The Journal the Music Academy M a D R a S'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music Initiative Jka Peer - Reviewed Journal of Music

VOL. 01 NO. 01 APRIL 2018 MUSIC INITIATIVE JKA PEER - REVIEWED JOURNAL OF MUSIC PUBLISHED,PRINTED & OWNED BY HIGHER EDUCATION DEPARTMENT, J&K CIVIL SECRETARIAT, JAMMU/SRINAGAR,J&K CONTACT NO.S: 01912542880,01942506062 www.jkhighereducation.nic.in EDITOR DR. ASGAR HASSAN SAMOON (IAS) PRINCIPAL SECRETARY HIGHER EDUCATION GOVT. OF JAMMU & KASHMIR YOOR HIGHER EDUCATION,J&K NOT FOR SALE COVER DESIGN: NAUSHAD H GA JK MUSIC INITIATIVE A PEER - REVIEWED JOURNAL OF MUSIC INSTRUCTION TO CONTRIBUTORS A soft copy of the manuscript should be submitted to the Editor of the journal in Microsoft Word le format. All the manuscripts will be blindly reviewed and published after referee's comments and nally after Editor's acceptance. To avoid delay in publication process, the papers will not be sent back to the corresponding author for proof reading. It is therefore the responsibility of the authors to send good quality papers in strict compliance with the journal guidelines. JK Music Initiative is a quarterly publication of MANUSCRIPT GUIDELINES Higher Education Department, Authors preparing submissions are asked to read and follow these guidelines strictly: Govt. of Jammu and Kashmir (JKHED). Length All manuscripts published herein represent Research papers should be between 3000- 6000 words long including notes, bibliography and captions to the opinion of the authors and do not reect the ofcial policy illustrations. Manuscripts must be typed in double space throughout including abstract, text, references, tables, and gures. of JKHED or institution with which the authors are afliated unless this is clearly specied. Individual authors Format are responsible for the originality and genuineness of the work Documents should be produced in MS Word, using a single font for text and headings, left hand justication only and no embedded formatting of capitals, spacing etc. -

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free Static GK E-Book

oliveboard FREE eBooks FAMOUS INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSICIANS & VOCALISTS For All Banking and Government Exams Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free static GK e-book Current Affairs and General Awareness section is one of the most important and high scoring sections of any competitive exam like SBI PO, SSC-CGL, IBPS Clerk, IBPS SO, etc. Therefore, we regularly provide you with Free Static GK and Current Affairs related E-books for your preparation. In this section, questions related to Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists have been asked. Hence it becomes very important for all the candidates to be aware about all the Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. In all the Bank and Government exams, every mark counts and even 1 mark can be the difference between success and failure. Therefore, to help you get these important marks we have created a Free E-book on Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. The list of all the Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists is given in the following pages of this Free E-book on Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. Sample Questions - Q. Ustad Allah Rakha played which of the following Musical Instrument? (a) Sitar (b) Sarod (c) Surbahar (d) Tabla Answer: Option D – Tabla Q. L. Subramaniam is famous for playing _________. (a) Saxophone (b) Violin (c) Mridangam (d) Flute Answer: Option B – Violin Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free static GK e-book Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. Name Instrument Music Style Hindustani -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

Sadir, Bharatanatyam, Feminist Theory Sriv1dya

ANOTHER STAGE IN THE LIFE OP THE NATION: SADIR, BHARATANATYAM, FEMINIST THEORY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES SRIV1DYA NATARAJAN FEBRUARY, 1997 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that Ms. Srividya Natarajan worked under my supervision for the Ph.D. Degree in English. Her thesis entitled "Another Stage in the Life of the Nation: Sadir. Bharatanatyam. Feminist Theory" represents her own independent work at the University of Hyderabad. This work has not been submitted to any other institution for the award of any degree. Hyderabad Tejaswini Niranjana Date: 14-02-1997 Department of English School of Humanities University of Hyderabad Hyderabad February 12, 1997 This is to certify that I, Srividya Natarajan, have carried out the research embodied in the present thesis for the full period prescribed under Ph.D. ordinances of the University. I declare to the best of my knowledge that no part of this thesis was earlier submitted for the award of research degree of any University. To those special teachers from whose lives I have learnt more than from all my other education put together: Kittappa Vadhyar, Paati, Thatha, Paddu, Mythili, Nigel. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the course of five years of work on this thesis, I have piled up more debts than I can acknowledge in due measure. A fellowship from the University Grants Commission gave me leisure for full-time research; some of this time was spent among the stacks of the Tamil Nadu Archives, the Madras University Library, the Music Academy Library, the Adyar Library, the T.T. -

