First Nation Consultation Framework

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unification of Naasquuisaqs and Tlâ•Žaakwakumlth

International Textile and Apparel Association 2018: Re-Imagine the Re-Newable (ITAA) Annual Conference Proceedings Jan 1st, 12:00 AM Unification of Naasquuisaqs and Tl’aakwakumlth Denise Nicole Green Cornell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/itaa_proceedings Part of the Fashion Design Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, and the Indigenous Studies Commons Green, Denise Nicole, "Unification of Naasquuisaqs and Tl’aakwakumlth" (2018). International Textile and Apparel Association (ITAA) Annual Conference Proceedings. 67. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/itaa_proceedings/2018/design/67 This Design is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Symposia at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Textile and Apparel Association (ITAA) Annual Conference Proceedings by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ! ! Cleveland, Ohio 2018! Proceedings ! ! Title: Unification of Naasquuisaqs and Tl’aakwakumlth Designers: Denise Nicole Green, Cornell University & Haa’yuups (Ron Hamilton), Hupacasath First Nation Keywords: Native American, Hupacasath, Nuu-chah-nulth, Indigenous Fashion Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations hail from the West coast of Vancouver Island and are a confederacy of 14 smaller sovereign nations. According to their traditional beliefs, they have occupied these territories since iikmuut (the time before time) and archaeological evidence from this region confirms occupation for at least 5000 years (McMillan 2000). Like other Northwest Coast indigenous peoples, Nuu-chah-nulth social organization is complex and reflected in design practice and iconography (Holm 2014; Jonaitis 2006). Families own crests, which are iconographic imagery that represent histories, rights, and privileges (Green 2014). -

Building Bridges Together

building bridges together a resource guide for intercultural work between aboriginal and non-aboriginal peoples may 2008 this resource guide consists of discussions and stories about key concepts and historical developments that inform current-day intercultural work between aboriginal and non-aboriginal peoples in bc. by reading this resource guide, you will: gain an awareness of the diverse perspectives inherent to intercultural work between aboriginal and non-aboriginal peoples in bc acquire information about online and text resources that relate to intercultural work between aboriginal and non-aboriginal peoples in bc building bridges together a resource guide for intercultural work between aboriginal and non-aboriginal peoples lead author & editor scott graham contributors crystal reeves, paulette regan, brenda ireland, eric ostrowidzki, greg george, verna miller, ellie parks and laureen whyte design & layout joanne cheung & matthew beall cover artwork kinwa bluesky prepared by the social planning and research council of british columbia special thanks to the vancouver foundation for their generous support for this project © MAY 2008 library & archives canada cataloguing in publication graham, scott, 1977 – building bridges together: a resource guide for intercultural work between aboriginal and non aboriginal peoples includes bibliogrpahical references. also available in electronic format. ISBN 978-0-9809157-3-0 SOCIAL PLANNING AND RESEARCH COUNCIL OF BC 201-221 EAST 10TH AVE. VANCOUVER, BC V5T 4V3 WWW.SPARC.BC.CA [email protected] TEL: 604-718-7733 building bridges together a resource guide for intercultural work between aboriginal and non-aborignial peoples acknowledgements: the content of the building bridges together series would not be possible without the insightful contributions of the members of the building bridges together advisory committee. -

Best Practices for Consultation and Accommodation

Best Practices for Consultation and Accommodation Prepared for: New Relationship Trust Prepared by: Meyers Norris Penny LLP September 2009 Table of Contents Best Practices for Consultation and Accommodation................................................................................... i Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................................iii Summary of Best Practices for First Nations in Consultation and Accommodation .......................... iv 1. Introduction ...............................................................................................................................................1 1. 1 Project Vision and Purpose .........................................................................................................1 1.2 How to Use this Guide.................................................................................................................1 1.3 What are Best Practices? ............................................................................................................3 1.4 What is the Duty to Consult...........................................................................................................4 Aboriginal Rights & Title..............................................................................................................4 Duty to Consult and Accommodate ............................................................................................4 Who?...........................................................................................................................................5 -

Reconciling Aboriginal Rights with International Trade Agreements: Hupacasath First Nation V

Reconciling Aboriginal Rights with International Trade Agreements: Hupacasath First Nation v. Canada Kathryn Tucker* 1. BACKGROUND 111 1.1 duty to Consult and Accomodate 111 1.2 Bilateral Investment Agreement 113 1.3 Hupacasath First Nation 115 2. FACTS OF CASE AND DECISION 116 2.1 Grounds of the application 116 2.2 Application of Three-Part Test 116 2.2.1 SIGNIFICANT CHANGE IN LEGAL FRAMEWORK 117 2.2.2 SCOPE OF SELF-GOVERNMENT 120 3. COMMENTARY 121 3.1 Speculative and No Causal Link 121 3.1.1 HIGH-LEVEL MANAGEMENT DECISION 121 3.1.2 MST, MFN, AND EXPROPRIATION PROVISIONS 123 3.1.3 CHILLING EFFECT 123 3.2 Modern First Nations’ Agreements 124 3.3 Environmental Assessment of CCFIPPA 125 3.4 Aboriginal Self-Governance 127 3.5 Circumstances of Applicant 127 4. CONCLUSION 128 * Associate at Hutchins Legal Inc., practicing in the fields of Aboriginal and environmental law. The author is a member of the Barreau du Quebec and the Law Society of Upper Canada. She has an LL.M. in environ- mental law from Vermont Law School, and an LL.B. and B.C.L. from McGill University. Special thanks to Peter Hutchins for continuing to share his knowledge of and enthusiasm for Aboriginal law. 110 JSDLP - RDPDD Tucker ith the introduction of section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982,1 Canada recognized and affirmed existing Aboriginal and treaty rights. From this recognition emerged, in 1990, the duty to consult as part of the justification framework allowing for the infringementsW of Aboriginal rights.2 The Supreme Court of Canada then went on to establish, in 2004, the duty to consult and, if appropriate, accommodate Aboriginal groups when the Crown undertakes an action or decision that could adversely affect their rights. -

Coastal Strategy for the West Coast of Vancouver Island

COASTAL STRATEGY FOR THE WEST COAST VANCOUVER ISLAND West Coast Aquatic 2012 Overview Values & Principles Vision, Goals, Objectives Priorities & Action Plans Dear Reader, As members of the West Coast Vancou- This Coastal Strategy also respects vision and approach. ver Island Aquatic Management Board, jurisdictional authority, aboriginal title we are pleased to present this Coastal and rights, and existing regulatory We look forward to pursuing this Strat- Strategy for the West Coast of Vancou- processes and plans. It does not fetter egy’s vision of a place where people are ver Island (WCVI) region. the decision-making ability of relevant working together for the benefit of cur- Ministers, Elected Officials, or Chiefs, rent and future generations of aquatic The WCVI region is one of the richest or supersede management plans, resources, people and communities, and most diverse aquatic ecosystems in Treaties, or other agreements. Rather, reflecting the principles of Hishukish the world. This Strategy was developed it provides the best available guid- tsawalk (Everything is One) and Iisaak to address opportunities and risks ance, knowledge, and tools to support (Respect). related to the health and wealth of its decision-makers. environment, communities and busi- Thank you / Klecko Klecko! nesses. As a board, we recognize the interde- pendent nature of the environment, The Strategy assists current and future society, and the economy. Each is governments, communities, sectors, dependent on the other for long-term and other partners interested -

The Struggle for Indigenous Representation in Canadian National Parks: the Case of the Haida Totem Poles in Jasper

Journal of Indigenous Research Full Circle: Returning Native Research to the People Volume 8 Issue 2020 March 2020 Article 1 March 2020 The Struggle for Indigenous Representation in Canadian National Parks: The Case of the Haida Totem Poles in Jasper Jason W. Johnston Thompson Rivers University, [email protected] Courtney Mason Thompson Rivers University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/kicjir Recommended Citation Johnston, Jason W. and Mason, Courtney (2020) "The Struggle for Indigenous Representation in Canadian National Parks: The Case of the Haida Totem Poles in Jasper," Journal of Indigenous Research: Vol. 8 : Iss. 2020 , Article 1. DOI: https://doi.org/10.26077/7t6x-ds86 Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/kicjir/vol8/iss2020/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Indigenous Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Struggle for Indigenous Representation in Canadian National Parks: The Case of the Haida Totem Poles in Jasper Cover Page Footnote To the Indigenous participants and the participants from Jasper National Park, thank you. Without your knowledge, passion and time, this project would not have been possible. While this is only the beginning, your contributions to this work will lead to a deeper understanding and appreciation for the complexities of the issues surrounding Indigenous representation in national parks. This article is available in Journal of Indigenous Research: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/kicjir/vol8/iss2020/1 Johnston and Mason: The Struggle for Indigenous Representation in Canadian National Parks The Struggle for Indigenous Representation in Canadian National Parks: The Case of the Haida Totem Poles in Jasper National parks hold an important place in the identities of many North Americans. -

