The Morphosyntax of Case and Adpositions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animacy and Alienability: a Reconsideration of English

Running head: ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 1 Animacy and Alienability A Reconsideration of English Possession Jaimee Jones A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2016 ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Jaeshil Kim, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Paul Müller, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Jeffrey Ritchey, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 3 Abstract Current scholarship on English possessive constructions, the s-genitive and the of- construction, largely ignores the possessive relationships inherent in certain English compound nouns. Scholars agree that, in general, an animate possessor predicts the s- genitive while an inanimate possessor predicts the of-construction. However, the current literature rarely discusses noun compounds, such as the table leg, which also express possessive relationships. However, pragmatically and syntactically, a compound cannot be considered as a true possessive construction. Thus, this paper will examine why some compounds still display possessive semantics epiphenomenally. The noun compounds that imply possession seem to exhibit relationships prototypical of inalienable possession such as body part, part whole, and spatial relationships. Additionally, the juxtaposition of the possessor and possessum in the compound construction is reminiscent of inalienable possession in other languages. Therefore, this paper proposes that inalienability, a phenomenon not thought to be relevant in English, actually imbues noun compounds whose components exhibit an inalienable relationship with possessive semantics. -

The Strategy of Case-Marking

Case marking strategies Helen de Hoop & Andrej Malchukov1 Radboud University Nijmegen DRAFT January 2006 Abstract Two strategies of case marking in natural languages are discussed. These are defined as two violable constraints whose effects are shown to converge in the case of differential object marking but diverge in the case of differential subject marking. The strength of the case bearing arguments will be shown to be of utmost importance for case marking as well as voice alternations. The strength of arguments can be viewed as a function of their discourse prominence. The analysis of the case marking patterns we find cross-linguistically is couched in a bidirectional OT analysis. 1. Assumptions In this section we wish to put forward our three basic assumptions: (1) In ergative-absolutive systems ergative case is assigned to the first argument x of a two-place relation R(x,y). (2) In nominative-accusative systems accusative case is assigned to the second argument y of a two-place relation R(x,y). (3) Morphologically unmarked case can be the absence of case. The first two assumptions deal with the linking between the first (highest) and second (lowest) argument in a transitive sentence and the type of case marking. For reasons of convenience, we will refer to these arguments quite sloppily as the subject and the object respectively, although we are aware of the fact that the labels subject and object may not be appropriate in all contexts, dependent on how they are actually defined. In many languages, ergative and accusative case are assigned only or mainly in transitive sentences, while in intransitive sentences ergative and accusative case are usually not assigned. -

Sinitic Languages of Northwest China: Where Did Their Case Marking Come From?* Dan Xu

Sinitic languages of Northwest China: Where did their case marking come from?* Dan Xu To cite this version: Dan Xu. Sinitic languages of Northwest China: Where did their case marking come from?*. Cao, Djamouri and Peyraube. Languages in contact in Northwestern China, 2015. hal-01386250 HAL Id: hal-01386250 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01386250 Submitted on 31 Oct 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Copyright Sinitic languages of Northwest China: Where did their case marking come from?* XU DAN 1. Introduction In the early 1950s, Weinreich (1953) published a monograph on language contact. Although this subject drew the attention of a few scholars, at the time it remained marginal. Over two decades, several scholars including Moravcsik (1978), Thomason and Kaufman (1988), Aikhenvald (2002), Johanson (2002), Heine and Kuteva (2005) and others began to pay more attention to language contact. As Thomason and Kaufman (1988: 23) pointed out, language is a system, or even a system of systems. Perhaps this is why previous studies (Sapir, 1921: 203; Meillet 1921: 87) indicated that grammatical categories are not easily borrowed, since grammar is a system. -

Nouns, Verbs and Sentences 98-348: Lecture 2 Any Questions About the Homework? Everyone Read One Word

