The American Action Painters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art in 1960S

Abstract Expressionism 1940s-1960s A form of abstract art that emphasized spontaneous, intuitive creation of unstructured expressions of the artist’s unconscious Action Painting: emphasized the dynamic handling of paint and techniques that were partly dictated by chance. The act of painting was as significant as the finished work: Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning Jackson Pollock, Blue Poles, 1952 William de Kooning, Untitled, 1975 Color-Field Painting: used large, soft-edged fields of flat color: Mark Rothko, Ab Reinhardt Mark Rothko, Lot 24, “No. 15,” 1952 “A square (neutral, shapeless) canvas, five feet wide, five feet high…a pure, abstract, non- objective, timeless, spaceless, changeless, relationless, disinterested painting -- an object that is self conscious (no unconsciousness), ideal, transcendent, aware of no thing but art (absolutely no anti-art). Ad Reinhardt, Abstract Painting,1963 –Ad Reinhardt Minimalism 1960s rejected emotion of action painters sought escape from subjective experience downplayed spiritual or psychological aspects of art focused on materiality of art object used reductive forms and hard edges to limit interpretation tried to create neutral art-as-art Frank Stella rejected any meaning apart from the surface of the painting, what he called the “reality effect.” Frank Stella, Sunset Beach, Sketch, 1967 Frank Stella, Marrakech, 1964 “What you see is what you see” -- Frank Stella Postminimalism Some artists who extended or reacted against minimalism: used “poor” materials such felt or latex emphasized process and concept rather than product relied on chance created art that seemed formless used gravity to shape art created works that invaded surroundings Robert Morris, Felt, 1967 Richard Serra, Cutting Device: Base Plat Measure, 1969 Hang Up (1966) “It was the first time my idea of absurdity or extreme feeling came through. -

CUBISM and ABSTRACTION Background

015_Cubism_Abstraction.doc READINGS: CUBISM AND ABSTRACTION Background: Apollinaire, On Painting Apollinaire, Various Poems Background: Magdalena Dabrowski, "Kandinsky: Compositions" Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art Background: Serial Music Background: Eugen Weber, CUBISM, Movements, Currents, Trends, p. 254. As part of the great campaign to break through to reality and express essentials, Paul Cezanne had developed a technique of painting in almost geometrical terms and concluded that the painter "must see in nature the cylinder, the sphere, the cone:" At the same time, the influence of African sculpture on a group of young painters and poets living in Montmartre - Picasso, Braque, Max Jacob, Apollinaire, Derain, and Andre Salmon - suggested the possibilities of simplification or schematization as a means of pointing out essential features at the expense of insignificant ones. Both Cezanne and the Africans indicated the possibility of abstracting certain qualities of the subject, using lines and planes for the purpose of emphasis. But if a subject could be analyzed into a series of significant features, it became possible (and this was the great discovery of Cubist painters) to leave the laws of perspective behind and rearrange these features in order to gain a fuller, more thorough, view of the subject. The painter could view the subject from all sides and attempt to present its various aspects all at the same time, just as they existed-simultaneously. We have here an attempt to capture yet another aspect of reality by fusing time and space in their representation as they are fused in life, but since the medium is still flat the Cubists introduced what they called a new dimension-movement. -

Intermediate Painting: Impression, Surrealism, & Abstract

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Course Outlines Curriculum Archive 5-2017 Intermediate Painting: Impression, Surrealism, & Abstract Jessica Agustin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/art-course-outlines Recommended Citation Agustin, Jessica, "Intermediate Painting: Impression, Surrealism, & Abstract" (2017). Course Outlines. 7. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/art-course-outlines/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Curriculum Archive at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Course Outlines by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLASS TITLE: Intermediate Painting DATE: 01/19/2017 SITE: CIM- C Yard TEACHING ARTIST: Jessica Revision to Current Class OVERVIEW OF CLASS In this course, participants will investigate different forms of painting through discussion and art historical examples. Participants will practice previously learned technical skills to explore more conceptual themes in their paintings. At the same time, participants will also learn to experiment with various formal/technical aspects of painting. Intermediate Painting will constitute of a lot of brainstorming, sketching (if needed) and Studio Time and reflection/discussion. ESSENTIAL QUESTION OR THEME What are some of art movements that have influenced art making/painting and how can we apply them to our work? STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES These should include at least 3 of the 4 areas: • Technical/ skill o Participants will use their technical skills to build their conceptual skills. • Creativity/ imagination o Participants will learn to take inspiration from their surroundings. o Participants will learn about different types of art styles/movement that will get them out of their comfort zone and try new techniques. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School College Of

