1966- Reports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Operator Profile 2002 - 2003

BUS OPERATOR PROFILE 2002 - 2003 Operator .Insp 02-03 .OOS 02-03 OOS Rate 02-03 OpID City Region 112 LIMOUSINE INC. 2 0 0.0 28900 CENTER MORICHES 10 1ST. CHOICE AMBULETTE SERVICE LCC 1 0 0.0 29994 HICKSVILLE 10 2000 ADVENTURES & TOURS INC 5 2 40.0 26685 BROOKLYN 11 217 TRANSPORTATION INC 5 1 20.0 24555 STATEN ISLAND 11 21ST AVE. TRANSPORTATION 201 30 14.9 03531 BROOKLYN 11 3RD AVENUE TRANSIT 57 4 7.0 06043 BROOKLYN 11 A & A ROYAL BUS COACH CORP. 1 1 100.0 30552 MAMARONECK 08 A & A SERVICE 17 3 17.6 05758 MT. VERNON 08 A & B VAN SERVICE 4 1 25.0 03479 STATEN ISLAND 11 A & B'S DIAL A VAN INC. 23 1 4.3 03339 ROCKAWAY BEACH 11 A & E MEDICAL TRANSPORT INC 60 16 26.7 06165 CANANDAIGUA 04 A & E MEDICAL TRANSPORT INC. 139 29 20.9 05943 POUGHKEEPSIE 08 A & E TRANSPORT 4 0 0.0 05508 WATERTOWN 03 A & E TRANSPORT SERVICES 39 1 2.6 06692 OSWEGO 03 A & E TRANSPORT SERVICES INC 154 25 16.2 24376 ROCHESTER 04 A & E TRANSPORT SERVICES INC. 191 35 18.3 02303 OSWEGO 03 A 1 AMBULETTE INC 9 0 0.0 20066 BROOKLYN 11 A 1 LUXURY TRANSPORTATION INC. 4 2 50.0 02117 BINGHAMTON 02 A CHILDCARE OF ROOSEVELT INC. 5 1 20.0 03533 ROOSEVELT 10 A CHILD'S GARDEN DAY CARE 1 0 0.0 04307 ROCHESTER 04 A CHILDS PLACE 12 7 58.3 03454 CORONA 11 A J TRANSPORTATION 2 1 50.0 04500 NEW YORK 11 A MEDICAL ESCORT AND TAXI 2 2 100.0 28844 FULTON 03 A&J TROUS INC. -

The Fare Box

,,,IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII111111III11111III .11111111 THE.I .1111.l FARE1 IIIIIIIIIIIII I BOXI 111111111111 .1 .11 .1 .1 . .1 .1111111111,,,11,1 A monthly News-hotter for Transportation Token Collectors 11111111111111111111111 . 111111.I. .IIII 111111 .11111111 II . .IIIIII .. .. .i111111111111IIIIIII. ..1 al .i all1111111111111111111111111111111 . .. .. .. .. .. .. .... .. .. ..... .. .... ..... .. .. .. ... NEW ISSUES EDITOR EDITOR $flH'HI NI11raliHiIt J JR; 634 ~Ashbury Street . jiL COFFEE, P. g. 4ox 1204 ,San Francisco, ~california 94117 (4oston, 14assachusetts 02104 Now Issues Service Parking Tokens jOI-I]V t. NICOLO$I$ DWINU I;. RFII$kfie 3002 ;Galindo Street P. 0. Box 1302 Oakland, (California 94601 Los Altos, California 94022 Volume 33, Plumber 1 JANUARY, 1979 Our379thIssue WALTER J. STUCKE and CLARENCE E . ZIEGLER We begin another year with an unhappy note . Walter J. Stucke, AVA #1616, of Chicago, joined us in 1976 . He was already retired at that time . I did not know him well, but his brief tenure with us resulted in some interesting correspondence, and I shall miss him, as will all of the Chicago members . He died last October at age 64 . Clarence Ziegler, AVA #1598, of' Port Huron, Michigan, also joined in 1976 . Clarence was a very active collector of all manner of tokens, and his frequent full page auc- tions in TANS JOURNAL are familiar to most of us . Ibny are the phone conversations I had with him, and more the letters I received from him . 1- could always count on re- ports of real estate tokens, taxicab charge coins, as well as other types of tokens in which I had an interest . His was a vital presence and a dear friendship . -

