Comparing and Contrasting Expressionism, Abstract, and Pop Art William Johnson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Restoring Subjectivity and Brazilian Identity: Lygia Clark's Therapeutic

Restoring Subjectivity and Brazilian Identity: Lygia Clark’s Therapeutic Practice A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Eleanor R. Harper June 2010 © 2010 Eleanor R. Harper. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Restoring Subjectivity and Brazilian Identity: Lygia Clark’s Therapeutic Practice by ELEANOR R. HARPER has been approved for the School of Art and the College of Fine Arts by Jaleh Mansoor Assistant Professor of Art History Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT HARPER, ELEANOR R., M.A., June 2010, Art History Restoring Subjectivity and Brazilian Identity: Lygia Clark’s Therapeutic Practice (125 pp.) Director of Thesis: Jaleh Mansoor This thesis examines the oeuvre of Brazilian artist Lygia Clark (1920-1988) with respect to her progressive interest in and inclusion of the viewing subject within the work of art. Responding to the legacy of Portuguese occupation in her home of Brazil, Clark sought out an art that embraced the viewing subject and contributed to their sense of subjectivity. Challenging traditional models of perception, participation, and objecthood, Clark created objects that exceeded the bounds of the autonomous transcendental picture plane. By fracturing the surfaces of her paintings, creating objects that possess an interior and exterior, and by requiring her participants to physically manipulate her work, Clark demonstrated an alternative model of the art object and experience. These experiments took her into the realm of therapy under the influence of psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott’s work. -

DISPLACED BOUNDARIES: GEOMETRIC ABSTRACTION from PICTURES to OBJECTS Monica Amor

REVIEW ARTICLE Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/artm/article-pdf/3/2/101/720214/artm_r_00083.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 DISPLACED BOUNDARIES: GEOMETRIC ABSTRACTION FROM PICTURES TO OBJECTS monica amor suárez, osbel. cold america: geometric abstraction in latin america (1934–1973). exhibition presented by the Fundación Juan march, madrid, Feb 11–may 15, 2011. crispiani, alejandro. Objetos para transformar el mundo: Trayectorias del arte concreto-invención, Argentina y Chile, 1940–1970 [Objects to Transform the World: Trajectories of Concrete-Invention Art, Argentina and Chile, 1940–1970]. buenos aires: universidad nacional de Quilmes, 2011. The literature on what is generally called Latin American Geometric Abstraction has grown so rapidly in the past few years, there is no doubt that the moment calls for some refl ection. The fi eld has been enriched by publications devoted to Geometric Abstraction in Uruguay (mainly on Joaquín Torres García and his School of the South), Argentina (Concrete Invention Association of Art and Madí), Brazil (Concretism and Neoconcretism), and Venezuela (Geometric Abstraction and Kinetic Art). The bulk of the writing on these movements, and on a cadre of well-established artists, has been published in exhibition catalogs and not in academic monographs, marking the coincidence of this trend with the consolidation of major private collections and the steady increase in auction house prices. Indeed, exhibitions of what we can broadly term Latin American © 2014 ARTMargins and the Massachusetts Institute -

Barnett Newman's

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Art and Art History Faculty Research Art and Art History Department 2013 Barnett ewN man's “Sense of Space”: A Noncontextualist Account of Its Perception and Meaning Michael Schreyach Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/art_faculty Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Repository Citation Schreyach, M. (2013). Barnett eN wman's “Sense of Space”: A Noncontextualist Account of Its Perception and Meaning. Common Knowledge, 19(2), 351-379. doi:10.1215/0961754X-2073367 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art and Art History Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art and Art History Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES BARNETT NEWMAN’S “SENSE OF SPACE” A Noncontextualist Account of Its Perception and Meaning Michael Schreyach Dorothy Seckler: How would you define your sense of space? Barnett Newman: . Is space where the orifices are in the faces of people talking to each other, or is it not [also] between the glance of their eyes as they respond to each other? Anyone standing in front of my paint- ings must feel the vertical domelike vaults encompass him [in order] to awaken an awareness of his being alive in the sensation of complete space. This is the opposite of creating an environment. This is the only real sensation of space.1 Some of the titles that Barnett Newman gave to his paintings are deceptively sim- ple: Here and Now, Right Here, Not There — Here. -

