Chanting Psalm 118:1-4 in Hallel Aaron Alexander, Elliot N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4Q521 and What It Might Mean for Q 3–7

Chapter 20 4Q521 and What It Might Mean for Q 3–7 Gaye Strathearn am personally grateful for S. Kent Brown. He was a commit- I tee member for my master’s thesis, in which I examined 4Q521. Since that time he has been a wonderful colleague who has always encouraged me in my academic pursuits. The relationship between the Dead Sea Scrolls and Christian- ity has fueled the imagination of both scholar and layperson since their discovery in 1947. Were the early Christians aware of the com- munity at Qumran and their texts? Did these groups interact in any way? Was the Qumran community the source for nascent Chris- tianity, as some popular and scholarly sources have intimated,¹ or was it simply a parallel community? One Qumran fragment that 1. For an example from the popular press, see Richard N. Ostling, “Is Jesus in the Dead Sea Scrolls?” Time Magazine, 21 September 1992, 56–57. See also the claim that the scrolls are “the earliest Christian records” in the popular novel by Dan Brown, The Da Vinci Code (New York: Doubleday, 2003), 245. For examples from the academic arena, see André Dupont-Sommer, The Dead Sea Scrolls: A Preliminary Survey (New York: Mac- millan, 1952), 98–100; Robert Eisenman, James the Just in the Habakkuk Pesher (Leiden: Brill, 1986), 1–20; Barbara E. Thiering, The Gospels and Qumran: A New Hypothesis (Syd- ney: Theological Explorations, 1981), 3–11; Carsten P. Thiede, The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Jewish Origins of Christianity (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 152–81; José O’Callaghan, “Papiros neotestamentarios en la cueva 7 de Qumrān?,” Biblica 53/1 (1972): 91–100. -

XIII. the Song of the Sea 27-Aug-06 Exodus 15:1-21 Theme: in Response to God’S Great Salvation, the People of God Worship and Praise Him

Exodus I – Notes XIII. The Song of the Sea 27-Aug-06 Exodus 15:1-21 Theme: In response to God’s great salvation, the people of God worship and praise Him. Key Verses: Exodus 15:1-2 1Then Moses and the children of Israel sang this song to the LORD, and spoke, saying: “I will sing to the LORD, for He has triumphed gloriously! The horse and its rider He has thrown into the sea! 2The LORD is my strength and song, and He has become my salvation; He is my God, and I will praise Him; my father’s God, and I will exalt Him.” Review Last week we studied the actual exodus from Egypt, the initial stages of the journey, and God’s great salvation in the crossing of the Red Sea. The exodus event almost seems anticlimactic, wedged in between the ten plagues and the Red Sea crossing. But everything that happens in the exodus – the death of the firstborn of Egypt, the Passover, the plundering of Egypt, the departure of Israel – occurred exactly in accordance with God’s plan. God leads His triumphant army out of Egypt by a visible display of His Shekinah glory – the pillar of cloud and fire. God’s visible presence reassures His people, guides His people, shelters His people, and protects His people. God’s guidance leads Israel away from the quick road along the sea and instead traces a path into the wilderness. God knew that Israel was not ready for the confrontations that awaited them on the direct route to Canaan. -

American Jewish University 2021-2022 Academic Catalog

American Jewish University 2021-2022 Academic Catalog Table of Contents About AJU .........................................................................................................................................6 History of American Jewish University ..................................................................................................... 7 Mission Statement .................................................................................................................................... 8 Institutional Learning Outcomes............................................................................................................... 8 Who We Are .............................................................................................................................................. 8 Diversity Statement .................................................................................................................................. 9 Accreditation ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Accuracy of Information ........................................................................................................................... 9 Questions and Complaints ........................................................................................................................ 9 Contact American Jewish University ...................................................................................................... -