MTA New York City Subway� S N

WESTCHESTER THE BRONX R 2 k I a V r Wakefield t E PELHAM R Wakefield Wakefield–241 St m D Woodlawn Norwood–205 St Pelham Bay Park A BAY Van Cortlandt Pk–242A St 241 St Subway 2 L E Subway 4 PARK Subway D 2 Subway 6 Subway 19 A EASTCHESTER V B 5 NYC Transit Bus R P O NYC Transit Bus Y O NYC Transit Bus Nereid Av CIT NYC Transit Bus NYC Transit Bus A T Eastchester Bx41OP Webster Av/White Plains Rd R D fi - T Bx16 E 233 St/Nereid Av (238 St) 3 S CO W Bx10 Riverdale 23 Dyre Av Bx5 Bruckner Blvd/Story Av W Bx9 Broadway/West Farms Sq A A Y Bx34 Bainbridge Av 2•5 Bee-Line N W 254 ST Bx16 E 233 St/Nereid Av Bx12 Pelham Pkwy/Bay Plaza S Riverdale 5 H 40 Westchester County Med Ctr I Bee-Line Bx28 E Gun Hill Rd Woodlawn 233 St Bx12 Orchard Beach N Bee-Line G T 1 Yonkers/Hastings • Baychester 41 WestchesterV County Med Ctr 4 Yonkers Bx30 Boston Rd/E Gun Hill Rd 2 5 A Bx14 Country Club–Parkchester O N Av W 1C Westchester Cty Comm Coll 42 New Rochelle 20 White Plains Bx34 Bainbridge Av 225 ST CO-OP O Bx29 Bay Plaza–City Island B 5 T L R V 1T Tarrytown M 225 St 222 ST CITY A 21 White Plains Metro-North D 1 O h B t Queens Surface L S r • 1W White Plains A 2 5 D H o C R N QBx1 Co-op City–Flushing O 2 Yonkers 9 - O ORCHARD L 4 N o d N r U O t I BEACH T 219 St A Van Cortlandt Park e BAYCHESTER 3 White Plains Bee-Line MTA New York City Subway S n M A 242 St 2•5 O THE VAN Woodlawn V 45 Eastchester B V u Y A 1•9 CORTLANDT 4 Y P Marble Hill–225 St I A E N PARK K K Gun Hill Rd W W o RIVERDALE D Gun Hill Rd R V W P SO Williams U K E D BRONX A K B Subway 19 A R -

November 2002 Bulletin.Pub

TheNEW YORK DIVISION BULLETIN - NOVEMBER, 2002 Bulletin New York Division, Electric Railroaders’ Association Vol. 45, No. 11 November, 2002 The Bulletin NEW MIDTOWN DIRECT SERVICE FROM Published by the MONTCLAIR HEIGHTS New York Division, Electric Railroaders’ by Randy Glucksman Association, Incorporated, PO As it turned out, the last inbound and out- side at Benson Street, photographing the six- Box 3001, New York, bound runs on the Boonton (actually Green- car train of Comet Is, which by the way, was New York 10008- wood Lake Branch) were so low-key that filthy with litter. Only one car, former Snack- 3001. they could be classified as “no-key.” Steve Bar car 1603, was being used. Lofthouse and I drove to the Montclair A colorful brochure titled Introducing Mid- Editorial Staff: Heights station in plenty of time to ride Train town Direct Montclair – The Montclair- #1036 (7:27 PM), which should have been Boonton Connection was issued. Besides Editor-in-Chief: the “last” inbound train. An email that circu- describing the new service, it contains de- Bernard Linder lated the previous day mentioned that this tailed maps showing the streets and high- News Editor: train would be the second train to operate ways that serve each station. There are Randy Glucksman over the new connection. What we learned maps for what is called the Eastern Essex after arriving there was that after the depar- Region, Montclair Region, Southern Passaic/ Production ture of Train #1074, that the final two trains of Eastern Morris Region, Northern Morris Re- Manager: the day, #1032 and 1036, were replaced by gion, and Northwest Region, plus a map of David Ross Decamp buses. -