The Inner Light: the Beatles, India, Gurus, and the Legacy

The Inner Light: The Beatles, India, Gurus, and the Legacy John Covach Institute for Popular Music, University of Rochester Arthur Satz Department of Music Eastman School of Music Main Points The Beatles’ “road to India” is mostly navigated by George Harrison John Lennon was also enthusiastic, Paul somewhat, Ringo not so much Harrison’s “road to India” can be divided into two kinds of influence: Musical influences—the actual sounds and structures of Indian music Philosophical and spiritual influences—elements that influence lyrics and lifestyle The musical influences begin in April 1965, become focused in fall 1966, and extend to mid 1968 The philosophical influences begin in late 1966 and continue through the rest of Harrison’s life Note: Harrison began using LSD in the spring of 1965 and discontinued in August 1967 Songs by other Beatles, Lennon especially, also reflect Indian influences The Three “Indian” songs of George Harrison “Love You To” recorded April 1966, released on Revolver, August 1966 “Within You Without You” recorded March, April 1967, released on Sgt Pepper, June 1967 “The Inner Light” recorded January, February 1968, released as b-side to “Lady Madonna,” March 1968 Three Aspects of “Indian” characteristics Use of some aspect of Indian philosophy or spirituality in the lyrics Use of Indian musical instruments Use of Indian musical features (rhythmic patterns, drone, texture, melodic elements) Musical Influences Ravi Shankar is principal influence on Harrison, though he does not enter the picture until mid 1966 April 1965: Beatles film restaurant scene for Help! Harrison falls in love with the sitar, buys one cheap Summer 1965: Beatles in LA hear about Shankar from McGuinn, Crosby (meet Elvis, discuss Yogananda) October 1965: “Norwegian Wood” recorded, released in December on Rubber Soul. -

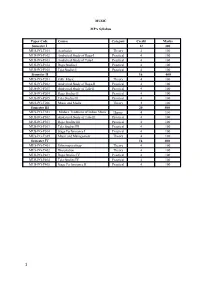

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks Semester I 12 300 MUS-PG-T101 Aesthetics Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P102 Analytical Study of Raga-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P103 Analytical Study of Tala-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P104 Raga Studies I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P105 Tala Studies I Practical 4 100 Semester II 16 400 MUS-PG-T201 Folk Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P202 Analytical Study of Raga-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P203 Analytical Study of Tala-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P204 Raga Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P205 Tala Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T206 Music and Media Theory 4 100 Semester III 20 500 MUS-PG-T301 Modern Traditions of Indian Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P302 Analytical Study of Tala-III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Raga Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Tala Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P304 Stage Performance I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T305 Music and Management Theory 4 100 Semester IV 16 400 MUS-PG-T401 Ethnomusicology Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-T402 Dissertation Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P403 Raga Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P404 Tala Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P405 Stage Performance II Practical 4 100 1 Semester I MUS-PG-CT101:- Aesthetic Course Detail- The course will primarily provide an overview of music and allied issues like Aesthetics. The discussions will range from Rasa and its varieties [According to Bharat, Abhinavagupta, and others], thoughts of Rabindranath Tagore and Abanindranath Tagore on music to aesthetics and general comparative. -

St. Joseph's College for Women, Tirupur, Tamilnadu

==================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 18:10 October 2018 India’s Higher Education Authority UGC Approved List of Journals Serial Number 49042 ==================================================================== St. Joseph’s College for Women, Tirupur, Tamilnadu R. Rajalakshmi, Editor Select Papers from the Conference Reading the Nation – The Global Perspective • Greetings from the Principal ... Rev. Sr. Dr. Kulandai Therese. A i • Editor's Preface ... R. Rajalakshmi, Assistant Professor and Head Department of English ii • Caste and Nation in Indian Society ... CH. Chandra Mouli & B. Sridhar Kumar 1-16 =============================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 18:10 October 2018 R. Rajalakshmi, Editor: Reading the Nation – The Global Perspective • Nationalism and the Postcolonial Literatures ... Dr. K. Prabha 17-21 • A Study of Men-Women Relationship in the Selected Novels of Toni Morrison ... G. Giriya, M.A., B.Ed., M.Phil., Ph.D. Research Scholar & Dr. M. Krishnaraj 22-27 • Historicism and Animalism – Elements of Convergence in George Orwell’s Animal Farm ... Ms. Veena SP 28-34 • Expatriate Immigrants’ Quandary in the Oeuvres of Bharati Mukherjee ... V. Jagadeeswari, Assistant Professor of English 35-41 • Post-Colonial Reflections in Peter Carey’s Journey of a Lifetime ... Meera S. Menon II B.A. English Language & Literature 42-45 • Retrieval of the Mythical and Dalit Imagination in Cho Dharman’s Koogai: The Owl ... R. Murugesan Ph.D. Research Scholar 46-50 • Racism in Nadine Gordimer’s The House Gun ... Mrs. M. Nathiya Assistant Professor 51-55 • Mysteries Around the Sanctum with Special Reference To The Man From Chinnamasta by Indira Goswami ... Mrs. T. Vanitha, M.A., M.Ed., M.Phil., Ph.D. -