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Arts and Architecture CUT AND PASTE ABSTRACTION: POLITICS, FORM, AND IDENTITY IN ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONIST COLLAGE A Dissertation in Art History by Daniel Louis Haxall © 2009 Daniel Louis Haxall Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2009 The dissertation of Daniel Haxall has been reviewed and approved* by the following: Sarah K. Rich Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Leo G. Mazow Curator of American Art, Palmer Museum of Art Affiliate Associate Professor of Art History Joyce Henri Robinson Curator, Palmer Museum of Art Affiliate Associate Professor of Art History Adam Rome Associate Professor of History Craig Zabel Associate Professor of Art History Head of the Department of Art History * Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT In 1943, Peggy Guggenheim‘s Art of This Century gallery staged the first large-scale exhibition of collage in the United States. This show was notable for acquainting the New York School with the medium as its artists would go on to embrace collage, creating objects that ranged from small compositions of handmade paper to mural-sized works of torn and reassembled canvas. Despite the significance of this development, art historians consistently overlook collage during the era of Abstract Expressionism. This project examines four artists who based significant portions of their oeuvre on papier collé during this period (i.e. the late 1940s and early 1950s): Lee Krasner, Robert Motherwell, Anne Ryan, and Esteban Vicente. Working primarily with fine art materials in an abstract manner, these artists challenged many of the characteristics that supposedly typified collage: its appropriative tactics, disjointed aesthetics, and abandonment of ―high‖ culture. -

Modern & Contemporary

MODERN & CONTEMPORARY ART HÔTEL METROPOLE MONACO 27 NOVEMBER 2018 Above : EUGÈNE BOUDIN (Honfleur 1824 - Deauville 1898) View on the port of Dieppe (Lot 908) Front Cover : СY TWOMBLY Poster Study for ‘Nine Discourses on Commodus by Cy Twombly at Leo Castelli’ 1964 (Lot 912) Back Cover : LÉONARD TSUGUHARU FOUJITA Détail Grande composition 2, dite Composition au chien, 1928. Reliefography on Canvas (Lot 939) Sans titre-1 1 26/09/2017 11:33:03 PAR LE MINISTERE DE MAITRE CLAIRE NOTARI HUISSIER DE JUSTICE A MONACO PRIVATE COLLECTIONS RUSSIAN ART & RARE BOOKS SESSION 1 / PRIVATE COLLECTIONS FRIDAY NOVEMBER 23, 2018 - 14:00 SESSION 2 / RUSSIAN ART FRIDAY NOVEMBER 23, 2018 - 17:00 SESSION 3 / OLD MASTERS SATURDAY NOVEMBER 24, 2018 - 14:00 SESSION 4 / ANTIQUE ARMS & MILITARIA SATURDAY NOVEMBER 24, 2018 - 16:00 SESSION 5 / NUMISMATICS & OBJECTS OF VERTU SATURDAY NOVEMBER 24, 2018 - 17:00 SESSION 6 / MODERN & CONTEMPORARY ART TUESDAY NOVEMBER 27, 2018 - 19:00 Hotel Metropole - 4 avenue de la Madone - 98000 MONACO Exhibition Preview : THURSDAY NOVEMBER 22, 2018 AT 18:00 Exhibition : FRIDAY NOV 23 & SATURDAY NOV 24 10:00 - 13:00 MODERN & CONTEMPORARY : SUNDAY NOV 25 & MONDAY NOV 26 12:00 - 16:00 CONTEMPORARY COCKTAIL : TUESDAY NOV 27 18:00 Inquiries - tel: +377 97773980 - Email: [email protected] 25, Avenue de la Costa - 98000 Monaco Tel: +377 97773980 www.hermitagefineart.com Sans titre-1 1 26/09/2017 11:33:03 SPECIALISTS AND AUCTION ENQUIRIES Alessandro Conelli Ivan Terny President C.E.O. Elena Efremova Ekaterina Tendil Director Head of European Departement Contact : Tel: +377 97773980 Fax: +377 97971205 [email protected] Victoria Matyunina Julia Karpova PR & Event Manager Art Director TRANSPORTATION Catalogue Design: Hermitage Fine Art expresses our gratude to Natasha Cheung, Camille Maréchaux Morgane Cornu and Julia Karpova for help with preparation of cataloguing notes. -

