The Holocene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washington Division of Geology and Earth Resources Open File Report

RECONNAISSANCE SURFICIAL GEOLOGIC MAPPING OF THE LATE CENOZOIC SEDIMENTS OF THE COLUMBIA BASIN, WASHINGTON by James G. Rigby and Kurt Othberg with contributions from Newell Campbell Larry Hanson Eugene Kiver Dale Stradling Gary Webster Open File Report 79-3 September 1979 State of Washington Department of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resources Olympia, Washington CONTENTS Introduction Objectives Study Area Regional Setting 1 Mapping Procedure 4 Sample Collection 8 Description of Map Units 8 Pre-Miocene Rocks 8 Columbia River Basalt, Yakima Basalt Subgroup 9 Ellensburg Formation 9 Gravels of the Ancestral Columbia River 13 Ringold Formation 15 Thorp Gravel 17 Gravel of Terrace Remnants 19 Tieton Andesite 23 Palouse Formation and Other Loess Deposits 23 Glacial Deposits 25 Catastrophic Flood Deposits 28 Background and previous work 30 Description and interpretation of flood deposits 35 Distinctive geomorphic features 38 Terraces and other features of undetermined origin 40 Post-Pleistocene Deposits 43 Landslide Deposits 44 Alluvium 45 Alluvial Fan Deposits 45 Older Alluvial Fan Deposits 45 Colluvium 46 Sand Dunes 46 Mirna Mounds and Other Periglacial(?) Patterned Ground 47 Structural Geology 48 Southwest Quadrant 48 Toppenish Ridge 49 Ah tanum Ridge 52 Horse Heaven Hills 52 East Selah Fault 53 Northern Saddle Mountains and Smyrna Bench 54 Selah Butte Area 57 Miscellaneous Areas 58 Northwest Quadrant 58 Kittitas Valley 58 Beebe Terrace Disturbance 59 Winesap Lineament 60 Northeast Quadrant 60 Southeast Quadrant 61 Recommendations 62 Stratigraphy 62 Structure 63 Summary 64 References Cited 66 Appendix A - Tephrochronology and identification of collected datable materials 82 Appendix B - Description of field mapping units 88 Northeast Quadrant 89 Northwest Quadrant 90 Southwest Quadrant 91 Southeast Quadrant 92 ii ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1. -

Mizzoualumnus1975novp16-19.Pdf (3.318Mb)

THE GAUE THAT TRAPPED HISTORY Natural Trap Cave has been collecting bones of unwary animals for at least 13,000 years. Expeditions led by a Mizzou anthropologist are digging up those bones and clues about the cycles of climatic change. Text and Photos by Dave Holman IIi / m ISSOllRI ilLUrnrus The only entrenee to Natural Trap Ceve la the hole In the roof. Any enlmal that might have survived the fallatlll became a victim. Workera at theahe, below, ehherrappellnto theeave or descend theacafloldlng. A herd of small horses stampeded through the tall grass across a plateau near the edge of a canyon, pur sued by a large, long-legged cat. The cat closed on the slowest horse, forcing her along the canyon edge onto a peninsula of limestone. The cat sprang, fas tened its claws and teeth in the horse's neck, and suddenly, horse and cat disappeared from the face of the earth. Twelve thousand years later, a green panel truck and a dusty jeep bounced along a dirt road over the same plateau, now covered with sage and prickly pear. On the limestone peninsula where the horse and cat disappeared, the vehicles stopped by a 15- foot-wide hole in the rock. Eighty feet below is the floor of Natural Trap Cave. The cave floor is covered with the accumulated dust of centuries, clearly stratified and containing thou sands of bones of animals that failed to see the hole. This summer was the second consecutive year that Bob Gilbert, research associate in Mizzou's an thropology department had led an organized ex pedition to the trap. -

Washington's Channeled Scabland

t\D l'llrl,. \·· ~. r~rn1 ,uR\fEY Ut,l\n . .. ,Y:ltate" tit1Washington ALBEIT D. ROSEWNI, Governor Department of Conservation EARL COE, Dlnctor DIVISION OF MINES AND GEOLOGY MARSHALL T. HUNTTING, Supervisor Bulletin No. 45 WASHINGTON'S CHANNELED SCABLAND By J HARLEN BRETZ 9TAT• PIUHTIHO PLANT ~ OLYMPIA, WASH., 1"511 State of Washington ALBERT D. ROSELLINI, Governor Department of Conservation EARL COE, Director DIVISION OF MINES AND GEOLOGY MARSHALL T. HUNTTING, Supervisor Bulletin No. 45 WASHINGTON'S CHANNELED SCABLAND By .T HARLEN BRETZ l•or sate by Department or Conservation, Olympia, Washington. Price, 50 cents. FOREWORD Most travelers who have driven through eastern Washington have seen a geologic and scenic feature that is unique-nothing like it is to be found anywhere else in the world. This is the Channeled Scab land, a gigantic series of deeply cut channels in the erosion-resistant Columbia River basalt, the rock that covers most of the east-central and southeastern part of the state. Grand Coulee, with its spectac ular Dry Falls, is one of the most widely known features of this ex tensive set of dry channels. Many thousands of travelers must have wondered how this Chan neled Scabland came into being, and many geologists also have speculated as to its origin. Several geologists have published papers outlining their theories of the scabland's origin, but the geologist who has made the most thorough study of the problem and has ex amined the whole area and all the evidence having a bearing on the problem is Dr. J Harlen Bretz. Dr. -