YUTORAH in PRINT Beshalach 5781

The Marcos and Adina Katz YUTORAH IN PRINT Beshalach 5781 The Meaning of Faith Rabbi Dr. Norman Lamm z”l (Originally delivered January 31, 1953) aith” as a subject for a sermon by a Rabbi seems so and in His servant Moses.” After this profession of Faith in appropriate and so to-be-expected, that it is almost an G-d, Az Yashir Moshe Uv’nei Yisroel, Moses and the children invitation to the congregation to doze off into a gentle of Israel began to sing their famous shirah, their famous FSabbath map. And yet it is a topic which is rarely discussed song of freedom and liberty and gratitude and redemption. from a Traditional Jewish pulpit. It is rarely mentioned Our Rabbis saw some connection between the Faith in G-d because it is taken for granted that those who do come to and the singing of the Song. lo zachu Yisroel lomar shirah al synagogue already have faith. It is an assumption which is, I ha’yam ela bi’zchus emunah, Israel was given the privilege of believe, most correct. But the fact remains that Faith is a very shirah, of song, only because of emunah, their faith and belief hazy concept, and that its causes and effects are not always in G-d. Faith, our Rabbis want to say, is that which makes understood. I believe this sufficient reason, therefore, to invite all of life a song, that which gives it cheer and happiness and you with me in an exploration of the Jewish meaning of Faith. -

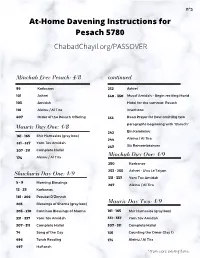

Copy of Copy of Prayers for Pesach Quarantine

ב"ה At-Home Davening Instructions for Pesach 5780 ChabadChayil.org/PASSOVER Minchah Erev Pesach: 4/8 continued 99 Korbanos 232 Ashrei 101 Ashrei 340 - 350 Musaf Amidah - Begin reciting Morid 103 Amidah Hatol for the summer, Pesach 116 Aleinu / Al Tira insertions 407 Order of the Pesach Offering 353 Read Prayer for Dew omitting two paragraphs beginning with "Baruch" Maariv Day One: 4/8 242 Ein Kelokeinu 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 244 Aleinu / Al Tira 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 247 Six Remembrances 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 174 Aleinu / Al Tira Minchah Day One: 4/9 250 Korbanos 253 - 255 Ashrei - U'va Le'Tziyon Shacharis Day One: 4/9 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 267 Aleinu / Al Tira 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) Maariv Day Two: 4/9 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 74 Song of the Day 136 Counting the Omer (Day 1) 496 Torah Reading 174 Aleinu / Al Tira 497 Haftorah *From a pre-existing flame Shacharis Day Two: 4/10 Shacharis Day Three: 4/11 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 12 - 25 Korbanos 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) 203 - 210 Blessings of Shema & Shema 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 211- 217 Shabbos Amidah - add gray box 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah pg 214 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 "Half" Hallel - Omit 2 indicated 74 Song of -

—Come and See What God Has Done“: the Psalms of Easter*

Word & World 7/2 (1987) Copyright © 1987 by Word & World, Luther Seminary, St. Paul, MN. All rights reserved. page 207 Texts in Context “Come and See What God Has Done”: The Psalms of Easter* FREDERICK J. GAISER Luther Northwestern Theological Seminary, St. Paul, Minnesota “Whenever the Psalter is abandoned, an incomparable treasure vanishes from the Christian church. With its recovery will come unsuspected power.”1 It is possible to agree with Bonhoeffer’s conviction without being naive about the prospect of this happening automatically by a liturgical decision to incorporate the psalms into Sunday morning worship. Not that this is not a good and needed corrective; it is. In many of those worship services the psalms had become nothing more than the source of traditional versicles—little snippets to provide the proper mood of piety in the moments of transition between things that mattered. Yet the Psalter never went away, despite its liturgical neglect. The church called forth psalms in occasional moments of human joy and tragedy, poets paraphrased them for the hymnals, and faithful Christians read and prayed them for guidance and support in their own lives. But now many Christian groups have deliberately re-established the psalms as a constitutive element in regular public worship. What will the effect of this be? Some congregations have found them merely boring-another thing to sit through—which suggests a profound need for creative thinking about how and where to use the psalms so people can hear and participate in the incredible richness and dramatic power of the life within them. -

Complete Song Book (2013 - 2016)

