(YTS) Services Final Evaluation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

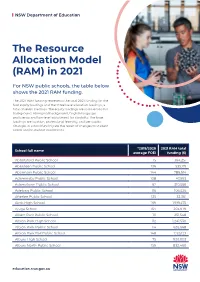

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 347,551 Alma Public -

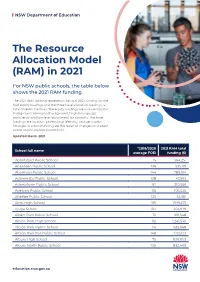

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. Updated March 2021 *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 -

NSWCHS - PUMA Football Cup & Trophy

The NSWCHS - PUMA Football Cup & Trophy 2018 Knock Out Football Team Information Est. 1889 NSWCHS ‐ PUMA Football Cup & Trophy . The PUMA Cup for boys . The PUMA Trophy for girls The Annual Knockout Football Competitions for New South Wales State High Schools RESULTS Results must be telephoned and/or emailed, by the winning school, to either the State KO Convener or to the respective Regional Convener, or the Sports High Co‐ordinator as indicated on the draw, immediately following the match. A written confirmation is to be forwarded within three school days. Failure to notify results may lead to the disqualification of the winning school. Your co‐operation is also sought in despatching the MEDIA/INTERNET REPORT to the Media Officer within TWO school days (Team photographs as jpg. attachments can also be forwarded). These will be publicised on the NSW Schools Football website. BOYS AND GIRLS FINAL SERIES DRAW 1. The draw for the Final Series will be conducted as a separate Statewide Regional ‐ Comprehensive High Schools Competition and Sports High School Competition with boys and girls divisions. 2. The 2018 PUMA Sports High School Football Competition will be played as a round robin & with a final for the 1st & 2nd positions, as indicated below: Please note the first mentioned team is the home team in all rounds. All other knockout home and away rules apply. Sports High School play by dates may vary to the PUMA Comprehensive High School schedule and played as gala days with each Sports High School hosting a round of competition. 2018 BOYS and GIRLS Sports High Schools DRAW: (i) Kick Off Times: Girls 10.00am Boys 11.30am (ii) The Home Team is the first mentioned team in the draw. -

Participating Schools List

PARTICIPATING SCHOOLS LIST current at Saturday 11 June 2016 School / Ensemble Suburb Post Code Albion Park High School Albion Park 2527 Albury High School* Albury 2640 Albury North Public School* Albury 2640 Albury Public School* Albury 2640 Alexandria Park Community School* Alexandria 2015 Annandale North Public School* Annandale 2038 Annandale Public School* Annandale 2038 Armidale City Public School Armidale 2350 Armidale High School* Armidale 2350 Arts Alive Combined Schools Choir Killarney Beacon Hill 2100 Arts Alive Combined Schools Choir Pennant Hills Pennant Hills 2120 Ashbury Public School Ashbury 2193 Ashfield Boys High School Ashfield 2131 Asquith Girls High School Asquith 2077 Avalon Public School Avalon Beach 2107 Balgowlah Heights Public School* Balgowlah 2093 Balgowlah North Public School Balgowlah North 2093 Balranald Central School Balranald 2715 Bangor Public School Bangor 2234 Banksmeadow Public School* Botany 2019 Bathurst Public School Bathurst 2795 Baulkham Hills North Public School Baulkham Hills 2153 Beacon Hill Public School* Beacon Hill 2100 Beckom Public School Beckom 2665 Bellevue Hill Public School Bellevue Hill 2023 Bemboka Public School Bemboka 2550 Ben Venue Public School Armidale 2350 Berinba Public School Yass 2582 Bexley North Public School* Bexley 2207 Bilgola Plateau Public School Bilgola Plateau 2107 Billabong High School* Culcairn 2660 Birchgrove Public School Balmain 2041 Blairmount Public School Blairmount 2559 Blakehurst High School Blakehurst 2221 Blaxland High School Blaxland 2774 Bletchington -

