Kedar Steve Chien Frank Webb Aaron Kiely Joshua Doubleday Ashley Davies David Pieri fsharon.kedar, steve.chien, frank.webb, aaron.b.kiely, jdoubled, ashley.davies, [email protected] Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology Abstract—In response to NASA’s announced requirement for situ Sensor-web (OASIS) has two-way communication ca- Earth hazard monitoring sensor-web technology, a multidis- pability between ground and space assets, use both space ciplinary team involving sensor-network experts (Washington and ground data for optimal allocation of limited bandwidth State University), space scientists (JPL), and Earth scientists (USGS Cascade Volcano Observatory (CVO)), have developed a resources on the ground, and uses smart management of prototype of dynamic and scalable hazard monitoring sensor-web competing demands for limited space assets [1]. and applied it to volcano monitoring. The combined Optimized This research responds to the NASA objective [2] to Autonomous Space - In-situ Sensor-web (OASIS) has two-way “conduct a program of research and technology development communication capability between ground and space assets, to advance Earth observation from space, improve scientific uses both space and ground data for optimal allocation of limited bandwidth resources on the ground, and uses smart understanding, and demonstrate new technologies with the management of competing demands for limited space assets. -

Using Earth Observation Data to Improve Health in the United States Accomplishments and Future Challenges

a report of the csis technology and public policy program Using Earth Observation Data to Improve Health in the United States accomplishments and future challenges 1800 K Street, NW | Washington, DC 20006 Tel: (202) 887-0200 | Fax: (202) 775-3199 Author E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.csis.org Lyn D. Wigbels September 2011 ISBN 978-0-89206-668-1 Ë|xHSKITCy066681zv*:+:!:+:! a report of the csis technology and public policy program Using Earth Observation Data to Improve Health in the United States accomplishments and future challenges Author Lyn D. Wigbels September 2011 About CSIS At a time of new global opportunities and challenges, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) provides strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to decisionmakers in government, international institutions, the private sector, and civil society. A bipartisan, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., CSIS conducts research and analysis and devel- ops policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Founded by David M. Abshire and Admiral Arleigh Burke at the height of the Cold War, CSIS was dedicated to finding ways for America to sustain its prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. Since 1962, CSIS has grown to become one of the world’s preeminent international policy institutions, with more than 220 full-time staff and a large network of affiliated scholars focused on defense and security, regional stability, and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global development and economic integration. Former U.S. senator Sam Nunn became chairman of the CSIS Board of Trustees in 1999, and John J. -

Soaring Weather

Chapter 16 SOARING WEATHER While horse racing may be the "Sport of Kings," of the craft depends on the weather and the skill soaring may be considered the "King of Sports." of the pilot. Forward thrust comes from gliding Soaring bears the relationship to flying that sailing downward relative to the air the same as thrust bears to power boating. Soaring has made notable is developed in a power-off glide by a conven contributions to meteorology. For example, soar tional aircraft. Therefore, to gain or maintain ing pilots have probed thunderstorms and moun altitude, the soaring pilot must rely on upward tain waves with findings that have made flying motion of the air. safer for all pilots. However, soaring is primarily To a sailplane pilot, "lift" means the rate of recreational. climb he can achieve in an up-current, while "sink" A sailplane must have auxiliary power to be denotes his rate of descent in a downdraft or in come airborne such as a winch, a ground tow, or neutral air. "Zero sink" means that upward cur a tow by a powered aircraft. Once the sailcraft is rents are just strong enough to enable him to hold airborne and the tow cable released, performance altitude but not to climb. Sailplanes are highly 171 r efficient machines; a sink rate of a mere 2 feet per second. There is no point in trying to soar until second provides an airspeed of about 40 knots, and weather conditions favor vertical speeds greater a sink rate of 6 feet per second gives an airspeed than the minimum sink rate of the aircraft. -

