Japanese Paper: History, Development and Use in Western Paper Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making! the E-Magazine for the Fibrous Forest Products Sector

PAPERmaking! The e-magazine for the Fibrous Forest Products Sector Produced by: The Paper Industry Technical Association Volume 5 / Number 1 / 2019 PAPERmaking! FROM THE PUBLISHERS OF PAPER TECHNOLOGY Volume 5, Number 1, 2019 CONTENTS: FEATURE ARTICLES: 1. Wastewater: Modelling control of an anaerobic reactor 2. Biobleaching: Enzyme bleaching of wood pulp 3. Novel Coatings: Using solutions of cellulose for coating purposes 4. Warehouse Design: Optimising design by using Augmented Reality technology 5. Analysis: Flow cytometry for analysis of polyelectrolyte complexes 6. Wood Panel: Explosion severity caused by wood dust 7. Agriwaste: Soda-AQ pulping of agriwaste in Sudan 8. New Ideas: 5 tips to help nurture new ideas 9. Driving: Driving in wet weather - problems caused by Spring showers 10. Women and Leadership: Importance of mentoring and sponsoring to leaders 11. Networking: 8 networking skills required by professionals 12. Time Management: 101 tips to boost everyday productivity 13. Report Writing: An introduction to report writing skills SUPPLIERS NEWS SECTION: Products & Services: Section 1 – PITA Corporate Members: ABB / ARCHROMA / JARSHIRE / VALMET Section 2 – Other Suppliers Materials Handling / Safety / Testing & Analysis / Miscellaneous DATA COMPILATION: Installations: Overview of equipment orders and installations since November 2018 Research Articles: Recent peer-reviewed articles from the technical paper press Technical Abstracts: Recent peer-reviewed articles from the general scientific press Events: Information on forthcoming national and international events and courses The Paper Industry Technical Association (PITA) is an independent organisation which operates for the general benefit of its members – both individual and corporate – dedicated to promoting and improving the technical and scientific knowledge of those working in the UK pulp and paper industry. -

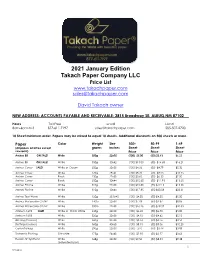

2021 January Edition Takach Paper Company LLC Price List [email protected]

2021 January Edition Takach Paper Company LLC Price List www.takachpaper.com [email protected] David Takach owner NEW ADDRESS: ACCOUNTS PAYABLE AND RECEIVABLE: 2815 Broadway SE. ALBUQ.NM 87102 Hours Toll Free email Local 8am-6pm M-S 877-611-7197 [email protected] 505-507-2720 10 Sheet minimum order. Papers may be mixed to equal 10 sheets. Additional discounts on 500 sheets or more. Paper Color Weight Size 100+ 50-99 1-49 (All papers acid free except grams inches Sheet Sheet Sheet newsprint) Price Price Price Arches 88 ON SALE! White 300g 22x30 (100) $5.00 (50) $5.63 $6.25 Arches 88 ON SALE! White 350g 30x42 (100) $13.05 (50) $14.68 $16.21 Arches Cover SALE! White or Cream 250g 22x30 (100) $4.26 (50) $4.79 $5.32 Arches Cover White 270g 29x41 (100) $8.20 (50) $9.23 $10.25 Arches Cover Black 250g 22x30 (100) $5.60 (50) $6.30 $7.00 Arches Cover Black 250g 30x44 (100) $10.60 (50) $11.93 $13.25 Arches Platine White 310g 22x30 (100) $10.80 (25) $12.15 $13.50 Arches Platine White 310g 30x44 (100) $17.85 (25) $20.08 $22.31 Arches Text Wove White 120g 25.5x40 (100) $4.00 (50) $4.50 $5.00 Arches Watercolor CP/HP White 140lb 22x30 (100) $7.08 (50) $7.87 $8.85 Arches Watercolor CP/HP White 300lb 22x30 (100) $16.26 (50) $18.07 $20.33 Arnhem 1618 SALE! White or Warm White 245g 22x30 (100) $2.40 (50) $2.70 $3.00 Arnhem 1618 White 320g 22x30 (100) $4.10 (50) $4.62 $5.13 Blotting (cosmos) White 360g 24x38 (100) $3.16 (50) $3.76 $3.50 Blotting (cosmos) White 360g 40x60 (100) $8.15 (50) $9.06 $10.20 Coventry Rag White 290g 22x30 (100) 3.10 (50) $3.44 -