James Block Complete Song Book (2013 - 2016) Contents ARISE OH YAH (Psalm 68) .............................................................................................................................................. 3 AWAKE JERUSALEM (Isaiah 52) ................................................................................................................................... 4 BLESS YAHWEH OH MY SOUL (Psalm 103) ................................................................................................................ 5 CITY OF ELOHIM (Psalm 48) (Capo 1) .......................................................................................................................... 6 DANIEL 9 PRAYER .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 DELIGHT ............................................................................................................................................................................ 8 FATHER’S HEART ........................................................................................................................................................... 9 FIRSTBORN ..................................................................................................................................................................... 10 GREAT IS YOUR FAITHFULNESS (Psalm 92) ............................................................................................................. 11 HALLELUYAH -

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim Cantor Sherwood Goffin Faculty, Belz School of Jewish Music, RIETS, Yeshiva University Cantor, Lincoln Square Synagogue, New York City Song has been the paradigm of Jewish Prayer from time immemorial. The Talmud Brochos 26a, states that “Tefillot kneged tmidim tiknum”, that “prayer was established in place of the sacrifices”. The Mishnah Tamid 7:3 relates that most of the sacrifices, with few exceptions, were accompanied by the music and song of the Leviim.11 It is therefore clear that our custom for the past two millennia was that just as the korbanot of Temple times were conducted with song, tefillah was also conducted with song. This is true in our own day as well. Today this song is expressed with the musical nusach only or, as is the prevalent custom, nusach interspersed with inspiring communally-sung niggunim. It once was true that if you wanted to daven in a shul that sang together, you had to go to your local Young Israel, the movement that first instituted congregational melodies c. 1910-15. Most of the Orthodox congregations of those days – until the late 1960s and mid-70s - eschewed the concept of congregational melodies. In the contemporary synagogue of today, however, the experience of the entire congregation singing an inspiring melody together is standard and expected. Are there guidelines for the proper choice and use of “known” niggunim at various places in the tefillot of the Yamim Noraim? Many are aware that there are specific tefillot that must be sung "...b'niggunim hanehugim......b'niggun yodua um'sukon um'kubal b'chol t'futzos ho'oretz...mimei kedem." – "...with the traditional melodies...the melody that is known, correct and accepted 11 In Arachin 11a there is a dispute as to whether song is m’akeiv a korban, and includes 10 biblical sources for song that is required to accompany the korbanos. -

"Who Shall Ascend Into the Mountain of the Lord?": Three Biblical Temple Entrance Hymns

"Who Shall Ascend into the Mountain of the Lord?": Three Biblical Temple Entrance Hymns Donald W. Parry A number of the psalms in the biblical Psalter1 pertain directly to the temple2 and its worshipers. For instance, Psalms 29, 95, and 100 pertain to worshipers who praise the Lord as he sits enthroned in his temple; Psalm 30 is a hymn that was presumably sung at the dedication of Solomon’s temple; Psalms 47, 93, and 96 through 99 are kingship and enthronement psalms that celebrate God’s glory as king over all his creations; Psalms 48, 76, 87, and 122 are hymns that relate to Zion and her temple; Psalm 84 is a pilgrim’s song, which was perhaps sung by temple visitors as soon as they “came within sight of the Holy City”;3 Psalm 118 is a thanksgiving hymn with temple themes; Psalms 120 through 134 are ascension texts with themes pertaining to Zion and her temple, which may have been sung by pilgrims as they approached the temple; and Psalm 150, with its thirteen attestations of “praise,” lists the musical instruments used by temple musicians, including the trumpet, lute, harp, strings, pipe, and cymbals. In all, perhaps a total of one-third of the biblical psalms have temple themes. It is well known that during the days of the temple of Jerusalem temple priests were required to heed certain threshold laws, or gestures of approach, such as anointings, ablutions, vesting with sacred clothing, and sacrices.4 What is less known, however, is the requirement placed on temple visitors to subscribe to strict moral qualities. -

Leave No Song Unsung Beshalach 2013 Shabbat Shirah the Jewish Center Rabbi Yosie Levine