More Observations of Small Funnel Clouds and Other Tubular Clouds

3714 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW VOLUME 133 PICTURE OF THE MONTH More Observations of Small Funnel Clouds and Other Tubular Clouds HOWARD B. BLUESTEIN School of Meteorology, University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma (Manuscript received 14 March 2005, in final form 20 May 2005) ABSTRACT In this brief contribution, photographic documentation is provided of a variety of small, tubular-shaped clouds and of a small funnel cloud pendant from a convective cloud that appears to have been modified by flow over high-altitude mountains in northeast Colorado. These funnel clouds are contrasted with others that have been documented, including those pendant from high-based cumulus clouds in the plains of the United States. It is suggested that the mountain funnel cloud is unique in that flow over high terrain is probably responsible for its existence; other types of small funnel clouds are seen both over elevated, mountainous terrain and over flat terrain at lower elevations. 1. Introduction which the benign funnel clouds occur so that if they are observed, severe weather warnings are not issued. Fur- Bluestein (1994) and others (e.g., Doswell 1985, p. thermore, the small funnel clouds are of interest in their 107; McCaul and Blanchard 1990) have documented, in own right because their dynamics are not well under- the plains of the United States, small funnel clouds pen- stood, and they have not been discussed in the litera- dant from convective clouds whose updrafts appear to ture to the much greater extent that the dynamics of be rooted above the boundary layer. Above many of tornadoes have (e.g., Davies-Jones 1986). -

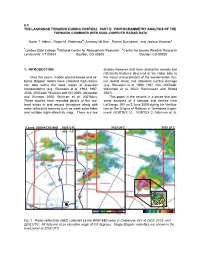

The Lagrange Torando During Vortex2. Part Ii: Photogrammetry Analysis of the Tornado Combined with Dual-Doppler Radar Data

6.3 THE LAGRANGE TORANDO DURING VORTEX2. PART II: PHOTOGRAMMETRY ANALYSIS OF THE TORNADO COMBINED WITH DUAL-DOPPLER RADAR DATA Nolan T. Atkins*, Roger M. Wakimoto#, Anthony McGee*, Rachel Ducharme*, and Joshua Wurman+ *Lyndon State College #National Center for Atmospheric Research +Center for Severe Weather Research Lyndonville, VT 05851 Boulder, CO 80305 Boulder, CO 80305 1. INTRODUCTION studies, however, that have related the velocity and reflectivity features observed in the radar data to Over the years, mobile ground-based and air- the visual characteristics of the condensation fun- borne Doppler radars have collected high-resolu- nel, debris cloud, and attendant surface damage tion data within the hook region of supercell (e.g., Bluestein et al. 1993, 1197, 204, 2007a&b; thunderstorms (e.g., Bluestein et al. 1993, 1997, Wakimoto et al. 2003; Rasmussen and Straka 2004, 2007a&b; Wurman and Gill 2000; Alexander 2007). and Wurman 2005; Wurman et al. 2007b&c). This paper is the second in a series that pre- These studies have revealed details of the low- sents analyses of a tornado that formed near level winds in and around tornadoes along with LaGrange, WY on 5 June 2009 during the Verifica- radar reflectivity features such as weak echo holes tion on the Origins of Rotation in Tornadoes Exper- and multiple high-reflectivity rings. There are few iment (VORTEX 2). VORTEX 2 (Wurman et al. 5 June, 2009 KCYS 88D 2002 UTC 2102 UTC 2202 UTC dBZ - 0.5° 100 Chugwater 100 50 75 Chugwater 75 330° 25 Goshen Co. 25 km 300° 50 Goshen Co. 25 60° KCYS 30° 30° 50 80 270° 10 25 40 55 dBZ 70 -45 -30 -15 0 15 30 45 ms-1 Fig. -

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists. -

The Spatial Distribution of Ocean Waves in Tropical Cyclones

AUGUST 2020 T A M I Z I A N D Y O U N G 2123 The Spatial Distribution of Ocean Waves in Tropical Cyclones ALI TAMIZI AND IAN R. YOUNG Department of Infrastructure Engineering, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia (Manuscript received 27 January 2020, in final form 28 May 2020) ABSTRACT The spatial structure of both the wind and wave fields within tropical cyclones is investigated using two large databases. The first of these was compiled from global overpasses of tropical cyclones by satellite altimeters. The second dataset consists of an extensive collection of North American buoy measurements during the passage of tropical cyclones (hurricanes). The combined datasets confirm the vortex structure of the tropical cyclone wind field with the strongest winds to the right (Northern Hemisphere) of the storm. The wave field largely mirrors the wind field but with greater right–left asymmetry that results from the extended fetch to the right of the translating tropical cyclone. The extensive in situ buoy database confirms previous studies indi- cating that the one-dimensional spectra are generally unimodal. The directional spectra are, however, di- rectionally skewed, consisting of remotely generated waves radiating out from the center of the storm and locally generated wind sea. The one-dimensional wave spectra have many similarities to fetch-limited cases, although for a given peak frequency the spectra contain less energy than for a fetch-limited case. This result is consistent with the fact that much of the wave field is dominated by remotely generated waves. 1. Introduction This paper attempts to build an extensive database of observations of tropical cyclone wave conditions In tropical and subtropical regions, tropical cyclones from a number of sources. -