Bharatanatyam: Eroticism, Devotion, and a Return to Tradition

BHARATANATYAM: EROTICISM, DEVOTION, AND A RETURN TO TRADITION A THESIS Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Religion In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Taylor Steine May/2016 Page 1! of 34! Abstract The classical Indian dance style of Bharatanatyam evolved out of the sadir dance of the devadāsīs. Through the colonial period, the dance style underwent major changes and continues to evolve today. This paper aims to examine the elements of eroticism and devotion within both the sadir dance style and the contemporary Bharatanatyam. The erotic is viewed as a religious path to devotion and salvation in the Hindu religion and I will analyze why this eroticism is seen as religious and what makes it so vital to understanding and connecting with the divine, especially through the embodied practices of religious dance. Introduction Bharatanatyam is an Indian dance style that evolved from the sadir dance of devadāsīs. Sadir has been popular since roughly the 6th century. The original sadir dance form most likely originated in the area of Tamil Nadu in southern India and was used in part for temple rituals. Because of this connection to the ancient sadir dance, Bharatanatyam has historic traditional value. It began as a dance style performed in temples as ritual devotion to the gods. This original form of the style performed by the devadāsīs was inherently religious, as devadāsīs were women employed by the temple specifically to perform religious texts for the deities and for devotees. Because some sadir pieces were dances based on poems about kings and not deities, secularism does have a place in the dance form. -

Jagannatha Das Babaji Maharaja

VAISNAVA SARVABHAUMA SRILA JAGANNATHA DASA BABAJI The following article appears in the sixth year of the monthly publications of the Gaudiya magazine under the direct guidance of Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura. It is written by the head school master of Satrujit High School, Sri Yanunandana Adhikari, a disciple of Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura. It was the second year after the opening of the Sri Caitanya Matha in Vrndavana. The resident devotees had left for Delhi to preach the glories of the Supreme Personality of Godhead, Sri Krsna. I had remained behind the others because I often become ill at the festivals. Three or four days had passed since the devotees had departed. My mind was feeling somewhat restless and uncomfortable. I was sitting alone upstairs on the veranda in front of the door to my room. I was gazing here and there empty minded. It was now about 10:00 AM when the old Vaisnava Vrndavana resident arrived. He entered into the temple grounds from the front entrance and gradually made his way up the flight of stairs. As the old figure climbed the stairs he stopped for a few moments to gain his balance. He had stumped his foot. I paid my obeisances unto the old Vaisnava and offered him a sitting place on a nearby large rug. As he gasped in short drawn breaths it was apparent that he was exhausted from his travels abroad. The mood in which he humbly introduced himself would be recognized by many Vaisnavas. I had met this venerable Vaisnava on a previous occasion. -

4 Broadcast Sector

MINISTRY OF INFORMATION AND BROADCASTING Annual Report 2006-2007 CONTENTS Highlights 1. Overview 1 2. Administration 3 3. Information Sector 12 4. Broadcast Sector 53 5. Films Sector 110 6. International Co-operation 169 7. Plan and Non-Plan Programmes 171 8. New Initiatives 184 Appendices I. Organisation Chart of the Ministry 190 II. Media-wise Budget for 2006-2007 and 2007-2008 192 Published by the Director, Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India Typeset at : Quick Prints, C-111/1, Naraina, Phase - I, New Delhi. Printed at : Overview 3 HIGHLIGHTS OF THE YEAR The 37th Edition of International Film Festival of India-2006 was organized in Goa from 23rd November to 3rd December 2006 in collaboration with State Government of Goa. Shri Shashi Kapoor was the Chief Guest for the inaugural function. Indian Film Festivals were organized under CEPs/Special Festivals abroad at Israel, Beijing, Shanghai, South Africa, Brussels and Germany. Indian films also participated in different International Film Festivals in 18 countries during the year till December, 2006. The film RAAM bagged two awards - one for the best actor and the other for the best music in the 1st Cyprus International Film Festival. The film ‘MEENAXI – A Tale of Three Cities’ also bagged two prizes—one for best cinematography and the other for best production design. Films Division participated in 6 International Film Festivals with 60 films, 4 National Film Festivals with 28 films and 21 State level film festivals with 270 films, during the period 1-04-06 to 30-11-06. Films Division Released 9791 prints of 39 films, in the theatrical circuits, from 1-4-06 to 30-11-06. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita