Healing Lessons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

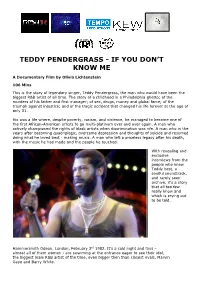

Teddy Pendergrass - If You Don’T Know Me

TEDDY PENDERGRASS - IF YOU DON’T KNOW ME A Documentary Film by Olivia Lichtenstein 106 Mins This is the story of legendary singer, Teddy Pendergrass, the man who would have been the biggest R&B artist of all time. The story of a childhood in a Philadelphia ghetto; of the murders of his father and first manager; of sex, drugs, money and global fame; of the triumph against injustice; and of the tragic accident that changed his life forever at the age of only 31. His was a life where, despite poverty, racism, and violence, he managed to become one of the first African-American artists to go multi-platinum over and over again. A man who actively championed the rights of black artists when discrimination was rife. A man who in the years after becoming quadriplegic, overcame depression and thoughts of suicide and resumed doing what he loved best - making music. A man who left a priceless legacy after his death, with the music he had made and the people he touched. With revealing and exclusive interviews from the people who knew Teddy best, a soulful soundtrack, and rarely seen archive, it’s a story that all too few really know and which is crying out to be told… Hammersmith Odeon, London, February 3rd 1982. It’s a cold night and fans – almost all of them women - are swarming at the entrance eager to see their idol, the biggest male R&B artist of the time, even bigger then than closest rivals, Marvin Gaye and Barry White. Teddy Pendergrass – the Teddy Bear, the ‘Black Elvis’ - tall and handsome with a distinctive husky soulful voice that could melt a woman’s clothes clean off her body! 'It took Teddy eleven seconds to get to the point with a girl that would take me two dinners and a trip to meet her parents,' says Daniel Markus, one of his managers. -

Mental Effort from an Lpcomin Disco Sound on This Energetic T, "MY

3, 1979 $2.25 SINGLES SLEEPERS THE WHO, "LONG LIVE ROCK" (prod. not LOUISIANA'S LE ROU listed) (writer: Peter Townshend) by L. S. Me MCA (Towser Tunes, BMI) (3:58).Ini- Pollard) RECORDStially released on their "Odds & Lemed, Sods" Ip, this comes roaring out chapter #00001"Ist "The Kids Are Alright 'sound- rock is vg trackandaptlycapturesthe one isfire theme behind one of rock's leg- blues - rock ends. MCA 41053 tempo shades.. HOT CHOCOLATE, "GOING THROUGH PHILLY CREAM, "MO THE MOTIONS" (prod by M. (prod by Barry- ri Most) (writer: E. Brown) (Finch - Barry -Ingram)(P ry serv.. ley, ASCAP) (3:54). Vocal, string BMI)(3:59).Greatead v re-mixa:] and synthesizer intensity build to trades and brilliant horns to .ontami 4a dramatic climax on this monu- disco sound on thisenergetic ostfamilsir mental effort from an Lpcomin disc. Splendid arrangement/pro- a staid -out and 1p A multi -format smash. Infinity duction give this widespread ap- the rri should 50,016. I. Fantasy/WMOT 862 110 12. THE Cane PATTI SMITH GROUP, "FREDERICK" T, "MY LOVE is" (prod by TH AR V-0. ou p CANDY -11 (prod by T. Rundigren) (writer: P t)(writers: rWright-McCray) was on andful reak Smith)(Ninja,' tASCAFT) (3:01 Iyn.BMI /DErnbet,BMI) (5:48). through t"f, dominan Smith's urgent Vocals, encas it'sfinestefforttodate summer an by ringing guitars, plead the m dikes the most of her grandiose duced by Roy Thomas sage while keyboard lines iz vocaltalentPrecision back-up tinues their esoteric roc of zle. Rundgren produces w chorals, prominent piano Imes & view. -

Representations and Discourses of Black Motherhood in Hip Hop and REPRESENTATIONS and DISCOURSES

Chaney and Brown: Representations and Discourses of Black Motherhood in Hip Hop and REPRESENTATIONS AND DISCOURSES . Representations and Discourses of Black Motherhood in Hip Hop and R&B over Time Cassandra Chaney and Arielle Brown This study will examine how representations and discourses regarding Black motherhood have changed in the Hip Hop and R&B genres over time. Specifically, this scholarly work will contextualize the lyrics of 79 songs (57 Hip Hop songs; 18 R&B songs; 2 songs represented the Hip Hop and R&B genre; 2 songs represented artists who produce music in 5 or 6 genres) from 1961-2015 to identify the ways that Black male and Black female artists described motherhood. Through the use of Black Feminist Theory, and by placing the production of these songs within a sociohistorical context, we provide an in-depth qualitative examination of song lyrics related to Black motherhood. Results gave evidence that representations and discourse of motherhood have been largely shaped by patriarchy as well as cultural, political, and racial politics whose primary aim was to decrease the amount of public support for poor, single Black mothers. In spite of the pathological framing of Black mothers, most notably through the “welfare queen” and “baby mama” stereotypes, a substantial number of Hip Hop and R&B artists have provided a strong counter narrative to Black motherhood by highlighting their positive qualities, acknowledging their individual and collective struggle, and demanding that these women be respected. How has patriarchy influenced the production and release of Hip Hop and R&B songs related to Black motherhood? In what ways has Hip Hop and R&B supported and challenged dominant representations and discourses surrounding Black 1 motherhood? How has Black Feminist Theory validated the experiences of Black mothers in Hip Hop and R&B? This manuscript will respond to these three questions by examining how societal changes have directly influenced how Black mothers in Hip Hop and R&B2 are intellectualized. -

"A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 Piano Solo | Twelfth 12Th Street Rag 1914 Euday L

Box Title Year Lyricist if known Composer if known Creator3 Notes # "A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 piano solo | Twelfth 12th Street Rag 1914 Euday L. Bowman Street Rag 1 3rd Man Theme, The (The Harry Lime piano solo | The Theme) 1949 Anton Karas Third Man 1 A, E, I, O, U: The Dance Step Language Song 1937 Louis Vecchio 1 Aba Daba Honeymoon, The 1914 Arthur Fields Walter Donovan 1 Abide With Me 1901 John Wiegand 1 Abilene 1963 John D. Loudermilk Lester Brown 1 About a Quarter to Nine 1935 Al Dubin Harry Warren 1 About Face 1948 Sam Lerner Gerald Marks 1 Abraham 1931 Bob MacGimsey 1 Abraham 1942 Irving Berlin 1 Abraham, Martin and John 1968 Dick Holler 1 Absence Makes the Heart Grow Fonder (For Somebody Else) 1929 Lewis Harry Warren Young 1 Absent 1927 John W. Metcalf 1 Acabaste! (Bolero-Son) 1944 Al Stewart Anselmo Sacasas Castro Valencia Jose Pafumy 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Accidents Will Happen 1950 Johnny Burke James Van Huesen 1 According to the Moonlight 1935 Jack Yellen Joseph Meyer Herb Magidson 1 Ace In the Hole, The 1909 James Dempsey George Mitchell 1 Acquaint Now Thyself With Him 1960 Michael Head 1 Acres of Diamonds 1959 Arthur Smith 1 Across the Alley From the Alamo 1947 Joe Greene 1 Across the Blue Aegean Sea 1935 Anna Moody Gena Branscombe 1 Across the Bridge of Dreams 1927 Gus Kahn Joe Burke 1 Across the Wide Missouri (A-Roll A-Roll A-Ree) 1951 Ervin Drake Jimmy Shirl 1 Adele 1913 Paul Herve Jean Briquet Edward Paulton Adolph Philipp 1 Adeste Fideles (Portuguese Hymn) 1901 Jas. -

TEDDY. You Know How Much That Name Means

TEDDY. You know how much that name means. His new hit single, "Turn Off the Lights',' is only the beginning of another feverish season of airplay, appearances and sales action. The new Teddy Pendergrass album. Justsay "Teddy:' It's a beautiful sound. Shipped gold on Philadelphia International Records and Tapes. Distributed by CBS Records. TEDDY PENDERGRASS 1979 TOUR 6/1-2 Sacramento, CA Memorial Auditorium 6/3 Pasadena, CA Civic Arena 6/8 San Diego, CA San Diego Stadium 6/10 Fresno, CA Convention Center 6/14 Minneapolis, MN Northrope Auditorium 6/15 Omaha, NE Civic Center 6/16 Tulsa, OK Assembly Civic Center 6/17 Norman, OK Lloyd Noble Civic Center 6/21 Denver, CO Red Rocks 6/22 Kansas City, MO Kansas City Stadium 6/23 Cincinnati, OH Riverfront Coliseum 6/24-25 Detroit, MI Pine Knob Pavilion 6/27 New York City, NY Madison Square Garden 6/29 Charlotte, NC Coliseum 6/30 Savannah, GA Civic Center 7/1 Tampa, FL Curtis Hixon Convention Hall 7/3-8 Fort Lauderdale, FL Sunrise Theatre 7/11-12 Greenville, SC Memorial Auditorium 7/13 Greensboro, NC Coliseum 7/14 Columbia, SC Carolina Coliseum 7/15 Atlanta. GA Omni 7/19 Indianapolis, IN Convention Center 7/20 Milwaukee, WI Mecca 7/21 Chicago, IL Comiskey Park 7/22 Saginaw, MI Weller Arena 7/26 Philadelphia, PA Spectrum 7/27 Pittsburgh, PA Civic Arena 7/28 Cleveland, OH Richfield Coliseum 7/29 Baltimore, MD Civic Center 8/2 Beaumont, TX Civic Center 8/3 Shreveport, LA Hirsch Memorial Coliseum 8/4 Pine Bluff, AR Convention Center 8/5 St. -

