Sadir, Bharatanatyam, Feminist Theory Sriv1dya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mechanical Aspire

Newsletter Volume 6, Issue 11, November 2016 Mechanical Aspire Achievements in Sports, Projects, Industry, Research and Education All About Nobel Prize- Part 35 The Breakthrough Prize Inspired by Nobel Prize, there have been many other prizes similar to that, both in amount and in purpose. One such prize is the Breakthrough Prize. The Breakthrough Prize is backed by Facebook chief executive Mark Zuckerberg and Google co-founder Sergey Brin, among others. The Breakthrough Prize was founded by Brin and Anne Wojcicki, who runs genetic testing firm 23andMe, Chinese businessman Jack Ma, and Russian entrepreneur Yuri Milner and his wife Julia. The Breakthrough Prizes honor important, primarily recent, achievements in the categories of Fundamental Physics, Life Sciences and Mathematics . The prizes were founded in 2012 by Sergey Brin and Anne Wojcicki, Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan, Yuri and Julia Milner, and Jack Ma and Cathy Zhang. Committees of previous laureates choose the winners from candidates nominated in a process that’s online and open to the public. Laureates receive $3 million each in prize money. They attend a televised award ceremony designed to celebrate their achievements and inspire the next generation of scientists. As part of the ceremony schedule, they also engage in a program of lectures and discussions. Those that go on to make fresh discoveries remain eligible for future Breakthrough Prizes. The Trophy The Breakthrough Prize trophy was created by Olafur Eliasson. “The whole idea for me started out with, ‘Where do these great ideas come from? What type of intuition started the trajectory that eventually becomes what we celebrate today?’” Like much of Eliasson's work, the sculpture explores the common ground between art and science. -

New and Bestselling Titles Sociology 2016-2017

New and Bestselling titles Sociology 2016-2017 www.sagepub.in Sociology | 2016-17 Seconds with Alice W Clark How is this book helpful for young women of Any memorable experience that you hadhadw whilehile rural areas with career aspirations? writing this book? Many rural families are now keeping their girls Becoming part of the Women’s Studies program in school longer, and this book encourages at Allahabad University; sharing in the colourful page 27A these families to see real benefit for themselves student and faculty life of SNDT University in supporting career development for their in Mumbai; living in Vadodara again after daughters. It contributes in this way by many years, enjoying friends and colleagues; identifying the individual roles that can be played reconnecting with friendships made in by supportive fathers and mothers, even those Bangalore. Being given entrée to lively students with very little education themselves. by professors who cared greatly about them. Being treated wonderfully by my interviewees. What facets of this book bring-in international Any particular advice that you would like to readership? share with young women aiming for a successful Views of women’s striving for self-identity career? through professionalism; the factors motivating For women not yet in college: Find supporters and encouraging them or setting barriers to their in your family to help argue your case to those accomplishments. who aren’t so supportive. Often it’s submissive Upward trends in women’s education, the and dutiful mothers who need a prompt from narrowing of the gender gap, and the effects a relative with a broader viewpoint. -

Bharatanatyam: Eroticism, Devotion, and a Return to Tradition

BHARATANATYAM: EROTICISM, DEVOTION, AND A RETURN TO TRADITION A THESIS Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Religion In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Taylor Steine May/2016 Page 1! of 34! Abstract The classical Indian dance style of Bharatanatyam evolved out of the sadir dance of the devadāsīs. Through the colonial period, the dance style underwent major changes and continues to evolve today. This paper aims to examine the elements of eroticism and devotion within both the sadir dance style and the contemporary Bharatanatyam. The erotic is viewed as a religious path to devotion and salvation in the Hindu religion and I will analyze why this eroticism is seen as religious and what makes it so vital to understanding and connecting with the divine, especially through the embodied practices of religious dance. Introduction Bharatanatyam is an Indian dance style that evolved from the sadir dance of devadāsīs. Sadir has been popular since roughly the 6th century. The original sadir dance form most likely originated in the area of Tamil Nadu in southern India and was used in part for temple rituals. Because of this connection to the ancient sadir dance, Bharatanatyam has historic traditional value. It began as a dance style performed in temples as ritual devotion to the gods. This original form of the style performed by the devadāsīs was inherently religious, as devadāsīs were women employed by the temple specifically to perform religious texts for the deities and for devotees. Because some sadir pieces were dances based on poems about kings and not deities, secularism does have a place in the dance form. -