Nv Steam Conference Action Painting

NV STEAM CONFERENCE OBJECTIVE: ACTION PAINTING | ART LAB Students will be able to develop skills in multiple art making techniques through an exploration of forces GRADE: 2 and motion. GRADE: 2 (written for Grade 2 but can easily be VOCABULARY: adapted for older or younger students) Abstract Expressionism: A school of painting that flourished after World War II until the early 1960s, characterized by the view that art is STANDARDS: nonrepresentational and chiefly improvisational. ART: VA:Cr2.1.5a Experiment and develop skills in Composition: The organization and bringing together of multiple art making techniques and approaches constituent visual elements (lines, shapes, colors, through practice. textures, forms, and space) to collectively create a painting or photograph. SCIENCE: Disciplinary core ideas: PS2.A: Forces and Motion. Pushing or pulling on an object can change the Visual Movement: when forms, values, patterns, lines, speed or direction of its motion and can start or stop it. shapes, or colors seem to create action. 2.19.2019 MATERIALS: 4 large trays or baking sheets Large sheets of paper or newsprint • Large sheets of paper or newsprint Washable acrylic paint in at least two contrasting colors • Washable acrylic paint in at least two Wet wipes contrasting colors • Liquid Watercolors in a variety of colors • Craft pom poms Station 3: • Bowls (to hold water and watercolor paint) • Large robot arena (3 x 5 feet) Robot arena • Sphero Large sheets of paper • Sphero nubby cover Washable acrylic paint in at least two contrasting colors • Smart phone or tabled with Sphero App Sphero downloaded (https://edu.sphero.com/d) Nubby Cover for Sphero • Marbles or Ball Bearings Smart phone or tablet with Sphero App downloaded Wet wipes • Large trays or baking sheets • Pencils • Wet Wipes LESSON: • Two drop cloths • Three station wash set-up for cleaning ENGAGEMENT: supplies • Poster or printouts of a Joan Mitchell and a Have the students observe the condition of the room Jackson Pollock painting and the organized supplies. -

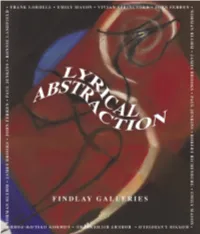

Lyrical Abstraction

Lyrical Abstraction Findlay Galleries presents the group exhibition, Lyrical Abstraction, showcasing works by Mary Abbott, Norman Bluhm, James Brooks, John Ferren, Gordon Onslow Ford, Paul Jenkins, Ronnie Landfield, Frank Lobdell, Emily Mason, Irene Rice Pereira, Robert Richenburg, and Vivian Springford. The Lyrical Abstraction movement emerged in America during the 1960s and 1970s in response to the growth of Minimalism and Conceptual art. Larry Aldrich, founder of the Aldrich Museum, first coined the term Lyrical Abstraction and staged its first exhibition in 1971 at The Whitney Museum of American Art. The exhibition featured works by artists such as Dan Christensen, Ronnie Landfield, and William Pettet. David Shirey, a New York Times critic who reviewed the exhibition, said, “[Lyrical Abstraction] is not interested in fundamentals and forces. It takes them as a means to an end. That end is beauty...” Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings and Mark Rothko’s stained color forms provided important precedence for the movement in which artists adopted a more painterly approach with rich colors and fluid composition. Ronnie Landfield, an artist at the forefront of Lyrical Abstraction calls it “a new sensibility,” stating: ...[Lyrical Abstraction] was painterly, additive, combined different styles, was spiritual, and expressed deep human values. Artists in their studios knew that reduction was no longer necessary for advanced art and that style did not necessarily determine quality or meaning. Lyrical Abstraction was painterly, loose, expressive, ambiguous, landscape-oriented, and generally everything that Minimal Art and Greenbergian Formalism of the mid-sixties were not. Building on Aldrich’s concept of Lyrical Abstractions, Findlay Galleries’ exhibition expands the definition to include artists such as John Ferren, Robert Richenburg and Frank Lobdell. -