Quaternary Records of the Dire Wolf, Canis Dirus, in North and South America

Quaternary records of the dire wolf, Canis dirus, in North and South America ROBERT G. DUNDAS Dundas, R. G. 1999 (September): Quaternary records of the dire wolf, Canis dirus, in North and South Ameri- ca. Boreas, Vol. 28, pp. 375–385. Oslo. ISSN 0300-9483. The dire wolf was an important large, late Pleistocene predator in North and South America, well adapted to preying on megaherbivores. Geographically widespread, Canis dirus is reported from 136 localities in North America from Alberta, Canada, southward and from three localities in South America (Muaco, Venezuela; Ta- lara, Peru; and Tarija, Bolivia). The species lived in a variety of environments, from forested mountains to open grasslands and plains ranging in elevation from sea level to 2255 m (7400 feet). Canis dirus is assigned to the Rancholabrean land mammal age of North America and the Lujanian land mammal age of South Amer- ica and was among the many large carnivores and megaherbivores that became extinct in North and South America near the end of the Pleistocene Epoch. Robert G. Dundas, Department of Geology, California State University, Fresno, California 93740-8031, USA. E-mail: [email protected]; received 20th May 1998, accepted 23rd March 1999 Because of the large number of Canis dirus localities Rancho La Brea, comparing them with Canis lupus and and individuals recovered from the fossil record, the dire wolf specimens from other localities. Although dire wolf is the most commonly occurring large knowledge of the animal’s biology had greatly predator in the Pleistocene of North America. By increased by 1912, little was known about its strati- contrast, the species is rare in South America. -

Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail Foundation Document, 2012

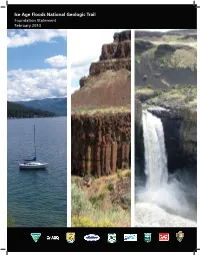

Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail Foundation Statement February 2014 Cover (left to right): Lake Pend Oreille, Farragut State Park, Idaho, NPS Photo Moses Coulee, Washington, NPS Photo Palouse Falls, Washington, NPS Photo Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail Table of Contents Introduction.........................................................................................................................................2 Purpose of this Foundation Statement.................................................................................2 Development of this Foundation Statement........................................................................2 Elements of the Foundation Statement...............................................................................3 Trail Description.......................................................................................................................4 Map..........................................................................................................................................6 Trail Purpose.......................................................................................................................................8 Trail Signifcance................................................................................................................................10 Fundamental Resources and Values.................................................................................................12 Primary Interpretive Themes............................................................................................................22 -

Frequency of Pathology in a Large Natural Sample from Natural Trap

Reumatismo, 2003; 55(1):58-65 RUBRICA DALLA RICERCA ALLA PRATICA Frequency of pathology in a large natural sample from Natural Trap Cave with special remarks on erosive disease in the Pleistocene La patologia osteoarticolare, con particolare riguardo a quella di tipo erosivo, nel Pleistocene: studio di un campione di reperti paleopatologici provenienti dalla Natural Trap Cave (Wyoming, USA) B.M. Rothschild1, L.D. Martin2 1The Arthritis Center of Northeast Ohio, University of Kansas Museum of Natural History, Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine and University of Akron; 2Museum of Natural History and Department of Systematics and Ecology, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 66045 RIASSUNTO Nel presente studio vengono riportati i rilievi paleopatologici, con particolare riguardo alla presenza di artrite ero- siva, di osteoartrosi, di DISH , nonché ai segni di danno della dentizione, relativi ad un’ampia popolazione di mam- miferi, i cui resti (più di 30.000 ossa di 24 specie diverse) sono stati ritrovati nella Natural Trap Cave, Wyoming, USA. L’evidenza di artrite erosiva è confinata ai bovidi, Bison, Ovis e Bootherium, fatto osservabile anche in bisonti del tardo Pleistocene ritrovati nel Kansas (Twelve Mile Creek) e in un’altra località del Wisconsin, riferibile cronologi- camente al primo Olocene. Questi dati, ovvero la restrizione di tali segni di patologia articolare ad un singolo gene- re animale (Bovidi) e ad un determinato periodo storico, rende plausibile l’ipotesi che un agente patogeno, identifi- cabile col Mycobacterium tubercolosis, possa essere stato implicato nella genesi dell’artrite erosiva. Osteoartrosi e DISH sono risultate poco rappresentate nella popolazione animale della Natural Trap Cave, anche se il genere Bi- son ha dimostrato una discreta prevalenza di segni di osteoartrosi. -