Tne Qjlassical Uoicinq Ine Miooern

tne Qjlassical J J Uoicinq ine Miooern THE POSTCOLONIAL POLITICS OF MUSIC IN SOUTH INDIA amandaj. weidman O O M I CALCUTTA 2007 Contents Date: v-> First published by Duke University Press in 2006 List of Illustrations vii © 2006 Duke University Press This edition printed in arrangement with Duke University Press Acknowledgments ix For publication and sale in India, Bangladesh, Burma, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, Note on Transliteration and Spelling xvii Nepal and Pakistan only Introduction l ISBN 81 7046 319 X 1. Gone Native?: Travels of Typset in Bembo by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. the Violin in South India 25 Book design by Amy Ruth Buchanan Cover design by Sunandini Banerjee 2. From the Palace to the Street: Staging "Classical" Music 59 Published by Naveen Kishore, Seagull Books Pvt Ltd 26 Circus Avenue, Calcutta 700 017 3. Gender and the Politics of Voice ill Printed at Rockewel Offset 4. Can the Subaltern Sing?: Music, 55B Mirza Ghalib Street, Calcutta 700 016 Language, and the Politics of Voice 150 Exclusively distributed in India and South Asia by Cambridge University Press India Pvt Ltd 5. A Writing Lesson: Musicology Cambridge House, 4381/4 Ansari Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi 110 002 and the Birth of the Composer 192 Portions of Chapter 3 were previously published as "Gender and the politics of voice: Colonial 6. Fantastic Fidelities 245 modernity and classical music in South India," in Cultural Anthropology 18, no. 2 (2003): 194-232. © 2003 American Anthropological Association. Afterword: Modernity and the Voice 286 Portions of Chapter 4 were previously published as "Can the subaltern sing? Music, language, Notes 291 and the politics of voice in twentieth-century South India," in Indian Economic and Social History Review 42, no. -

Dr. Padma Sugavanam AIR A-Graded Carnatic Musician – Vocalist

Dr. Padma Sugavanam AIR A-graded Carnatic Musician – Vocalist, Academic and Researcher New No 14, First floor, 3rd Avenue, Besant Nagar, Chennai – 600090 E-mail : [email protected]; Ph: +91-9949121122, 044-24910306 Experience and Credentials - Performance A-Grade artiste (AIR) specially double promoted (from B-grade, skipping B-high), since 2002 Most outstanding vocalist (junior) award from the Music Academy, Chennai in 2014, followed by promotion to the sub-senior category in 2015 Sought-after vocalist, gave 60 performances in 2016 across India, US, Canada, Singapore, Malaysia Performances in leading Sabhas (Music Academy, Krishna Gana Sabha, Parthasarathy Swami Sabha, Mylapore Fine Arts etc.) during December Margazhi music festival in Chennai Lecture-demonstrations at prestigious forums such as the Madras Music Academy, and the Ivy League institution, University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, USA) Six international concert tours, including an 18 concerts tour of USA and Canada (including the Cleveland Tyagaraja Aradhana), and a tour of Singapore and Malaysia, in 2016 “Pallavi Darbar” concert on advanced Pallavis (Dvinadai, Dviraga, Ettu-kalai, Chanda-taalam pallavis), with Gayathri Girish, Amritha Murali, Nisha Rajagopal, for Carnatica and Parthasarathy Swamy Sabha Performance in the Akashvani Sangeet Sammelan 2012 Regular performances in Nada Nirajanam of Sri Venkateswara Bhakti Channel (SVBC), Tirupati Performances in various TV channels such as Podhigai TV, Jaya TV, Pudu Yugam etc. Thematic programs and lecture-demonstrations such as Prahlada Bhakti Vijayam, Nauka Charitram, Sri Krishna Leela Tarangini, Raganubhava series (Carnatica Archival Centre) etc. Musical Tutelage Intensive training in gurukula style, from Sangita Kala Acharya Smt. Seetha Rajan from 1994 – 2014 Presently undergoing advanced training, under Sangita Kalanidhi Smt. -