Assessment of Phytoremediation As an In-Situ Technique for Cleaning Oil-Contaminated Sites

Assessment of Phytoremediation as an In-Situ Technique for Cleaning Oil-Contaminated Sites Prepared by: C.M. Frick, R.E. Farrell and J.J. Germida Department of Soil Science University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, SK Canada S7N 5A8 Submitted to: Petroleum Technology Alliance of Canada (PTAC) Calgary, AB [email protected] [email protected] December 29, 1999 Support for this project was provided through an initiative sponsored by the Petroleum Technology Alliance Canada (PTAC). Funding was provided by Environment Canada, Quest/Amoco, the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP), and the Saskatchewan Agriculture & Food strategic research program in Soil Biology & Conservation. This document was developed as a literature review and technology assessment of phytoremediation and its alternatives. As such, the stakeholders do not endorse the use of any specific technology, nor do they assume any liabilities with respect to the use of, or damages resulting from the use of, any information, apparatus, method, or process discussed in this document. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation of use. Requests for reprints of this report should be addressed to: PTAC Dr. R.E. Farrell Petroleum Technology Alliance Canada University of Saskatchewan 17th Floor, One Palliser Square Department of Soil Science 125 9th Avenue S.E. 51 Campus Drive Calgary, Alberta T2G 0P8 Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A8 Canada Canada Cover photographs courtesy of Trevor Carlson (Federated Co-Operatives, Ltd., Saskatoon, SK). ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Phytoremediation, the use of plants and their associated microorganisms for the in situ treatment of contaminated soils, is a steadily emerging technology with potential for the effective and inexpensive cleanup of a broad range of organic and inorganic wastes. -

The State of in Situ Management the STATE of in SITU MANAGEMENT

CHAPTER 2 Chapter 2 The state of in situ management THE STATE OF IN SITU MANAGEMENT 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Conservation and management of PGRFA in The CBD defines in situ conservation as “the wild ecosystems conservation of ecosystems and natural habitats and the maintenance and recovery of viable populations Many plant species growing in wild ecosystems are of species in their natural surroundings and, in valuable for food and agriculture and may play an the case of domesticated or cultivated species, in important cultural role in local societies. They can the surroundings where they have developed their provide a safety net when food is scarce and are distinctive properties.” While the concept has evolved increasingly marketed locally and internationally, since the CBD was adopted, this definition is used providing an important contribution to household in several major international treaties and initiatives incomes. Approximately a third of the country reports including the ITPGRFA and the Global Strategy for received mentioned the use of wild-harvested plants. Plant Conservation (GSPC). In situ conservation is Nigeria, for example, cited the use of African mango often envisaged as taking place in protected areas or (Irvingia gabonensis) and locust bean (Parkia biglobosa) habitats (as opposed to ex situ conservation) and can in times of food shortage. either be targeted at species or the ecosystem in which Grassland and forage species are another important they occur. It is a particularly important method of component of agrobiodiversity, especially in countries conservation for species that are difficult to conserve where livestock production is a major contributor to ex situ, such as many CWR. -

