Liturgy and Prayer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copy of Copy of Prayers for Pesach Quarantine

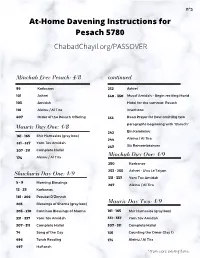

ב"ה At-Home Davening Instructions for Pesach 5780 ChabadChayil.org/PASSOVER Minchah Erev Pesach: 4/8 continued 99 Korbanos 232 Ashrei 101 Ashrei 340 - 350 Musaf Amidah - Begin reciting Morid 103 Amidah Hatol for the summer, Pesach 116 Aleinu / Al Tira insertions 407 Order of the Pesach Offering 353 Read Prayer for Dew omitting two paragraphs beginning with "Baruch" Maariv Day One: 4/8 242 Ein Kelokeinu 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 244 Aleinu / Al Tira 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 247 Six Remembrances 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 174 Aleinu / Al Tira Minchah Day One: 4/9 250 Korbanos 253 - 255 Ashrei - U'va Le'Tziyon Shacharis Day One: 4/9 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 267 Aleinu / Al Tira 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) Maariv Day Two: 4/9 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 74 Song of the Day 136 Counting the Omer (Day 1) 496 Torah Reading 174 Aleinu / Al Tira 497 Haftorah *From a pre-existing flame Shacharis Day Two: 4/10 Shacharis Day Three: 4/11 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 12 - 25 Korbanos 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) 203 - 210 Blessings of Shema & Shema 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 211- 217 Shabbos Amidah - add gray box 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah pg 214 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 "Half" Hallel - Omit 2 indicated 74 Song of -

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim Cantor Sherwood Goffin Faculty, Belz School of Jewish Music, RIETS, Yeshiva University Cantor, Lincoln Square Synagogue, New York City Song has been the paradigm of Jewish Prayer from time immemorial. The Talmud Brochos 26a, states that “Tefillot kneged tmidim tiknum”, that “prayer was established in place of the sacrifices”. The Mishnah Tamid 7:3 relates that most of the sacrifices, with few exceptions, were accompanied by the music and song of the Leviim.11 It is therefore clear that our custom for the past two millennia was that just as the korbanot of Temple times were conducted with song, tefillah was also conducted with song. This is true in our own day as well. Today this song is expressed with the musical nusach only or, as is the prevalent custom, nusach interspersed with inspiring communally-sung niggunim. It once was true that if you wanted to daven in a shul that sang together, you had to go to your local Young Israel, the movement that first instituted congregational melodies c. 1910-15. Most of the Orthodox congregations of those days – until the late 1960s and mid-70s - eschewed the concept of congregational melodies. In the contemporary synagogue of today, however, the experience of the entire congregation singing an inspiring melody together is standard and expected. Are there guidelines for the proper choice and use of “known” niggunim at various places in the tefillot of the Yamim Noraim? Many are aware that there are specific tefillot that must be sung "...b'niggunim hanehugim......b'niggun yodua um'sukon um'kubal b'chol t'futzos ho'oretz...mimei kedem." – "...with the traditional melodies...the melody that is known, correct and accepted 11 In Arachin 11a there is a dispute as to whether song is m’akeiv a korban, and includes 10 biblical sources for song that is required to accompany the korbanos. -