Leave No Song Unsung Beshalach 2013 Shabbat Shirah The Jewish Center Rabbi Yosie Levine I read recently that in China, between 30m and 100m children are currently learning to play the piano or the violin. For those of you keeping score, that number is slightly higher than the number of musically-oriented children here in the United States. In some way, this statistic is surely a measure of the value placed on music by our respective societies. So perhaps we can use this Shabbat Shirah as an opportunity to consider the Jewish value of music and song. Part of what makes Parshat Beshalach so fascinating is that, for the first time, the Torah peels back the veil of naïve obedience that has thus far enshrouded the Jewish people. The initial :leaving Egypt produce images only of compliance and conformity בני ישראל scenes of • The Jewish people are tasked with Korban Pesach. They comply. • They’re asked to despoil the Egyptians of their gold and silver. They do as they’re told. • They’re commanded to march through a barren wasteland toward a destination unknown. They obey without reservation. It’s in our Parsha that a more nuanced picture of the Jewish personality begins to emerge. The trouble is that on the surface this long-awaited moment reveals a temperament that could be said to most closely approximate a kind of schizophrenia. We tend to paint the portrait of the wilderness generation in broad brushstrokes with the themes of ungratefulness, pettiness and grumbling figuring most prominently. But on close inspection, the Torah is communicating something much subtler. -

Psalms of Praise: 100 and 150 the OLD TESTAMENT * Week 25 * Opening Prayer: Psalm 100

Psalms of Praise: 100 and 150 THE OLD TESTAMENT * Week 25 * Opening Prayer: Psalm 100 I. “Songs of Ascent” – Psalms 120-134 – II. Psalm 100 A psalm. For giving grateful praise. 1 Shout for joy to the Lord, all the earth. Psalm 33:3 – Sing to [the LORD] a new song; play skillfully, and shout for joy. 2 Worship the Lord with gladness; come before him with joyful songs. 3 Know that the Lord is God. It is he who made us, and we are his (OR “and not we ourselves”) we are his people, the sheep of his pasture. 4 Enter his gates with thanksgiving and his courts with praise; give thanks to him and praise his name. 5 For the Lord is good and his love endures forever; his faithfulness continues through all generations. (See Revelation chapters 4,7,and 19-22) III. Psalm 150 1 Praise the Lord. Praise God in his sanctuary; praise him in his mighty heavens. 2 Praise him for his acts of power; praise him for his surpassing greatness. 3 Praise him with the sounding of the trumpet, praise him with the harp and lyre, 4 praise him with timbrel and dancing, praise him with the strings and pipe, 5 praise him with the clash of cymbals, praise him with resounding cymbals. 6 Let everything that has breath praise the Lord. Praise the Lord. IV. Messianic Psalms A. Psalm 2:1-7 – B. Psalm 22 – Quoted on the cross. C. Psalm 31:5 – Prayer at bedtime. D. Psalm 78:1-2 – “parables.” E. -

The Babylonian Talmud

The Babylonian Talmud translated by MICHAEL L. RODKINSON Book 10 (Vols. I and II) [1918] The History of the Talmud Volume I. Volume II. Volume I: History of the Talmud Title Page Preface Contents of Volume I. Introduction Chapter I: Origin of the Talmud Chapter II: Development of the Talmud in the First Century Chapter III: Persecution of the Talmud from the destruction of the Temple to the Third Century Chapter IV: Development of the Talmud in the Third Century Chapter V: The Two Talmuds Chapter IV: The Sixth Century: Persian and Byzantine Persecution of the Talmud Chapter VII: The Eight Century: the Persecution of the Talmud by the Karaites Chapter VIII: Islam and Its Influence on the Talmud Chapter IX: The Period of Greatest Diffusion of Talmudic Study Chapter X: The Spanish Writers on the Talmud Chapter XI: Talmudic Scholars of Germany and Northern France Chapter XII: The Doctors of France; Authors of the Tosphoth Chapter XIII: Religious Disputes of All Periods Chapter XIV: The Talmud in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries Chapter XV. Polemics with Muslims and Frankists Chapter XVI: Persecution during the Seventeenth Century Chapter XVII: Attacks on the Talmud in the Nineteenth Century Chapter XVIII. The Affair of Rohling-Bloch Chapter XIX: Exilarchs, Talmud at the Stake and Its Development at the Present Time Appendix A. Appendix B Volume II: Historical and Literary Introduction to the New Edition of the Talmud Contents of Volume II Part I: Chapter I: The Combination of the Gemara, The Sophrim and the Eshcalath Chapter II: The Generations of the Tanaim Chapter III: The Amoraim or Expounders of the Mishna Chapter IV: The Classification of Halakha and Hagada in the Contents of the Gemara.