Extreme Weather Events in Europe: Preparing for Climate Change Adaptation

Extreme Weather Events in Europe: preparing for climate change adaptation October 2013 ISBN (print) 978-82-7144-100-5 ISBN (electronic) 978-82-7144-101-2 In cooperation with This report can be found at www.dnva.no Produced by the Norwegian Meteorological Institute Extreme Weather Events in Europe: preparing for climate change adaptation Øystein Hov, Ulrich Cubasch, Erich Fischer, Peter Höppe, Trond Iversen, Nils Gunnar Kvamstø, Zbigniew W. Kundzewicz, Daniela Rezacova, David Rios, Filipe Duarte Santos, Bruno Schädler, Ottó Veisz, Christos Zerefos, Rasmus Benestad, John Murlis, M. Donat, Gregor C. Leckebusch, Uwe Ulbrich. Extreme Weather Events in Europe: preparing for climate change adaptation In cooperation with CONTRIBUTORS Professor Øystein Hov, Norwegian Meteorological Institute, Norway† Professor Ulrich Cubasch, Free University of Berlin, Germany* Dr Erich Fischer, Institute for Atmospheric and Climatic Science, ETH Zurich, Switzerland* Professor Peter Höppe, Geo Risks Research/Corporate Climate Centre, Munich Re, Germany* Professor Trond Iversen, Norwegian Meteorological Institute, Norway* Professor Nils Gunnar Kvamstø, Department of Geophysics, University of Bergen, Norway* Professor Zbigniew W. Kundzewicz, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland* Professor Daniela Rezacova, Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Prague, Czech Republic* Professor David Rios, Royal Academy of Sciences, Spain* Professor Filipe Duarte Santos, Lisbon University, Portugal* Dr Bruno Schädler, University of Berne, Switzerland* Professor Ottó Veisz, Agricultural Research Institute of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest, Hungary* Professor Christos Zerefos, University of Athens, Greece* Dr Rasmus Benestad (Working Group Researcher), Norwegian Meteorological Institute, Oslo, Norway Professor John Murlis, EASAC Environment Programme Secretary Dr M. Donat, Institut für Meteorologie, Freie Universität Berlin, Germany; now at Climate Change Research Centre, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia Dr Gregor C. -

Glossary of Severe Weather Terms

Glossary of Severe Weather Terms -A- Anvil The flat, spreading top of a cloud, often shaped like an anvil. Thunderstorm anvils may spread hundreds of miles downwind from the thunderstorm itself, and sometimes may spread upwind. Anvil Dome A large overshooting top or penetrating top. -B- Back-building Thunderstorm A thunderstorm in which new development takes place on the upwind side (usually the west or southwest side), such that the storm seems to remain stationary or propagate in a backward direction. Back-sheared Anvil [Slang], a thunderstorm anvil which spreads upwind, against the flow aloft. A back-sheared anvil often implies a very strong updraft and a high severe weather potential. Beaver ('s) Tail [Slang], a particular type of inflow band with a relatively broad, flat appearance suggestive of a beaver's tail. It is attached to a supercell's general updraft and is oriented roughly parallel to the pseudo-warm front, i.e., usually east to west or southeast to northwest. As with any inflow band, cloud elements move toward the updraft, i.e., toward the west or northwest. Its size and shape change as the strength of the inflow changes. Spotters should note the distinction between a beaver tail and a tail cloud. A "true" tail cloud typically is attached to the wall cloud and has a cloud base at about the same level as the wall cloud itself. A beaver tail, on the other hand, is not attached to the wall cloud and has a cloud base at about the same height as the updraft base (which by definition is higher than the wall cloud). -

Title Author(S)

th 5 European Conference on Severe Storms 12 - 16 October 2009 - Landshut - GERMANY ECSS 2009 Abstracts by session ECSS 2009 - 5th European Conference on Severe Storms 12-16 October 2009 - Landshut – GERMANY List of the abstract accepted for presentation at the conference: O – Oral presentation P – Poster presentation Session 09: Severe storm case studies and field campaigns, e.g. COPS, THORPEX, VORTEX2 Page Type Abstract Title Author(s) An F3 downburst in Austria - a case study with special G. Pistotnik, A. M. Holzer, R. 265 O focus on the importance of real-time site surveys Kaltenböck, S. Tschannett J. Bech, N. Pineda, M. Aran, J. An observational analysis of a tornadic severe weather 267 O Amaro, M. Gayà, J. Arús, J. event Montanyà, O. van der Velde Case study: Extensive wind damage across Slovenia on July M. Korosec, J. Cedilnik 269 O 13th, 2008 Observed transition from an elevated mesoscale convective J. Marsham, S. Trier, T. 271 O system to a surface based squall line: 13th June, Weckwerth, J. Wilson, A. Blyth IHOP_2002 08/08/08: classification and simulation challenge of the A. Pucillo, A. Manzato 273 O FVG olympic storm H. Bluestein, D. Burgess, D. VORTEX2: The Second Verification of the Origins of Dowell, P. Markowski, E. 275 O Rotation in Tornadoes Experiment Rasmussen, Y. Richardson, L. Wicker, J. Wurman Observations of the initiation and development of severe A. Blyth, K. Browning, J. O convective storms during CSIP Marsham, P. Clark, L. Bennett The development of tornadic storms near a surface warm P. Groenemeijer, U. Corsmeier, 277 O front in central England during the Convective Storm C.