Additionally, More Attention Might Be Paid to Questions of Audience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

© 2013 Yi-Ling Lin

© 2013 Yi-ling Lin CULTURAL ENGAGEMENT IN MISSIONARY CHINA: AMERICAN MISSIONARY NOVELS 1880-1930 BY YI-LING LIN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral committee: Professor Waïl S. Hassan, Chair Professor Emeritus Leon Chai, Director of Research Professor Emeritus Michael Palencia-Roth Associate Professor Robert Tierney Associate Professor Gar y G. Xu Associate Professor Rania Huntington, University of Wisconsin at Madison Abstract From a comparative standpoint, the American Protestant missionary enterprise in China was built on a paradox in cross-cultural encounters. In order to convert the Chinese—whose religion they rejected—American missionaries adopted strategies of assimilation (e.g. learning Chinese and associating with the Chinese) to facilitate their work. My dissertation explores how American Protestant missionaries negotiated the rejection-assimilation paradox involved in their missionary work and forged a cultural identification with China in their English novels set in China between the late Qing and 1930. I argue that the missionaries’ novelistic expression of that identification was influenced by many factors: their targeted audience, their motives, their work, and their perceptions of the missionary enterprise, cultural difference, and their own missionary identity. Hence, missionary novels may not necessarily be about conversion, the missionaries’ primary objective but one that suggests their resistance to Chinese culture, or at least its religion. Instead, the missionary novels I study culminate in a non-conversion theme that problematizes the possibility of cultural assimilation and identification over ineradicable racial and cultural differences. -

Struggle, #120, March 2006

STRUGGLE A MARXIST APPROACH TO AOTEAROA/NEW ZEALAND No: 120 : $1.50 : March 2006 Super-size My Pay Mobilise to End Youth Rates and Demand $12 Minimum Now In the face of widespread demands for an they rose by 28.8% in Australia, 39.5% end to age poverty, the Clark regime’s cob- in Canada, 46.9% in UK and 68.2% bled coalition has said it wants to raise the Finland. minimum wage to $12.00 per hour by the end of 2008 if ‘economic conditions per- • During the same two decades corporate mit’. But 2008 is too late for low paid and profits went from 34% of GDP to 46%. minimum wage workers - there is already a Wages as a share of GDP fell from 57% low wage crisis despite recent growth in the 42%. economy and record corporate profits. • Australian average wages are 30% high- The Unite union reports that tens of thou- er than NZ now when they were the sands of workers live on the current mini- same as NZ twenty years ago mum wage of $9.50 an hour for those 18 and older and $7.60 an hour for 16 and 17 Poverty-wages are increasing the gap year olds. There is no minimum wage for between rich and poor and increasing other those 15 and under. social inequalities. The majority of low paid and minimum wage workers are women, Compare that to Australia where the mini- Maori, pacific nation peoples, disabled, mum wage is $NZ13.85, nearly 50% higher youth, students and new migrants. -

Waldron Spring 2014

University of Pennsylvania Department of History History 412 The Republic of China, 1911-1949 and After Professor Arthur Waldron Spring 2014 Summary: This seminar treats the history, politics, and culture of the Republic of China, which ruled China from 1911/12 until its overthrow by the Communists in the Civil War (1945-49) who established a new state, the People’s Republic of China (1949-). This was a time of political contention, considerable progress in education, the economy, and other areas: also of comparative openness compared to what followed. After 1931, however, all was dominated by the menace of Japan, which exploded into full scale warfare in 1937-1945. The course consists of readings, seminar discussions, and a research paper. We meet from 3:00-6:00 on Thursdays in Meyerson Hall B-6. Introduction: The last of the traditional dynasties that had ruled China for millennia, the Qing, was overthrown by a series of uprisings that began in October of 1911, It abdicated on February 24, 1912, and was succeeded by the Republic of China, which ruled China until 1949. Its history is fascinating and full of questions. How does a society that has had an emperor for thousands of years set up a new form of government? How do people, who have long operated in accord with well defined “traditions” in everything from the arts to family organization, become “modern”? In fact, for a long time, many believed that was impossible without a revolution like that which created the Soviet Union in 1917. What sorts of literature, arts, fashion, etiquette, and so forth could be both “Chinese” and “modern”? (Again, many have thought this impossible). -

