Addenda to Psalm 145

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Old Testament Psalms in the Book of Mormon

17 Old Testament Psalms in the Book of Mormon John Hilton III he Psalms provide powerful messages of praise and worship . Their words Treverberate not only throughout the Old Testament but also in the New . Elder Jeffrey R . Holland has written that “the book of Psalms may be the one biblical text admired nearly equally by both Christians and Jews, to say noth- ing of those of other faiths—or no faith at all—who find comfort in its verses and encouragement in the hope they convey ”. 1 Over one hundred years ago Franz Delitzsch noted, “Next to the book of Isaiah, no book is so frequently quoted in the New Testament as the Psalter ”. 2 Henry Shires similarly states that “the N[ew] T[estament] has been influenced by Psalms more than by any other book of the O[ld] T[estament] . In 70 cases N T. quotations of Psalms are introduced by formulas . There are 60 more quo- tations that have no introductory formula, and in an additional 220 instances we can discover identifiable citations and references ”.3 These frequent New Testament allusions to the Psalms should not be surprising, for as Robert Alter writes, “Through the ages, Psalms has been the most urgently, personally pres- ent of all the books of the Bible in the lives of many readers ”. 4 John Hilton III is an assistant professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University. 291 292 John Hilton III Given that the Psalms are frequently quoted in the New Testament, one wonders if a similar phenomenon occurs in the Book of Mormon . -

How the Old Testament Came to Us

SUNDAY SCHOOL MATERIALS FOR ADULTS LESSON 3 HOW THE OLD TESTAMENT CAME TO US Scripture Text: Psalm 145:1-13 God began to give His Word to man by speaking to him. He spoke to man in all ages, giving personal commands. When ready to give a system of law for guidance over a length of time, He first spoke it (Exodus 20:1-19), then He wrote part of it with His own finger (Exodus 31:18), then commanded Moses to write thou these words (Exodus 24:4; 34:27), and Moses obeyed. All Old Testament Books were written as God led the writers to write (Jeremiah 30:2; Habakkuk 2:2; 2 Peter 1:21). With few exceptions, they were written in Hebrew on parchment and rolled into scrolls to make a book. These were copied by hand by scribes, an expensive and laborious task. The Old Testament is God's Word, was written to stand forever, and is to be spread to all people. MEMORY VERSE: And the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together: for the mouth of the Lord hath spoken it.—Isaiah 40:5 DAILY READINGS: Mon.—2 Kings 22 Hilkiah finds a Bible. Tue.—2 Kings 23:1-25 Josiah obeys the Bible. Wed.—Isaiah 40:1-11 God's Word and promise will stand. Thu.—Isaiah 45:17-23 Message of salvation for all people. Fri.—Psalm 119:17-32 Prayer for the blessing of God's Word. Devotional Reading: Isaiah 62 Whole world to know of salvation. -

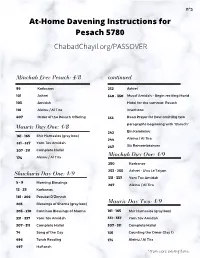

Copy of Copy of Prayers for Pesach Quarantine

ב"ה At-Home Davening Instructions for Pesach 5780 ChabadChayil.org/PASSOVER Minchah Erev Pesach: 4/8 continued 99 Korbanos 232 Ashrei 101 Ashrei 340 - 350 Musaf Amidah - Begin reciting Morid 103 Amidah Hatol for the summer, Pesach 116 Aleinu / Al Tira insertions 407 Order of the Pesach Offering 353 Read Prayer for Dew omitting two paragraphs beginning with "Baruch" Maariv Day One: 4/8 242 Ein Kelokeinu 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 244 Aleinu / Al Tira 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 247 Six Remembrances 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 174 Aleinu / Al Tira Minchah Day One: 4/9 250 Korbanos 253 - 255 Ashrei - U'va Le'Tziyon Shacharis Day One: 4/9 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 267 Aleinu / Al Tira 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) Maariv Day Two: 4/9 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 74 Song of the Day 136 Counting the Omer (Day 1) 496 Torah Reading 174 Aleinu / Al Tira 497 Haftorah *From a pre-existing flame Shacharis Day Two: 4/10 Shacharis Day Three: 4/11 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 12 - 25 Korbanos 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) 203 - 210 Blessings of Shema & Shema 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 211- 217 Shabbos Amidah - add gray box 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah pg 214 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 "Half" Hallel - Omit 2 indicated 74 Song of -

