Iskogen #0 Yule

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Ethnographic Inquiry of a Coven of Contemporary Witches James Albert Whyte Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1981 An examen of Witches: an ethnographic inquiry of a coven of contemporary Witches James Albert Whyte Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Anthropology Commons, New Religious Movements Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Whyte, James Albert, "An examen of Witches: an ethnographic inquiry of a coven of contemporary Witches" (1981). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16917. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16917 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An examen of Witches: An ethnographic inquiry of a coven of contemporary Witches by James Albert Whyte A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department: Sociology and Anthropology Maj or: Anthropology Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1981 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 WITCHCRAFT 10 WITCHES 23 AN EVENING WITH THE WITCHES 39 COVEN ORGANIZATION 55 STRESS AND TENSION IN THE SWORD COVEN 78 THE WITCHES' DANCE 92 LITERATURE CITED 105 1 INTRODUCTION The witch is a familiar figure in the popular Western imagination. From the wicked queen of Snow White to Star Wars' Yoda, witches and Witch like characters have been used to scare and entertain generations of young and old alike. -

10 June 1954 CORRIGENDA to the CONSOLIDATED SCHEDULES 1. There Is Herewith Circulated to Each Contracting Party a Draft of the C

10 June 1954 CORRIGENDA TO THE CONSOLIDATED SCHEDULES 1. There is herewith circulated to each contracting party a draft of the corrections to be made to the Consolidated Schedules in order to keep them abreast of the legal texts annexed to the General Agreement. 2. It has not been thought necessary to prepare a new page for every change. This procedure would have entailed the risk of introducing further errors. In the case of the Schedule of the Belgian Congo and Ruanda Urundi (Schedule II, Section B), however, where the whole Section has been modified, a new Section has been prepared to replace the original. 3. Accordingly, there has been prepared for each consolidated schedule which requires amendment - as listed overleaf - (i) the items which have been modified or which require substantial amendment and the new items which are to be inserted, (the texts reproduced are to replace the whole of the corresponding items or sub-items in the Consolidated Schedules, unless otherwise indicated), and (ii) a list of alterations, such as changes in punctuation marks or item numbers, deletions of items, changes of single words, etc., which can be made more quickly and conveniently by hand. 4. For changes which arise out of rectifications or modifications contained in protocols, documents, etc., the source can be conveniently traced through the "List of Changes effected by Protocols and Decisions of the CONTRACTING PARTIES" (G/75). 5. Contracting parties are requested to examine the draft and to report any additions, corrections, etc., by 10 July 1954. By that date all contracting parties should indicate the number of photo-offset copies re^ulred-.- M3T/11/54 TABLE OF CONTENTS iÈSS. -

The Witch-Cult in Western Europe, by Margaret Alice Murray This Ebook Is for the Use of Anyone Anywhere at No Cost and with Almost No Restrictions Whatsoever

20411-0 The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Witch-cult in Western Europe, by Margaret Alice Murray This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Witch-cult in Western Europe A Study in Anthropology Author: Margaret Alice Murray Release Date: January 22, 2007 [EBook #20411] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WITCH-CULT IN WESTERN EUROPE *** Produced by Michael Ciesielski, Irma THE WITCH-CULT IN WESTERN EUROPE _A Study in Anthropology_ BY MARGARET ALICE MURRAY OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS 1921 Oxford University Press _London Edinburgh Glasgow Copenhagen New York Toronto Melbourne Cape Town Bombay Calcutta Madras Shanghai_ Humphrey Milford Publisher to the UNIVERSITY PREFACE The mass of existing material on this subject is so great that I have not attempted to make a survey of the whole of European 'Witchcraft', but have confined myself to an intensive study of the cult in Great Britain. In order, however, to obtain a clearer understanding of the ritual and beliefs I have had recourse to French and Flemish sources, as the cult appears to have been the same throughout Western Europe. The New England records are unfortunately not published _in extenso_; this is the more unfortunate as the extracts already given to the public occasionally throw light on some of the English practices. -

21 CFR Ch. I (4–1–10 Edition) § 582.20

§ 582.20 21 CFR Ch. I (4–1–10 Edition) Common name Botanical name of plant source Marjoram, sweet .......................................................................... Majorana hortensis Moench. Mustard, black or brown .............................................................. Brassica nigra (L.) Koch. Mustard, brown ............................................................................ Brassica juncea (L.) Coss. Mustard, white or yellow .............................................................. Brassica hirta Moench. Nutmeg ........................................................................................ Myristica fragrans Houtt. Oregano (oreganum, Mexican oregano, Mexican sage, origan) Lippia spp. Paprika ......................................................................................... Capsicum annuum L. Parsley ......................................................................................... Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Mansf. Pepper, black ............................................................................... Piper nigrum L. Pepper, cayenne ......................................................................... Capsicum frutescens L. or Capsicum annuum L. Pepper, red .................................................................................. Do. Pepper, white ............................................................................... Piper nigrum L. Peppermint .................................................................................. Mentha piperita L. Poppy seed -