New York City Department of Transportation

NEW YORK CITY DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION Passenger Transport Division Battery Maritime Bldg, Third Floor New York, NY 10004 (212) 487-8300 Web Site: http://www.ci.nyc.ny.us/html/dot/home.html State Legislative Districts: Senate: 7, 9 - 23, 25 - 34 Assembly: 16, 17, 20 - 58, 62 - 83 The New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT) sponsors seven private transit operators within New York City including: Command Bus, Green Bus Lines, Jamaica Buses, Queens Surface, Triboro Coach, Liberty Lines Express, and New York Bus Tours. NYCDOT also contracts with Atlantic Express to provide two express routes for commuters from the South Shore of Staten Island. The NYCDOT bus system is comprised of 1,300 buses, the 9th largest fleet and the largest privately operated fleet in the nation and more than 1/4 the size of the MTA NYC Transit bus fleet. that involved three companies: Queens Surface, Five of seven original operators provide local and Jamaica Buses and Triboro Coach. The first strike express service, while two provide exclusively express lasted only two days, February 28 and 29. However, service. Together, there are 35 express and 47 local the second strike was more prolonged, lasting five and routes. Liberty Lines and New York Bus Tours provide a half weeks, from June 29 to August 6. Each day of express services from the Bronx to Manhattan. Green the strike led to the loss of approximately 193,000 Bus Lines, Jamaica Buses, Queens Surface and Triboro riders. In the aftermath of the strike there was a Coach provide local service in Queens and express residual impact period before ridership returned to service from Queens to Manhattan. -

Downtown Jamaica: Gateway to the New York Region Design, Market and Mobility Assessments

Downtown Jamaica: Gateway to the New York Region Design, Market and Mobility Assessments December 2016 Acknowledgments This report was commissioned by the Greater Jamaica Development Corporation. Regional Plan Association Greater Jamaica Development Corporation Pierina Ana Sanchez, New York Director Hope Knight, President Robert Lane, Senior Fellow for Urban Design Justin Rodgers, Managing Director, Real Estate Development Jeffrey Zupan, Peter W. Herman Chair for Transportation and Urban Planning Christopher Jones, Senior Vice President and Chief Planner Jim Diego, Senior Project Manager, Real Estate Development Richard Barone, Vice President for Transportation and Urban Planning Vanessa Barrios, Associate Planner, Outreach Benjamin Oldenburg, Senior Graphic Designer Special thanks to the following for their contributions: Technical Advisory Committee** Jamaica NOW Leadership Council Patty Clark, Senior Advisor of Aviation Policy, PANYNJ Adrienne Adams, Chairperson, Queens Community Board 2 Frank DiMola, Executive Director, Terminal 4 Airline Consor- Rhonda Binda, Downtown Jamaica BID tium, JFK Airport (GJDC Board) Brian Browne, St. Johns University Ian Harris, Co-Chair, Jamaica NOW Leadership Council Nick Buron, Queens Library Central Branch Marcia Keizs, President, York College Ricardi Calixte, Queens Economic Development Corporation Peter Kulka, President, KJL Property Management Corporation Tonya Cantlo-Cockfield, Jamaica Center for Arts & Learning (GJDC Board) Clive Dawkins, Property Owner Meredith Marshall, Managing Partner & Co-Founder, BRP Kevin J. Forrestal, Community Board 8 Member Corporation Deepmalya Ghosh, Chider Center of NY Melva Miller, Deputy Borough President, Office of the Queens Glenn Greenidge, Sutphin BID Borough President Michael Griffith, NYC Department of Transportation Jeffrey Moerdler, Partner, Mintz, Levin, Cohn, Ferris, Glovsky, Tyrell Hankerson, Resident and Popeo, P.C. (RPA NY Committee) Ian Harris*, Community Board 12 Member, Resident Elisa Picca, Executive Vice President, LIRR Howard Hecht, Community Leader Elliot G. -