Prager-Shabbat-Morning-Siddur.Pdf

r1'13~'~tp~ N~:-t ~'!~ Ntf1~P 1~n: CW? '?¥ '~i?? 1~~T~~ 1~~~ '~~:} 'tZJ... :-ttli3i.. -·. n,~~- . - .... ... For the sake of the union of the Holy One Blessed Be He, and the Shekhinah I am prepared to take upon myself the mitzvah You Shall Love Your Fellow Person as Yourself V'ahavta l'rey-acha kamocha and by this merit I open my mouth. .I ....................... ·· ./.· ~ I The P'nai Or Shabbat Morning Siddur Second Edition Completed, with Heaven's Aid, during the final days of the count of the Orner, 5769. "Prayer can be electric and alive! Prayer can touch the soul, burst forth a creative celebration of the spirit and open deep wells of gratitude, longing and praise. Prayer can connect us to our Living Source and to each other, enfolding us in love and praise, wonder and gratitude, awe and thankfulness. Jewish prayer in its essence is soul dialogue and calls us into relationship within and beyond. Through the power of words and melodies both ancient and new, we venture into realms of deep emotion and find longing, sorrow ,joy, hope, wholeness, connection and peace. When guided by skilled leaders of prayer and ritual, our complacency is challenged. We break through outworn assumptions about God and ourselves, and emerge refreshed and inspired to meet the challenges OUr lives offer." (-from the DLTI brochure, by Rabbis Marcia Prager and Shawn Israel Zevit) This Siddur was created as a vehicle to explore how traditional and novel approaches to Jewish prayer can blend, so that the experience of Jewish prayer can be renewed, revitalized and deepened. -

Parshat Ki Tetze the 5770-5771 Year Begins

newsletter In This Issue Parshat Ki Tetze HaRav Nebenzahl on Parshat Ki Tetze The 5770-5771 Year Begins Kollel Rennert Dvar Torah by HaRav Aharon Amar There is excitement in the air as Netiv Aryeh welcomes Staff Dvar Torah by Rav the return of Shana Bet students whose first official day Zvi Ron of Yeshiva was Wednesday 8 Elul. We are looking forward Visitor Log, Mazal Tov's, to welcoming Shana Alef this coming Tuesday. This year Tehillim List the Yeshiva will be learning Massechet Baba Batra. We pray for Siyata D'Shmaya in helping all our students grow Join our list in Torah and Yirat Shamayim. Join our mailing list! RBS Shabbaton! Join Attention alumni and friends living in Ramat Beit Shemesh!!! We are proud to announce that the Rosh Yeshiva HaRav Aharon Bina, HaRav Amos Luban, and HaRav Yitzchak Korn will be joining us for an Alumni Shabbaton in RBS! This may be a once in a lifetime experience so be sure not to miss out! Reserve the date: 25th of Elul, Shabbat Parshat Nitzavim Vayelech (September 3rd-4th) Stay tuned for final details on this amazing Shabbat experience!... YNA.EDU | Ask Rav Nebenzahl | Suggestion Box Contact | Alumni Update | Parsha Us Form Archives American Friends of Netiv Aryeh supports our programs. To contribute to American Friends of Netiv Aryeh, please visit http://www.afna.us/donate HaRav Nebenzahl on Parshat Shoftim HaRav Nebenzahl asks that his Divrei Torah are not read during Tefillah or the Rabbi's sermon 1 of 14 newsletter "Ani LeDodi veDodi Li" Chazal allowed themselves to begin Torah discussions on a humorous note (see Shabbat 30b), let us do so as well. -

Sh'ma As Meditation

Shema As Meditation Torah Reflections on Parashat Va’et-hanan Deuteronomy 3:23 – 7:11 13 Av, 5774 August 9, 2014 Our congregation holds a monthly Service of Comfort and Peace for people who are seeking a quiet, prayerful place during a time of illness, grief or anxiety. The ten or so people who attend sit in a circle; together we sing, meditate, pray and share some thoughts from the Torah. An elderly Russian couple attended our most recent service, accompanied by their grandson, a man in his 30’s who-- unlike his grandparents--spoke English. He explained that his worried grandparents were there to pray for another grandchild who was having a crisis in his life. At one point in the service we go around the circle, each person reading one sentence of a prayer in English. Participants are free to pass if they do not wish to read. The grandfather did not seem to understand much of what was happening, but as we went around the circle and it was his turn to read, he closed his eyes and said, “ Shema Yisrael, Adonai Eloheinu, Adonai Ehad .” This man, like so many other Jews throughout the ages, turned to the Shema when all other words failed. We first hear the Shema from Moses as he addresses the Israelites in the Torah portion for this week (Deuteronomy 6:4). Moses realizes that life will not be easy, that the people he leads and their descendants will have many hardships, will experience spiritual and physical exile, will be lost and not know where to turn. -