Bay Leaves - Product Specification

Bay Leaves - Product Specification PRODUCT INFORMATION Product Description The semi hand picked, dried, whole leaves of the tree Laurus nobilis L. Product Code 10BAY Ingredient Declaration Bay Leaves Flavour and Odour A delicate warm, aromatic aroma; herbal, slightly floral Appearance A light olive green oval leaf with sharp points Country of Origin Turkey PRODUCT PROFILE Particle Size 4 – 10cm Foreign Matter % <5 Moisture % <10 Total Ash % <5 Acid Insoluble Ash % <2 Volatile Oil % 1 min Pesticides & Heavy Metals Meets EU Regulations MICROBIOLOGICAL - MAXIMUM LEVELS ACCEPTED E Coli /g <100 Salmonella /25g Negative in 25g NUTRITIONAL INFORMATION / 100G Energy kcals 313 Energy kJ 1312 Protein (g) 7.61 Fat (g) 8.36 {saturates_label} 2.28 Carbohydrate (g) 74.94 Fibre (g) 26.3 Sodium (mg) 23 Salt (g) 0.0575 Version: 1 Date: 14/05/2018 www.justingredients.co.uk trade.justingredients.co.uk [email protected] [email protected] Page 1 of 5 Bay Leaves - Product Specification INTOLERANCE AND ALLERGEN INFORMATION Please ensure you have read our Allergen Policy statement available here. For further information about allergen handling by JustIngredients and its suppliers, please read our online guide here. Key: ✓ Indicates where a product is an allergen or where an allergen has intentionally been added to the final product. Cereal/Wheat products Nut and nut products Peanuts and products thereof Soybean and products thereof Sesame seed and products thereof Mustard and products thereof Milk and Dairy Products Products containing Sulphur -

Cytotoxic Activity of Essential Oils from Labiatae and Lauraceae Families Against in Vitro Human Tumor Models

ANTICANCER RESEARCH 27: 3293-3300 (2007) Cytotoxic Activity of Essential Oils from Labiatae and Lauraceae Families Against In Vitro Human Tumor Models MONICA ROSA LOIZZO1, ROSA TUNDIS1, FEDERICA MENICHINI1, ANTOINE MIKAEL SAAB2, GIANCARLO ANTONIO STATTI1 and FRANCESCO MENICHINI1 1Faculty of Pharmacy, Nutrition and Health Sciences, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Calabria, I-87036 Rende (CS), Italy; 2Faculty of Sciences II, Chemistry Department, Lebanese University, P.O. Box :90656 Fanar, Beirut, Lebanon Abstract. Background: The aim of this work was to study undertaken on the cytotoxic activity of essential oils from the cytotoxicity of essential oils and their identified Sideritis perfoliata, Satureia thymbra, Salvia officinalis, Laurus constituents from Sideritis perfoliata, Satureia thymbra, nobilis or Pistacia palestina. Salvia officinalis, Laurus nobilis and Pistacia palestina. The genus Sideritis (Labiatae) is of great botanical and Materials and Methods: Essential oils were obtained by pharmacological interest, in fact many species are reported hydrodistillation and were analysed by gas chromatography to have analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, (GC) and GC/mass spectrometry (MS). The cytotoxic activity antirheumatic, anti-ulcer, digestive and vaso-protective was evaluated in amelanotic melanoma C32, renal cell properties and have been used in Mediterranean folk adenocarcinoma ACHN, hormone-dependent prostate medicine (11). No reports have been found concerning the carcinoma LNCaP, and MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines by phytochemical composition or biological or cytotoxic activity the sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay. Results: L. nobilis fruit of S. perfoliata (12). S. thymbra (Labiatae) is the most oil exerted the highest activity with IC50 values on C32 and common Satureja specimen and is known as a herbal home ACHN of 75.45 and 78.24 Ìg/ml, respectively. -

Umi-Uta-1189.Pdf (299.6Kb)

PARTICIPATION, IDENTITY, AND SOCIAL SUPPORT IN A SPIRITUAL COMMUNITY by LA DORNA MCGEE Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN SOCIOLOGY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON December 2005 Copyright © by La Dorna McGee 2005 All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my mom who always supported me in my endeavors. I would also like to thank Kathy Rowe, Jane Nicol, and Suzanne Baldon for their support. Lastly, I would like to thank my committee members for their extreme patience and guidance through this process. April 22, 2005 iii ABSTRACT PARTICIPATION, IDENTITY, AND SOCIAL SUPPORT IN A SPIRITUAL COMMUNITY Publication No. ______ La Dorna McGee, M.A. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2005 Supervising Professor: Frank Weed Paganism is a loosely organized community whose religious ideology incorporates the immanence of Deity. As a religious association with an ideology different from traditional Judeo-Christian faiths, members are often labeled as deviant and subjected to various negative sanctions. By relying on survey data collected on April 9-12, 1996 and in depth personal interviews collected on October 10-13, 1996, this study presents a model that best describes and explains acceptance and participation in Pagan spiritualism. This study identifies three characteristics associated with positive ratings of childhood religious affiliation (church disaffection, family closeness, and iv membership role), three characteristics associated with feelings of belonging to the Pagan community (church disaffection, social support, and participation), and finally examines a member’s disclosure of their Pagan identity as being a function of occupational prestige, weighing the costs of negative sanctions versus the Pagan value of openly expressing a Pagan identity, and self-efficacy. -

Grimoire of Eclectic Magick (

1 of 3 Grimoire of eclectic Magick Part ( Permission is given for the distribution of this text in electronic form, with these conditions: s No fees may be charged for the distribution or transmission of this document, other than standard charges for use of transmiss ion lines or electronic media. Distribution for commercial purposes or by commercial entities is specifically prohibited. s All copies distributed must contain the complete, unedited text of the original document and this copyright notice. s Persons acquiring this electronic version of the document can make one (1) printed copy for their own personal use. All other rights are retained by the author Typography . Cover Graphics FLA Millennium, Shannon Teague Alchemist, Computer Safari Text Alchemy, Cosmorama Enterprises Copyright © Beltain 2000 by Parker Torrence. Fifties, WSI-Font Collection DF Calligraphic Ornaments LET, Garden Display Caps, WSI-Font Collection Esselte Letraset Ltd. All rights reserved, all wrongs returned Three Fold! Krone, WSI-Font Collection Genji, Emerald City Fontworks Wellsley, J. Fordyce Veve, Scriptorium Fonts Witchcraft, Typearound Font WoolBats, Curtis Clark Movie images are from http://www.spe.sony.com/movies/thecraft/ In 1996, “The Craft” was released in theaters and a G hat is Wicca? r new standard for movies about witchcraft was i established. This was in part due to the technical advice m of Pat Devin, an Elder and the first officer of the o Southern California local council of C.O.G. (Covenant i W r "Basically, Wicca is an evolving religion of theGoddess) established in California in 1975, an e incorporated, religious, non-profit organization. -

Surviving and Thriving in a Hostile Religious Culture Michelle Mitchell Florida International University, [email protected]

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 11-14-2014 Surviving and Thriving in a Hostile Religious Culture Michelle Mitchell Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI14110747 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the New Religious Movements Commons Recommended Citation Mitchell, Michelle, "Surviving and Thriving in a Hostile Religious Culture" (2014). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1639. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1639 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida SURVIVING AND THRIVING IN A HOSTILE RELIGIOUS CULTURE: CASE STUDY OF A GARDNERIAN WICCAN COMMUNITY A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in RELIGIOUS STUDIES by Michelle Irene Mitchell 2014 To: Interim Dean Michael R. Heithaus College of Arts and Sciences This thesis, written by Michelle Irene Mitchell, and entitled Surviving and Thriving in a Hostile Religious Culture: Case Study of a Gardnerian Wiccan Community, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Lesley Northup _______________________________________ Dennis Wiedman _______________________________________ Whitney A. Bauman, Major Professor Date of Defense: November 14, 2014 The thesis of Michelle Irene Mitchell is approved. -

