ELITE CONFLICT in the POST-MAO CHINA (Revised Edition 1983)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China Data Supplement

China Data Supplement October 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 29 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 36 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 42 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 45 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR................................................................................................................ 54 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR....................................................................................................................... 61 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 66 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 October 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

Beijing's Inte

Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Hearing on What Keeps Xi Up at Night: Beijing’s Internal and External Challenges February 7, 2019 Greg Levesque Managing Director, Pointe Bello Beijing Crafting a 21st Century Industrial Policy The Peoples Republic of China (PRC) is implementing an ambitious strategy to rapidly enhance its innovation capabilities to close the scientific and technological innovation gap with more advanced economies such as the United States. A number of internal and external factors are motivating this effort, but at a macro-level, PRC leaders assess that the world has entered a fast-moving technological revolution characterized by “informatization and intelligentization” [智能化·] with implications for global economic and military affairs. Simultaneously, and arguably coincidentally, the 2008 Financial Crisis created further strategic opportunities1 for China to expand its influence amid anticipated shifts in the global balance of power. The convergence of this “technological moment” and “strategic moment” are resulting in rapid changes to PRC industrial, innovation, and military modernization policies and capture the underpinnings of Chinese competitive strategy. General Secretary Xi outlined this perspective in a 2013 speech to the Politburo, stating: “At present, from a global perspective, science and technology are increasingly becoming the main force driving economic and social development, and innovation is the general trend…Since the outbreak of the international financial crisis, major countries in the world have made great efforts to formulate new science and technology development strategies to seize the commanding heights of science and technology and industry. This trend deserves our high attention.”2 PRC industrial policy emphasizing development of “core technologies” [核心技术]3 appear strongly influenced by internal assessments of the 2008 Financial Crisis, leading to shifts in policy across economic, diplomatic, and military domains. -

Adaptive Fuzzy Pid Controller's Application in Constant Pressure Water Supply System

2010 2nd International Conference on Information Science and Engineering (ICISE 2010) Hangzhou, China 4-6 December 2010 Pages 1-774 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP1076H-PRT ISBN: 978-1-4244-7616-9 1 / 10 TABLE OF CONTENTS ADAPTIVE FUZZY PID CONTROLLER'S APPLICATION IN CONSTANT PRESSURE WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM..............................................................................................................................................................................................................1 Xiao Zhi-Huai, Cao Yu ZengBing APPLICATION OF OPC INTERFACE TECHNOLOGY IN SHEARER REMOTE MONITORING SYSTEM ...............................5 Ke Niu, Zhongbin Wang, Jun Liu, Wenchuan Zhu PASSIVITY-BASED CONTROL STRATEGIES OF DOUBLY FED INDUCTION WIND POWER GENERATOR SYSTEMS.................................................................................................................................................................................9 Qian Ping, Xu Bing EXECUTIVE CONTROL OF MULTI-CHANNEL OPERATION IN SEISMIC DATA PROCESSING SYSTEM..........................14 Li Tao, Hu Guangmin, Zhao Taiyin, Li Lei URBAN VEGETATION COVERAGE INFORMATION EXTRACTION BASED ON IMPROVED LINEAR SPECTRAL MIXTURE MODE.....................................................................................................................................................................18 GUO Zhi-qiang, PENG Dao-li, WU Jian, GUO Zhi-qiang ECOLOGICAL RISKS ASSESSMENTS OF HEAVY METAL CONTAMINATIONS IN THE YANCHENG RED-CROWN CRANE NATIONAL NATURE RESERVE BY SUPPORT -

1992 a Glorious Model of Proletarian Internationalism: Mao Zedong and Helping Vietnam Resist France

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified 1992 A Glorious Model of Proletarian Internationalism: Mao Zedong and Helping Vietnam Resist France Citation: “A Glorious Model of Proletarian Internationalism: Mao Zedong and Helping Vietnam Resist France,” 1992, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Luo Guibo, "Wuchanjieji guojizhuyide guanghui dianfan: yi Mao Zedong he Yuan-Yue Kang-Fa" ("A Glorious Model of Proletarian Internationalism: Mao Zedong and Helping Vietnam Resist France"), in Mianhuai Mao Zedong (Remembering Mao Zedong), ed. Mianhuai Mao Zedong bianxiezhu (Beijing: Zhongyang Wenxian chubanshe, 1992) 286-299. Translated by Emily M. Hill http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/120359 Summary: Luo Guibo recounts China's involvement in the First Indochina War and its assistance to the Viet Minh. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the MacArthur Foundation and the Leon Levy Foundation. Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation One Late in 1949, soon after the establishment of New China, Chairman Ho Chi Minh and the Central Committee of the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP) wrote to Chairman Mao and the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), asking for Chinese assistance. In January 1950, Ho made a secret visit to Beijing to request Chinaʼs assistance in Vietnamʼs struggle against France. Following Hoʼs visit, the CCP Central Committee made the decision, authorized by Chairman Mao, to send me on a secret mission to Vietnam. I was formally appointed as the Liaison Representative of the CCP Central Committee to the ICP Central Committee. Comrade [Liu] Shaoqi personally composed a letter of introduction, which stated: ʻI hereby recommend to your office Comrade Luo Guibo, who has been a provincial Party secretary and commissar, as the Liaison Representative of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party. -

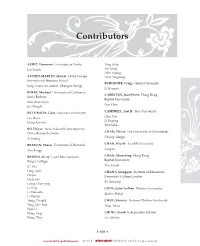

Contributors.Indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM F-479 /203/BER00069/Work/Indd/%20Backmatter

02_Contributors.indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM f-479 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter Contributors AUBIÉ, Hermann University of Turku Yang Jiang Liu Xiaobo Yao Ming Zhao Ziyang AUSTIN-MARTIN, Marcel China Europe Zhou Youguang International Business School BURGDOFF, Craig Capital University Jiang Zemin (co-author: Zhengxu Wang) Li Hongzhi BERRY, Michael University of California, CABESTAN, Jean-Pierre Hong Kong Santa Barbara Baptist University Hou Hsiao-hsien Lien Chan Jia Zhangke CAMPBELL, Joel R. Troy University BETTINSON, Gary Lancaster University Chen Yun Lee, Bruce Li Keqiang Wong Kar-wai Wen Jiabao BO Zhiyue New Zealand Contemporary CHAN, Felicia The University of Manchester China Research Centre Cheung, Maggie Xi Jinping BRESLIN, Shaun University of Warwick CHAN, Hiu M. Cardiff University Zhu Rongji Gong Li BROWN, Kerry Lau China Institute, CHAN, Shun-hing Hong Kong King’s College Baptist University Bo Yibo Zen, Joseph Fang Lizhi CHANG Xiangqun Institute of Education, Hu Jia University College London Hu Jintao Fei Xiaotong Leung Chun-ying Li Peng CHEN, Julie Yu-Wen Palacky University Li Xiannian Kadeer, Rebiya Li Xiaolin Tsang, Donald CHEN, Szu-wei National Taiwan University Tung Chee-hwa Teng, Teresa Wan Li Wang Yang CHING, Frank Independent Scholar Wang Zhen Lee, Martin • 569 • www.berkshirepublishing.com © 2015 Berkshire Publishing grouP, all rights reserved. 02_Contributors.indd Page 570 9/22/15 12:09 PM f-500 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter • Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography • Volume 4 • COHEN, Jerome A. New -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript Pas been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissenation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from anytype of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material bad to beremoved, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with smalloverlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back ofthe book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell &Howell Information Company 300North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106-1346 USA 313!761-47oo 800:521·0600 THE LIN BIAO INCIDENT: A STUDY OF EXTRA-INSTITUTIONAL FACTORS IN THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY AUGUST 1995 By Qiu Jin Dissertation Committee: Stephen Uhalley, Jr., Chairperson Harry Lamley Sharon Minichiello John Stephan Roger Ames UMI Number: 9604163 OMI Microform 9604163 Copyright 1995, by OMI Company. -

The Mishu Phenomenon: Patron-Client Ties and Coalition-Building Tactics

Li, China Leadership Monitor No.4 The Mishu Phenomenon: Patron-Client Ties and Coalition-Building Tactics Cheng Li China’s ongoing political succession has been filled with paradoxes. Jockeying for power among various factions has been fervent and protracted, but the power struggle has not led to a systemic crisis as it did during the reigns of Mao and Deng. While nepotism and favoritism in elite recruitment have become prevalent, educational credentials and technical expertise are also essential. Regional representation has gained importance in the selection of Central Committee members, but leaders who come from coastal regions will likely dominate the new Politburo. Regulations such as term limits and an age requirement for retirement have been implemented at various levels of the Chinese leadership, but these rules and norms will perhaps not restrain the power of Jiang Zemin, the 76-year-old “new paramount leader.” While the military’s influence on political succession has declined during the past decade, the Central Military Commission is still very powerful. Not surprisingly, these paradoxical developments have led students of Chinese politics to reach contrasting assessments of the nature of this political succession, the competence of the new leadership, and the implications of these factors for China’s future. This diversity of views is particularly evident regarding the ubiquitous role of mishu in the Chinese leadership. The term mishu, which literally means “secretary” in Chinese, refers to a range of people who differ significantly from each other in terms of the functions they fulfill, the leadership bodies they serve, and the responsibilities given to them. -

Marriage Practice of the Chinese Communist Party in Modern Era, 1910S-1950S

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-23-2011 12:00 AM From Marriage Revolution to Revolutionary Marriage: Marriage Practice of the Chinese Communist Party in Modern Era, 1910s-1950s Wei Xu The University of Western Ontario Supervisor James Flath The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Wei Xu 2011 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Asian History Commons, Chinese Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, History of Gender Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons, Social History Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Xu, Wei, "From Marriage Revolution to Revolutionary Marriage: Marriage Practice of the Chinese Communist Party in Modern Era, 1910s-1950s" (2011). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 232. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/232 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM MARRIAGE REVOLUTION TO REVOLUTIONARY MARRIAGE: MARRIAGE PRACTICE OF THE CHINESE COMMUNIST PARTY IN MODERN ERA 1910s-1950s (Spine -

History of China: Table of Contents

History of China: Table of Contents ● Historical Setting ● The Ancient Dynasties ❍ Dawn of History ❍ Zhou Period ❍ Hundred Schools of Thought ● The Imperial Era ❍ First Imperial Period ❍ Era of Disunity ❍ Restoration of Empire ❍ Mongolian Interlude ❍ Chinese Regain Power ❍ Rise of the Manchus ● Emergence Of Modern China ❍ Western Powers Arrive First Modern Period ❍ Opium War, 1839-42 Era of Disunity ❍ Taiping Rebellion, 1851-64 ❍ Self-Strengthening Movement ❍ Hundred Days' Reform and Aftermath ❍ Republican Revolution of 1911 ● Republican China ❍ Nationalism and Communism ■ Opposing the Warlords ■ Consolidation under the Guomindang ■ Rise of the Communists ❍ Anti-Japanese War ❍ Return to Civil War ● People's Republic Of China ❍ Transition to Socialism, 1953-57 ❍ Great Leap Forward, 1958-60 ❍ Readjustment and Recovery, 1961-65 ❍ Cultural Revolution Decade, 1966-76 ■ Militant Phase, 1966-68 ■ Ninth National Party Congress to the Demise of Lin Biao, 1969-71 ■ End of the Era of Mao Zedong, 1972-76 ❍ Post-Mao Period, 1976-78 ❍ China and the Four Modernizations, 1979-82 ❍ Reforms, 1980-88 ● References for History of China [ History of China ] [ Timeline ] Historical Setting The History Of China, as documented in ancient writings, dates back some 3,300 years. Modern archaeological studies provide evidence of still more ancient origins in a culture that flourished between 2500 and 2000 B.C. in what is now central China and the lower Huang He ( orYellow River) Valley of north China. Centuries of migration, amalgamation, and development brought about a distinctive system of writing, philosophy, art, and political organization that came to be recognizable as Chinese civilization. What makes the civilization unique in world history is its continuity through over 4,000 years to the present century. -

From Textual to Historical Networks: Social Relations in the Bio-Graphical Dictionary of Republican China Cécile Armand, Christian Henriot

From Textual to Historical Networks: Social Relations in the Bio-graphical Dictionary of Republican China Cécile Armand, Christian Henriot To cite this version: Cécile Armand, Christian Henriot. From Textual to Historical Networks: Social Relations in the Bio-graphical Dictionary of Republican China. Journal of Historical Network Research, In press. halshs-03213995 HAL Id: halshs-03213995 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03213995 Submitted on 8 Jun 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ARMAND, CÉCILE HENRIOT, CHRISTIAN From Textual to Historical Net- works: Social Relations in the Bio- graphical Dictionary of Republi- can China Journal of Historical Network Research x (202x) xx-xx Keywords Biography, China, Cooccurrence; elites, NLP From Textual to Historical Networks 2 Abstract In this paper, we combine natural language processing (NLP) techniques and network analysis to do a systematic mapping of the individuals mentioned in the Biographical Dictionary of Republican China, in order to make its underlying structure explicit. We depart from previous studies in the distinction we make between the subject of a biography (bionode) and the individuals mentioned in a biography (object-node). We examine whether the bionodes form sociocentric networks based on shared attributes (provincial origin, education, etc.). -

(Hrsg.) Strafrecht in Reaktion Auf Systemunrecht

Albin Eser / Ulrich Sieber / Jörg Arnold (Hrsg.) Strafrecht in Reaktion auf Systemunrecht Schriftenreihe des Max-Planck-Instituts für ausländisches und internationales Strafrecht Strafrechtliche Forschungsberichte Herausgegeben von Ulrich Sieber in Fortführung der Reihe „Beiträge und Materialien aus dem Max-Planck-Institut für ausländisches und internationales Strafrecht Freiburg“ begründet von Albin Eser Band S 82.9 Strafrecht in Reaktion auf Systemunrecht Vergleichende Einblicke in Transitionsprozesse herausgegeben von Albin Eser • Ulrich Sieber • Jörg Arnold Band 9 China von Thomas Richter sdfghjk Duncker & Humblot • Berlin Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über <http://dnb.ddb.de> abrufbar. DOI https://doi.org/10.30709/978-3-86113-876-X Redaktion: Petra Lehser Alle Rechte vorbehalten © 2006 Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften e.V. c/o Max-Planck-Institut für ausländisches und internationales Strafrecht Günterstalstraße 73, 79100 Freiburg i.Br. http://www.mpicc.de Vertrieb in Gemeinschaft mit Duncker & Humblot GmbH, Berlin http://WWw.duncker-humblot.de Umschlagbild: Thomas Gade, © www.medienarchiv.com Druck: Stückle Druck und Verlag, Stückle-Straße 1, 77955 Ettenheim Printed in Germany ISSN 1860-0093 ISBN 3-86113-876-X (Max-Planck-Institut) ISBN 3-428-12129-5 (Duncker & Humblot) Gedruckt auf alterungsbeständigem (säurefreiem) Papier entsprechend ISO 9706 # Vorwort der Herausgeber Mit dem neunten Band der Reihe „Strafrecht in Reaktion auf Systemunrecht – Vergleichende Einblicke in Transitionsprozesse“ wird zur Volksrepublik China ein weiterer Landesbericht vorgelegt. Während die bisher erschienenen Bände solche Länder in den Blick nahmen, die hinsichtlich der untersuchten Transitionen einem „klassischen“ Systemwechsel von der Diktatur zur Demokratie entsprachen, ist die Einordung der Volksrepublik China schwieriger. -

Xi Jinping and the Party Apparatus

Miller, China Leadership Monitor, No. 25 Xi Jinping and the Party Apparatus Alice Miller In the six months since the 17th Party Congress, Xi Jinping’s public appearances indicate that he has been given the task of day-to-day supervision of the Party apparatus. This role will allow him to expand and consolidate his personal relationships up and down the Party hierarchy, a critical opportunity in his preparation to succeed Hu Jintao as Party leader in 2012. In particular, as Hu Jintao did in his decade of preparation prior to becoming top Party leader in 2002, Xi presides over the Party Secretariat. Traditionally, the Secretariat has served the Party’s top policy coordinating body, supervising implementation of decisions made by the Party Politburo and its Standing Committee. For reasons that are not entirely clear, Xi’s Secretariat has been significantly trimmed to focus solely on the Party apparatus, and has apparently relinquished its longstanding role in coordinating decisions in several major sectors of substantive policy. Xi’s Activities since the Party Congress At the First Plenum of the Chinese Communist Party’s 17th Central Committee on 22 October 2007, Xi Jinping was appointed sixth-ranking member of the Politburo Standing Committee and executive secretary of the Party Secretariat. In December 2007, he was also appointed president of the Central Party School, the Party’s finishing school for up and coming leaders and an important think-tank for the Party’s top leadership. On 15 March 2008, at the 11th National People’s Congress (NPC), Xi was also elected PRC vice president, a role that gives him enhanced opportunity to meet with visiting foreign leaders and to travel abroad on official state business.