Language List 2019

First Nations Languages in British Columbia – Revised June 2019 Family1 Language Name2 Other Names3 Dialects4 #5 Communities Where Spoken6 Anishnaabemowin Saulteau 7 1 Saulteau First Nations ALGONQUIAN 1. Anishinaabemowin Ojibway ~ Ojibwe Saulteau Plains Ojibway Blueberry River First Nations Fort Nelson First Nation 2. Nēhiyawēwin ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐍᐏᐣ Saulteau First Nations ALGONQUIAN Cree Nēhiyawēwin (Plains Cree) 1 West Moberly First Nations Plains Cree Many urban areas, especially Vancouver Cheslatta Carrier Nation Nak’albun-Dzinghubun/ Lheidli-T’enneh First Nation Stuart-Trembleur Lake Lhoosk’uz Dene Nation Lhtako Dene Nation (Tl’azt’en, Yekooche, Nadleh Whut’en First Nation Nak’azdli) Nak’azdli Whut’en ATHABASKAN- ᑕᗸᒡ NaZko First Nation Saik’uz First Nation Carrier 12 EYAK-TLINGIT or 3. Dakelh Fraser-Nechakoh Stellat’en First Nation 8 Taculli ~ Takulie NA-DENE (Cheslatta, Sdelakoh, Nadleh, Takla Lake First Nation Saik’uZ, Lheidli) Tl’azt’en Nation Ts’il KaZ Koh First Nation Ulkatcho First Nation Blackwater (Lhk’acho, Yekooche First Nation Lhoosk’uz, Ndazko, Lhtakoh) Urban areas, especially Prince George and Quesnel 1 Please see the appendix for definitions of family, language and dialect. 2 The “Language Names” are those used on First Peoples' Language Map of British Columbia (http://fp-maps.ca) and were compiled in consultation with First Nations communities. 3 The “Other Names” are names by which the language is known, today or in the past. Some of these names may no longer be in use and may not be considered acceptable by communities but it is useful to include them in order to assist with the location of language resources which may have used these alternate names. -

Indian Band Revenue Moneys Order Décret Sur Les Revenus Des Bandes D’Indiens

CANADA CONSOLIDATION CODIFICATION Indian Band Revenue Moneys Décret sur les revenus des Order bandes d’Indiens SOR/90-297 DORS/90-297 Current to October 11, 2016 À jour au 11 octobre 2016 Last amended on December 14, 2012 Dernière modification le 14 décembre 2012 Published by the Minister of Justice at the following address: Publié par le ministre de la Justice à l’adresse suivante : http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca http://lois-laws.justice.gc.ca OFFICIAL STATUS CARACTÈRE OFFICIEL OF CONSOLIDATIONS DES CODIFICATIONS Subsections 31(1) and (3) of the Legislation Revision and Les paragraphes 31(1) et (3) de la Loi sur la révision et la Consolidation Act, in force on June 1, 2009, provide as codification des textes législatifs, en vigueur le 1er juin follows: 2009, prévoient ce qui suit : Published consolidation is evidence Codifications comme élément de preuve 31 (1) Every copy of a consolidated statute or consolidated 31 (1) Tout exemplaire d'une loi codifiée ou d'un règlement regulation published by the Minister under this Act in either codifié, publié par le ministre en vertu de la présente loi sur print or electronic form is evidence of that statute or regula- support papier ou sur support électronique, fait foi de cette tion and of its contents and every copy purporting to be pub- loi ou de ce règlement et de son contenu. Tout exemplaire lished by the Minister is deemed to be so published, unless donné comme publié par le ministre est réputé avoir été ainsi the contrary is shown. publié, sauf preuve contraire. -

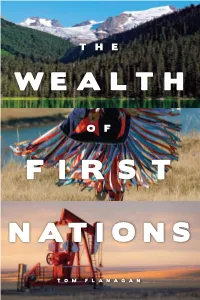

The Wealth of First Nations

The Wealth of First Nations Tom Flanagan Fraser Institute 2019 Copyright ©2019 by the Fraser Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief passages quoted in critical articles and reviews. The author of this book has worked independently and opinions expressed by him are, there- fore, his own and and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute, its Board of Directors, its donors and supporters, or its staff. This publication in no way implies that the Fraser Institute, its directors, or staff are in favour of, or oppose the passage of, any bill; or that they support or oppose any particular political party or candidate. Printed and bound in Canada National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data The Wealth of First Nations / by Tom Flanagan Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-88975-533-8. Fraser Institute ◆ fraserinstitute.org Contents Preface / v introduction —Making and Taking / 3 Part ONE—making chapter one —The Community Well-Being Index / 9 chapter two —Governance / 19 chapter three —Property / 29 chapter four —Economics / 37 chapter five —Wrapping It Up / 45 chapter six —A Case Study—The Fort McKay First Nation / 57 Part two—taking chapter seven —Government Spending / 75 chapter eight —Specific Claims—Money / 93 chapter nine —Treaty Land Entitlement / 107 chapter ten —The Duty to Consult / 117 chapter eleven —Resource Revenue Sharing / 131 conclusion —Transfers and Off Ramps / 139 References / 143 about the author / 161 acknowledgments / 162 Publishing information / 163 Purpose, funding, & independence / 164 About the Fraser Institute / 165 Peer review / 166 Editorial Advisory Board / 167 fraserinstitute.org ◆ Fraser Institute Preface The Liberal government of Justin Trudeau elected in 2015 is attempting massive policy innovations in Indigenous affairs. -