Coffee Table Coven Magazine

CoffeeTable Coven Issue 08 CoffeeTable CovenIssue 08/March 2019 Spotlight on: Stephen @awitchespath The Eostre Sabbat Holi & Ostara: Joining Celebrations Menstrual Magic & many more articles inside! 1 CoffeeTable Coven Issue 08 Featured Artist: Ahnalisa Reavis [email protected] Instagram: dirtworks_ceramics Facebook: www.facebook.com/dirtworksceramics Website: www.dirtworksceramics.com 2 3 CoffeeTable Coven Issue 08 IG: @cinnamonhare 4 5 CoffeeTable Coven Issue 08 TABLE OF CONTENTS Astrological Forecast Page 8 March's Crystal & Herbal Feature Page 38 Astronomy Reference Guide Page 12 Menstrual Magic Page 44 Editorial Letter Page 14 Spotlight On: Stephen Page 50 InstaFeature: @covenofcrows Page 18 Ostara Lavender Lemonade Recipe Page 58 Spring Fae by S.K. Tom Yick Page 22 Ostara Tarot Spread Page 62 The Eostre Sabbat Page 24 Ostara Blessings: A Short Story Page 68 Holi & Ostara: Joining Celebrations Page 30 Element by Sam Grey Page 74 6 7 CoffeeTable Coven Issue 08 horoscope predicts that although within. March's Astrological this month of march 2019 is a balancing act for you, there is Capricorn (Dec. 21 – Jan. 19) Forecast much to learn and receive in the Everyone deserves a break now reflection of another’s life. and then. The only problem, https://www.yearly-horoscope.org/march-2019-monthly/ Capricorn, is you may continue to Libra (Sept. 22 – Oct. 23) Aries (March 20-Apr. 19) be tapped through your strong run the treadmill. You are running in different Your ability to take the lead communication skills. If so, you can miss the opportunity and push through obstacles is directions this month trying to keep for sweet reflection that leads to a your world in balance. -

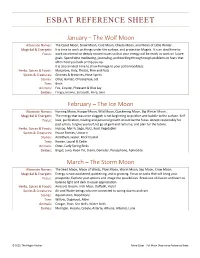

Esbat Reference Sheet

ESBAT REFERENCE SHEET January – The Wolf Moon Alternate Names: The Quiet Moon, Snow Moon, Cold Moon, Chaste Moon, and Moon of Little Winter… Magickal & Energetic It is time to work on things under the surface, and protection Magick. It is an ideal time to Focus: work on internal or deeply rooted issues so that your energy will be ready to work on future goals. Spend time meditating, journaling, and working through tough problems or fears that often hold you back or trip you up. It is also an ideal time to show homage to your patron Goddess. Herbs, Spices & Foods: Marjoram, Holy, Thistle, Pine and Nuts Spirits & Creatures: Gnomes & Brownies, Hose Spirits Stones: Onyx, Garnet, Chrysoprase, Jet Tree: Birch Animals: Fox, Coyote, Pheasant & Blue Jay Deities: Freyja, Inanna, Sarasvati, Hera, Sinn February – The Ice Moon Alternate Names: Horning Moon, Hunger Moon, Wild Moon, Quickening Moon, Big Winter Moon… Magickal & Energetic The energy that was once sluggish is not beginning to quicken and bubble to the surface. Self- Focus: love, purification, healing and personal growth should be the focus. Accept responsibly for past errors, forgive yourself, let go of guilt and remorse, and plan for the future. Herbs, Spices & Foods: Hyssop, Myrrh, Sage, Nuts, Root Vegetables Spirits & Creatures: House Faeries, Unicorn Stones: Amethyst, Jasper, Rock Crystal Tree: Rowan, Laurel & Cedar Animals: Otter, Early Spring Birds Deities: Brigid, Juno, Kuan Yin, Diana, Demeter, Persephone, Aphrodite March – The Storm Moon Alternate Names: The Seed Moon, Moon of Winds, Plow Moon, Worm Moon, Sap Moon, Crow Moon… Magickal & Energetic Energy is now awakened, quickening, and is growing. -

21 CFR Ch. I (4–1–17 Edition) § 182.20

§ 182.20 21 CFR Ch. I (4–1–17 Edition) Common name Botanical name of plant source Marigold, pot ........................................................... Calendula officinalis L. Marjoram, pot .......................................................... Majorana onites (L.) Benth. Marjoram, sweet ...................................................... Majorana hortensis Moench. Mustard, black or brown ......................................... Brassica nigra (L.) Koch. Mustard, brown ....................................................... Brassica juncea (L.) Coss. Mustard, white or yellow ......................................... Brassica hirta Moench. Nutmeg .................................................................... Myristica fragrans Houtt. Oregano (oreganum, Mexican oregano, Mexican Lippia spp. sage, origan). Paprika .................................................................... Capsicum annuum L. Parsley .................................................................... Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Mansf. Pepper, black .......................................................... Piper nigrum L. Pepper, cayenne ..................................................... Capsicum frutescens L. or Capsicum annuum L. Pepper, red ............................................................. Do. Pepper, white .......................................................... Piper nigrum L. Peppermint .............................................................. Mentha piperita L. Poppy seed ............................................................