Across the Waterville Plateau

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan GEOLOGY of the SCOTT GLACIER and WISCONSIN RANGE AREAS, CENTRAL TRANSANTARCTIC MOUNTAINS, ANTARCTICA

This dissertation has been /»OOAOO m icrofilm ed exactly as received MINSHEW, Jr., Velon Haywood, 1939- GEOLOGY OF THE SCOTT GLACIER AND WISCONSIN RANGE AREAS, CENTRAL TRANSANTARCTIC MOUNTAINS, ANTARCTICA. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1967 Geology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan GEOLOGY OF THE SCOTT GLACIER AND WISCONSIN RANGE AREAS, CENTRAL TRANSANTARCTIC MOUNTAINS, ANTARCTICA DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Velon Haywood Minshew, Jr. B.S., M.S, The Ohio State University 1967 Approved by -Adviser Department of Geology ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report covers two field seasons in the central Trans- antarctic Mountains, During this time, the Mt, Weaver field party consisted of: George Doumani, leader and paleontologist; Larry Lackey, field assistant; Courtney Skinner, field assistant. The Wisconsin Range party was composed of: Gunter Faure, leader and geochronologist; John Mercer, glacial geologist; John Murtaugh, igneous petrclogist; James Teller, field assistant; Courtney Skinner, field assistant; Harry Gair, visiting strati- grapher. The author served as a stratigrapher with both expedi tions . Various members of the staff of the Department of Geology, The Ohio State University, as well as some specialists from the outside were consulted in the laboratory studies for the pre paration of this report. Dr. George E. Moore supervised the petrographic work and critically reviewed the manuscript. Dr. J. M. Schopf examined the coal and plant fossils, and provided information concerning their age and environmental significance. Drs. Richard P. Goldthwait and Colin B. B. Bull spent time with the author discussing the late Paleozoic glacial deposits, and reviewed portions of the manuscript. -

Washington Division of Geology and Earth Resources Open File Report

RECONNAISSANCE SURFICIAL GEOLOGIC MAPPING OF THE LATE CENOZOIC SEDIMENTS OF THE COLUMBIA BASIN, WASHINGTON by James G. Rigby and Kurt Othberg with contributions from Newell Campbell Larry Hanson Eugene Kiver Dale Stradling Gary Webster Open File Report 79-3 September 1979 State of Washington Department of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resources Olympia, Washington CONTENTS Introduction Objectives Study Area Regional Setting 1 Mapping Procedure 4 Sample Collection 8 Description of Map Units 8 Pre-Miocene Rocks 8 Columbia River Basalt, Yakima Basalt Subgroup 9 Ellensburg Formation 9 Gravels of the Ancestral Columbia River 13 Ringold Formation 15 Thorp Gravel 17 Gravel of Terrace Remnants 19 Tieton Andesite 23 Palouse Formation and Other Loess Deposits 23 Glacial Deposits 25 Catastrophic Flood Deposits 28 Background and previous work 30 Description and interpretation of flood deposits 35 Distinctive geomorphic features 38 Terraces and other features of undetermined origin 40 Post-Pleistocene Deposits 43 Landslide Deposits 44 Alluvium 45 Alluvial Fan Deposits 45 Older Alluvial Fan Deposits 45 Colluvium 46 Sand Dunes 46 Mirna Mounds and Other Periglacial(?) Patterned Ground 47 Structural Geology 48 Southwest Quadrant 48 Toppenish Ridge 49 Ah tanum Ridge 52 Horse Heaven Hills 52 East Selah Fault 53 Northern Saddle Mountains and Smyrna Bench 54 Selah Butte Area 57 Miscellaneous Areas 58 Northwest Quadrant 58 Kittitas Valley 58 Beebe Terrace Disturbance 59 Winesap Lineament 60 Northeast Quadrant 60 Southeast Quadrant 61 Recommendations 62 Stratigraphy 62 Structure 63 Summary 64 References Cited 66 Appendix A - Tephrochronology and identification of collected datable materials 82 Appendix B - Description of field mapping units 88 Northeast Quadrant 89 Northwest Quadrant 90 Southwest Quadrant 91 Southeast Quadrant 92 ii ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1. -

