South Georgia Andrew Clarke, John P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Georgia and Antarctic Odyssey

South Georgia and Antarctic Odyssey 30 November – 18 December 2019 | Greg Mortimer About Us Aurora Expeditions embodies the spirit of adventure, travelling to some of the most wild opportunity for adventure and discovery. Our highly experienced expedition team of and remote places on our planet. With over 28 years’ experience, our small group voyages naturalists, historians and destination specialists are passionate and knowledgeable – they allow for a truly intimate experience with nature. are the secret to a fulfilling and successful voyage. Our expeditions push the boundaries with flexible and innovative itineraries, exciting Whilst we are dedicated to providing a ‘trip of a lifetime’, we are also deeply committed to wildlife experiences and fascinating lectures. You’ll share your adventure with a group education and preservation of the environment. Our aim is to travel respectfully, creating of like-minded souls in a relaxed, casual atmosphere while making the most of every lifelong ambassadors for the protection of our destinations. DAY 1 | Saturday 30 November 2019 Ushuaia, Beagle Channel Position: 20:00 hours Course: 83° Wind Speed: 20 knots Barometer: 991 hPa & steady Latitude: 54°49’ S Wind Direction: W Air Temp: 6° C Longitude: 68°18’ W Sea Temp: 5° C Explore. Dream. Discover. —Mark Twain in the soft afternoon light. The wildlife bonanza was off to a good start with a plethora of seabirds circling the ship as we departed. Finally we are here on the Beagle Channel aboard our sparkling new ice-strengthened vessel. This afternoon in the wharf in Ushuaia we were treated to a true polar welcome, with On our port side stretched the beech forested slopes of Argentina, while Chile, its mountain an invigorating breeze sweeping the cobwebs of travel away. -

Lista Roja De Las Aves Del Uruguay 1

Lista Roja de las Aves del Uruguay 1 Lista Roja de las Aves del Uruguay Una evaluación del estado de conservación de la avifauna nacional con base en los criterios de la Unión Internacional para la Conservación de la Naturaleza. Adrián B. Azpiroz, Laboratorio de Genética de la Conservación, Instituto de Investigaciones Biológicas Clemente Estable, Av. Italia 3318 (CP 11600), Montevideo ([email protected]). Matilde Alfaro, Asociación Averaves & Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de la República, Iguá 4225 (CP 11400), Montevideo ([email protected]). Sebastián Jiménez, Proyecto Albatros y Petreles-Uruguay, Centro de Investigación y Conservación Marina (CICMAR), Avenida Giannattasio Km 30.5. (CP 15008) Canelones, Uruguay; Laboratorio de Recursos Pelágicos, Dirección Nacional de Recursos Acuáticos, Constituyente 1497 (CP 11200), Montevideo ([email protected]). Cita sugerida: Azpiroz, A.B., M. Alfaro y S. Jiménez. 2012. Lista Roja de las Aves del Uruguay. Una evaluación del estado de conservación de la avifauna nacional con base en los criterios de la Unión Internacional para la Conservación de la Naturaleza. Dirección Nacional de Medio Ambiente, Montevideo. Descargo de responsabilidad El contenido de esta publicación es responsabilidad de los autores y no refleja necesariamente las opiniones o políticas de la DINAMA ni de las organizaciones auspiciantes y no comprometen a estas instituciones. Las denominaciones empleadas y la forma en que aparecen los datos no implica de parte de DINAMA, ni de las organizaciones auspiciantes o de los autores, juicio alguno sobre la condición jurídica de países, territorios, ciudades, personas, organizaciones, zonas o de sus autoridades, ni sobre la delimitación de sus fronteras o límites. -

Antarctica, South Georgia & the Falkland Islands

Antarctica, South Georgia & the Falkland Islands January 5 - 26, 2017 ARGENTINA Saunders Island Fortuna Bay Steeple Jason Island Stromness Bay Grytviken Tierra del Fuego FALKLAND SOUTH Gold Harbour ISLANDS GEORGIA CHILE SCOTIA SEA Drygalski Fjord Ushuaia Elephant Island DRAKE Livingston Island Deception PASSAGE Island LEMAIRE CHANNEL Cuverville Island ANTARCTIC PENINSULA Friday & Saturday, January 6 & 7, 2017 Ushuaia, Argentina / Beagle Channel / Embark Ocean Diamond Ushuaia, ‘Fin del Mundo,’ at the southernmost tip of Argentina was where we gathered for the start of our Antarctic adventure, and after a night’s rest, we set out on various excursions to explore the neighborhood of the end of the world. The keen birders were the first away, on their mission to the Tierra del Fuego National Park in search of the Magellanic woodpecker. They were rewarded with sightings of both male and female woodpeckers, Andean condors, flocks of Austral parakeets, and a wonderful view of an Austral pygmy owl, as well as a wide variety of other birds to check off their lists. The majority of our group went off on a catamaran tour of the Beagle Channel, where we saw South American sea lions on offshore islands before sailing on to the national park for a walk along the shore and an enjoyable Argentinian BBQ lunch. Others chose to hike in the deciduous beech forests of Reserva Natural Cerro Alarkén around the Arakur Resort & Spa. After only a few minutes of hiking, we saw an Andean condor soar above us and watched as a stunning red and black Magellanic woodpecker flew towards us and perched on the trunk of a nearby tree. -