Soil Crusts of Moses Coulee Area Washington

Soil Crusts of Moses Coulee Area Washington Daphne Stone, Robert Smith and Amanda Hardman NW Lichenologists 2013-2014 Texosporium sancti-jacobi Introduction Biological soil crusts are a close association between soil particles and cyanobacteria, microfungi, algae, lichens and bryophytes (Belknap et al. 2001). They are known to be widespread across the arid lands of southern and western North America, where they reduce non-native plant invasion, aid in soil and water retention, reduce erosion and fix nitrogen, making this often growth-limiting nutrient available to the ecosystem (Belknap et al. 2001). On the other hand, soil crusts are just beginning to be explored in the Pacific Northwest. The earliest surveys were at Horse Heaven Hills in south-central Washington (Ponzetti et al. 2007). Now several areas in central Oregon, from the Columbia River basin in the north to the Lakeview BLM District in south central Oregon (Miller et al. 2011, Root and McCune 2012, Stone, unpublished Lakeview BLM reports 2013 and 2014 and Malheur N. F. 2014), have been surveyed. The central area of Washington, which includes many acres of steppe habitat in channeled scablands created by the Missoula Floods, has not previously been surveyed. Much of this land has been grazed, and some small areas remain undisturbed or have been closed to grazing recently. The purpose of this study was to survey intensively at sites with different levels of grazing activity, at different elevations, and in different habitats, in order to gain some understanding of what soil crust lichen and bryophyte species are present, the extent of the soil crusts, and the quality of different habitats. -

Small Mammal Faunal Stasis in Natural Trap Cave (Pleistocene– Holocene), Bighorn Mountains, Wyoming

SMALL MAMMAL FAUNAL STASIS IN NATURAL TRAP CAVE (PLEISTOCENE– HOLOCENE), BIGHORN MOUNTAINS, WYOMING BY C2009 Daniel R. Williams Submitted to the graduate degree program in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________ Larry D. Martin/Chairperson Committee members* _____________________* Bruce S. Lieberman _____________________* Robert M. Timm _____________________* Bryan L. Foster _____________________* William C. Johnson Date defended: April 21, 2009 ii The Dissertation Committee for Daniel Williams certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: SMALL MAMMAL FAUNAL STASIS IN NATURAL TRAP CAVE (PLEISTOCENE– HOLOCENE), BIGHORN MOUNTAINS, WYOMING Commmittee: ____________________________________ Larry D. Martin/Chairperson* ____________________________________ Bruce S. Lieberman ____________________________________ Robert M. Timm ____________________________________ Bryan L. Foster ____________________________________ William C. Johnson Date approved: April, 29, 2009 iii ABSTRACT Paleocommunity behavior through time is a topic of fierce debate in paleoecology, one with ramifications for the general study of macroevolution. The predominant viewpoint is that communities are ephemeral objects during the Quaternary that easily fall apart, but evidence exists that suggests geography and spatial scale plays a role. Natural Trap Cave is a prime testing ground for observing how paleocommunities react to large-scale climate change. Natural Trap Cave has a continuous faunal record (100 ka–recent) that spans the last glacial cycle, large portions of which are replicated in local rockshelters, which is used here to test for local causes of stasis. The Quaternary fauna of North America is relatively well sampled and dated, so the influence of spatial scale and biogeography on local community change can also be tested for. -

Rancholabrean Vertebrates from the Las Vegas Formation, Nevada

Quaternary International xxx (2017) 1e17 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint The Tule Springs local fauna: Rancholabrean vertebrates from the Las Vegas Formation, Nevada * Eric Scott a, , Kathleen B. Springer b, James C. Sagebiel c a Dr. John D. Cooper Archaeological and Paleontological Center, California State University, Fullerton, CA 92834, USA b U.S. Geological Survey, Denver Federal Center, Box 25046, MS-980, Denver CO 80225, USA c Vertebrate Paleontology Laboratory, University of Texas at Austin R7600, 10100 Burnet Road, Building 6, Austin, TX 78758, USA article info abstract Article history: A middle to late Pleistocene sedimentary sequence in the upper Las Vegas Wash, north of Las Vegas, Received 8 March 2017 Nevada, has yielded the largest open-site Rancholabrean vertebrate fossil assemblage in the southern Received in revised form Great Basin and Mojave Deserts. Recent paleontologic field studies have led to the discovery of hundreds 19 May 2017 of fossil localities and specimens, greatly extending the geographic and temporal footprint of original Accepted 2 June 2017 investigations in the early 1960s. The significance of the deposits and their entombed fossils led to the Available online xxx preservation of 22,650 acres of the upper Las Vegas Wash as Tule Springs Fossil Beds National Monu- ment. These discoveries also warrant designation of the assemblage as a local fauna, named for the site of the original paleontologic studies at Tule Springs. The large mammal component of the Tule Springs local fauna is dominated by remains of Mammuthus columbi as well as Camelops hesternus, along with less common remains of Equus (including E. -

Foundation Document, Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail, Montana

Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail DRAFT Foundation Statement September 2011 Cover (left to right): Lake Pend Oreille, Farragut State Park, Idaho, NPS Photo; Moses Coulee, Washington, NPS Photo; Palouse Falls, Washington, NPS Photo 2 Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail Table of Contents Introduction.............................................................................................................................................................4 Trail Description....................................................................................................................................................6 Map..............................................................................................................................................................................8 Trail Purpose.........................................................................................................................................................10 Trail Significance.................................................................................................................................................12 Fundamental Resources and Values..............................................................................................................14 Primary Interpretive Themes..........................................................................................................................24 Special Mandates and Administrative Commitments............................................................................26 -

ABSTRACT Comparing the Genetic Diversity of Late Pleistocene Bison

ABSTRACT Comparing the Genetic Diversity of Late Pleistocene Bison with Modern Bison bison Using Ancient DNA Techniques and the Mitochondrial DNA Control Region Kory C. Douglas Mentors: Robert P. Adams, Ph.D., and Lori E. Baker, Ph.D. The transition between the Pleistocene and Holocene Epochs brought about a mass extinction of many large mammals. The genetic consequences of such widespread extinctions have not been well studied. Using ancient DNA and phylogenetic techniques, the genetic diversity and phylogenetic relatedness of extinct Pleistocene Bison ranging from Siberia to mid-latitude North America (10,000 ybp to 50,000 ybp) were compared to extant Bison bison. The mitochondrial DNA control region was sequenced from 10 Bison priscus skulls obtained from the Kolyma Region of Siberia, Russia. Control region sequences from other Pleistocene Bison species and Bison bison were obtained from Genbank. There is a measurable loss of genetic diversity in Bison bison compared to Pleistocene Bison. Furthermore, the Pleistocene Bison population was strongest in North America from a time period of 30,000 ybp to 10,000 ybp, and the genetic diversity present in this population is not represented in the Bison bison population. Copyright © 2006 Kory C. Douglas All rights reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures iv List of Tables v Acknowledgments vi Chapter One: Introduction 1 Ancient DNA 2 Mitochondrial DNA 3 Pleistocene Epoch 5 Mass Extinctions 8 Bison 10 Phylogenetics 11 Research Hypotheses 14 Chapter Two: Materials and Methods 16 Sampling 16 -

A Wild Boar Dominated Ungulate Assemblage from an Early Holocene Natural Pit Fall Trap

596837 HOL0010.1177/0959683615596837The HoloceneLord et al. research-article2015 Research report The Holocene 1 –7 A wild boar dominated ungulate © The Author(s) 2015 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav assemblage from an early Holocene DOI: 10.1177/0959683615596837 natural pit fall trap: Cave shaft hol.sagepub.com sediments in northwest England associated with the 9.3 ka BP cold event Tom C Lord,1 John A Thorp2 and Peter Wilson3 Abstract A highly unusual pit fall ungulate assemblage dominated by wild boar (Sus scrofa) was recovered during the recent exploration of a cave shaft in the upland karstic landscape of northwest England. Both the opening of the cave shaft to the surface and its infilling by clastic sediments are attributable to accelerated landscape erosion associated with the 9.3 ka BP climatic deterioration. Evidence that wild boar had died in winter or spring suggests that their deaths relate to the prolonged periods of annual snow cover experienced by the uplands of northwest England during the 9.3 ka BP event. The dominance of wild boar in the pit fall assemblage is explained by the snow pack concealing the open shaft and turning it into a baited trap for wild boar whenever it contained carrion. Wild boar bones splintered and chewed by wild boar demonstrate carrion cannibalism. Human presence is attested by slight butchery to an aurochs (Bos primigenius). How Mesolithic people adapted to climate change associated with the 9.3 ka BP event is a subject well worth pursuing. Keywords 9.3 ka BP event, animal bones, karstic caves, northwest England Received 9 March 2015; revised manuscript accepted 6 June 2015 Introduction as Sites of Special Scientific Interest (Hinde et al., 2012).