Nishanth Chandran August 3, 2021 Principal Researcher, Microsoft Research, India

Nishanth Chandran August 3, 2021 Principal Researcher, Microsoft Research, India. Email: [email protected] \VIGYAN", No. 9, Lavelle Road, Ph: +91-80-6658 6252 Bangalore, India 560001 https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/people/nichandr/ Work Experience Microsoft Research Bangalore, India Principal Researcher July 2019 − Present Microsoft Research Bangalore, India Researcher November 2013 − July 2019 AT&T Labs − Security Research Center New York, NY Senior Member of Technical Staff October 2012 − November 2013 Microsoft Research Redmond, WA Post-doctoral Researcher July 2011 − September 2012 Research Expertise Cryptography, Cloud Security, Confidential Computing, Blockchain Computing on encrypted data, Secure Computation, Data protection and key management Education University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA Ph.D. Computer Science 2007 − 2011 { Thesis: Theoretical Foundations of Position-based Cryptography University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA M.S. Computer Science 2005 − 2007 { GPA: 4:0=4:0 Anna University (Hindustan College of Engineering) Chennai, India B.E. Computer Science and Engineering 2001 − 2005 In Media Work on Secure Neural Network Inference and Training covered by 1. \Announcing SecureNN in tf-encrypted", Ben DeCoste, December 13 2018; Web: https: //medium.com/dropoutlabs/announcing-securenn-in-tf-encrypted-9c9c3e8a5a52. 2. \A Path to Sub-Second, Encrypted Skin Cancer Detection", Yann Dupis, June 13 2019; Web: https://medium.com/dropoutlabs/encrypted-skin-cancer-detection-3d096d3b7237. Work on position-based cryptography covered by 1. Nature : \Quantum information: The conundrum of secure positioning", Gilles Brassard; Nature, 479, Pages 307-308, 2011. 2. The MIT Technology Review: \Physicists Use Location To Guarantee Security of Quantum Messages", May 13, 2010. -

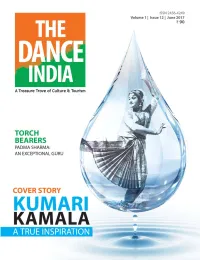

June 2017.Pmd

Torch Bearers Padma Sharma: CONTENTSCONTENTS An Exceptional Guru Cover 10 18 Story Rays of Kumari Kamala: 34 Hope A True Inspiration Dr Dwaram Tyagaraj: A Musician with a Big Heart Cultural Beyond RaysBulletin of Hope Borders The Thread of • Expressions34 of Continuity06 Love by Sri Krishna - Viraha Reviews • Jai Ho Russia! Reports • 4th Debadhara 52 Dance Festival • 5 Art Forms under One Roof 58 • 'Bodhisattva' steals the show • Resonating Naatya Tarang • Promoting Unity, Peace and Indian Culture • Tyagaraja's In Sight 250th Jayanthi • Simhapuri Dance Festival: A Celebrations Classical Feast • Odissi Workshop with Guru Debi Basu 42 64 • The Art of Journalistic Writing Tributes Beacons of light Frozen Mandakini Trivedi: -in-Time An Artiste Rooted in 63 Yogic Principles 28 61 ‘The Dance India’- a monthly cultural magazine in "If the art is poor, English is our humble attempt to capture the spirit and culture of art in all its diversity. the nation is sick." Editor-in-Chief International Coordinators BR Vikram Kumar Haimanti Basu, Tennessee Executive Editor Mallika Jayanti, Nebrasaka Paul Spurgeon Nicodemus Associate Editor Coordinators RMK Sharma (News, Advertisements & Subscriptions) Editorial Advisor Sai Venkatesh, Karnataka B Ratan Raju Kashmira Trivedi, Thane Alaknanda, Noida Contributions by Lakshmi Thomas, Chennai Padma Shri Sunil Kothari (Cultural Critic) Parinithi Gopal, Sagar Avinash Pasricha (Photographer) PSB Nambiar Sooryavamsham, Kerala Administration Manager Anurekha Gosh, Kolkata KV Lakshmi GV Chari, New Delhi Dr. Kshithija Barve, Goa and Kolhapur Circulation Manager V Srinivas Technical Advise and Graphic Design Communications Incharge K Bhanuji Rao Articles may be submitted for possible publication in the magazine in the following manner. -