JEWISH PRINCIPLES of CARE for the DYING JEWISH HEALING by RABBI AMY EILBERG (Adapted from "Acts of Laving Kindness: a Training Manual for Bikur Holim")

A SPECIAL EDITION ON DYING WINTER 2001 The NATIONAL CENTER for JEWISH PRINCIPLES OF CARE FOR THE DYING JEWISH HEALING By RABBI AMY EILBERG (adapted from "Acts of Laving Kindness: A Training Manual for Bikur Holim") ntering a room or home where death is a gone before and those who stand with us now. Epresence requires a lot of us. It is an intensely We are part of this larger community (a Jewish demanding and evocative situation. It community, a human community) that has known touches our own relationship to death and to life. death and will continue to live after our bodies are It may touch our own personal grief, fears and gone-part of something stronger and larger than vulnerability. It may acutely remind us that we, death. too, will someday die. It may bring us in stark, Appreciation of Everyday Miracles painful confrontation with the face of injustice Quite often, the nearness of death awakens a when a death is untimely or, in our judgement, powerful appreciation of the "miracles that are with preventable. If we are professional caregivers, we us, morning, noon and night" (in the language of may also face feelings of frustration and failure. the Amidah prayer). Appreciation loves company; Here are some Jewish principles of care for the we only need to say "yes" when people express dying which are helpful to keep in mind: these things. B'tselem Elohim (created in the image of the Mterlife Divine) Unfortunately, most Jews have little knowledge This is true no matter what the circumstances at of our tradition's very rich teachings on life after the final stage of life. -

PESACH HOLIDAY SCHEDULE 2020 Jewishroc “PRAY-FROM-HOME” April 8 – April 16

PESACH HOLIDAY SCHEDULE 2020 JewishROC “PRAY-FROM-HOME” April 8 – April 16 During these times of social distancing, we encourage everyone to maintain the same service times AT HOME as if services were being held at JewishROC. According to Jewish Law under compelling circumstances, a person who cannot participate in the community service should make every effort to pray at the same time as when the congregation has their usual services. (All page numbers provided below are for the Artscroll Siddur or Chumash used at JewishROC) Deadline for Sale of Chametz Wed. April 1, 5:00 p.m. (Forms must be emailed to [email protected]) Search for Chametz Tues. April 7, 8:12 p.m. – see Siddur page 654 Burning/Disposal of Chametz Wed. April 8, 10:36 a.m. at the latest; recite the third paragraph on page 654 of the Siddur Siyyum for First Born: Tractate Sotah Wed. April 8, 9:00 a.m. - Held Remotely: Register no later than April 1st by sending your Skype address to [email protected]. Wednesday, April 8: Erev Pesach 1st Seder 7:15 a.m. Morning service/Shacharit: Siddur pages 16-118; 150-168. 9:00 a.m. Siyyum for first born; Register no later than April 1st by sending your Skype address to [email protected]. 10:30 a.m. Burning/disposal of Chametz; see page 654 of Artscroll Siddur. Don’t forget to recite the Annulment of the Chametz (third paragraph) 7:15 p.m. Afternoon Service/Mincha: Pray the Daily Minchah, Siddur page 232-248; Conclude with Aleinu 252-254 7:30 p.m. -