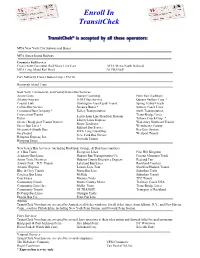

List of Transitchek Operators

Enroll In TransitChek MTA New York City Subway and Buses MTA Staten Island Railway Commuter Rail Services Connecticut Commuter Rail/Shore Line East MTA Metro-North Railroad MTA Long Island Rail Road NJ TRANSIT Port Authority Trans-Hudson Corp. (PATH) Roosevelt Island Tram New York, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania Bus Services Arrow Lines Harran Coachway Peter Pan Trailways Atlantic Express HART Bus Service Queens Surface Corp. * Coastal Link Huntington Area Rapid Transit Spring Valley Coach Collins Bus Service Jamaica Buses * Sunrise Coach Lines Command Bus Company * Kelley Transportation Swift Transportation Connecticut Transit Leprechaun Line/Hendrick Hudson Trans-Bridge Lines Datco Triboro Coach Corp. * Liberty Lines Express Greater Bridgeport Transit District Martz Trailways Waterbury Northeast Transit Green Bus Lines * Westchester County— Milford Bus Service Greenwich Shuttle Bus MTA Long Island Bus Bee-Line System Greyhound New York Bus Service Westport Transit Hampton Express, Inc. Norwalk Transit Hampton Jitney New Jersey Bus Services (including Rockland, Orange, & Dutchess counties) A-1 Bus Tours Evergreen Lines Pine Hill-Kingston Academy Bus Lines Hudson Bus Transportation Co. Pocono Mountain Trails Anton Travel Services Hudson County Executive Express Red and Tan Asbury Park—N.Y. Transit Lakeland Bus Lines Rockland Coaches Atlantic Express Leisure Line Tour Shortline/Hudson Transit Blue & Grey Transit Martz Bus Line Suburban Trails Carefree Bus Lines McRide Suburban Transit Coachways Monsey Trails TPC Transit Community Coach Morris County Metro Trailway Coach USA Community Lines Inc. Muller Tours Trans-Bridge Lines Community Transit NJ TRANSIT Transport of Rockland DeCamp Bus Lines Olympia Trails Drogin Bus Co. Peter Pan Line Amtrak TransitChek Vouchers are accepted by Amtrak at all ticket windows, for all ticket types, from Albany, N.Y., and New Haven, Conn., south to Philadelphia, including New York Penn Station, and Newark Penn Station. -

View/Download Entire Chapter

CHAPTER III STATUS AND PERFORMANCE OF MAJOR TRANSIT SYSTEMS The New York State Department of Transportation is groupings. It will also provide an overview of trends in required by Section 18-b of Transportation Law to report “Effectiveness,” “Efficiency” and “Economy” statistical on the efficiency, effectiveness and economy of transit measures comprised of the following ratios: service. This Chapter addresses this requirement by presenting an overview of trends in the performance of C “Effectiveness” is measured by the revenue the State’s transit systems. passenger to revenue vehicle mile ratio; The Chapter is divided into two sections. C “Efficiency” is measured by the operating cost per revenue vehicle mile ratio; • A Statewide overview of the performance of transit systems, grouped by service type and C “Economy” is measured by the operating common market characteristics. revenue to operating cost ratio. • A detailed reporting on the status and Effectiveness, efficiency and economy performance performance of specific transit systems that measure figures in this report include data for all report financial and operating statistics to the sponsored operators that reported 17-a statistics for Department of Transportation under the 2001. Prior to the 2001 edition, tables have included requirements of Section 17-a of State financial and operational data for the largest systems Transportation Law. within the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) Commuter District. Thus the more comprehensive five In 2001, the Department of Transportation, Passenger year statistics in this report will not in every case match Transportation Division engaged in an extensive effort to those found in previous Transit Annual Reports. Non- improve the quality, consistency and management of the urbanized and small city systems are not required to data it collects under both the 17a and STOA formula submit 17-a statistics. -

A Directory of Regularly Scheduled, Fixed Route, Local Public

A DIRECTORY OF REGULARLY SCHEDULED, FIXED ROUTE, LOCAL PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION SERVICE IN URBANIZED AREAS OVER 50,000 POPULATION AUGUST 1981 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION Urban Mass Transportation Administration Office of Planning, Management and Demonstrations Washington, D.C. 20590 . FOR RELEASE MONDAY UMTA Technical Notice 2-81 August 10, 1981 The U. S. DeDartment of Transportation's Urban Mass Transportation Administration released today an updated directory of 686 local fixed route transit operations in 279 urbanized areas (UZAs) of over 50,000 population. As shown in the summaries on page 19, the vehicle requirements for weekday schedules in these UZAs are 3,566 commuter rail cars, 7,450 rapid transit cars, 551 light rail cars, 42,925 motor coaches, 503 trolley coaches and 28 cable cars. These figures are peak requirements, not fleet size. For purposes of this compilation, a transit operation is a fixed route, regularly scheduled service, available to the general public, offering rides wholly within, or commuter rides from outside a particular UZA. Maps showing UZA borders appear in U.S. Census Bureau publication PC (1)-A, by states. UZA listings are in the order of population rank. To find a particular UZA, refer to page 1, where UZAs are listed alphabetically, or to page 21, where they are listed by states. Users of this directory desiring to identify systems of a certain size, or operating different modes, will find useful information in column 5. This directory replaces Technical Notice 2-80 dated August 1, 1 980. Another listing in this series is TN 1-81 dated March 9, 1981, reporting services available in communities of less than 50 ,000 population. -