Final Senior Fellowship Report

FINAL SENIOR FELLOWSHIP REPORT NAME OF THE FIELD: DANCE AND DANCE MUSIC SUB FIELD: MANIPURI FILE NO : CCRT/SF – 3/106/2015 A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF TWO VAISHNAVISM INFLUENCED CLASSICAL DANCE FORM, SATRIYA AND MANIPURI, FROM THE NORTH EAST INDIA NAME : REKHA TALUKDAR KALITA VILL – SARPARA. PO – SARPARA. PS- PALASBARI (MIRZA) DIST – KAMRUP (ASSAM) PIN NO _ 781122 MOBILE NO – 9854491051 0 HISTORY OF SATRIYA AND MANIPURI DANCE Satrya Dance: To know the history of Satriya dance firstly we have to mention that it is a unique and completely self creation of the great Guru Mahapurusha Shri Shankardeva. Shri Shankardeva was a polymath, a saint, scholar, great poet, play Wright, social-religious reformer and a figure of importance in cultural and religious history of Assam and India. In the 15th and 16th century, the founder of Nava Vaishnavism Mahapurusha Shri Shankardeva created the beautiful dance form which is used in the act called the Ankiya Bhaona. 1 Today it is recognised as a prime Indian classical dance like the Bharatnatyam, Odishi, and Kathak etc. According to the Natya Shastra, and Abhinaya Darpan it is found that before Shankardeva's time i.e. in the 2nd century BC. Some traditional dances were performed in ancient Assam. Again in the Kalika Purana, which was written in the 11th century, we found that in that time also there were uses of songs, musical instruments and dance along with Mudras of 108 types. Those Mudras are used in the Ojha Pali dance and Satriya dance later as the “Nritya“ and “Nritya hasta”. Besides, we found proof that in the temples of ancient Assam, there were use of “Nati” and “Devadashi Nritya” to please God. -

Online Film Festival Raytoday by Films Division

A Report Films Division Govt. of India, Min. of I & B, 24- Dr. G Deshmukh Marg, Mumbai -26 Dated the 10th May, 2021 Online Film Festival RayToday by Films Division Satyajit Ray, one of the greatest film makers of all the time, is credited with taking Indian cinema to the global level. A true renaissance man, Ray earned worldwide fame for himself and to the art of cinema as well, with his poetic realism and cinematic imagination. Films Division marked beginning of the year-long birth centenary celebrations of the legendary filmmaker by screening Shyam Benegal’s eponymous biopic, Satyajit Ray on 2nd May 2021 on its website. Continuing with the celebrations of the auteur, Films Division has organized an online film festival, RayToday, a curated package of non-feature works by Ray along with films on him and his oeuvre, on FD website from 7th to 9th May 2021. RayToday included, among others, a rare documentary made by him on Nobel laureate, Rabindranath Tagore, the one and only television film by Ray on a short story by Munshi Premchand and the much acclaimed biopic by Shyam Benegal. The following films werestreamed in the festival : Sadgati (Satyajit Ray/Doordarshan/52 Mins/1981) - a television film set on rural India which throws light on caste system in society. Two (Satyajit Ray/Esso World Theatre/15 Mins/1964) - a simple but hard hitting societal commentary on the class struggle shows an encounter between a child of a rich family and a street child, and displays attempts of one-upmanship between kids in their successive display of toys. -