2019 Catalog 12-14.Pdf

www.legionpaper.com www.moabpaper.com www.risingmuseumboard.com www.solvart.com © Copyright 2019 Legion Paper Corporation All Rights Reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced without the permission of Legion Paper. OUR ROMANCE WITH PAPER Peace treaties are signed on it. Declarations of love are written on it. Artists’ works are portrayed on it. Of course, we mean paper; the medium that has evolved to reflect its own poetry, becoming an opportunity for pure innovation and unlimited creativity. Through the years, a melding of ancient craft and enlightened technology occurred, creating new practices and opening new horizons for expression in paper. When we trace its history, we find insight into man’s relentless imagination and creativity. Today, this convergence of ancient and modern continues and paper emerges with not only greater variety but a renewed appreciation of quality. To some, fine paper is the space that translates what is conceived in the mind to what is authentic. To others, having access to the right paper represents abundant possibility and profitability. The very selection of paper now becomes an adventure, realizing how the end result will vary based upon choice. Today, as in the years past, Legion Paper continues to source the finest papermakers around the globe, respecting the skill of the artisan and the unique attributes of the finished product. As we head into the future, Legion remains steadfast in its commitment to diversity, customer service and an unparalleled level of professionalism. We’re sure you will want to touch and feel some of the 3,500 papers described on the following pages. -

Museum of Economic Botany, Kew. Specimens Distributed 1901 - 1990

Museum of Economic Botany, Kew. Specimens distributed 1901 - 1990 Page 1 - https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/57407494 15 July 1901 Dr T Johnson FLS, Science and Art Museum, Dublin Two cases containing the following:- Ackd 20.7.01 1. Wood of Chloroxylon swietenia, Godaveri (2 pieces) Paris Exibition 1900 2. Wood of Chloroxylon swietenia, Godaveri (2 pieces) Paris Exibition 1900 3. Wood of Melia indica, Anantapur, Paris Exhibition 1900 4. Wood of Anogeissus acuminata, Ganjam, Paris Exhibition 1900 5. Wood of Xylia dolabriformis, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 6. Wood of Pterocarpus Marsupium, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 7. Wood of Lagerstremia parviflora, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 8. Wood of Anogeissus latifolia , Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 9. Wood of Gyrocarpus jacquini, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 10. Wood of Acrocarpus fraxinifolium, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 11. Wood of Ulmus integrifolia, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 12. Wood of Phyllanthus emblica, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 13. Wood of Adina cordifolia, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 14. Wood of Melia indica, Anantapur, Paris Exhibition 1900 15. Wood of Cedrela toona, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 16. Wood of Premna bengalensis, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 17. Wood of Artocarpus chaplasha, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 18. Wood of Artocarpus integrifolia, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 19. Wood of Ulmus wallichiana, N. India, Paris Exhibition 1900 20. Wood of Diospyros kurzii , India, Paris Exhibition 1900 21. Wood of Hardwickia binata, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 22. Flowers of Heterotheca inuloides, Mexico, Paris Exhibition 1900 23. Leaves of Datura Stramonium, Paris Exhibition 1900 24. Plant of Mentha viridis, Paris Exhibition 1900 25. Plant of Monsonia ovata, S. -

C:\Data\WP\F\200\Catalogue Sections\Aaapreliminary Pages.Wpd

Jonathan A. Hill, Bookseller, Inc. 325 West End Avenue, Apt. 10B New York City, New York, 10023-8145 Tel: 646 827-0724 Fax: 212 496-9182 E-mail: [email protected] Catalogue 200 Proofs Science, Medicine, Natural History, Bibliography, & Much More Introduction & Selective Subject Index on Following Pages Introduction TWO HUNDRED CATALOGUES in thirty-three years: more than 35,000 books and manuscripts have been described in these catalogues. Thousands of other books, including many of the most important and unusual, never found their way into my catalogues, having been quickly sold before their descriptions could appear in print. In the last fifteen years, since my Catalogue 100 appeared, many truly exceptional books passed through my hands. Of these, I would like to mention three. The first, sold in 2003 was a copy of the first edition in Latin of the Columbus Letter of 1493. This is now in a private collection. In 2004, I was offered a book which I scarcely dreamed of owning: the Narratio Prima of Rheticus, printed in 1540. Presenting the first announcement of the heliocentric system of Copernicus, this copy in now in the Linda Hall Library in Kansas City, Missouri. Both of the books were sold before they could appear in my catalogues. Finally, the third book is an absolutely miraculous uncut copy in the original limp board wallet binding of Galileo’s Sidereus Nuncius of 1610. Appearing in my Catalogue 178, this copy was acquired by the Library of Congress. This is the first and, probably the last, “personal” catalogue I will prepare. -

Preferred Source Application Requests

PREFERRED SOURCE APPLICATIONS APPROVED BY OGS AUGUST 2010 THROUGH OCTOBER 2010 Total Total OGS PSG Direct Disabled/ ESD Request Annual Sales Labor Blind Approval Control Number Commodity Type Customer Volume Workshop FTE's FTE's Date 823 Personal Protection Spray New Statewide $40,398.00 Herkimer Area ARC .07 .07 8/23/10 828 HIV Rapid Test Kits New Statewide $200,000.00 Maryhaven Center of Hope .447 .383 8/5/10 Diesel Exhaust Fluid 832 275 and 330 gallon tote New Statewide $200,000.00 Liberty Enterprises Inc .2345 .1759 9/29/10 Diesel Exhaust Fluid 833 55 gallon drum New Statewide $30,000.00 Liberty Enterprises Inc .1614 .1210 9/29/10 835 Thermal Paper Rolls New Statewide $84,000.00 ARC Oneida Lewis .1097 .1036 10/8/10 Description for My®Clyns Personal Protection Spray My®Clyns Personal Protection Spray represents a new category of product that is intended to be used following exposure to bodily fluids or other materials potentially containing harmful pathogens. It is the only non-alcohol option you can keep in your pocket and spray directly into your face, eyes, ears, nose, mouth and open wounds. It is ready to use in the field when you need effective protection right away. This commodity is provided by Herkimer Area ARC and will be available to all State Agencies. Work for the disabled includes receiving packaging, removing individual units and transferring to an assembly line, assemble shipping box, fill box with 12 units, close box and tape shut, apply shipping label and load pallet with finished product. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 369 2nd International Conference on Humanities Education and Social Sciences (ICHESS 2019) Research on Design Strategy of Handmade Paper Products under the Concept of Cultural Consumption Shuyi Li1,a, Zhou Zhong2,b,*, Xiaopeng Peng3,c 1,2Guangdong University of Technology, Guangzhou 510090, China 3Zhongkai College of Agricultural Engineering, Guangzhou 510225, China [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] *Corresponding author Keywords: handmade paper, product design, cultural consumption, cultural heritage. Abstract. Handmade paper products are the carrier of disseminating folk culture. This article puts the design of handmade paper products under the context of cultural consumption concept, integrates modern design ideas, deeply analyzes market demand, and explores new ideas of product design.In the trend of cultural consumption, designers must dig deeply into the artistic characteristics of handmade paper, so that their products can be recognized by the society, establish cultural brands and integrate into the cultural life of the public. The design of handmade paper products needs emotional experience to get people's cultural resonance, and needs to guide people to better understand the cultural spirit behind handmade paper, so as to better inherit and develop traditional culture. 1. Introduction Traditional Chinese Arts and Crafts has a long history, among which the folk papermaking occupies an important historical position. The appearance of handmade paper can be traced back to the Western Han Dynasty. Later, after the improvement of Cai Lun of the Eastern Han Dynasty, a relatively stable papermaking method was formed. With the development of the times, the emergence of mechanization has changed the production mode of paper. -

Hands-On Explorations of Plane Transformations

Hands-On Explorations of Plane Transformations James King University of Washington Department of Mathematics [email protected] http://www.math.washington.edu/~king The “Plan” • In this session, we will explore exploring. • We have a big math toolkit of transformations to think about. • We have some physical objects that can serve as a hands- on toolkit. • We have geometry relationships to think about. • So we will try out at many combinations as we can to get an idea of how they work out as a real-world experience. • I expect that we will get some new ideas from each other as we try out different tools for various purposes. Our Transformational Case of Characters • Line Reflection • Point Reflection (a rotation) • Translation • Rotation • Dilation • Compositions of any of the above Our Physical Toolkit • Patty paper • Semi-reflective plastic mirrors • Graph paper • Ruled paper • Card Stock • Dot paper • Scissors, rulers, protractors Reflecting a point • As a first task, we will try out tools for line reflection of a point A to a point B. Then reflecting a shape. A • Suggest that you try the semi-reflective mirrors and the patty paper for folding and tracing. Also, graph paper is an option. Also, regular paper and cut-outs M • Note that pencils and overhead pens work on patty paper but not ballpoints. Also not that overhead dots are easier to see with the mirrors. B • Can we (or your students) conclude from your C tool that the mirror line is the perpendicular bisector of AB? Which tools best let you draw this reflection? • When reflecting shapes, consider how to reflect some polygon when it is not all on one side of the mirror line. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 124 International Conference on Contemporary Education, Social Sciences and Humanities (ICCESSH 2017) Inheritance and Industrial Development of Traditional Handcraft Paper Making Process in Beizhang Village, Chang’an Shaanxi Yuan Shao School of Fine Arts Shaanxi Normal University Xi’an, China Abstract—China’s paper making technique has been transmitted to other countries in Asia, Africa, Europe and leading around the world, which has witnessed the America, reaching every corner around the world. development of over two-thousand years since Han and Tang dynasties. The handcraft paper making process in Beizhang II. PAPER MAKING IN BEIZHANG VILLAGE, CHANG’AN Village, Changan, Shaanxi, a remains of the ancient paper making, is in a trend of being forgotten during the evolvement of historic culture and economic development. For the A. Historic Source of Paper Making in Beizhang Village intangible cultural heritages which are gradually disappearing North regions are sources of handcraft paper making in in China, the optimal method to inherit is to industrialize. China, which were cores of paper making in history and Based on the status quo and paper making process in Beizhang replaced by south regions in Song and Yuan dynasties. Village, the article compares the paper making industries Beizhang Village, Chang’an District, Xi’an, Shaanxi between the region and other regions in the country and raises Province is located at Xinglong Town, Chang’an District, at feasible suggestions for the industrialization of handcraft the foot of Qinling Mountains. The paper making records in paper making in Shaanxi. The industrialized development is Beizhang Village can be traced back to East Han Dynasty, expected to improve the understanding of the public to the which can be seen from the remains of Baqiao paper, till handcraft paper making, expand the publicity and increase the now, there is a ballad about paper making by Cai Lun economic benefits so as to continue the handcraft paper spreading in Beizhang Village. -

Portada Tesis Copia.Psd

EL PAPEL EN EL GEIDŌ Enseñanza, praxis y creación desde la mirada de Oriente TESIS DOCTORAL María Carolina Larrea Jorquera Directora: Dra. Marina Pastor Aguilar UNIVERSITAT POLITÈCNICA DE VALÈNCIA FACULTAT DE BELLES ARTS DE SANT CARLES DOCTORADO EN ARTE: PRODUCCIÓN E INVESTIGACIÓN Valencia, Junio 2015 2 A mis cuchisobrinos: Mi dulce Pablo, mi Fruni Fru, Emilia cuchi y a Ema pomonita. 3 4 Agradecimientos Mi más sincera gratitud a quienes a lo largo de estos años me han apoyado, aguantado y tendido una mano de diferentes maneras en el desarrollo y conclusión de esta tesis. Primero agradecer a mi profesor y mentor Timothy Barrett, por enseñarme con tanta generosidad el oficio y arte del papel tradicional hecho a mano japonés y europeo, y por compartir sus experiencias como aprendiz en nuestros trayectos hacia Oakdale. A Claudia Lira por hablarme del camino, a Sukey Hughes por compartir sus vivencias como aprendiz y su percepción del oficio, a Hiroko Karuno por mostrarme con dedicación el arte del shifu, a Paul Denhoed y Maki Yamashita por guiarme y recibirme amablemente en su casa, a Rina Aoki por su buen humor, hospitalidad y amistad, a Lauren Pearlman por socorrerme en el idioma japonés, a Clara Ruiz por abrirme las puertas de su casa, por su amistad y buena cocina, a Nati Garrido por ayudarme a cuidar de mi salud y que no me falte el deporte, a Miguel A. por llenarme el corazón de sonrisas y lágrimas que valen la pena atesorar, Clara Castillo, Alfredo Llorens y Ana Sánchez Montabes, por su amistad y cariño, a José Borge por enseñarme que Word tiene muchas más herramientas, a Marina Pastor por sus consejos en la mejor manera de mostrar la información, a mi familia y a mis amigos chilenos y valencianos que con su buena energía me han dado mucha fuerza para terminar este trabajo. -

Wryly Noted-Books About Books John D

Against the Grain Volume 29 | Issue 6 Article 22 December 2017 Wryly Noted-Books About Books John D. Riley Gabriel Books, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/atg Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Riley, John D. (2017) "Wryly Noted-Books About Books," Against the Grain: Vol. 29: Iss. 6, Article 22. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7771/2380-176X.7886 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Wryly Noted — Books About Books Column Editor: John D. Riley (Against the Grain Contributor and Owner, Gabriel Books) <[email protected]> https://www.facebook.com/Gabriel-Books-121098841238921/ Paper: Paging Through History by Mark Kurlansky. (ISBN: 978-0-393-23961-4, thanks to the development of an ingenious W. W. Norton, New York 2016.) device: a water-powered drop hammer.” An- other Fabriano invention was the wire mold for laying paper. “Fine wire mesh laid paper came his book is not only a history of paper, ample room to wander into Aztec paper making to define European paper. Another pivotal but equally, of written language, draw- or artisan one vat fine paper making in Japan. innovation in Fabriano was the watermark. Ting, and printing. It is about the cultural Another trademark of Kurlansky’s is a Now the paper maker could ‘sign’ his work.” and historical impact of paper and how it has pointed sense of humor. When some groups The smell from paper mills has always been central to our history for thousands of advocated switching to more electronic formats been pungent, due to the use of old, dirty rags years. -

Title Historical Value of Parabaik and Pei All Authors Moe Moe Oo Publication Type Local Publication Publisher (Journal Name, Is

Title Historical Value of Parabaik and Pei All Authors Moe Moe Oo Publication Type Local Publication Publisher (Journal name, Meiktila University, Research Journal, Vol.IV, No.1, 2013 issue no., page no etc.) Parabaiks and Palm Leaf Manuscripts are important in the rich and old tradition and cultural history of Southeast Asia. Many documents reflected the socio- economic situation and Buddhist text of ancient Myanmar. These sources are Abstract like a treasure-trove for historians. We hope that this Parabaik and Palm leaf will advance the study of the early modern history of Myanmar, as well as that of the whole Southeast Asian region, and will also contribute to the preservation of a valuable cultural heritage in Myanmar. cultural heritage, preservation Keywords Citation Issue Date 2013 61 Meiktila University, Research Journal, Vol.IV, No.1, 2013 Historical Value of Parabaik and Pei Moe Moe Oo1 Abstract Parabaiks and Palm Leaf Manuscripts are important in the rich and old tradition and cultural history of Southeast Asia. Many documents reflected the socio-economic situation and Buddhist text of ancient Myanmar. These sources are like a treasure-trove for historians. We hope that this Parabaik and Palm leaf will advance the study of the early modern history of Myanmar, as well as that of the whole Southeast Asian region, and will also contribute to the preservation of a valuable cultural heritage in Myanmar. Key Words: cultural heritage, preservation Introduction Myanmar Manuscripts are an attempt to deal with the socio- economic life of the people during the Kon-baung period. There are many books both published and unpublished in the forms of research journal and thesis.