Nature Colombia Trip Report - Eastern Andes & Mid-Magdalena´S Valley 2018

www.naturecolombia.com EASTERN ANDES & MID-MAGDALENA´S VALLEY 3rd March – 8th March 2018 Sword-billed Hummingbird (Ensifera ensifera) is characterized by its unusually long bill size; it is the only bird to have a beak longer than the length of its body. As all the pictures in this report, this picture was taken during this trip, in the Hummingbird Observatory Reserve - Bogotá. Nature Colombia Tour Leader: Roger Rodriguez Ardila 2 Nature Colombia Trip Report - Eastern Andes & Mid-Magdalena´s Valley 2018 Colombia is famed for its extraordinary diversity of birds. Thanks to its wide variety of landscapes and climates, Colombia is a megadiverse country with some of the highest biodiversity on the planet. Regardless of size, Colombia holds almost 20% of all birds in the planet (1,944 species, with new species still being discovered). Robert Holt, Lynne and I traveled together for 5 days, visiting some birding sites in the Eastern Andes and the Mid-Magdalena´s Valley looking for some endemic and special birds of this areas. In overall the trip was fast paced, designed to visit as much birding sites as we could of these two very different kind of environments. That also forced us to be in the car for long hours most of the days. We recorded 235 species (47 families), including 11 endemic bird species and 7 near-endemics. This was in spite of the complicated conditions mentioned before. Day Date Morning Afternoon Overnight Blue Suites Hotel - 1 03/03/18 Chingaza National Park Hummingbirds Observatory Bogotá 04/03/18 La Florida Park and El Enchanted Garden and transfer Rio Claro Reserve 2 Tabacal Lagoon to Rio Claro 3 05/03/18 Full day birding at Rio Claro Reserve Rio Claro Reserve 4 06/03/18 Rio Claro Reserve El Paujil Reserve El Paujil Reserve Blue Suites Hotel - 5 07/03/18 El Paujil Reserve Transfer to Bogotá Bogotá TOUR SUMMARY: Day 1. -

South Georgia & Antarctic Odyssey

South Georgia & Antarctic Odyssey 16 January – 02 February 2019 | Polar Pioneer About Us Aurora Expeditions embodies the spirit of adventure, travelling to some of the most wild and adventure and discovery. Our highly experienced expedition team of naturalists, historians and remote places on our planet. With over 27 years’ experience, our small group voyages allow for destination specialists are passionate and knowledgeable – they are the secret to a fulfilling a truly intimate experience with nature. and successful voyage. Our expeditions push the boundaries with flexible and innovative itineraries, exciting wildlife Whilst we are dedicated to providing a ‘trip of a lifetime’, we are also deeply committed to experiences and fascinating lectures. You’ll share your adventure with a group of like-minded education and preservation of the environment. Our aim is to travel respectfully, creating souls in a relaxed, casual atmosphere while making the most of every opportunity for lifelong ambassadors for the protection of our destinations. DAY 1 | Wednesday 16 January 2019 Ushuaia; Beagle Channel Position: 19:38 hours Course: 106° Wind Speed: 12 knots Barometer: 1006.6 hPa & steady Latitude: 54° 51’ S Speed: 12 knots Wind Direction: W Air Temp: 11°C Longitude: 68° 02’ W Sea Temp: 7°C The land was gone, all but a little streak, away off on the edge of the water, and We explored the decks, ventured down to the dining rooms for tea and coffee, then climbed down under us was just ocean, ocean, ocean—millions of miles of it, heaving up and down the various staircases. Howard then called us together to introduce the Aurora team and give a lifeboat and safety briefing. -

Of New Zealand Volume 31 Part 3 September 1984

NOTORNIS Journal of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand Volume 31 Part 3 September 1984 OFFICERS 1984 - 85 President - B. BROWN, 20 Redmount Place, Red Hill, Papakura Vice-president - R. B. SIBSON, 580 Remuera Road, Auckland 5 Editor - B. D. HEATHER, 10 Jocelyn Crescent, Silverstream Treasurer - D. F. BOOTH, P.O. Box 35337, Browns Bay, Auckland 10 Secretary - R. S. SLACK, c/o P.O., Pauatahanui, Wellington Council Members: SEN D. BELL, Zoology Dept, Victoria University, Private Bag, Wellington BRIAN D. BELL, 9 Ferry Road, Seatoun, Wellington P. C. BULL, 131A Waterloo Road, Lower Hutt D. E. CROCKETT, 21 McMilIan Avenue, Kamo, Whangarei P. D. GAZE, Ecology Division, DSIR, Private Bag, Nelson J. HAWKINS, 772 Atawhai Drive, Nelson P. M. SAGAR, 38A Yardley Street, Christchurch 4 Conveners and Organisers: Rare Birds Committee: Secretary, J. F. M. FENNELL, 224 Horndon Street, DarfieId, Canterbury Beach Patrol: R. G. POWLESLAND, Wildlife Service, Dept. of Internal Affairs, Private Bag, Wellington Librarian: A. 3. GOODWIN, R.D. 1, Clevedon Nest Records: D. E. CROCKETT Classified Summarised Notes - North Island: L. HOWELL, P.O. Box 57, Kaitaia South Island: P. D. GAZE, Ecology Division, DSIR, Private Bag, Nelson S.W. Pacific Islands Records: J. L. MOORE, 32 Brook St, Lower Hutt Assistant Editor: A. BLACKBURN, 10 Score Road, Gisborne Reviews Editor: D. H. BRATHWAITE, P.O. Box 31022 Ilam, Christchurch 4 Editor of OSNZ news: P. SAGAR, 38A Yardley St, Christchurch 4 SUBSCRIPTIONS AND MEMBERSHIP Annual Subscription: Ordinary member $20; Husband & wife mem- bers $30; Junior member (under 20) $15; Life Member $400; Family member (one Notornis per household) being other family of a member in the same household as a member $10; Institution $40; Overseas member and overseas institution $5.00 extra (postage). -

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

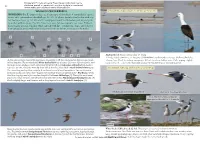

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 200 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard Pages xvii–xxiii: recent taxonomic changes, I have revised sev- Introduction to the Family Anatidae eral of the range maps to conform with more current information. For these updates I have Since the 978 publication of my Ducks, Geese relied largely on Kear (2005). and Swans of the World hundreds if not thou- Other important waterfowl books published sands of publications on the Anatidae have since 978 and covering the entire waterfowl appeared, making a comprehensive literature family include an identification guide to the supplement and text updating impossible. -

Bolivia 2007 © Birdfinders 2007

Bolivia 7–25 September 2007 Participants: Didier Godreau Rolf Gräfvert Helge Grastveit Andrew Self Dennis and Margaret Weir Leader: Nick Acheson and Leo Catari (driver) Yellow-tufted Woodpecker Day 1 Overnight flight from London via Miami. Day 2 Having arrived smoothly courtesy of American Airlines, we immediately set to work in the savannahs surrounding the Viru Viru airport. Here we were delighted to see Greater Rhea, Red-winged Tinamou, Campo Flicker and flocks of Blue-crowned Parakeets. After a fine lunch in Santa Cruz we headed for the Piraí River on the west side of the city, and the Urubó savannahs beyond it. Once we found a sheltered spot out of the wind we had great birding, seeing, among many others, Speckled Chachalaca, Yellow-tufted Woodpecker, Blue-winged Parrotlet, Green-cheeked Parakeet, Golden-collared and Chestnut-fronted Macaws, Chestnut-eared Aracari, Thrush-like Wren, and Greater Thornbird. A pair of Titi Monkeys was also popular here. Day 3 This morning was spent at the Jardín Botánico, ten kilometres east of the city of Santa Cruz. By the roadside we saw White Woodpecker and Red-crested Cardinal and around the pond we found a dozy Brown-throated Three- toed Sloth, Social and Rusty-margined Flycatchers (very thoughtfully perched next to each other for ease of comparison), Blue-crowned Trogon, Blue-crowned Motmot and Narrow-billed Woodcreeper. Highlights in the forest included Rufous Casiornis, White-wedged Piculet, White-crested Tyrannulet, Fawn-breasted Wren, Ferruginous Pygmy-owl and a family of Silvery Marmosets. This afternoon we drove to Los Volcanes where we were greeted by Andean Condor, Military Macaw, Channel-billed Toucan, Red-billed and Turquoise-fronted Parrots and noisy, sky-filling flocks of Mitred Parakeets. -