Introduction to Geological Process in Illinois Glacial

INTRODUCTION TO GEOLOGICAL PROCESS IN ILLINOIS GLACIAL PROCESSES AND LANDSCAPES GLACIERS A glacier is a flowing mass of ice. This simple definition covers many possibilities. Glaciers are large, but they can range in size from continent covering (like that occupying Antarctica) to barely covering the head of a mountain valley (like those found in the Grand Tetons and Glacier National Park). No glaciers are found in Illinois; however, they had a profound effect shaping our landscape. More on glaciers: http://www.physicalgeography.net/fundamentals/10ad.html Formation and Movement of Glacial Ice When placed under the appropriate conditions of pressure and temperature, ice will flow. In a glacier, this occurs when the ice is at least 20-50 meters (60 to 150 feet) thick. The buildup results from the accumulation of snow over the course of many years and requires that at least some of each winter’s snowfall does not melt over the following summer. The portion of the glacier where there is a net accumulation of ice and snow from year to year is called the zone of accumulation. The normal rate of glacial movement is a few feet per day, although some glaciers can surge at tens of feet per day. The ice moves by flowing and basal slip. Flow occurs through “plastic deformation” in which the solid ice deforms without melting or breaking. Plastic deformation is much like the slow flow of Silly Putty and can only occur when the ice is under pressure from above. The accumulation of meltwater underneath the glacier can act as a lubricant which allows the ice to slide on its base. -

Washington's Channeled Scabland

t\D l'llrl,. \·· ~. r~rn1 ,uR\fEY Ut,l\n . .. ,Y:ltate" tit1Washington ALBEIT D. ROSEWNI, Governor Department of Conservation EARL COE, Dlnctor DIVISION OF MINES AND GEOLOGY MARSHALL T. HUNTTING, Supervisor Bulletin No. 45 WASHINGTON'S CHANNELED SCABLAND By J HARLEN BRETZ 9TAT• PIUHTIHO PLANT ~ OLYMPIA, WASH., 1"511 State of Washington ALBERT D. ROSELLINI, Governor Department of Conservation EARL COE, Director DIVISION OF MINES AND GEOLOGY MARSHALL T. HUNTTING, Supervisor Bulletin No. 45 WASHINGTON'S CHANNELED SCABLAND By .T HARLEN BRETZ l•or sate by Department or Conservation, Olympia, Washington. Price, 50 cents. FOREWORD Most travelers who have driven through eastern Washington have seen a geologic and scenic feature that is unique-nothing like it is to be found anywhere else in the world. This is the Channeled Scab land, a gigantic series of deeply cut channels in the erosion-resistant Columbia River basalt, the rock that covers most of the east-central and southeastern part of the state. Grand Coulee, with its spectac ular Dry Falls, is one of the most widely known features of this ex tensive set of dry channels. Many thousands of travelers must have wondered how this Chan neled Scabland came into being, and many geologists also have speculated as to its origin. Several geologists have published papers outlining their theories of the scabland's origin, but the geologist who has made the most thorough study of the problem and has ex amined the whole area and all the evidence having a bearing on the problem is Dr. J Harlen Bretz. Dr. -

Geologic Map of the Coupeville and Part of the Port Townsend North 7.5

WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES GEOLOGIC MAP GM-58 Geologic Map of the Coupeville and Part of the Port Townsend North R1W R1E 42¢30² 122°45¢ 40¢ 122°37¢30² 48°15¢ 48°15¢ Qgtv Qco Qb Qgoge Qco Qgdp 7.5-minute Quadrangles, Island County, Washington Qml 1 Qco schematic section Qgog Qgd 5 e Qcw from top to Qgav; Qgav Qgdme elev. 197 ft schematic section elev. 160 ft measured section Qgdp Qml Qgav Qgoge elev. 150 ft Qs <10 ft sand by Michael Polenz, Stephen L. Slaughter, and Gerald W. Thorsen ~10 ft below Qgav Qd active dune sand Qp Qs 110,124,182 6 to 12 ft 5 ft Qs sand Qgdm 18 ft sand and gravel Qgdm Qco silt and clay e Qgav 7 ft Qgdm diamict e Qb liquefaction features e Qgdme Qml Qc 15 ft silt 9 ft Qgd diamict Qcw o and small shears in Qd Qgoge Qgd 9 ft Qgt till 188 p 10 ft silt and clay silt and sand at ~100 ft June 2005 v Qgtv <75 ft Qgoge 11 ft Qgav sandy gravel Qcw Qp Qmw 177,178 gravel with ~30 ft mixed deposits—sand, Qmw silt boulders silt, and minor gravel Qgd Qp Qgomee? Qm Qgdmels? ~20 ft lahar runout (Table 2, samples 188 and 182*) GEOLOGIC SETTING AND DEVELOPMENT We suggest that this sediment source is partly documented by a high-energy outwash Deposits of the Fraser Glaciation (Pleistocene) alluvial facies reflect ancestral Skagit River provenance. Sparse, local Glacier REFERENCES CITED channel deposits— Qgomee Qcw Qgd 79 ft p clean sand with Qls Qb Qcw ~15 ft channel deposits—sand and minor gravel gravel unit (unit Qgoge), which locally grades up into Partridge Gravel, and which we Peak dacite and pumice pebbles, such as those found to the east of Long Point very sparse gravel Like most of the Puget Lowland, the map area is dominated by glacial sediment and lacks Armstrong, J. -

Erosional and Depositional Study Guide

Erosional and Depositional Study Guide Erosional 32. (2pts) Name the two ways glaciers erode the bed. 33. (6pts) Explain abrasion. Use the equation for abrasion to frame your answer. 34. (3pts) Contrast the hardness of ice compared to the hardness of bedrock. What is doing the abrading and why? 35. (3pts) Contrast the normal stress (weight of the ice) on the rock tool in the ice compared to the contact pressure. Are they the same, different? Why? 36. (3pts) The tools in the ice abrade along with the bedrock so the tools must be replenished for the glacier to erode over its entire base. What is the source of the tools? Explain. 37. (3pts) What is the role of subglacial hydrology in abrasion? Explain. 38. (3pts) Although we did not explicitly discuss this in class, consider abrasion and bulk erosion in a deforming subglacial till. Explain what might be happening. 39. (2 pts) Name the two ways plucking occurs. 40. (5pts) Explain how plucking occurs at a step in the bedrock. 41. (3pts) What is a roche mountonee and how does it form? 42. (3pts) Name 3 erosional landscapes created by glaciers. Do not include roche mountonee and U-shaped valley. 43. (6pts) How does a U-shaped valley form? Be specific. Depositional 44. (3pts) How does a glacier transport rock debris? 45. (3pts) Where do you find lateral moraines on a glacier and what glacial processes determine their location? Draw a plan view diagram of a glacier, identify its relevant parts and the locations of lateral moraines. 46. (3pts) In class we discussed how the vertical extent of moraines is not correlated with glacier size. -

Glacial Processes and Landforms

Glacial Processes and Landforms I. INTRODUCTION A. Definitions 1. Glacier- a thick mass of flowing/moving ice a. glaciers originate on land from the compaction and recrystallization of snow, thus are generated in areas favored by a climate in which seasonal snow accumulation is greater than seasonal melting (1) polar regions (2) high altitude/mountainous regions 2. Snowfield- a region that displays a net annual accumulation of snow a. snowline- imaginary line defining the limits of snow accumulation in a snowfield. (1) above which continuous, positive snow cover 3. Water balance- in general the hydrologic cycle involves water evaporated from sea, carried to land, precipitation, water carried back to sea via rivers and underground a. water becomes locked up or frozen in glaciers, thus temporarily removed from the hydrologic cycle (1) thus in times of great accumulation of glacial ice, sea level would tend to be lower than in times of no glacial ice. II. FORMATION OF GLACIAL ICE A. Process: Formation of glacial ice: snow crystallizes from atmospheric moisture, accumulates on surface of earth. As snow is accumulated, snow crystals become compacted > in density, with air forced out of pack. 1. Snow accumulates seasonally: delicate frozen crystal structure a. Low density: ~0.1 gm/cu. cm b. Transformation: snow compaction, pressure solution of flakes, percolation of meltwater c. Freezing and recrystallization > density 2. Firn- compacted snow with D = 0.5D water a. With further compaction, D >, firn ---------ice. b. Crystal fabrics oriented and aligned under weight of compaction 3. Ice: compacted firn with density approaching 1 gm/cu. cm a. -

Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail Foundation Document, 2012

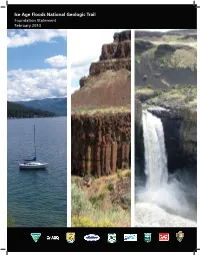

Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail Foundation Statement February 2014 Cover (left to right): Lake Pend Oreille, Farragut State Park, Idaho, NPS Photo Moses Coulee, Washington, NPS Photo Palouse Falls, Washington, NPS Photo Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail Table of Contents Introduction.........................................................................................................................................2 Purpose of this Foundation Statement.................................................................................2 Development of this Foundation Statement........................................................................2 Elements of the Foundation Statement...............................................................................3 Trail Description.......................................................................................................................4 Map..........................................................................................................................................6 Trail Purpose.......................................................................................................................................8 Trail Signifcance................................................................................................................................10 Fundamental Resources and Values.................................................................................................12 Primary Interpretive Themes............................................................................................................22 -

The Holocene

The Holocene http://hol.sagepub.com The Holocene history of bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) in eastern Washington state, northwestern USA R. Lee Lyman The Holocene 2009; 19; 143 DOI: 10.1177/0959683608098958 The online version of this article can be found at: http://hol.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/19/1/143 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for The Holocene can be found at: Email Alerts: http://hol.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://hol.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav Citations http://hol.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/19/1/143 Downloaded from http://hol.sagepub.com at University of Missouri-Columbia on January 13, 2009 The Holocene 19,1 (2009) pp. 143–150 The Holocene history of bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) in eastern Washington state, northwestern USA R. Lee Lyman* (Department of Anthropology, 107 Swallow Hall, University of Missouri-Columbia, Columbia MO 65211, USA) Received 9 May 2008; revised manuscript accepted 30 June 2008 Abstract: Historical data are incomplete regarding the presence/absence and distribution of bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) in eastern Washington State. Palaeozoological (archaeological and palaeontological) data indicate bighorn were present in many areas there during most of the last 10 000 years. Bighorn occupied the xeric shrub-steppe habitats of the Channeled Scablands, likely because the Scablands provided the steep escape terrain bighorn prefer. The relative abundance of bighorn is greatest during climatically dry intervals and low during a moist period. Bighorn remains tend to increase in relative abundance over the last 6000 years. -