An Overview of Stile, Australia's #1 Science Resource Provider

An overview of Stile, Australia’s #1 science resource provider EXECUTIVE SUMMARY FOR SCHOOL LEADERS Stile | Executive summary for school leaders 2 Table of contents Welcome letter 3 How we are rethinking science education > Our principles 5 > Our pedagogy 7 > Our approach 9 A simple solution > Stile Classroom 12 > Squiz 14 > Professional learning 15 > Stile Concierge 16 Key benefits 17 The Stile community of schools 19 The rest is easy 24 Stile | Executive summary for school leaders 3 It’s time to rethink science at school I’m continuously awestruck by the sheer power of science. In a mere 500 years, a tiny fraction of humanity’s long history, science – and the technological advances that have stemmed from it – has completely transformed every part of our lives. The scale of humanity’s scientific transformation in such a short period is so immense it’s hard to grasp. My grandmother was alive when one of the world’s oldest airlines, Qantas, was born. In her lifetime, flight has become as routine as daily roll call. Disease, famine and the toll of manual labour that once ravaged the world’s population have also been dramatically reduced. Science is at the heart of this progress. Given such incredible advancement, it’s tempting to think that science education must be in pretty good shape. Sadly, it isn’t. We could talk about falling PISA rankings, or declining STEM enrolments. But instead, and perhaps more importantly, let’s consider the world to which our students will graduate. A world of “fake news” and “alternative facts”. -

Bossley Biz Newsletter

FOCUSSING ON EXCELLENCE & SUCCESS JUNE 2017 BOSSLEY BIZ NEWSLETTER #CaptureFairfield: Fairfield Mayor Frank Carbone with photography students at Bossley Park High School at the launch of council’s new photography competition. Picture: Simon Bennett Students attend the Sydney Writers Festival excursion BOSSLEY PARK HIGH SCHOOL FOCUSSING ON EXCELLENCE & SUCCESS JUNE 2017 FOCUSSING ON EXCELLENCE & SUCCESS JUNE 2017 Principal’s Message by Mrs Chevell (Principal) Head Teacher Special Education Congratulations to Ms Melinda Bournes, she has Refugee Expo been successful on merit to be appointed as our Head Teacher Special Education, following the – parents, cares and family members welcome. retirement of Mr Apps. This is a well-deserved promotion for Ms Bournes, who has been at the There are approximately 8,400 students from refugee backgrounds enrolled in NSW schools. Of this there are significant numbers in high schools in the school since the beginning of 2016. Fairfield and Liverpool areas. High schools in Fairfield and Liverpool have enrolled 3845 students with the possibility that there would be further increases in 2017/2018. In response to our refugee enrolments, Bossley Park High School will hold its inaugural; Refugee Expo on Friday 16th June from Congratulations to 9am-1:30pm for parents in the MPC Andrea Agamemnonos Recently at the Sydney FC awards night, Year 12 The purpose of the day is to deliver information that is relevant to our newly student 2016, Andrea Agamemnonos was named, our arrived parents including, pathway options for students, English classes the Sydney FC, ‘Youth League Players’ Player for parents, legal advice and access to local support groups. -

Nsw Government Schools Capacity Update De International

NSW GOVERNMENT SCHOOLS DE INTERNATIONAL NSW GOVERNMENT SCHOOLS CAPACITY UPDATE Please note that the information provided below is correct to the best of our knowledge as of 14 March 2019, based on information received from NSW government schools. Individual school requirements are listed under each school. School located in Sydney that are not listed are either full or ineligible to enrol international students. Schools located outside of Greater Sydney and Wollongong are classified as regional schools. No capacity update is available for primary schools due to their large number and strict catchment areas. For enrolments into a NSW government primary school please contact a DE International staff member with a NSW address or location. School catchment areas can be found at https://education.nsw.gov.au/school-finder. There is no guarantee of placement at schools listed below. Please do not guarantee placement at any school to prospective students. Region School 2019 2020 Inner Western Sydney Alexandria Park Community School Capacity in all year levels Capacity in all year levels Western Sydney Arthur Phillip High School Capacity in Years 7-10 Capacity in all year levels Must commence Year 11 in Term 1 Northern Sydney Asquith Boys High School Capacity in Years 9-11 Capacity in all year levels Northern Sydney Asquith Girls High School Capacity in all year levels Capacity in all year levels South Western Sydney Bankstown Girls High School Capacity in all year levels Capacity in all year levels South Western Sydney Bankstown Senior College -

Bossley Biz Newsletter

FOCUSSING ON EXCELLENCE & SUCCESS MAY 2017 BOSSLEY BIZ NEWSLETTER Athletics Carnival School Dance Ensemble (Anzac Day Ceremony) BOSSLEY PARK HIGH SCHOOL FOCUSSING ON EXCELLENCE & SUCCESS MAY 2017 Principal’s Message Dear Parents and Carers Bossley Park High School will transition to the new NSW public schools’ finance system and a new bank account on 24 July 2017. To ensure a smooth transition, there will be changes to the way we accept parent or carer payments. 1. Direct deposits: As of 30 June 2017, we will no longer accept direct deposits into our current school bank account as we prepare to close this account and transition to the new one. Any payments made using direct deposit after this date cannot be properly allocated to a student’s account in a timely manner. Please ensure you have made any outstanding direct deposits before 30 June 2017. 2. EFTPOS payments: We will not be able to accept EFTPOS payments between 19 July and 24 July 2017. Please ensure that you have made any outstanding EFTPOS payments before 19 July 2017. From 25 July 2017, EFTPOS payments will be accepted as before. 3. Cash and cheque payments: Between 19 July 2017 and 24 July 2017, we will also not be able to accept payments by cash or cheque as we prepare to close our current bank account and transition to the new one. Please ensure that you have made any outstanding cash or cheque payments before 19 July 2017. From 25 July 2017, cash and cheque payments will be accepted as before. Thank you for your patience and understanding as we transition to our new finance system. -

Year in Review 2019-2020 Online

YEAR IN REVIEW 2019/20 Contents 04 Chairman’s Message 05 CEO’s Message 06 Blacktown Venue Management Ltd 07 Blacktown Venue Management Ltd Board of Directors 08 Blacktown Key Venues 09 Blacktown Key Venues Management Sta 10 Health & Safety 12 2019/2020 Highlights 14 Blacktown Football Park 16 Blacktown International Sportspark Sydney 18 AFL 20 Athletics Centre 22 Baseball 24 Cricket 26 Football 28 Soball 30 Joe McAleer Oval 32 Rooty Hill Leisure Centre 34 Blacktown Tennis Centre Stanhope 36 Blacktown Aquatic Centre 38 Blacktown Leisure Centre Stanhope 40 Charlie Lowles Leisure Centre Emerton 43 Mount Drui Swimming Centre 44 Riverstone Swimming Centre 46 Aqua Learn to Swim 48 Looking forward 50 List of hirers 2 3 Chairman’s message CEO’s message As I look back at my inaugural year as Chairman of The ¡rst half of 2020 also brought tragedy to our door. In It would be remiss of me not to start this message without The development of the BISP International Centre of Blacktown Venue Management Ltd (BVM) I am honoured late March we lost a valued colleague from Charlie Lowles recognising the tremendous group of people I have Excellence (ICTE) continues to evolve and I was pleased to to have led the BVM Board over the past year. Leisure Centre Emerton, Ms Dani Gordon, in a tragic the honour of working alongside. The dreadful bush¡re welcome Dr Neil Gibson as the new Director of the ICTE. In accident. Dani’s loss impacted all at BVM, Key Venues season that befell the country during the summer months partnership with the Australian Catholic Universities (ACU), As a Board we are proud to be the custodians of facilities and throughout our wider Blacktown City Council family. -

School by School Gonski Funding - Nsw

SCHOOL NAME EXTRA GONSKI SCHOOL NAME EXTRA GONSKI FUNDING 2014-2019 FUNDING 2014-2019 Abbotsford Public School 1,612,519 Albury West Public School 573,867 Aberdeen Public School 1,316,465 Aldavilla Public School 1,349,506 Abermain Public School 1,178,643 Alexandria Park Community School 1,543,635 Adaminaby Public School 144,056 Alfords Point Public School 912,773 Adamstown Public School 1,058,811 Allambie Heights Public School 1,929,286 Adelong Public School 578,221 Alma Public School 1,041,617 Afterlee Public School 119,763 Alstonville High School 4,252,381 Airds High School 1,772,563 Alstonville Public School 2,592,818 Ajuga School 544,319 Ambarvale High School 4,870,365 Albert Park Public School 338,570 Ambarvale Public School 1,011,935 Albion Park High School 5,356,594 Ando Public School 86,365 Albion Park Public School 2,442,013 Anna Bay Public School 1,970,918 Albion Park Rail Public School 1,549,113 Annandale North Public School 1,756,022 Albury High School 5,308,203 Annandale Public School 974,333 Albury North Public School 1,034,901 Annangrove Public School 297,579 Albury Public School 2,454,674 Anson Street School 1,080,061 SCHOOL BY SCHOOL GONSKI FUNDING - NSW SCHOOL NAME EXTRA GONSKI SCHOOL NAME EXTRA GONSKI FUNDING 2014-2019 FUNDING 2014-2019 Appin Public School 1,014,139 Ashcroft Public School 1,113,386 Arcadia Public School 429,488 Ashfield Boys High School 3,062,576 Arcadia Vale Public School 639,049 Ashfield Public School 834,018 Ardlethan Central School 622,411 Ashford Central School 879,197 Argenton Public School 281,881 -

Featured Dancers

2016 SCHOOLS SPECTACULAR FEATURED DANCERS Sharmaine Amurao Endeavour Sports High School Kristina Atsiaris Randwick Girls High School Erika Blendell Northern Beaches Secondary College Mackellar Girls Campus Georgia Bone Port Hacking High School Jaslyn Boughton Northern Beaches Secondary College Mackellar Girls Campus Molly Bugeja Nepean Creative and Performing Arts High School Connie Bunting Nepean Creative and Performing Arts High School Rochene Cassidy Nepean Creative and Performing Arts High School Benjamin Clay Kirrawee High School Jannali Craigie Maitland High School Ebony Cunliffe Newtown High School of the Performing Arts Bree De Carli Newtown High School of the Performing Arts Cameron Doherty Northmead Creative and Performing Arts High School Kayla El-Said Casula High School Nofiah El-Said Casula High School Francesca Fenton The Henry Lawson High School Talia Ferchow Engadine High School Brittany Ford Nepean Creative and Performing Arts High School Cameron Gaw Northern Beaches Secondary College Mackellar Girls Campus Sophia Govas Newtown High School of the Performing Arts Natalie Gow Nepean Creative and Performing Arts High School Katie Haldane Wollongong High School of the Performing Arts Jordan Hemphill Karabar High School Jarrod Herrmann Kirrawee High School Gabi Hong Strathfield Girls High School Joanne Hwang Newtown High School of the Performing Arts Natassija-Belle James Newtown High School of the Performing Arts Emmeline Judge Campbelltown Performing Arts High School Ellie Kennedy Nepean Creative and Performing Arts High -

Annual Report 2017– 18 Whatwe Do

Annual Report 2017– 18 Whatwe do Our student scholarships address factors contributing to Support students who disadvantage: face social and economic disadvantage to achieve Students from low their full potential socio-economic through life-changing backgrounds scholarships. Indigenous students Provide professional Students from refugee development opportunities backgrounds to educators and school leaders to enable them to Students in rural and extend their leadership remote areas and teaching skills. Students living with a disability Enhance the value and reputation of Australia’s The Public Education Foundation is committed public schools, ensuring to helping break the every Australian has cycle of educational disadvantage and reducing access to a high-quality, inequality by supporting students and educators inclusive education. in Australia’s public education system. 2 PUBLIC EDUCATION FOUNDATION Contents Our Impact 2 Chair Report 3 Executive Director Report 4 Proudly Public Awards Night 5 2018 Public Education Foundation Scholarship Recipients 6 2017 Minister’s and Secretary’s Awards for Excellence 10 Scholar profiles 12 The Public Education Foundation Advocacy and Research 14 is a charity dedicated to providing life-changing scholarships to young people in Our People 15 public education, their teachers and principals. 2017-18 Financial Report 16 The Foundation is supported Board of Directors 20 by the NSW Department of Education and works in Donors & Supporters 21 collaboration with schools, communities, the private sector and the