The Mishkan at Central Synagogue Pride Shabbat, June 29, 2019 / 26 Sivan 5779

The Mishkan at Central Synagogue Pride Shabbat, June 29, 2019 / 26 Sivan 5779 (142) Opening Song / Oseh Shalom Supplementary Prayers and Songs: Morning Blessings of Gratitude / Birchot HaShachar We Are Loved / Ahavah Rabah (Shir Waking / Modeh Ani Ya’akov) We are loved, loved, loved Gathering / Mah Tovu By unending love (76) Our Bodies / Asher Yatzar An unending love (78) Our Souls / Elohai Neshama Everyday Miracles / Nisim B’Chol Yom Prayer for Healing (Todd Herzog) Learning Torah El Na, R’fa Na Lah, R’fa Na Lanu Songs of Praise / P’sukei D’Zimrah (98) Psalm 145 / Ashrei--Va’Anachnu Dear God of our ancestors Help us renew our faith (100) Psalm 150 / Hallelujah Grant us a perfect healing The Shema and its Blessings Bring peace to all our days (108) Call to Prayer / Bar’chu Restore our strength of body (110) The Wonder of Creation / Yotzeir Or Help clarify our minds (112) The Loving Gift of Torah / Ahavah Rabbah Refresh our tired spirits (114) Proclaiming God’s Oneness / Shema Rejuvenate our light (116) Love for God’s Teaching / V’ahavta (122) Redemption / Mi Chamocha—Tzur Yisrael Vahasheivota / V’neemar (Shir Ya’akov) Standing Prayer / Tefillah / Amidah Vahasheivota el levav’cha (124) Open our Mouths / Adonai Sefatai Tiftach ki Adonai, Hu HaElohim … V’neemar, v’haya Adonai Avot (126) God of Our Ancestors / L’melech al kol HaAretz (128) Life-Giving and Powerful God / G’vurot Bayom Hahu, yih’yeh Adonai echad (130) Sanctifying God’s Name / Kedushah Ush’mo echad Sanctifying Shabbat / Yis’m’chu or V’Shamru We Give Thanks / Modim Anachnu Lach Prayer for Peace / Sim Shalom May Our Prayers Be Heard / Yih’yu L’ratzon (142) Prayer for Peace / Oseh Shalom Torah Service (248) Words of the Prophets / Haftarah Proclaiming God’s Greatness / Vahasheivota (OOS) Mourners’ Prayer / Kaddish Yatom (294) Closing song / Oseh Shalom (142) . -

Psalms of Praise: “Pesukei Dezimra ”

Dr. Yael Ziegler Pardes The Psalms 1 Psalms of Praise: “Pesukei DeZimra” 1) Shabbat 118b אמר רבי יוסי: יהא חלקי מגומרי הלל בכל יום. איני? והאמר מר: הקורא הלל בכל יום - הרי זה מחרף ומגדף! - כי קאמרינן - בפסוקי דזמרא R. Yosi said: May my portion be with those who complete the Hallel every day. Is that so? Did not the master teach: “Whoever recites the Hallel every day, he is blaspheming and scoffing?” [R. Yosi explained:] When I said it, it was regarding Pesukei DeZimra. Rashi Shabbat 118b הרי זה מחרף ומגדף - שנביאים הראשונים תיקנו לומר בפרקים לשבח והודיה, כדאמרינן בערבי פסחים, )קיז, א(, וזה הקוראה תמיד בלא עתה - אינו אלא כמזמר שיר ומתלוצץ. He is blaspheming and scoffing – Because the first prophets establish to say those chapters as praise and thanks… and he who recites it daily not in its proper time is like one who sings a melody playfully. פסוקי דזמרא - שני מזמורים של הילולים הללו את ה' מן השמים הללו אל בקדשו . Pesukei DeZimra – Two Psalms of Praise: “Praise God from the heavens” [Psalm 148]; “Praise God in His holiness” [Psalm 150.] Massechet Soferim 18:1 Dr. Yael Ziegler Pardes The Psalms 2 אבל צריכין לומר אחר יהי כבוד... וששת המזמורים של כל יום; ואמר ר' יוסי יהא חלקי עם המתפללים בכל יום ששת המזמורים הללו 3) Maharsha Shabbat 118b ה"ז מחרף כו'. משום דהלל נתקן בימים מיוחדים על הנס לפרסם כי הקדוש ברוך הוא הוא בעל היכולת לשנות טבע הבריאה ששינה בימים אלו ...ומשני בפסוקי דזמרה כפירש"י ב' מזמורים של הלולים כו' דאינן באים לפרסם נסיו אלא שהם דברי הלול ושבח דבעי בכל יום כדאמרי' לעולם יסדר אדם שבחו של מקום ואח"כ יתפלל וק"ל: He is blaspheming. -

—Come and See What God Has Done“: the Psalms of Easter*

Word & World 7/2 (1987) Copyright © 1987 by Word & World, Luther Seminary, St. Paul, MN. All rights reserved. page 207 Texts in Context “Come and See What God Has Done”: The Psalms of Easter* FREDERICK J. GAISER Luther Northwestern Theological Seminary, St. Paul, Minnesota “Whenever the Psalter is abandoned, an incomparable treasure vanishes from the Christian church. With its recovery will come unsuspected power.”1 It is possible to agree with Bonhoeffer’s conviction without being naive about the prospect of this happening automatically by a liturgical decision to incorporate the psalms into Sunday morning worship. Not that this is not a good and needed corrective; it is. In many of those worship services the psalms had become nothing more than the source of traditional versicles—little snippets to provide the proper mood of piety in the moments of transition between things that mattered. Yet the Psalter never went away, despite its liturgical neglect. The church called forth psalms in occasional moments of human joy and tragedy, poets paraphrased them for the hymnals, and faithful Christians read and prayed them for guidance and support in their own lives. But now many Christian groups have deliberately re-established the psalms as a constitutive element in regular public worship. What will the effect of this be? Some congregations have found them merely boring-another thing to sit through—which suggests a profound need for creative thinking about how and where to use the psalms so people can hear and participate in the incredible richness and dramatic power of the life within them. -

Complete Song Book (2013 - 2016)

James Block Complete Song Book (2013 - 2016) Contents ARISE OH YAH (Psalm 68) .............................................................................................................................................. 3 AWAKE JERUSALEM (Isaiah 52) ................................................................................................................................... 4 BLESS YAHWEH OH MY SOUL (Psalm 103) ................................................................................................................ 5 CITY OF ELOHIM (Psalm 48) (Capo 1) .......................................................................................................................... 6 DANIEL 9 PRAYER .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 DELIGHT ............................................................................................................................................................................ 8 FATHER’S HEART ........................................................................................................................................................... 9 FIRSTBORN ..................................................................................................................................................................... 10 GREAT IS YOUR FAITHFULNESS (Psalm 92) ............................................................................................................. 11 HALLELUYAH -

Psalm 84 an Old Testament

Psalm 84: an Old Testament ‘Pilgrim’s Progress’. To the chief musician on the Gittith. A Psalm of the sons of Korah. 1. How beloved are your dwelling places, O Lord of hosts! 2. My soul longs, even faints, for the courts of the Lord; my heart and my flesh shout for joy to the living God. 3. Even the sparrow has found a house, and the swallow a nest for herself, where she may lay her young, at your altars, O Lord of hosts, my King and my God. 4. Blessed are those who dwell in your house, they will be still praising you! Selah. 5. Blessed is the man whose strength is in you, in whose heart are the highways to Zion. 6. Passing through the valley of Baca they make it a place of springs; the early rain also covers it with blessings. 7. They go from strength to strength, before appearing before God in Zion. 8. O Lord God of hosts, hear my prayer; give ear, O God of Jacob! Selah. 9. Behold, O God, our shield, and look upon the face of your anointed! 10. For a day in your courts is better than a thousand elsewhere. I would rather be a doorkeeper in the house of my God than dwell in the tents of wickedness. 11. For the Lord God is a sun and shield; the Lord will give grace and glory. No good thing will He withhold from those who walk uprightly. 12. O Lord of hosts, blessed is the man who trusts in you! The title of the psalm associates the psalm with the ‘sons (‘the descendants’, that is) of Korah. -

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim Cantor Sherwood Goffin Faculty, Belz School of Jewish Music, RIETS, Yeshiva University Cantor, Lincoln Square Synagogue, New York City Song has been the paradigm of Jewish Prayer from time immemorial. The Talmud Brochos 26a, states that “Tefillot kneged tmidim tiknum”, that “prayer was established in place of the sacrifices”. The Mishnah Tamid 7:3 relates that most of the sacrifices, with few exceptions, were accompanied by the music and song of the Leviim.11 It is therefore clear that our custom for the past two millennia was that just as the korbanot of Temple times were conducted with song, tefillah was also conducted with song. This is true in our own day as well. Today this song is expressed with the musical nusach only or, as is the prevalent custom, nusach interspersed with inspiring communally-sung niggunim. It once was true that if you wanted to daven in a shul that sang together, you had to go to your local Young Israel, the movement that first instituted congregational melodies c. 1910-15. Most of the Orthodox congregations of those days – until the late 1960s and mid-70s - eschewed the concept of congregational melodies. In the contemporary synagogue of today, however, the experience of the entire congregation singing an inspiring melody together is standard and expected. Are there guidelines for the proper choice and use of “known” niggunim at various places in the tefillot of the Yamim Noraim? Many are aware that there are specific tefillot that must be sung "...b'niggunim hanehugim......b'niggun yodua um'sukon um'kubal b'chol t'futzos ho'oretz...mimei kedem." – "...with the traditional melodies...the melody that is known, correct and accepted 11 In Arachin 11a there is a dispute as to whether song is m’akeiv a korban, and includes 10 biblical sources for song that is required to accompany the korbanos. -

9781845502027 Psalms Fotb

Contents Foreword ......................................................................................................7 Notes ............................................................................................................. 8 Psalm 90: Consumed by God’s Anger ......................................................9 Psalm 91: Healed by God’s Touch ...........................................................13 Psalm 92: Praise the Ltwi ........................................................................17 Psalm 93: The King Returns Victorious .................................................21 Psalm 94: The God Who Avenges ...........................................................23 Psalm 95: A Call to Praise .........................................................................27 Psalm 96: The Ltwi Reigns ......................................................................31 Psalm 97: The Ltwi Alone is King ..........................................................35 Psalm 98: Uninhibited Rejoicing .............................................................39 Psalm 99: The Ltwi Sits Enthroned ........................................................43 Psalm 100: Joy in His Presence ................................................................47 Psalm 101: David’s Godly Resolutions ...................................................49 Psalm 102: The Ltwi Will Rebuild Zion ................................................53 Psalm 103: So Great is His Love. .............................................................57 -

Psalms of Praise: 100 and 150 the OLD TESTAMENT * Week 25 * Opening Prayer: Psalm 100

Psalms of Praise: 100 and 150 THE OLD TESTAMENT * Week 25 * Opening Prayer: Psalm 100 I. “Songs of Ascent” – Psalms 120-134 – II. Psalm 100 A psalm. For giving grateful praise. 1 Shout for joy to the Lord, all the earth. Psalm 33:3 – Sing to [the LORD] a new song; play skillfully, and shout for joy. 2 Worship the Lord with gladness; come before him with joyful songs. 3 Know that the Lord is God. It is he who made us, and we are his (OR “and not we ourselves”) we are his people, the sheep of his pasture. 4 Enter his gates with thanksgiving and his courts with praise; give thanks to him and praise his name. 5 For the Lord is good and his love endures forever; his faithfulness continues through all generations. (See Revelation chapters 4,7,and 19-22) III. Psalm 150 1 Praise the Lord. Praise God in his sanctuary; praise him in his mighty heavens. 2 Praise him for his acts of power; praise him for his surpassing greatness. 3 Praise him with the sounding of the trumpet, praise him with the harp and lyre, 4 praise him with timbrel and dancing, praise him with the strings and pipe, 5 praise him with the clash of cymbals, praise him with resounding cymbals. 6 Let everything that has breath praise the Lord. Praise the Lord. IV. Messianic Psalms A. Psalm 2:1-7 – B. Psalm 22 – Quoted on the cross. C. Psalm 31:5 – Prayer at bedtime. D. Psalm 78:1-2 – “parables.” E. -

The Significance of the Biblical Dead Sea Scrolls

Journal of Theology of Journal Southwestern dead sea scrolls sea dead SWJT dead sea scrolls Vol. 53 No. 1 • Fall 2010 Southwestern Journal of Theology • Volume 53 • Number 1 • Fall 2010 The Significance of the Biblical Dead Sea Scrolls Peter W. Flint Trinity Western University Langley, British Columbia [email protected] Brief Comments on the Dead Sea Scrolls and Their Importance On 11 April 1948, the Dead Sea Scrolls were announced to the world by Millar Burrows, one of America’s leading biblical scholars. Soon after- wards, famed archaeologist William Albright made the extraordinary claim that the scrolls found in the Judean Desert were “the greatest archaeological find of the Twentieth Century.” A brief introduction to the Dead Sea Scrolls and what follows will provide clear indications why Albright’s claim is in- deed valid. Details on the discovery of the scrolls are readily accessible and known to most scholars,1 so only the barest comments are necessary. The discovery begins with scrolls found by Bedouin shepherds in one cave in late 1946 or early 1947 in the region of Khirbet Qumran, about one mile inland from the western shore of the Dead Sea and some eight miles south of Jericho. By 1956, a total of eleven caves had been discovered at Qumran. The caves yielded various artifacts, especially pottery. The most impor- tant find was scrolls (i.e. rolled manuscripts) written in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek, the three languages of the Bible. Almost 900 were found in the Qumran caves in about 25,000–50,000 pieces,2 with many no bigger than a postage stamp.