Glaciers and Glaciation

M18_TARB6927_09_SE_C18.QXD 1/16/07 4:41 PM Page 482 M18_TARB6927_09_SE_C18.QXD 1/16/07 4:41 PM Page 483 Glaciers and Glaciation CHAPTER 18 A small boat nears the seaward margin of an Antarctic glacier. (Photo by Sergio Pitamitz/ CORBIS) 483 M18_TARB6927_09_SE_C18.QXD 1/16/07 4:41 PM Page 484 limate has a strong influence on the nature and intensity of Earth’s external processes. This fact is dramatically illustrated in this chapter because the C existence and extent of glaciers is largely controlled by Earth’s changing climate. Like the running water and groundwater that were the focus of the preceding two chap- ters, glaciers represent a significant erosional process. These moving masses of ice are re- sponsible for creating many unique landforms and are part of an important link in the rock cycle in which the products of weathering are transported and deposited as sediment. Today glaciers cover nearly 10 percent of Earth’s land surface; however, in the recent ge- ologic past, ice sheets were three times more extensive, covering vast areas with ice thou- sands of meters thick. Many regions still bear the mark of these glaciers (Figure 18.1). The basic character of such diverse places as the Alps, Cape Cod, and Yosemite Valley was fashioned by now vanished masses of glacial ice. Moreover, Long Island, the Great Lakes, and the fiords of Norway and Alaska all owe their existence to glaciers. Glaciers, of course, are not just a phenomenon of the geologic past. As you will see, they are still sculpting and depositing debris in many regions today. -

A Geomorphic Classification System

A Geomorphic Classification System U.S.D.A. Forest Service Geomorphology Working Group Haskins, Donald M.1, Correll, Cynthia S.2, Foster, Richard A.3, Chatoian, John M.4, Fincher, James M.5, Strenger, Steven 6, Keys, James E. Jr.7, Maxwell, James R.8 and King, Thomas 9 February 1998 Version 1.4 1 Forest Geologist, Shasta-Trinity National Forests, Pacific Southwest Region, Redding, CA; 2 Soil Scientist, Range Staff, Washington Office, Prineville, OR; 3 Area Soil Scientist, Chatham Area, Tongass National Forest, Alaska Region, Sitka, AK; 4 Regional Geologist, Pacific Southwest Region, San Francisco, CA; 5 Integrated Resource Inventory Program Manager, Alaska Region, Juneau, AK; 6 Supervisory Soil Scientist, Southwest Region, Albuquerque, NM; 7 Interagency Liaison for Washington Office ECOMAP Group, Southern Region, Atlanta, GA; 8 Water Program Leader, Rocky Mountain Region, Golden, CO; and 9 Geology Program Manager, Washington Office, Washington, DC. A Geomorphic Classification System 1 Table of Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... 5 I. INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................. 6 History of Classification Efforts in the Forest Service ............................................................... 6 History of Development .............................................................................................................. 7 Goals -

Soil Crusts of Moses Coulee Area Washington

Soil Crusts of Moses Coulee Area Washington Daphne Stone, Robert Smith and Amanda Hardman NW Lichenologists 2013-2014 Texosporium sancti-jacobi Introduction Biological soil crusts are a close association between soil particles and cyanobacteria, microfungi, algae, lichens and bryophytes (Belknap et al. 2001). They are known to be widespread across the arid lands of southern and western North America, where they reduce non-native plant invasion, aid in soil and water retention, reduce erosion and fix nitrogen, making this often growth-limiting nutrient available to the ecosystem (Belknap et al. 2001). On the other hand, soil crusts are just beginning to be explored in the Pacific Northwest. The earliest surveys were at Horse Heaven Hills in south-central Washington (Ponzetti et al. 2007). Now several areas in central Oregon, from the Columbia River basin in the north to the Lakeview BLM District in south central Oregon (Miller et al. 2011, Root and McCune 2012, Stone, unpublished Lakeview BLM reports 2013 and 2014 and Malheur N. F. 2014), have been surveyed. The central area of Washington, which includes many acres of steppe habitat in channeled scablands created by the Missoula Floods, has not previously been surveyed. Much of this land has been grazed, and some small areas remain undisturbed or have been closed to grazing recently. The purpose of this study was to survey intensively at sites with different levels of grazing activity, at different elevations, and in different habitats, in order to gain some understanding of what soil crust lichen and bryophyte species are present, the extent of the soil crusts, and the quality of different habitats.