Travel Survey Manual Appendices

Travel Survey Manual Appendices Travel Model Improvement Program Travel Survey Manual - A~~endices June 1996 Prepared by Cambridge Systematic, Inc. Prepared for U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Transit Administration Federal Highway Administration Office of the Secretary U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Appendix A The Costs of Travel Surveys The Costs of Travel Surveys Travel surveyors are almost always constrained by limited available resources. More often than not, the survey design and sampling tasks are bounded by funding limits, so the survey team needs to be able to esti- mate the cost of various types of surveys early in their effort. Estimating Costs Based on Previous Survey Efforts The most common source of rough cost estimates is the reported costs of previous efforts. The costs of travel survey efforts are often reported in technical papers and reports. In addition, rules-of-thumb about survey costs are commonly cited. For instance, many surveyors use a figure of $100 per completed survey for telephone-mail-telephone household travel surveys. Unfortunately, there are several problems with relying on past survey experience in estimating costs: ● The analyses rarely account for inflation; ● The analyses do not account for deteriorating cooperation rates over time; ● The analyses do not account for geographic differences; ● It is often difficult to determine which survey cost elements are included in the past cost estimates; and ● It is highly unlikely that the past efforts will include the same survey design=le-ments and sampling considerations as the survey team’s pro- posed effort. To analyze the cost of a past survey effort, the survey team needs to account for inflation. -

State of Transportation Statistics

Transportation Statistics Annual Report December 2006 Bureau of Transportation Statistics Research and Innovative Technology Administration U.S. Department of Transportation To obtain Transportation Statistics Annual Report and other BTS publications Mail: Product Orders Bureau of Transportation Statistics Research and Innovative Technology Administration U.S. Department of Transportation 400 Seventh Street, SW, Room 4117 Washington, DC 20590 Phone: 202-366-DATA Internet: www.bts.dot.gov BTS Information Service E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 800-853-1351 Recommended citation U.S. Department of Transportation, Research and Innovative Technology Administration, Bureau of Transportation Statistics, Transportation Statistics Annual Report (Washington, DC: 2006) All material contained in this report is in the public domain and may be used and reprinted without special permission; citation as to source is required. Acknowledgments U.S. Department of Produced under the Transportation direction of: Wendell Fletcher Mary E. Peters Assistant Director for Secretary Transportation Analysis Thomas J. Barrett Project Manager Deputy Secretary (Acting) Jennifer Brady Major Contributors Felix Ammah-Tagoe Janice Lent Steve Beningo Getachew Mekonnen Research and David Chesser Jeffery Memmott Innovative Technology Scott Dennis Long Nguyen Administration Bruce Goldberg Ken Notis Xiaoli Han Michael Sprung John Bobo Maha Khan Jie Zhang Administrator (Acting) Other Contributors Bill Bannister Jonaki Bose Carol Brandt Bureau of Don Bright Transportation Lee Giesbrecht Statistics Alan Jeeves Marline Reese Steven D. Dillingham Director Editor William H. Moore Report Layout, Production, and Cover Design Alpha Glass Wingfi eld Preface ongress requires the Bureau of Transportation Statistics (BTS) of Cthe Research and Innovative Technology Administration to report on transportation statistics to the President and Congress. -

Mta Bus Company Report

MTA/OIG Report #2008-7 October 2008 MTA BUS COMPANY REPORT Barry L. Kluger MTA Inspector General State of New York INTRODUCTION In June 2007, the President of MTA Bus and the MTA Auditor General requested that the Office of the MTA Inspector General (OIG) assist them in reviewing certain aspects of MTA Bus operations. Those requests were prompted by MTA Audit Services’ (Audit Services) identification of overall control weaknesses, unusual transactions, and many management personnel vacancies creating potential fraud vulnerabilities. The general areas we focused on were payroll, overtime, accounts payable, inventory and procurement. This report will discuss our investigative and audit efforts, and provide details with respect to specific findings and recommendations. OIG conducted numerous tests to determine whether various control weakness cited by Audit Services were exploited to an extent that evidence of criminality might be found. As can be seen from the Miscellaneous Issues section, the majority of our tests revealed only minor problems. Some of the tests we performed in the areas of payroll, procurement/inventory and accounts payable did cause us to make certain recommendations for improvement. However, no evidence of criminality was found. The following is a summary of those findings. • Payroll – MTA Audit Services found, and this Office verified, that employees at the College Point Maintenance Shop were not complying with a management directive that they electronically swipe in and out each day. MTA Bus management responded by issuing a memo directing that all employees were required to swipe and that employees would lose pay for failing to comply. Our study revealed that MTA Bus management at the College Point Depot never issued clear directives to the employee assigned to administer the program, and never verified that the sanctions were being imposed.