Chanting Psalm 118:1-4 in Hallel Aaron Alexander, Elliot N

Chanting Psalm 118:1-4 in Hallel Aaron Alexander, Elliot N. Dorff, Reuven Hammer May, 2015 This teshuvah was approved on May 12, 2015 by a vote of twelve in favor, five against, and one abstention (12-5-1). Voting in Favor: Rabbis Aaron Alexander, Pamela Barmash, Elliot Dorff, Susan Grossman, Reuven Hammer, Joshua Heller, Jeremy Kalmanofsky, Gail Labovitz, Amy Levin, Micah Peltz, Elie Spitz, Jay Stein. Voting Against: Rabbis Baruch Frydman-Kohl, David Hoffman, Adam Kligfeld, Paul Plotkin, Avram Reisner. Abstaining: Rabbi Daniel Nevins. Question: In chanting Psalm 118:1-4 in Hallel, should the congregation be instructed to repeat each line after the leader, or should the congregation be taught to repeat the first line after each of the first four? Answer: As we shall demonstrate below, Jewish tradition allows both practices and provides legal reasoning for both, ultimately leaving it to local custom to determine which to use. As indicated by the prayer books published by the Conservative Movement, however, the Conservative practice has been to follow the former custom, according to which the members of the congregation repeat each of the first four lines of Psalm 118 antiphonally after the leader, and our prayer books should continue to do so by printing the psalm as it is in the Psalter without any intervening lines. However, because the other custom exists and is acceptable, it should be mentioned as a possible way of chanting these verses of Hallel in the instructions. A. The Authority of Custom on this Matter What is clear from the earliest Rabbinic sources is that local customs varied as to how to recite Hallel, and each community was authorized to follow its own custom. -

Tefilot Prayer List

NEVE SHALOM TEFILLOT/PRAYERS GAN –SEVENTH GRADE GAN/KINDERGARTEN-SECOND GRADES Shabbat candles bracha/ Yom Tov, holiday bracha Shalom Aleichem –Only first stanza Kiddush- Bracha only of Borey Pri Hagafen Hamotzi –bracha over all types of bread Mezonote- bracha over baked goods other than bread ie cake, pretzels Ha’etz- bracha over fruit Ha’adamah- bracha over vegetables Sheh Hakol – bracha over drinks, fish, candy and any other foods not listed in above categories SHABBAT TEFILLOT IN SYNAGOGUE FRIDAY NIGHT (GAN – SECOND) Shema Yisrael (out loud), Baruch Shem K’vod…(whisper) V’ahavta V’shamru Bnai Yisrael et HaShabbat…brit Olam Romemu Hashem ….V’hish tachavu L’har Kadsho Oseh Shalom Adon Olam – 1st stanza (learn new stanza every couple of months) SHABBAT MORNING TEFILLOT IN SYNAGOGUE (GAN –SECOND) Modeh Ani Ma Tovu Torah tziva lanu Moshe Shema Yisrael (out loud), Baruch Shem K’vod…(whisper) V’ahavta Adon Olam –(learn 1 new stanza every couple of months) THIRD GRADE Shalom Aleichem- all 4 stanzas L’cha Dodi (verses 1, 2, 3 and last) Sh’ma & V’ahavta Mi Chamocha (Friday night) V’shamru Oseh Shalom Bimromav Adon Olam- all stanzas Ein Keloheinu Kiddush (Friday Night) at least 1st line Birkat Hamazon -1st paragraph Aleinu – Full 1st paragraph and last line in 2nd paragraph-V’ne’emar Hatikvah FOURTH GRADE Kiddush (Friday Night) whole prayer Shalom Aleichem- all 4 stanzas, standard melody L’chu N’ran’na, Yism’chu, Barchu L’cha Dodi (all verses) Sh’ma & V’ahavta (focus on Trop) V’shamru Hatzi Kaddish Ashrei –first 12 lines through Yoducha Hashem al kol ma’asecha Aleinu- 1st full paragraph and last line in 2nd paragraph- V’ne’emar Birkhat Hamazon (1st full paragraph, and all ending brachot/blessings for all consecutive paragraphs ie. -