Chinese Women in the Early Twentieth Century: Activists and Rebels

Chinese Women in the Early Twentieth Century: Activists and Rebels Remy Lepore Undergraduate Honors Thesis Department of History University of Colorado, Boulder Defended: October 25th, 2019 Committee Members: Primary Advisor: Timothy Weston, Department of History Secondary Reader: Katherine Alexander, Department of Chinese Honors Representative: Miriam Kadia, Department of History Abstract It is said that women hold up half the sky, but what roles do women really play and how do they interact with politics and society? In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries Chinese women reacted in a variety of ways to the social and political changes of the era. Some women were actively engaged in politics while others were not. Some women became revolutionaries and fought for reform in China, other women were more willing to work with and within the established cultural framework. Discussion of reforms and reformers in the late nineteenth-early twentieth centuries are primarily focused on men and male activism; however, some women felt very strongly about reform and were willing to die in order to help China modernize. This thesis explores the life experiences and activism of five women who lived at the end of China’s imperial period and saw the birth of the Republican period. By analyzing and comparing the experiences of Zheng Yuxiu, Yang Buwei, Xie Bingying, Wang Su Chun, and Ning Lao Taitai, this thesis helps to unlock the complex and often hidden lives of Chinese women in modern Chinese history. Lepore 1 Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………..……… 2 Part 1 ………………………………………………………………………………….………… 4 Historiography ……………………………………………………………………………4 Historical Context …………………………..…………………………………………… 8 Part 2: Analysis …………………………………..…………………………..………………. -

Distribution Agreement

Distribution Agreement In presenting this thesis or dissertation as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis or dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, including display on the world wide web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis or dissertation. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis or dissertation. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. Signature: _____________________________ ______________ Haipeng Zhou Date “Expressions of the Life that is within Us” Epistolary Practice of American Women in Republican China By Haipeng Zhou Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Institute of the Liberal Arts _________________________________________ [Advisor’s signature] Catherine Ross Nickerson Advisor _________________________________________ [Advisor’s signature] Kimberly Wallace-Sanders Advisor _________________________________________ [Member’s signature] Rong Cai Committee Member Accepted: _________________________________________ Lisa A. Tedesco, Ph.D. Dean of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies ___________________ Date “Expressions of the Life that is within Us” Epistolary Practice of American Women in Republican China By Haipeng Zhou M.A., Beijing Foreign Studies -

Ida Pruitt (1888-1985) by Marjorie King Gregory Rohlf University of the Pacific, [email protected]

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons College of the Pacific aF culty Articles All Faculty Scholarship Fall 9-1-2007 Review of China’s American Daughter: Ida Pruitt (1888-1985) by Marjorie King Gregory Rohlf University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/cop-facarticles Part of the Asian History Commons, and the East Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Rohlf, G. (2007). Review of China’s American Daughter: Ida Pruitt (1888-1985) yb Marjorie King. China Review International, 14(2), 484–486. DOI: 10.1353/cri.0.0104 https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/cop-facarticles/10 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the All Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of the Pacific aF culty Articles by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. &KLQD V$PHULFDQ'DXJKWHU,GD3UXLWW ² UHYLHZ *UHJ5RKOI &KLQD5HYLHZ,QWHUQDWLRQDO9ROXPH1XPEHU)DOOSS 5HYLHZ 3XEOLVKHGE\8QLYHUVLW\RI+DZDL L3UHVV '2, KWWSVGRLRUJFUL )RUDGGLWLRQDOLQIRUPDWLRQDERXWWKLVDUWLFOH KWWSVPXVHMKXHGXDUWLFOH Access provided by University of the Pacific (18 Nov 2016 01:25 GMT) 484 China Review International: Vol. 14, No. 2, Fall 2007 5. Unlike Jia, I have translated you as “obtain” rather than “exist” or “existence” to better capture the senses of both “being” and “having” carried by the Chinese term, and to suggest a shift away from the ontology of individual beings implied by Western discourses on existence and toward a relational ontology more compatible with both classical Chinese thought and Bud- dhism. -