Nouns, Verbs, and Sentences 98-348: Lecture 2 Nouns, verbs and sentences 98-348: Lecture 2 Any questions about the homework? Everyone read one word • Þat var snimma í ǫndverða bygð goðanna, þá er goðin hǫfðu sett Miðgarð ok gǫrt Valhǫ́ll, þá kom þar smiðr nǫkkurr ok bauð at gøra þeim borg á þrim misserum svá góða at trú ok ørugg væri fyrir bergrisum ok hrímþursum, þótt þeir kœmi inn um Miðgarð; en hann mælti sér þat til kaups, at hann skyldi eignask Freyju, ok hafa vildi hann sól ok mána. How do we build sentences with words? • English • The king slays the serpent. • The serpent slays the king. • OI • Konungr vegr orm. king slays serpent (What does this mean?) • Orm vegr konugr. serpent slays king (What does this mean?) How do we build sentences with words? • English • The king slays the serpent. • The serpent slays the king. They have the • OI same meaning! • Konungr vegr orm. But why? king slays serpent ‘The king slays the serpent.’ • Orm vegr konugr. serpent slays king ‘The king slays the serpent.’ Different strategies to mark subjects/objects • English uses word order: (whatever noun) slays (whatever noun) This noun is a subject! This noun is a subject! • OI uses inflection: konung r konung This noun is a subject! This noun is an object! Inflection • Words change their forms to encode information. • This happens in a lot of languages! • English: • the kid one kid • the kids more than one kid • We say that English nouns inflect for number, i.e. English nouns change forms based on what number they have. -

The Case of Restricted Locatives Ora Matushansky

The case of restricted locatives Ora Matushansky To cite this version: Ora Matushansky. The case of restricted locatives. Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung , 2019, 23 (2), 10.18148/sub/2019.v23i2.604. halshs-02431372 HAL Id: halshs-02431372 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02431372 Submitted on 7 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The case of restricted locatives1 Ora MATUSHANSKY — SFL (CNRS/Université Paris-8)/UiL OTS/Utrecht University Abstract. This paper examines the cross-linguistic phenomenon of locative case restricted to a closed class of items (L-nouns). Starting with Latin, I suggest that the restriction is semantic in nature: L-nouns denote in the spatial domain and hence can be used as locatives without further material. I show how the independently motivated hypothesis that directional PPs consist of two layers, Path and Place, explains the directional uses of L-nouns and the cases that are assigned then, and locate the source of the locative case itself in p0, for which I then provide a clear semantic contribution: a type-shift from the domain of loci to the object domain. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

A Crosslinguistic Approach to Double Nominative and Biabsolutive Constructions

A Crosslinguistic Approach to Double Nominative and Biabsolutive Constructions: Evidence from Korean and Daghestanian∗ Andrei Antonenko1 and Jisung Sun2 Stony Brook University1,2 1. Introduction Distribution of case among distinct grammatical relations is one of the most frequently studied topics in the syntactic theory. Canonical cases are, in accusative languages, subjects of both intransitive and transitive verbs being nominative, while direct objects of transitive verbs are usually marked accusative. In ergative languages, subjects of intransitive verbs share properties with direct objects of transitive verbs, and are marked absolutive. Subjects of transitive verbs are usually ergative. When you look into world languages, however, there are ‘non-canonical’ case patterns too. Probably the most extreme kind of non-canonical case system would be so-called Quirky Subject constructions in Icelandic (see Sigurðsson 2002). This paper concerns constructions, in which two nominals are identically case-marked in a clause, as observed in Korean and Daghestanian languages. Daghestanian languages belong to Nakh-Daghestanian branch of North Caucasian family. Nakh-Daghestanian languages are informally divided into Nakh languages, such as Chechen and Ingush, spoken in Chechnya and the Republic of Ingushetia, respectively; and Daghestanian languages, spoken in the Republic of Daghestan. Those regions are located in the Caucasian part of Russian Federation. Some Daghestanian languages are also spoken in Azerbaijan and Georgia. This study focuses on Daghestanian languages, such as Archi, Avar, Dargwa, Hinuq, Khwarshi, Lak and Tsez, due to similar behaviors of them with respect to the described phenomenon. 2. Ergativity in Daghestanian Aldridge (2004) proposes that there are two types of syntactically ergative languages, based on which argument is performing functions typical for subjects. -

Understanding English Non-Count Nouns and Indefinite Articles

Understanding English non-count nouns and indefinite articles Takehiro Tsuchida Digital Hollywood University December 20, 2010 Introduction English nouns are said to be categorised into several groups according to certain criteria. Among such classifications is the division of count nouns and non-count nouns. While count nouns have such features as plural forms and ability to take the indefinite article a/an, non-count nouns are generally considered to be simply the opposite. The actual usage of nouns is, however, not so straightforward. Nouns which are usually regarded as uncountable sometimes take the indefinite article and it seems fairly difficult for even native speakers of English to expound the mechanism working in such cases. In particular, it seems to be fairly peculiar that the noun phrase (NP) whose head is the abstract „non-count‟ noun knowledge often takes the indefinite article a/an and makes such phrase as a good knowledge of Greek. The aim of this paper is to find out reasonable answers to the question of why these phrases occur in English grammar and thereby to help native speakers/teachers of English and non-native teachers alike to better instruct their students in 1 the complexity and profundity of English count/non-count dichotomy and actual usage of indefinite articles. This report will first examine the essential qualities of non-count nouns and indefinite articles by reviewing linguistic literature. Then, I shall conduct some research using the British National Corpus (BNC), focusing on statistical and semantic analyses, before finally certain conclusions based on both theoretical and actual observations are drawn. -

The Ongoing Eclipse of Possessive Suffixes in North Saami

Te ongoing eclipse of possessive sufxes in North Saami A case study in reduction of morphological complexity Laura A. Janda & Lene Antonsen UiT Te Arctic University of Norway North Saami is replacing the use of possessive sufxes on nouns with a morphologically simpler analytic construction. Our data (>2K examples culled from >.5M words) track this change through three generations, covering parameters of semantics, syntax and geography. Intense contact pressure on this minority language probably promotes morphological simplifcation, yielding an advantage for the innovative construction. Te innovative construction is additionally advantaged because it has a wider syntactic and semantic range and is indispensable, whereas its competitor can always be replaced. Te one environment where the possessive sufx is most strongly retained even in the youngest generation is in the Nominative singular case, and here we fnd evidence that the possessive sufx is being reinterpreted as a Vocative case marker. Keywords: North Saami; possessive sufx; morphological simplifcation; vocative; language contact; minority language 1. Te linguistic landscape of North Saami1 North Saami is a Uralic language spoken by approximately 20,000 people spread across a large area in northern parts of Norway, Sweden and Finland. North Saami is in a unique situation as the only minority language in Europe under intense pressure from majority languages from two diferent language families, namely Finnish (Uralic) in the east and Norwegian and Swedish (Indo-European 1. Tis research was supported in part by grant 22506 from the Norwegian Research Council. Te authors would also like to thank their employer, UiT Te Arctic University of Norway, for support of their research. -

Count Vs Noncount Nouns

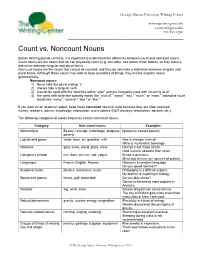

George Mason University Writing Center writingcenter.gmu.edu The [email protected] Writing Center 703.993.1200 Count vs. Noncount Nouns Before forming plurals correctly, it is important to understand the difference between count and noncount nouns. Count nouns are the nouns that we can physically count (e.g. one table, two tables, three tables), so they make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Noncount nouns are the nouns that cannot be counted, and they do not make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Although these nouns may refer to large quantities of things, they act like singular nouns grammatically. Noncount nouns: 1) Never take the plural ending “s” 2) Always take a singular verb 3) Cannot be used with the indefinite article “a/an” and are frequently used with no article at all 4) Are used with collective quantity words like “a lot of,” “some,” “any,” “much,” or “more,” instead of count words like “many,” “several,” “two,” or “few.” If you work on an academic paper, keep these noncount nouns in mind because they are often misused: money, research, advice, knowledge, information, and evidence (NOT moneys, researches, advices, etc.). The following categories of words frequently contain noncount nouns: Category Non-count nouns Examples Abstractions Beauty, revenge, knowledge, progress, Ignorance causes poverty. poverty Liquids and gases water, beer, air, gasoline, milk Gas is cheaper than oil. Wine is my favorite beverage. Materials gold, silver, wood, glass, sand He had a will made of iron. Gold is more valuable than silver. Categories of food rice, flour, cheese, salt, yogurt Bread is delicious. -

Genitive Constructions in Coptic Barbara Egedi

Genitive constructions in Coptic Barbara Egedi 1. Introduction 1.1. Definition of ‘Coptic’ Coptic is the language of Christian Egypt (4th to 14th century) written in a specific version of the Greek alphabet. It was gradually superseded by Ara- bic from the ninth century onward, but it survived to the present time as the liturgical language of the Christian church of Egypt. In this paper I examine only one of its main dialects, the Sahidic Coptic and I use a transcription which simply reflects the Coptic letters irrespectively of phonological de- tails.1 1.2. UG in the reconstruction of dead languages Natural languages are claimed to have universal properties or principles which constitute what is referred to as Universal Grammar. Accepting cer- tain universal principles and observing the corresponding parameters in Coptic, we can also analyse a language without living native speakers, and explain its structural relations with the help of coherent models. For example, it is considered a universal principle that the projections of lexical heads are extended by one or more functional projections. If we assume that it can be demonstrated in many languages, why could not we suppose the same in the case of Coptic? Indeed, as it will be shown in chap- ter 4, there are at least two functional projections above Coptic lexical noun phrase as well. The aim of this paper is to provide an adequate account of the basic structure of the Coptic NP within the theoretical framework of the Mini- malist Program (a short summary of which will be found in the following section); at the same time, I intend to find the answer to unsolved questions related to genitive constructions. -

Prior Linguistic Knowledge Matters : the Use of the Partitive Case In

B 111 OULU 2013 B 111 UNIVERSITY OF OULU P.O.B. 7500 FI-90014 UNIVERSITY OF OULU FINLAND ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS ACTA SERIES EDITORS HUMANIORAB Marianne Spoelman ASCIENTIAE RERUM NATURALIUM Marianne Spoelman Senior Assistant Jorma Arhippainen PRIOR LINGUISTIC BHUMANIORA KNOWLEDGE MATTERS University Lecturer Santeri Palviainen CTECHNICA THE USE OF THE PARTITIVE CASE IN FINNISH Docent Hannu Heusala LEARNER LANGUAGE DMEDICA Professor Olli Vuolteenaho ESCIENTIAE RERUM SOCIALIUM University Lecturer Hannu Heikkinen FSCRIPTA ACADEMICA Director Sinikka Eskelinen GOECONOMICA Professor Jari Juga EDITOR IN CHIEF Professor Olli Vuolteenaho PUBLICATIONS EDITOR Publications Editor Kirsti Nurkkala UNIVERSITY OF OULU GRADUATE SCHOOL; UNIVERSITY OF OULU, FACULTY OF HUMANITIES, FINNISH LANGUAGE ISBN 978-952-62-0113-9 (Paperback) ISBN 978-952-62-0114-6 (PDF) ISSN 0355-3205 (Print) ISSN 1796-2218 (Online) ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS B Humaniora 111 MARIANNE SPOELMAN PRIOR LINGUISTIC KNOWLEDGE MATTERS The use of the partitive case in Finnish learner language Academic dissertation to be presented with the assent of the Doctoral Training Committee of Human Sciences of the University of Oulu for public defence in Keckmaninsali (Auditorium HU106), Linnanmaa, on 24 May 2013, at 12 noon UNIVERSITY OF OULU, OULU 2013 Copyright © 2013 Acta Univ. Oul. B 111, 2013 Supervised by Docent Jarmo H. Jantunen Professor Helena Sulkala Reviewed by Professor Tuomas Huumo Associate Professor Scott Jarvis Opponent Associate Professor Scott Jarvis ISBN 978-952-62-0113-9 (Paperback) ISBN 978-952-62-0114-6 (PDF) ISSN 0355-3205 (Printed) ISSN 1796-2218 (Online) Cover Design Raimo Ahonen JUVENES PRINT TAMPERE 2013 Spoelman, Marianne, Prior linguistic knowledge matters: The use of the partitive case in Finnish learner language University of Oulu Graduate School; University of Oulu, Faculty of Humanities, Finnish Language, P.O.