Art Is My Natural World: Alison Weld, 1980-2009 Art Is My Natural World: Alison Weld, 1980 - 2009

Art Is My Natural World: Alison Weld, 1980-2009 Art Is My Natural World: Alison Weld, 1980 - 2009 “I Am Nature, She Said” Leslie Luebbers, PhD Electronic publication for the exhibition presented at the Art Museum of the University of Memphis, March 6 - April 17, 2010 All rights reserved. Designed by Christine Virost Cover image: “Tiepolo’s Dream” 2002 oil on linen and Richloom © fabric on canvas 66 x 38 inches An Equal Opportunity/Affirmative Action University I Am Nature, She Said In his 1936 catalog for Cubism and Abstract Art, the first major exhibition of abstract art in America, Alfred Barr, founder of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, wrote: At the grave risk of oversimplification the impulse towards abstract art during the past fifty years may be divided historically into two main currents….The first…may be described as intellectual, structural, architectonic, geometrical, rectilinear and classical in its austerity and dependence upon logic and calculation. The second…is intuitional and emotional rather than intellectual; organic or biomorphic rather than geometrical in its forms; curvilinear rather than rectilinear, decorative rather than structural, and romantic rather than classical in its exaltation of the mystical, the spontaneous and the irrational.i Barr was writing about European abstraction of the early 20th century, and although since that time a strong spiritual motivation has been recognized in some geometric abstraction, his description of “intuitional” abstraction remains valid. In mid-century America, the formalist critic and theorist Clement Greenberg proposed that art forms are most powerful when restricted to their essential components, in the case of painting to a mark-making substance, most commonly paint, and a support, most commonly canvas. -

Effects of Cubism on American Painting Since 1914

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses 1968 Effects of Cubism on American Painting Since 1914 Carl W. Brodin Central Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Art Education Commons Recommended Citation Brodin, Carl W., "Effects of Cubism on American Painting Since 1914" (1968). All Master's Theses. 811. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/811 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EFFECTS OF CUBISM ON AMERICAN PAINTING SINCE 1914 A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty Central Washington State College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Education by Carl W. Brodin August, 1968 . ,0.1 -y;J \':fjcl'i> APPROVED FOR THE GRADUATE FACULTY ________________________________ Edward C. Haines, COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN _________________________________ Louis A. Kollmeyer _________________________________ Alexander H. Howard, Jr. TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. THE PROBLEM AND DEFINITION OF TERMS USED 1 The Problem 1 Scope of the problem 1 Limitations of the study . 2 Importance of the study 2 Definition of Terms . 3 Analysis, analytical 3 Sensational . 3 Synthetic, synthesis 3 II. SEARCH OF THE LITERATURE 4 III. PROCEDURE OF THE STUDY 6 IV. TREATMENT OF SELECTED WRITINGS AND ILLUSTRATIONS • 7 V. ANALYSIS AND FINDINGS OF THE STUDY 37 VI. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FURTHER STUDY 43 BIBLIOGRAPHY • 44 APPENDIX 46 CHAPTER I THE PROBLEM AND DEFINITION OF TERMS USED The writer assumes that Cubism has had a significant effect on American Art. -