JOURNAL Number Six

THE JAMES CAIRD SOCIETY JOURNAL Number Six Antarctic Exploration Sir Ernest Shackleton MARCH 2012 1 Shackleton and a friend (Oliver Locker Lampson) in Cromer, c.1910. Image courtesy of Cromer Museum. 2 The James Caird Society Journal – Number Six March 2012 The Centennial season has arrived. Having celebrated Shackleton’s British Antarctic (Nimrod) Expedition, courtesy of the ‘Matrix Shackleton Centenary Expedition’, in 2008/9, we now turn our attention to the events of 1910/12. This was a period when 3 very extraordinary and ambitious men (Amundsen, Scott and Mawson) headed south, to a mixture of acclaim and tragedy. A little later (in 2014) we will be celebrating Sir Ernest’s ‘crowning glory’ –the Centenary of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic (Endurance) Expedition 1914/17. Shackleton failed in his main objective (to be the first to cross from one side of Antarctica to the other). He even failed to commence his land journey from the Weddell Sea coast to Ross Island. However, the rescue of his entire team from the ice and extreme cold (made possible by the remarkable voyage of the James Caird and the first crossing of South Georgia’s interior) was a remarkable feat and is the reason why most of us revere our polar hero and choose to be members of this Society. For all the alleged shenanigans between Scott and Shackleton, it would be a travesty if ‘Number Six’ failed to honour Captain Scott’s remarkable achievements - in particular, the important geographical and scientific work carried out on the Discovery and Terra Nova expeditions (1901-3 and 1910-12 respectively). -

The First Mangrove Swallow Recorded in the United States

The First Mangrove Swallow recorded in the United States INTRODUCTION tem with a one-lane unsurfaced road on top, Paul W. Sykes, Jr. The Space Coast Birding and Wildlife Festival make up the wetland part of the facility (Fig- USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center was held at Titusville, Brevard County, ures 1 and 2). The impoundments comprise a Florida on 13–17 November 2002. During total of 57 hectares (140 acres), are kept Warnell School of Forest Resources the birding competition on the last day of the flooded much of the time, and present an festival, the Canadian Team reported seeing open expanse of shallow water in an other- The University of Georgia several distant swallows at Brevard County’s wise xeric landscape. Patches of emergent South Central Regional Wastewater Treat- freshwater vegetation form mosaics across Athens, Georgia 30602-2152 ment Facility known as Viera Wetlands. open water within each impoundment and in They thought these were either Cliff the shallows along the dikes. A few trees and (email: [email protected]) (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota) or Cave (P. fulva) aquatic shrubs are scattered across these wet- Swallows. lands. Following his participation at the festival, At about 0830 EST on the 18th, Gardler Gardler looked for the swallows on 18 stopped on the southmost dike of Cell 1 Lyn S. Atherton November. The man-made Viera Wetlands (Figure 2) to observe swallows foraging low are well known for waders, waterfowl, rap- over the water and flying into the strong 1100 Pinellas Bayway, I-3 tors, shorebirds, and open-country passer- north-to-northwest wind. -

NB25-SLS-Schulenberg

>> SPLITS, LUMPS AND SHUFFLES Splits, lumps and shuffles Thomas S. Schulenberg This series focuses on recent taxonomic proposals – descriptions of new taxa, splits, lumps or reorganisations – that are likely to be of greatest interest to birders. This latest instalment includes: the possible lumps of Scale-breasted Woodpecker and South Georgia Pipit; a split in Red-billed Woodcreeper; a split in Highland Elaenia, and yet another possible lump in White-crested Elaenia; and a too-early-to-call-for-a-split-but-keep-an-eye-on-it study of Correndera Pipit. Sayonara, Scale-breasted There has been some grumbling over the years that a subspecies of Waved (amacurensis, of Woodpecker? northeastern Venezuela) perhaps belongs instead cale-breasted Woodpecker Celeus with Scale-breasted (Short 1982), and reports that grammicus and Waved Woodpecker C. not only were their vocalisations indistinguishable S undatus are two similar species that replace (Ridgely & Greenfield 2001), but even that each each other geographically, occupying respectively responded to playback of calls of the other (Restall the western and eastern portions of Amazonia. et al. 2006). Nonetheless the species status of the 2 1 3 Just lookalikes or the same species? 1 Scale-breasted Woodpecker Celeus grammicus, Iranduba, Amazonas, Brazil, September 2013 (Anselmo d’Affonseca); 2–3 Waved Woodpecker C. undatus, both Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil: 2 November 2011 (Anselmo d’Affonseca), 3 May 2017 (Tomaz Nascimento de Melo; 8 lattes.cnpq.br/0736734315806511). The absence of diagnostic vocal, plumage, or genetic differences between the two all seems to lead to the conclusion that there is one fewer species of woodpecker in the world.