Searchable PDF Format

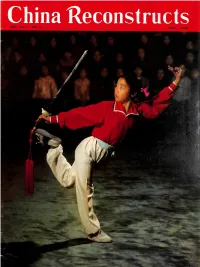

f V •.4BU. L' - •. r \ M '/ MS f tf- Ml- MA S s 1 i ... VOL. XXI NO. 6 JUNE 1972 PUBLISHED MONTHLY IN ENGLISH, FRENCH, SPANISH, ARABIC AND RUSSIAN BY THE CHINA WELFARE INSTITUTE (SOONG CHING LING, CHAIRMAN) CONTENTS EDGAR SNOW —IN MEMORIAM Soong Ching Ling 2 EDGAR SNOW (Poem) Rewi Alley 3 A TRIBUTE Ma Hai-teh {Dr. George Hatem) 4 HE SAW THE RED STAR OVER CHINA Talitha Gerlach 6 TSITSIHAR SAVES ITS FISH Lung Chiang-wen 8 A CHEMICAL PLANT FIGHTS POLLUTION 11 THE LAND OF BAMBOO 14 REPORT FROM TIBET: LINCHIH TODAY 16 HOW WE PREVENT AND TREAT OCCUPA TIONAL DISEASES 17 WHO INVENTED PAPER? 20 LANGUAGE CORNER: LOST AND FOUND 21 JADE CARVING 22 STEELWORKERS TAP HIDDEN POTENTIAL An Tung 26 WHAT I LEARNED FROM THE WORKERS AND PEASANTS Tsien Ling-hi 30 COVER PICTURES: YOUTH AMATEUR ATHLETIC SCHOOL 33 Front: Traditional sword- play by a student of wushu CHILDREN AT WUSHU 34 at the Peking Youth THEY WENT TO THE COUNTRY 37 Amateur Athletic School {see story on p. 33). GEOGRAPHY OF CHINA: LAKES 44 Inside front: Before the OUR POSTBAG 48 puppets go on stage. Back: Sanya Harbor, Hoi- nan Island. Inside back: On the Yu- Editorial Office: Wai Wen Building, Peking (37), China. shui River, Huayuan county, Cable: "CHIRECON" Peking. General Distributor: Hunan province. GUOZI SHUDIAN, P.O. Box 399, Peking, China. EDGAR SNOW-IN MEMORIAM •'V'^i»i . Chairman Mao and Edgar Snow in north Shcnsi, 1936. 'P DGAR SNOW, the life-long the river" and seek out the Chinese that today his book stands up well •*-' friend of the Chinese people, revolution in its new base. -

New Zealand's China Policy

澳大利亚-中国关系研究院 NEW ZEALAND’S CHINA POLICY Building a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership July 2015 FRONT COVER IMAGE: Chinese President Xi Jinping shakes hands with New Zealand’s Prime Minister John Key at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, March 19 2014. © AAP Photo Published by the Australia-China Relations Institute (ACRI) Level 7, UTS Building 11 81 - 115 Broadway, Ultimo NSW 2007 t: +61 2 9514 8593 f: +61 2 9514 2189 e: [email protected] © The Australia-China Relations Institute (ACRI) 2015 ISBN 978-0-9942825-1-4 The publication is copyright. Other than for uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without attribution. CONTENTS List of Figures 4 List of Tables 5 Acknowledgements 5 Executive Summary 6 The Historical Context 11 Politics Above All Else 17 Early Days 17 The Pace Quickens 21 Third-country relations 29 Defence and Security 33 New Zealand’s Military Responses to China 34 To The Future 38 Economic and Trade Relations 41 A Larger Share of Global Trade 41 Free Trade Agreements 42 Merchandise Trade 48 Trade in Services 52 Investment Flows 52 Chinese Students in New Zealand 60 Tourism 62 Lessons from the New Zealand-China FTA 64 People 70 Immigration 70 Chinese Language in New Zealand 72 People-To-People 74 Conclusion 75 About The Centre 76 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: New Zealand-China Exports and Imports (1972-2014) 48 Figure 2: Top Six Sources of New Zealand 49 Merchandise Imports (2000-13) Figure 3: Top Six Destinations for New Zealand 50 Merchandise Exports (2000-13) Figure 4: -

China's Smiling Face to the World: Beijing's English

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CHINA’S SMILING FACE TO THE WORLD: BEIJING’S ENGLISH-LANGUAGE MAGAZINES IN THE FIRST DECADE OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC Leonard W. Lazarick, M.A. History Directed By: Professor James Z. Gao Department of History In the 1950s, the People’s Republic of China produced several English-language magazines to inform the outside world of the remarkable transformation of newly reunified China into a modern and communist state: People’s China, begun in January 1950; China Reconstructs, starting in January 1952; and in March 1958, Peking Review replaced People’s China. The magazines were produced by small staffs of Western- educated Chinese and a few experienced foreign journalists. The first two magazines in particular were designed to show the happy, smiling face of a new and better China to an audience of foreign sympathizers, journalists, academics and officials who had little other information about the country after most Western journalists and diplomats had been expelled. This thesis describes how the magazines were organized, discusses key staff members, and analyzes the significance of their coverage of social and cultural issues in the crucial early years of the People’s Republic. CHINA’S SMILING FACE TO THE WORLD: BEIJING’S ENGLISH-LANGUAGE MAGAZINES IN THE FIRST DECADE OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC By Leonard W. Lazarick Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2005 Advisory Committee: Professor James Z. Gao, Chair Professor Andrea Goldman Professor Lisa R. -

K0617 Hugh Gordon Deane, Jr. (1916-2001) Papers 1936-1998 3 Cubic Feet

THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI RESEARCH CENTER-KANSAS CITY K0617 Hugh Gordon Deane, Jr. (1916-2001) Papers 1936-1998 3 cubic feet Personal papers of journalist, author, and co-founder of the US-China Peoples Friendship Association. Includes correspondence, research notes, publications, conference transcripts, an FBI file on Indusco, manuscripts (published and unpublished), clippings, and a military map drawn by Zhou Enlai. BIOGRAPHY: Hugh Deane began his association with China in 1936 when he was a Harvard exchange student at Lingnan University. After graduating, he returned to China for several years and wrote articles for the Christian Science Monitor and the Springfield (MA) Union and Republican. During World War II, Deane worked for the Coordinator of Information (later the Office of War Information), and then as a naval intelligence officer on MacArthur’s staff in the South Pacific. From 1946 to 1950, he was a Tokyo-based correspondent, writing for a variety of publications on topics concerning eastern Asia, especially the origins of the Korean War. Blacklisted during the McCarthy era, Deane operated laundromats for a short time. In 1960, Deane began an editorial job for the paper Hotel Voice, working as chief editor most of the time until his retirement in 1986. Deane was a founder of the US-China Peoples Friendship Association, and continued to write articles and books until his death on June 25, 2001. PROVENANCE: The papers were donated by Hugh Deane Jr. and accessioned as KA0751 on May 12, 1993; KA0759 on July 22, 1993; KA0802 on April 8, 1994; KA0862 on June 6, 1995; and KA0998 on July 24, 1998. -

Foreigners Under Mao

Foreigners under Mao Western Lives in China, 1949–1976 Beverley Hooper Hong Kong University Press Th e University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © 2016 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8208-74-6 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Cover images (clockwise from top left ): Reuters’ Adam Kellett-Long with translator ‘Mr Tsiang’. Courtesy of Adam Kellett-Long. David and Isobel Crook at Nanhaishan. Courtesy of Crook family. George H. W. and Barbara Bush on the streets of Peking. George Bush Presidential Library and Museum. Th e author with her Peking University roommate, Wang Ping. In author’s collection. E very eff ort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. Th e author apologizes for any errors or omissions and would be grateful for notifi cation of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co., Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents Acknowledgements vii Note on transliteration viii List of abbreviations ix Chronology of Mao’s China x Introduction: Living under Mao 1 Part I ‘Foreign comrades’ 1. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 358 003 SO 022 945 TITLE Fulbright

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 358 003 SO 022 945 TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program, 1992. China: Tradition and Transformation (Curriculum Projects). INSTITUTION National Committee on United States-China Relations, New York, N.Y. SPONS AGENCY Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE [Jan 93] NOTE 620p.; Compiled by the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations on behalf of the United States Department of Education in fulfillment of Fulbright-Hays requirements. For previous proceedings, see ED 340 644, ED 348 327, and ED 348 322-326. Contains wide variety of text excerpted from published sources. PUB TYPE Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MF03/PC25 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Asian Studies; Cross Cultural Studies; *Cultural Awareness; Cultural Exchange; *Developing Nations; Economics Education; Elementary Secondary Education; Females; Foreign Countries; Geography Instruction; Higher Education; Interdisciplinary Approach; International Relations; Multicultural Education; Socialism; Social Studies; Units of Study IDENTIFIERS *China; Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program ABSTRACT This collection of papers is from a seminar on China includes the following papers: "Women in China: A Curriculum Unit" (Mary Ann Backiel); "Education in Mainland China" (Deanna D. Bartels; Felicia C. Eppley); "From the Great Wall to the Bamboo Curtain: China The Asian Giant An Integrated Interdisciplinary Unit for Sixth Grade Students" (Chester Browning); Jeanne-Marie Garcia's "China: Content-Area Lessons for Students of English as a Second Language"; "Daily Life in China under a Socialist Government" (Janet Gould); "Geography Lesson Plan for Ninth Grade Students" (Elizabethann E. Grady); "A Journey through Three Chinas" (Donald 0. Greene); "Modern China: An Introduction to Issues" (Dennis Gregg); "China: Global Studies Curriculum" (Russell Y.