Comparing and Contrasting Expressionism, Abstract, and Pop Art William Johnson

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Outstanding Honors Theses Honors College 5-2-2011 Comparing and Contrasting Expressionism, Abstract, and Pop Art William Johnson Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/honors_et Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Johnson, William, "Comparing and Contrasting Expressionism, Abstract, and Pop Art" (2011). Outstanding Honors Theses. Paper 86. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/honors_et/86 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Outstanding Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Johnson & Mostajabian 1 William Johnson and Kiana Mostajabian IDH 5975 Wallace Wilson March 29, 2011 From Mondrian to Warhol: Creating Abstract, Abstract Expressionism, and Pop Art Introduction: This is not your typical art history thesis. We have written this thesis to educate not only ourselves, but to give other non art and art history majors, an idea of where to start if you were thinking about exploring the subject. With little background in art and art history, we didn’t know where to start looking, but quickly found three art movements that interested us the most: Abstract, Abstract Expressionism, and Pop Art. With our topics in mind we decided to paint six paintings, two in each movement, and yet it seemed that the six paintings by themselves were not enough. We wanted to learn more. To supplement those six paintings we wrote this paper to give some background information on each movement and how we incorporated the styles of each movement into our paintings. -

Jackson Pollock Pdf, Epub, Ebook

JACKSON POLLOCK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mike Venezia | 32 pages | 25 Nov 1999 | Hachette Children's Group | 9780516422985 | English | London, United Kingdom Jackson Pollock PDF Book Donate Login Sign up Search for courses, skills, and videos. In Pollock began psychiatric treatment for alcoholism , and he suffered a nervous breakdown in , which caused him to be institutionalized for about four months. Pollock was expelled from two high schools during his formative years, the second one being Los Angeles Manual Arts School, where he was encouraged to pursue his interest in art. He had struggled on it for a while, and he decided to take that painting off the easel, place it on the floor, and then pour some paint on the surface to finish it. Landau also presents the forensic findings of Harvard University and presents possible explanations for the forensic inconsistencies that were found in three of the 24 paintings. Related Artists. Art historians, at the time, coined this kind of painting, action painting, because of this very idea that you could imagine quite viscerally the actions that went into the making of the painting. It was a piece puzzle that they promoted as "the world's most difficult puzzle". Overwhelmed with Pollock's needs, Krasner was also unable to work. Learnodo Newtonic. Archived from the original on March 12, Retrieved July 23, Recover your password. We strive for accuracy and fairness. Kenneth Noland - At the time Krasner was visiting friends in Europe and she abruptly returned on hearing the news from a friend. Stella, proud of her family's heritage as weavers, made and sold dresses as a teenager. -

Tachisme Is an Exhibition That Ruptures Any Clear Distinction Between Photography and Painting

Justine Varga Tachisme Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne 4 April – 9 May 2020 Tachisme is an exhibition that ruptures any clear distinction between photography and painting. The negatives from which these photographs derive were smeared and stained with pigment during their long exposures. When these negatives are then printed from at large-scale in the darkroom, the latent inscriptions are revealed to intermingle with the distinctive signature of the artist’s fingertips, a trace of touching that is generally forbidden in the production of photographs. Justine Varga has always seen her photography in these terms, as a drawing with light, or more literally as a light-sensitive substrate on which she makes marks or allows the world to leave its own marks. These photographs are therefore the making visible of an art practice that is at once physical and chemical, autobiographical and contingent, painterly and photographic. In doing so, Tachisme asks viewers to reflect on the activity of decipherment in relation to photographs, making this exhibition a critical rumination on inscription, meaning and knowledge. Biography Justine Varga is known for her luminous photographs, some made with a camera and some without (and some made with a combination of the two). Employing techniques that deserve comparison with the earliest nineteenth-century photographic experiments, Varga’s work has been described as an autobiographical witnessing of the world – a memoire, rather than merely an act of representation. Film registers performative gestures – is drawn upon, handled, scratched, spat on, weathered, or absorbs aspects of her everyday life. Exposed to light for long periods, the film is processed and then printed at large scale in the darkroom, itself a process of transformation.