Soil Crusts of Moses Coulee Area Washington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washington Division of Geology and Earth Resources Open File Report

RECONNAISSANCE SURFICIAL GEOLOGIC MAPPING OF THE LATE CENOZOIC SEDIMENTS OF THE COLUMBIA BASIN, WASHINGTON by James G. Rigby and Kurt Othberg with contributions from Newell Campbell Larry Hanson Eugene Kiver Dale Stradling Gary Webster Open File Report 79-3 September 1979 State of Washington Department of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resources Olympia, Washington CONTENTS Introduction Objectives Study Area Regional Setting 1 Mapping Procedure 4 Sample Collection 8 Description of Map Units 8 Pre-Miocene Rocks 8 Columbia River Basalt, Yakima Basalt Subgroup 9 Ellensburg Formation 9 Gravels of the Ancestral Columbia River 13 Ringold Formation 15 Thorp Gravel 17 Gravel of Terrace Remnants 19 Tieton Andesite 23 Palouse Formation and Other Loess Deposits 23 Glacial Deposits 25 Catastrophic Flood Deposits 28 Background and previous work 30 Description and interpretation of flood deposits 35 Distinctive geomorphic features 38 Terraces and other features of undetermined origin 40 Post-Pleistocene Deposits 43 Landslide Deposits 44 Alluvium 45 Alluvial Fan Deposits 45 Older Alluvial Fan Deposits 45 Colluvium 46 Sand Dunes 46 Mirna Mounds and Other Periglacial(?) Patterned Ground 47 Structural Geology 48 Southwest Quadrant 48 Toppenish Ridge 49 Ah tanum Ridge 52 Horse Heaven Hills 52 East Selah Fault 53 Northern Saddle Mountains and Smyrna Bench 54 Selah Butte Area 57 Miscellaneous Areas 58 Northwest Quadrant 58 Kittitas Valley 58 Beebe Terrace Disturbance 59 Winesap Lineament 60 Northeast Quadrant 60 Southeast Quadrant 61 Recommendations 62 Stratigraphy 62 Structure 63 Summary 64 References Cited 66 Appendix A - Tephrochronology and identification of collected datable materials 82 Appendix B - Description of field mapping units 88 Northeast Quadrant 89 Northwest Quadrant 90 Southwest Quadrant 91 Southeast Quadrant 92 ii ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1. -

Washington's Channeled Scabland

t\D l'llrl,. \·· ~. r~rn1 ,uR\fEY Ut,l\n . .. ,Y:ltate" tit1Washington ALBEIT D. ROSEWNI, Governor Department of Conservation EARL COE, Dlnctor DIVISION OF MINES AND GEOLOGY MARSHALL T. HUNTTING, Supervisor Bulletin No. 45 WASHINGTON'S CHANNELED SCABLAND By J HARLEN BRETZ 9TAT• PIUHTIHO PLANT ~ OLYMPIA, WASH., 1"511 State of Washington ALBERT D. ROSELLINI, Governor Department of Conservation EARL COE, Director DIVISION OF MINES AND GEOLOGY MARSHALL T. HUNTTING, Supervisor Bulletin No. 45 WASHINGTON'S CHANNELED SCABLAND By .T HARLEN BRETZ l•or sate by Department or Conservation, Olympia, Washington. Price, 50 cents. FOREWORD Most travelers who have driven through eastern Washington have seen a geologic and scenic feature that is unique-nothing like it is to be found anywhere else in the world. This is the Channeled Scab land, a gigantic series of deeply cut channels in the erosion-resistant Columbia River basalt, the rock that covers most of the east-central and southeastern part of the state. Grand Coulee, with its spectac ular Dry Falls, is one of the most widely known features of this ex tensive set of dry channels. Many thousands of travelers must have wondered how this Chan neled Scabland came into being, and many geologists also have speculated as to its origin. Several geologists have published papers outlining their theories of the scabland's origin, but the geologist who has made the most thorough study of the problem and has ex amined the whole area and all the evidence having a bearing on the problem is Dr. J Harlen Bretz. Dr. -

Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail Foundation Document, 2012

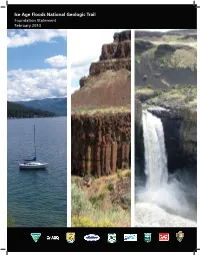

Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail Foundation Statement February 2014 Cover (left to right): Lake Pend Oreille, Farragut State Park, Idaho, NPS Photo Moses Coulee, Washington, NPS Photo Palouse Falls, Washington, NPS Photo Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail Table of Contents Introduction.........................................................................................................................................2 Purpose of this Foundation Statement.................................................................................2 Development of this Foundation Statement........................................................................2 Elements of the Foundation Statement...............................................................................3 Trail Description.......................................................................................................................4 Map..........................................................................................................................................6 Trail Purpose.......................................................................................................................................8 Trail Signifcance................................................................................................................................10 Fundamental Resources and Values.................................................................................................12 Primary Interpretive Themes............................................................................................................22 -