Parashat Va'etchanan

The Secret to and in health. We are vessels in the hands of God. We are faithful servants, We try to analyze all the reasons for our knowledge, such as our education, prosper.” I would be sitting down, idling, and by chance see that there was God did not choose this people, because they were the most powerful, or He defeated slavery and enslavement and gave us liberty. Word, and to teach them to place the commandments within their hearts. Our thoughts, actions, and dwellings are marked with the word “Shema,” e Plea of Moses instruments of blessing, vessels of honor in the hands of God. languages, mathematics, money management, music, and a thousand some small task that needed to be done. I would get up and do it, and right the most intelligent, or the most successful. the tellin and the mezuzah. We will serve God faithfully. Again and again Moses’ words convince us, our sons, and our son’s sons, to I would like to begin with the rst word of the parasha in Hebrew – dierent studies that try to put our nger on our best-kept secret as Jews. then the commander would pass by and praise me. I helped out for a the Success of If God wants us to continue to serve Him in sickness, so be it; we will serve God chose this people because He swore to our forefathers that He would Yeshua is Our Redeemer learn to memorize, and to keep in mind the laws and commandments of Let us have a Shabbat of peace, blessing, and comfort, especially on this “va’etchanan,” which means “I pleaded”: moment, and I was caught at the very best moment. -

Yom Kippur at Home 5771

Yom Kippur at Home 5771 We will miss davening with you at The Jewish Center this year. We hope that this will help guide you through the Machzor on Rosh HaShanah from your home. When davening without a minyan, one omits Barchu, Kaddish, Kedushah, and Chazarat HaShatz, and the Thirteen Attributes of God during Selichot. There are many beautiful piyyutim throughout Yom Kippur davening as well as the Avodah service in Mussaf that you may want to include after your silent Amidah. You omit the Torah service, but you can read through both the Torah and Haftarah readings. If you would like to borrow a Machzor from The Jewish Center prior to Rosh Hashanah, please use this form https://www.jewishcenter.org/form/Machzor%20Loan%20Program If you have any questions or concerns, or if we can be of assistance to you in any way, please do not hesitate to reach out to us, Rabbi Yosie Levine at [email protected] or Rabbi Elie Buechler at [email protected]. Wishing you a Shanah Tovah, Rabbi Yosie Levine Rabbi Elie Buechler Koren Artscroll Birnbaum Kol Nidre/Ma’ariv Kol Nidre 69-75 58-60 489-491 Shehehayanu 75 60 491 Ma’ariv 81-119 56-98 495-517 Selihot Ya’aleh, Shomei’a tefillah 125-131 102-108 521-427 Selah na Lach. 139-179 112-136 531-557 … Avinu Malkeinu 189-193 144-148 565-570 Aleinu 199-201 152-154 571 Le-David 205 156-158 573-575 Recite at Home Shir ha-Yihud 219-221 166 105-107 Shir ha-Kavod 253-255 188 127-129 Shir Shel Yom/Le-David 461/467 236/238 Adon Olam/Yigdal through Pesukei 471-553 246-320 53-167 de-Zimra -

Addenda to Psalm 145

ADDENDA TO PSALM 145 RAYMOND APPLE Psalm 145, colloquially known as Ashrei, is one of the best known biblical passages in the Jewish liturgy. It occurs three times in the daily prayers, more often than any other psalm. It appears first in the early morning pesukei d’zimra (Passages of Praise); next in the final section of the morning service; and also at the beginning of the afternoon service. This threefold usage fulfils the principle found in TB Berakhot 4b that whoever recites this psalm three times a day is assured of a place in the afterlife. The triple recitation exempli- fies a tendency in Jewish liturgy whereby important phrases and quotations are said more than once, with a preference for three times. TB Berakhot 4b notes that Psalm 145 has two special features to commend it. The first is that, being constructed as an alphabetical acrostic (with the exception of the letter nun),1 it enlists the whole of the aleph-bet to extol the deeds of the Almighty. It should be added, however, that there are several other psalms with alphabetical acrostics. The second is that it articulates the tenet of God’s generosity and providence: You give it openhandedly, feeding every creature to its heart’s content (verse 16; cf. Ps. 104:28, JPSA transla- tion). The Talmud does not call the psalm by its current title of Ashrei, but by its opening words, Tehillah l’David, A song of praise; of (or by, or in the style of) David, arising out of which the name Tehillim (Praises) is applied to the whole psalter.