Patel Spring 2017 GL ARH 4470 Syllabus

Do not copy without the express written consent of the instructor. Syllabus Spring 2017 ARH 4470/ARH 5482 Contemporary Art A Discipline-Specific Global Learning Course1 Tuesday and Thursday 2-3:15pm Green Library, Room 165 Instructor: Dr. Alpesh Kantilal Patel Assistant Professor, Contemporary Art and Theory Director, MFA in Visual Arts Affiliate Faculty, Center for Women’s and Gender Studies Affiliate Faculty, African and African diaspora Program Contact information for instructor: Department of Art + Art History MM Campus, VH 235 Preferred mode of contact: [email protected] Office hours: Thursday: 12:45-1:45pm Course description: This course examines major artists, artworks, and movements after World War II; as well as broader visual culture—everything from music videos and print advertisements to propaganda and photojournalism—especially as the difference between ‘art’ and non-art increasingly becomes blurred and the objectivity of aesthetics is called into question. Movements studied include Abstract Expressionism, Pop, and Minimalism in the 1950s and 1960s; Post-Minimalism/Process Art, and Land art in the late 1960s and 1970s; Pastiche/Appropriation and rise of interest in “identity” in the 1980s; and the emergence of Post-Identity, Relational Art, Internet/New Media art, and Post- Internet art in the 1990s/post-2000 period. This course will explore the expansion of the art world beyond “Euro- America.” In particular, we will consider the shift from an emphasis on the international to transnational. We will focus not only on artistic production in the US, but also that in Europe, South and East Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. -

Teaching Strategies: How to Explain the History and Themes of Abstract Expressionism to High School Students Using the Integrative Model

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Honors Theses Undergraduate Research 2014 Teaching Strategies: How to Explain the History and Themes of Abstract Expressionism to High School Students Using the Integrative Model Kirk Maynard Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/honors Part of the Art and Design Commons Recommended Citation Maynard, Kirk, "Teaching Strategies: How to Explain the History and Themes of Abstract Expressionism to High School Students Using the Integrative Model" (2014). Honors Theses. 92. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/honors/92 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. 2014 Kirk Maynard HONS 497 [TEACHING STRATEGIES: HOW TO EXPLAIN THE HISTORY AND THEMES OF ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM TO HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS USING THE INTEGRATIVE MODEL] Abstract: The purpose of my thesis is to create a guideline for teachers to explain art history to students in an efficient way without many blueprints and precedence to guide them. I have chosen to focus my topic on Abstract Expressionism and the model that I will be using to present the concept of Abstract Expressionism will be the integrated model instructional strategy. -

Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU 18th Annual Africana Studies Student Research Africana Studies Student Research Conference Conference and Luncheon Feb 12th, 1:30 PM - 2:45 PM Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art Shelby Miller Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons Miller, Shelby, "Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art" (2017). Africana Studies Student Research Conference. 1. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf/2016/004/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Events at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Africana Studies Student Research Conference by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Shelby Miller Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art Bibliographic Style: MLA 1 How does one define the concepts of space and place and further translate those theories to the Caribbean region? Through abstract modes of representation, artists from these islands can shed light on these concepts in their work. Involute theories can be discussed in order to illuminate the larger Caribbean space and all of its components in abstract art. The trialectics of space theory deals with three important factors that include the physical, cognitive, and experienced space. All three of these aspects can be displayed in abstract artwork from this region. By analyzing this theory, one can understand why Caribbean artists reverted to the abstract style—as a means of resisting the cultural establishments of the West. To begin, it is important to differentiate the concepts of space and place from the other. -

American Abstract Expressionism

American Abstract Expressionism Cross-Curricular – Art and Social Studies Grades 7–12 Lesson plan and artwork by Edwin Leary, Art Consultant, Florida Description Directions This project deals with the infusion between Art History Teacher preparation: and Art Making through American Abstract Expressionism. Gather examples of artists that dominated this movement, American Abstract Expressionism is truly a U.S. movement that display them in the Art Room with questions of: Who uses emphasizes the act of painting, inherent in the color, texture, organic forms? Dripped and splashed work? Why the highly action, style and the interaction of the artist. It may have been colored work of Kandinsky? Why the figurative aspects of inspired by Hans Hofmann, Arshile Gorky and further developed DeKooning? by the convergence of such artists as Jackson Pollack, William With the students: DeKooning, Franz Kline, Mark Rothko and Wassily Kandinsky. 1 Discuss the emotions, color and structure of the displayed Objectives artists’ work. Discuss why American Abstract Expressionism is less about • Students can interactively apply an art movement to an art 2 process-painting. style than attitude. • This art-infused activity strengthens their observation and 3 Discuss why these artists have such an attachment of self awareness of a specific artist’s expression. expression as found in their paintings yet not necessarily found in more academic work? Lesson Plan Extensions 4 Gather the materials and explain why the vivid colors of Apply this same concept of investigation, application and art Fluorescent Acrylics were used, and what they do within a making to other movements or schools of art. -

The Russian Avant-Garde 1912-1930" Has Been Directedby Magdalenadabrowski, Curatorial Assistant in the Departmentof Drawings

Trustees of The Museum of Modern Art leV'' ST,?' T Chairm<ln ,he Boord;Ga,dner Cowles ViceChairman;David Rockefeller,Vice Chairman;Mrs. John D, Rockefeller3rd, President;Mrs. Bliss 'Ce!e,Slder";''i ITTT V P NealJ Farrel1Tfeasure Mrs. DouglasAuchincloss, Edward $''""'S-'ev C Burdl Tn ! u o J M ArmandP Bar,osGordonBunshaft Shi,| C. Burden,William A. M. Burden,Thomas S. Carroll,Frank T. Cary,Ivan Chermayeff, ai WniinT S S '* Gianlui Gabeltl,Paul Gottlieb, George Heard Hdmilton, Wal.aceK. Harrison, Mrs.Walter Hochschild,» Mrs. John R. Jakobson PhilipJohnson mM'S FrankY Larkin,Ronalds. Lauder,John L. Loeb,Ranald H. Macdanald,*Dondd B. Marron,Mrs. G. MaccullochMiller/ J. Irwin Miller/ S.I. Newhouse,Jr., RichardE Oldenburg,John ParkinsonIII, PeterG. Peterson,Gifford Phillips, Nelson A. Rockefeller* Mrs.Albrecht Saalfield, Mrs. Wolfgang Schoenborn/ MartinE. Segal,Mrs Bertram Smith,James Thrall Soby/ Mrs.Alfred R. Stern,Mrs. Donald B. Straus,Walter N um'dWard'9'* WhlTlWheeler/ Johni hTO Hay Whitney*u M M Warbur Mrs CliftonR. Wharton,Jr., Monroe * HonoraryTrustee Ex Officio 0'0'he "ri$°n' Ctty ot^New^or^ °' ' ^ °' "** H< J Goldin Comptrollerat the Copyright© 1978 by TheMuseum of ModernArt All rightsreserved ISBN0-87070-545-8 TheMuseum of ModernArt 11West 53 Street,New York, N.Y 10019 Printedin the UnitedStates of America Foreword Asa resultof the pioneeringinterest of its first Director,Alfred H. Barr,Jr., TheMuseum of ModernArt acquireda substantialand uniquecollection of paintings,sculpture, drawings,and printsthat illustratecrucial points in the Russianartistic evolution during the secondand third decadesof this century.These holdings have been considerably augmentedduring the pastfew years,most recently by TheLauder Foundation's gift of two watercolorsby VladimirTatlin, the only examplesof his work held in a public collectionin the West. -

Chapter 12. the Avant-Garde in the Late 20Th Century 1

Chapter 12. The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century 1 The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century: Modernism becomes Postmodernism A college student walks across campus in 1960. She has just left her room in the sorority house and is on her way to the art building. She is dressed for class, in carefully coordinated clothes that were all purchased from the same company: a crisp white shirt embroidered with her initials, a cardigan sweater in Kelly green wool, and a pleated skirt, also Kelly green, that reaches right to her knees. On her feet, she wears brown loafers and white socks. She carries a neatly packed bag, filled with freshly washed clothes: pants and a big work shirt for her painting class this morning; and shorts, a T-shirt and tennis shoes for her gym class later in the day. She’s walking rather rapidly, because she’s dying for a cigarette and knows that proper sorority girls don’t ever smoke unless they have a roof over their heads. She can’t wait to get into her painting class and light up. Following all the rules of the sorority is sometimes a drag, but it’s a lot better than living in the dormitory, where girls have ten o’clock curfews on weekdays and have to be in by midnight on weekends. (Of course, the guys don’t have curfews, but that’s just the way it is.) Anyway, it’s well known that most of the girls in her sorority marry well, and she can’t imagine anything she’d rather do after college. -

Staging Revolution: the Constructivist Debate About Composition

Staging Revolution: The Constructivist Debate about Composition Introduction Among the relatively few areas of agreement after the 1917 Russian Revolution, two are particularly noteworthy. The first is the widespread perception that the urban environment was chaotic. Whereas few people agreed as to the source of this chaos (choosing to blame it on the capitalists, the architects, or the intelligentsia), almost everyone believed that urban life after the revolution did not justify the sacrifices and traumas imposed by three years of civil war. The second area of agreement concerned the role of the theater: despite continued and almost irreconcilable differences about what the future should look like, there was almost complete agreement that art and theater could be “weapons” or tools in the revolution. Theater, in particular, would lead the way: from Lenin’s project for monumental propaganda (1918) to the Russian futurists’ declaration that the “streets should be a holiday of art for the people,” there was widespread agreement that art should be taken to the streets, that it was capable of communicating messages in a voice which would be understood, and that theatricality was the key to the unification of the arts. Ironically, one of the reasons why constructivism has been so difficult to study is the fact that it was long understood as a form of art which was against the creation of art. But one of the core values of constructivism was not the rejection of art but the belief that the only type of art which has meaning is one which challenges boundaries and definitions, and that part of this challenge concerns the relationship between the audience and the art work, whether we talk about theater, cinema, photography, or objects. -

Art in 1960S

Abstract Expressionism 1940s-1960s A form of abstract art that emphasized spontaneous, intuitive creation of unstructured expressions of the artist’s unconscious Action Painting: emphasized the dynamic handling of paint and techniques that were partly dictated by chance. The act of painting was as significant as the finished work: Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning Jackson Pollock, Blue Poles, 1952 William de Kooning, Untitled, 1975 Color-Field Painting: used large, soft-edged fields of flat color: Mark Rothko, Ab Reinhardt Mark Rothko, Lot 24, “No. 15,” 1952 “A square (neutral, shapeless) canvas, five feet wide, five feet high…a pure, abstract, non- objective, timeless, spaceless, changeless, relationless, disinterested painting -- an object that is self conscious (no unconsciousness), ideal, transcendent, aware of no thing but art (absolutely no anti-art). Ad Reinhardt, Abstract Painting,1963 –Ad Reinhardt Minimalism 1960s rejected emotion of action painters sought escape from subjective experience downplayed spiritual or psychological aspects of art focused on materiality of art object used reductive forms and hard edges to limit interpretation tried to create neutral art-as-art Frank Stella rejected any meaning apart from the surface of the painting, what he called the “reality effect.” Frank Stella, Sunset Beach, Sketch, 1967 Frank Stella, Marrakech, 1964 “What you see is what you see” -- Frank Stella Postminimalism Some artists who extended or reacted against minimalism: used “poor” materials such felt or latex emphasized process and concept rather than product relied on chance created art that seemed formless used gravity to shape art created works that invaded surroundings Robert Morris, Felt, 1967 Richard Serra, Cutting Device: Base Plat Measure, 1969 Hang Up (1966) “It was the first time my idea of absurdity or extreme feeling came through. -

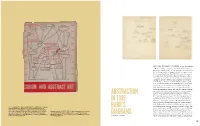

Abstraction in 1936: Barr's Diagrams

ALMOST SINCE THE MOMENT OF ITS FOUNDING, in 1929, The Museum of Modern Art has been committed to the idea that abstraction was an inherent and crucial part of the development of modern art. In fact the 1936 exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art, organized by the Museum’s founding director, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., made this argument its central thesis. In an attempt to map how abstraction came to be so important in modern art, Barr created a now famous diagram charting the history of Cubism’s and abstraction’s development from the 1890s to the 1930s, from the influence of Japanese prints to the aftermath of Cubism and Constructivism. Barr’s chart, which was published on the dust jacket of the exhibition’s catalogue (plate 452), began in an early version as a simple outline of the key factors affecting early modern art, and of the development of Cubism in particular, but over successive iterations became increasingly complex in its overlapping and intersecting lines of influence ABSTRACTION 1 (plates 453–58). The chart has two principal axes: on the vertical, time, and on the horizontal, styles or movements, with both lead- ing inexorably to the creation of abstract art. Key non-Western IN 1936: influences, such as “Japanese Prints,” “Near-Eastern Art,” and “Negro Sculpture,” are indicated by a red box. “Machine Esthetic” is also highlighted by a red box, and “Modern Architecture,” by 452. The catalogue for Cubism and Abstract Art, an exhibition at the Museum BARR’S which Barr meant the International Style, by a black box.