The Holocene

The Holocene http://hol.sagepub.com The Holocene history of bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) in eastern Washington state, northwestern USA R. Lee Lyman The Holocene 2009; 19; 143 DOI: 10.1177/0959683608098958 The online version of this article can be found at: http://hol.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/19/1/143 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for The Holocene can be found at: Email Alerts: http://hol.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://hol.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav Citations http://hol.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/19/1/143 Downloaded from http://hol.sagepub.com at University of Missouri-Columbia on January 13, 2009 The Holocene 19,1 (2009) pp. 143–150 The Holocene history of bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) in eastern Washington state, northwestern USA R. Lee Lyman* (Department of Anthropology, 107 Swallow Hall, University of Missouri-Columbia, Columbia MO 65211, USA) Received 9 May 2008; revised manuscript accepted 30 June 2008 Abstract: Historical data are incomplete regarding the presence/absence and distribution of bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) in eastern Washington State. Palaeozoological (archaeological and palaeontological) data indicate bighorn were present in many areas there during most of the last 10 000 years. Bighorn occupied the xeric shrub-steppe habitats of the Channeled Scablands, likely because the Scablands provided the steep escape terrain bighorn prefer. The relative abundance of bighorn is greatest during climatically dry intervals and low during a moist period. Bighorn remains tend to increase in relative abundance over the last 6000 years. -

Foundation Document, Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail, Montana

Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail DRAFT Foundation Statement September 2011 Cover (left to right): Lake Pend Oreille, Farragut State Park, Idaho, NPS Photo; Moses Coulee, Washington, NPS Photo; Palouse Falls, Washington, NPS Photo 2 Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail Table of Contents Introduction.............................................................................................................................................................4 Trail Description....................................................................................................................................................6 Map..............................................................................................................................................................................8 Trail Purpose.........................................................................................................................................................10 Trail Significance.................................................................................................................................................12 Fundamental Resources and Values..............................................................................................................14 Primary Interpretive Themes..........................................................................................................................24 Special Mandates and Administrative Commitments............................................................................26 -

Late Pleistocene Glacial

---Late Pleistocene Glacial-- -Lakes - of Foster Creek Wmema-n - June, 2001 Knud W. Martin Central Washington University Abstract: Ice age floods scoured, and the Okanogan Lobe of the Cordilleran Icesheet covered, the Foster Creek Watershed of northcentral Washington, in the late Pleistocene. Glacial lakes formed when ice dammed meltwaters from the receding Cordilleran Icesheet filled the Foster Creek Watershed. I mapped the glacial lake sediments along East Foster Creek to understand: 1) the extent of the glacial lake sediments; and 2) how the glacial lake sediments shaped the geomorphology, soils, and land use in the Foster Creek Watershed. I mapped the glacial lake extents using airphoto and topographic map interpretation, and field surveying using a Geodetic Total Station. The lake extents were mapped by the lacustrine sediments upper extents and five glacial lake elevations were found within the Foster Creek Watershed with elevations of 2 124' (upper Foster Creek), 1920'-1940' (mid East Foster Creek), 2 100'(Upper Middle Foster Creek), 1760' (lower Middle and main channel of West foster Creek, and 2220'(upper West Foster Creek). Indicating localized ice dams from the receding Okanogan Lobe impounding the meltwaters, forming glacial lakes. The research is significant in understanding the glacial history, arroyo incision, soil erosion, and badland topography in the watershed. Introduction: As ice from the late Pleistocene Okanogan Lobe of the Cordilleran Icesheet (figures A-E) blocked the drainages once used by the Missoula Floods, lakes formed behind the ice dam, filling the Foster Creek Watershed of northcentral Washington with glacial meltwater. The continued melting of the receding Cordilleran Icesheet caused the meltwater in East, West, and Middle Foster Creeks to swell, forming glacial lakes (figures F-I). -

Megafloods and Clovis Cache at Wenatchee, Washington

Quaternary Research 85 (2016) 430e444 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary Research journal homepage: http://www.journals.elsevier.com/quaternary-research Megafloods and Clovis cache at Wenatchee, Washington Richard B. Waitt U.S. Geological Survey, 1300 SE Cardinal Court, #100, Vancouver, WA 98683, USA article info abstract Article history: Immense late Wisconsin floods from glacial Lake Missoula drowned the Wenatchee reach of Wash- Received 17 June 2015 ington's Columbia valley by different routes. The earliest debacles, nearly 19,000 cal yr BP, raged 335 m deep down the Columbia and built high Pangborn bar at Wenatchee. As advancing ice blocked the northwest of Columbia valley, several giant floods descended Moses Coulee and backflooded up the Keywords: Columbia past Wenatchee. Ice then blocked Moses Coulee, and Grand Coulee to Quincy basin became the fl Missoula oods westmost floodway. From Quincy basin many Missoula floods backflowed 50 km upvalley to Wenatchee Clovis d fl 18,000 to 15,500 years ago. Receding ice dammed glacial Lake Columbia centuries more till it burst Mega oods fl Columbia valley about 15,000 years ago. After Glacier Peak ashfall about 13,600 years ago, smaller great ood(s) swept down the Columbia from glacial Lake Kootenay in British Columbia. The East Wenatchee cache of huge fluted Clovis points had been laid atop Pangborn bar after the Glacier Peak ashfall, then buried by loess. Clovis people came five and a half millennia after the early gigantic Missoula floods, two and a half millennia after the last small Missoula flood, and two millennia after the glacial Lake Columbia flood. -

The Channeled Scablands of the Columbia Plateau Author(S): J

The Channeled Scablands of the Columbia Plateau Author(s): J. Harlen Bretz Source: The Journal of Geology, Vol. 31, No. 8 (Nov. - Dec., 1923), pp. 617-649 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30066357 . Accessed: 16/01/2015 14:23 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Geology. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.193.213.194 on Fri, 16 Jan 2015 14:23:28 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions VOLUME XXXI NUMBER 8 THE JOURNAL oF GEOLOGY November-December 1923 THE CHANNELED SCABLANDS OF THE COLUMBIA PLATEAU J HARLEN BRETZ University of Chicago OUTLINE DEFINITION OF " SCABLAND" PHYSIOGRAPHIC RELATIONS OF THE CHANNELED SCABLANDS GENERALIZED STATEMENT OF THE ORIGIN OF THE CHANNELED SCABLANDS THE BASALT PLAIN, NORTH OF THE SCABLANDS AND THE MATURE TOPOGRAPHY THE MATURE TOPOGRAPHY DETAILS OF A SCABLAND SURFACE ALTITUDES AND GRADIENTS OF THE SCABLAND TRACTS DEPTH OF GLACIAL STREAM EROSION IN THE SCABLANDS Criteria Instances VOLUME OF THE GLACIAL STREAMS DEPOSITS MADE BY THE GLACIAL STREAMS DEPTHS OF SNAKE AND COLUMBIA VALLEYS DURING THE EPOCH THE GLACIATION DEFINITION OF " SCABLAND" The terms "scabland" and "scabrock" are used in the Pacific Northwest to describe areas where denudation has removed or prevented the accumulation of a mantle of soil, and the underlying rock is exposed or covered largely with its own coarse, angular debris. -

Waterville Plateau Field Trip

Ice Age Floods Institute–Ellensburg Chapter Waterville Plateau Field Trip Field Trip Leaders: Karl Lillquist, Geography Department, CWU Nick Zentner, Geological Sciences Department, CWU Sunday 26 September 2010 During the Late Glacial Maximum, the Cordilleran Ice Sheet flowed down both sides of the North Cascades, overwhelming the crest of the range and connecting the Okanogan lobe with Puget Lowland ice across the North Cascades. The Okanogan Lobe reached ~50 km south of the Columbia River on the Waterville Plateau, where it built a massive end moraine and left a museum of glacial landforms magnificently preserved in the arid climate. (Easterbrook, 2003, p. 153) 2 Field Trip Itinerary 8:00 am Depart from CWU’s Hebeler Hall Parking Lot 10:00 Arrive at Stop 1–Dry Falls 11:00 Depart from Dry Falls 11:15 Arrive at Stop 2–”Isaak’s Corner” 11:45 Depart from Isaak’s Corner 12:00 pm Arrive at Stop 3—Sims Corner Esker 12:30 Depart from Sims Corner Esker 1:00 Arrive at Stop 4—Chalk Hills 2:00 Depart from Chalk Hills 2:15 Arrive at Stop 5—Mansfield 2:45 Depart from Mansfield 3:00 Arrive at Stop 6—Withrow 3:30 Depart from Withrow 3:45 Arrive at Stop 7-- Moses Coulee 4:15 Depart from Moses Coulee 6:00 Arrive in Ellensburg 3 4 5 3 6 2 7 1 Figure 1. Our route. Numbers indicate 4 field trip stops (Washington Highway Map). Figure 2. The Columbia Plateau and the areal extent of the Columbia River Basalt Group, the four major structural-tectonic subprovinces (the Yakima Fold Belt, Palouse, Blue Mountains, and Clearwater-Weiser embayments), the Pasco Basin, the Olympic-Wallowa lineament, and the CLEW, which is the central portion of the OWL that passes through the western part of the 5 Columbia Plateau (Reidel & Campbell, 1989, p. -