Folk Dances of North India: an Overview K

Academic Journal of Dance and Music Xournals Xournals Academic Journal of Dance and Music ISSN UA | Volume 01 | Issue 01 | January-2019 Folk Dances of North India: An Overview K. Kabatas1 Available online at: www.xournals.com Received 12th September 2018 | Revised 11th October 2018 | Accepted 7th December 2018 Abstract: Folk dance demonstrates the nation's temperament, art, culture, simplicity, social status and customs. In simple language folk dances are the nation’s mirror. The folk dancers are represented by basic folks commonly of a specific community. These are the dances performed by the whole village community by the young and the old. Traditional folk dances has a role in preserving traditional values and teaching it to next. Folk dance are performed spontaneously with great ease and grace. Every individual region and state suggest a unique glimpse and taste into its system of life, and related traditions and rituals. The number of folk dances of India is very large so here we explore some main folk dances of north India. Most of the north Indian dances are traditional or folk dances, which marks the celebration of festivals, marriages ceremonies, celebration of birth, and the harvesting time. The present paper aims to explore the popular folk dances of North India by studying the present status of the dancing community. Keywords: Dance, Folk, India, Customs Authors: 1. Kastamonu University, Kastamonu, TURKEY. Volume 01 | Issue 01 | January-2019 | Page 5 of 9 Xournals Academic Journal of Dance and Music Introduction Hence in general the folk dance are basically shows In India, dance is considered as widely spread no thoughtful emphasis on representing the art of the activity which include their different forms and dance to the audience as they itself present in the manner. -

Chapter 1 Uday Shankar and Locating Modernity

CHAPTER 1 UDAY SHANKAR AND LOCATING MODERNITY In 1920, a twenty year old, handsome Indian student arrived in London to study painting at the Royal College of Art. Three years later, he made his debut at Covent Garden alongside the legendary Russian ballet dancer, Anna Pavlova, although—quite remarkably—until a few months earlier, he had little to no dance experience. His audiences in England, France, and the United States nevertheless thought he was very talented at what he did. The dancer invented a new style of dance, which purportedly represented Indian culture; his dance looked “foreign” enough that nobody doubted his claim. In the late 1920s, the dancer returned to India, and demonstrated his new style to his fellow compatriots. Most of his compatriots did not care for this new style, but a few prominent figures encouraged him to continue with what he was doing. His family and friends also supported him; some of them even joined his dance troupe as dancers and musicians, including his youngest brother, twenty years his junior. The troupe then returned to Paris. Meanwhile, India was nearing the end of its dramatic transition from a British imperial colony to a newly independent nation. When the dancer returned to settle in India in the late 1930s, he immersed himself in the current debates over India’s future identity and culture. Most people, who believed the essence of Indian culture could be found in its ancient traditions, were looking to the past for the “real” definition of national culture and identity. The dancer, however, proposed that his invented style and eclectic approach to art defined India’s culture instead. -

Arts-Integrated Learning

ARTS-INTEGRATED LEARNING THE FUTURE OF CREATIVE AND JOYFUL PEDAGOGY The NCF 2005 states, ”Aesthetic sensibility and experience being the prime sites of the growing child’s creativity, we must bring the arts squarely into the domain of the curricular, infusing them in all areas of learning while giving them an identity of their own at relevant stages. If we are to retain our unique cultural identity in all its diversity and richness, we need to integrate art education in the formal schooling of our students for helping them to apply art-based enquiry, investigation and exploration, critical thinking and creativity for a deeper understanding of the concepts/topics. This integration broadens the mind of the student and enables her / him to see the multi- disciplinary links between subjects/topics/real life. Art Education will continue to be an integral part of the curriculum, as a co-scholastic area and shall be mandatory for Classes I to X. Please find attached the rich cultural heritage of India and its cultural diversity in a tabular form for reading purpose. The young generation need to be aware of this aspect of our country which will enable them to participate in Heritage Quiz under the aegis of CBSE. TRADITIONAL TRADITIONAL DANCES FAIRS & FESTIVALS ART FORMS STATES & UTS DRESS FOOD (ILLUSTRATIVE) (ILLUSTRATIVE) (ILLUSTRATIVE) (ILLUSTRATIVE) (ILLUSTRATIVE) Kuchipudi, Burrakatha, Tirupati Veerannatyam, Brahmotsavam, Dhoti and kurta Kalamkari painting, Pootha Remus Andhra Butlabommalu, Lumbini Maha Saree, Langa Nirmal Paintings, Gongura Pradesh Dappu, Tappet Gullu, Shivratri, Makar Voni, petticoat, Cherial Pachadi Lambadi, Banalu, Sankranti, Pongal, Lambadies Dhimsa, Kolattam Ugadi Skullcap, which is decorated with Weaving, carpet War dances of laces and fringes.