Joint Federal/Provincial Consultation and Accommodation Report for the Trans Mountain Expension Project

Joint Federal/Provincial Consultation and Accommodation Report for the Trans Mountain Expansion Project November 2016 Joint Federal/Provincial Consultation and Accommodation Report for the TRANS MOUNTAIN EXPANSION PROJECT TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms, Abbreviations and Definitions Used in This Report ...................... xi 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose of the Report ..............................................................................1 1.2 Project Description .................................................................................2 1.3 Regulatory Review Including the Environmental Assessment Process .....................7 1.3.1 NEB REGULATORY REVIEW AND ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT PROCESS ....................7 1.3.2 BRITISH COLUMBIA’S ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT PROCESS ...............................8 1.4 NEB Recommendation Report.....................................................................9 2. APPROACH TO CONSULTING ABORIGINAL GROUPS ........................... 12 2.1 Identification of Aboriginal Groups ............................................................. 12 2.2 Information Sources .............................................................................. 19 2.3 Consultation With Aboriginal Groups ........................................................... 20 2.3.1 PRINCIPLES INVOLVED IN ESTABLISHING THE DEPTH OF DUTY TO CONSULT AND IDENTIFYING THE EXTENT OF ACCOMMODATION ........................................ 24 2.3.2 PRELIMINARY -

Appendix 22-A

Appendix 22-A Simpcw First Nation Traditional Land Use and Ecological Knowledge Study HARPER CREEK PROJECT Application for an Environmental Assessment Certificate / Environmental Impact Statement SIMPCW FIRST NATION FINAL REPORT PUBLIC VERSION Traditional Land Use & Ecological Knowledge STUDY REGARDINGin THE PROPOSED YELLOWHEAD MINING INC. HARPER CREEK MINE Prepared by SFN Sustainable resources Department August 30, 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Research Team would like to thank the Simpcw First Nation (SFN), its elders, members, and leadership For the trust you’ve placed in us. We recognize all community members who contributed their knowledge oF their history, culture and territory to this work. 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The report has been the product oF a collaborative eFFort by members oF the research team and as such is presented in more than one voice. The Simpcw First Nation Traditional Land Use and Ecological Knowledge Study presents evidence oF Simpcw First Nation (SFN) current and past uses oF an area subject to the development oF the Harper Creek Mine by Yellowhead Mining, Inc. The report asserts that the Simpcw hold aboriginal title and rights in their traditional territory, including the land on which the Harper Creek Mine is proposed. This is supported by the identiFication oF one hundred and Four (104) traditional use locations in the regional study area (Simpcwul’ecw; Simpcw territory) and twenty (20) sites in the local study area. The traditional use sites identiFied, described, and mapped during this study conFirm Simpcw connections to the area where the Harper Creek Mine is proposed. These sites include Food harvesting locations like hunting places, Fishing spots, and plant gathering locations. -

A GUIDE to Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013)

A GUIDE TO Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013) A GUIDE TO Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013) INTRODUCTORY NOTE A Guide to Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia is a provincial listing of First Nation, Métis and Aboriginal organizations, communities and community services. The Guide is dependent upon voluntary inclusion and is not a comprehensive listing of all Aboriginal organizations in B.C., nor is it able to offer links to all the services that an organization may offer or that may be of interest to Aboriginal people. Publication of the Guide is coordinated by the Intergovernmental and Community Relations Branch of the Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation (MARR), to support streamlined access to information about Aboriginal programs and services and to support relationship-building with Aboriginal people and their communities. Information in the Guide is based upon data available at the time of publication. The Guide data is also in an Excel format and can be found by searching the DataBC catalogue at: http://www.data.gov.bc.ca. NOTE: While every reasonable effort is made to ensure the accuracy and validity of the information, we have been experiencing some technical challenges while updating the current database. Please contact us if you notice an error in your organization’s listing. We would like to thank you in advance for your patience and understanding as we work towards resolving these challenges. If there have been any changes to your organization’s contact information please send the details to: Intergovernmental and Community Relations Branch Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation PO Box 9100 Stn Prov.