Analysis of the Management Situation

Analysis of the Management Situation Eastern Washington and San Juan Resource Management Plan March 2011 For More Information Contact: BLM Spokane District Office 1103 N. Fancher Rd. Spokane Valley, WA 99212 Phone: 509-536-1200 Email: [email protected] Or visit the project website: www.blm.gov/or/districts/spokane/plans/ewsjrmp Analysis of the Management Situation Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Purpose of the Analysis of the Management Situation .......................................................................1 1.2 General Description of the Planning Area ..........................................................................................2 Chapter 2 Area Profile ...................................................................................................................................3 2.1 Resources ............................................................................................................................................3 2.1.1 Regional Context ..........................................................................................................................3 2.1.1.1 Physiographic Regions .........................................................................................................3 2.1.1.2 Ecoregions ............................................................................................................................3 2.1.1.3 -

Megafloods and Clovis Cache at Wenatchee, Washington

Quaternary Research 85 (2016) 430e444 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary Research journal homepage: http://www.journals.elsevier.com/quaternary-research Megafloods and Clovis cache at Wenatchee, Washington Richard B. Waitt U.S. Geological Survey, 1300 SE Cardinal Court, #100, Vancouver, WA 98683, USA article info abstract Article history: Immense late Wisconsin floods from glacial Lake Missoula drowned the Wenatchee reach of Wash- Received 17 June 2015 ington's Columbia valley by different routes. The earliest debacles, nearly 19,000 cal yr BP, raged 335 m deep down the Columbia and built high Pangborn bar at Wenatchee. As advancing ice blocked the northwest of Columbia valley, several giant floods descended Moses Coulee and backflooded up the Keywords: Columbia past Wenatchee. Ice then blocked Moses Coulee, and Grand Coulee to Quincy basin became the fl Missoula oods westmost floodway. From Quincy basin many Missoula floods backflowed 50 km upvalley to Wenatchee Clovis d fl 18,000 to 15,500 years ago. Receding ice dammed glacial Lake Columbia centuries more till it burst Mega oods fl Columbia valley about 15,000 years ago. After Glacier Peak ashfall about 13,600 years ago, smaller great ood(s) swept down the Columbia from glacial Lake Kootenay in British Columbia. The East Wenatchee cache of huge fluted Clovis points had been laid atop Pangborn bar after the Glacier Peak ashfall, then buried by loess. Clovis people came five and a half millennia after the early gigantic Missoula floods, two and a half millennia after the last small Missoula flood, and two millennia after the glacial Lake Columbia flood. -

Introduction

Ice Age Floods Study of Alternatives Interpretation section j INTERPRETATION Introduction he Organic Act of 1916, which created the National Park Service, charged the TNPS with not only the task of preserving and protecting the parks’ resources, but also to “provide for the enjoyment of the same.” The “enjoyment” mandate has come to mean interpreting the meaning and value of the parks’ resources to the public. In most cases, interpretation can be provided on-site unless the area is too small or the resources too fragile. The larger the park or area and the larger the number of resources contained in that area, the more complex the interpretation becomes. The challenge within the Ice Age Floods 2. Developing physical and visual access Study Region is to creatively address to specific Floods resources. three major issues: 3. Developing an interpretive 1. Identifying Ice Age Floods resources, framework and program for the which are scattered across a four-state natural and cultural history of the area. These specifically include Floods region. resources related to Glacial Lake Columbia Basin Herald Missoula and to the flooding events associated with ice dam failure. M. Sear/ Tours arranged by the Ice Age Floods Institute bring the visitors face-to-face with the evidence of the Ice Age Floods. At Wilson Creek, the visitor can appreciate Bretz’s analysis and understand the Floods’ impact on the land. 83 F LO E OD G S A E C I Interpretation Area impacted by Glacial Lake Missoula and the Floods 84 Ice Age Floods Study of Alternatives Interpretation 1.