4-Year Song History

SONGFEST 2020 Four Year Song History Competing Songfest groups may not perform any songs that have appeared in Songfest during the previous four years. It should also be noted that just because a song may not have appeared in Songfest in the past four years does NOT mean that that the Songfest staff will allow it to be used in the show. SONGFEST 2016 Song Title Composer(s) and/or Lyricist(s) Cabin Fever Cynthia Weil, Barry Mann Can’t Help Falling in Love Hugo Peretti, Luigi Creatore, George David Weiss Dancing in the Moonlight Sherman Kelly Discombobulate Hans Zimmer Give Your Heart a Break Josh Alexander, Billy Steinberg Go to the Mardi Gras Tee Terry, Henry Roeland Byrd Go Your Own Way Lindsay Buckingham God Bless Us Everyone Alan Silvestri, Glen Ballard Going Home Antonín Dvořák, William Arms Fisher The Government Can Leslie Bricusse, Anthony Newley, Tim Hawkins Halo Ryan Tedder, Evan Bogart, Beyoncé Knowles Help! John Lennon Holiday Chris Stivers I Feel the Earth Move Carole King I Got You Tom Kitt, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Amanda Green Kids in America Rickey Wilde, Marty Wilde Know Your Enemy Billy Joe Armstrong, Mike Dirnt, Frank Wright Let’s Groove Wayne Vaughn, Maurice White Man in the Mirror Siedah Garrett, Glen Ballard Masquerade Andrew Lloyd Webber Me and My Shadow Billy Rose, Al Jolson, Dave Dreyer One Night Only Henry Krieger, Tom Eyen Pi Chris Hardwick, Mike Phirman A Place in the Choir Bill Staines Radioactive Melvyn Gonzalez, Alexander Grant, Ben McKee, Josh Mosser, Dan Platzman, Dan Reynolds, Wayne Sermon Raise Your Voice -

Key-Notes Issue#159.Pub

FEBRUARY 2007 ISSUE #159 Inside: Now, Ladies & Gents Club Services Thanks For the Music Group/Solo Effort RAMBLINGS FROM THE EDITOR VIEW FROM THE TOP Congratulations to the 2007 office team you elected to run your club. They include: Bill Donohue, President; Les Knier, Vice President; Erna Welcome to another year of Reinhart, Secretary and Charlie collecting with the Keystone Record Collectors! Reinhart, Treasurer. I want to thank all elected and appointed officers They are all committed to do the best they can for you, for their commitment to the club for 2006. A however, they can’t do it all alone. Volunteer your time, expertise, comments and knowledge. Please help them special thank you to the officers who stepped up make our club and show even more effective. and performed double duty while I had some personal items to take care of. Thank you to all At the January Business meeting, following the announcement of the election results, all of the current members for their votes of support for the 2007 appointed officers were reappointed for 2007. They include: officer team and myself. Steve Yohe, Show Coordinator; Bob “Will” Williams, Site Coordinator; Doug Smith, Phone Reservations; Phil As you know, we are changing vendor table size Schwartz, Special Projects Coordinator, Les Knier, Web from 6 foot to 8 foot, allowing for what we thank Site Coordinator, Ron Diehl, Club Photographer, B. Derek will be a more efficient operation. This brings up Shaw, Newsletter and Communications and Dave Schmidt, another situation that we need to take into newly named Show Flyer Guru. -

Journal of Hip Hop Studies

et al.: Journal of Hip Hop Studies June 2016 Published by VCU Scholars Compass, 2016 1 Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Vol. 3 [2016], Iss. 1, Art. 1 Editor in Chief: Daniel White Hodge, North Park University Senior Editorial Advisory Board: Anthony Pinn, Rice University James Paterson, Lehigh University Book Review Editor: Gabriel B. Tait, Arkansas State University Associate Editors: Cassandra Chaney, Louisiana State University Jeffrey L. Coleman, St. Mary’s College of Maryland Monica Miller, Lehigh University Associate & Copy Editor: Travis Harris, PhD Student, College of William and Mary Editorial Board: Dr. Rachelle Ankney, North Park University Dr. Jason J. Campbell, Nova Southeastern University Dr. Jim Dekker, Cornerstone University Ms. Martha Diaz, New York University Mr. Earle Fisher, Rhodes College/Abyssinian Baptist Church, United States Dr. Daymond Glenn, Warner Pacific College Dr. Deshonna Collier-Goubil, Biola University Dr. Kamasi Hill, Interdenominational Theological Center Dr. Andre E. Johnson, University of Memphis Dr. David Leonard, Washington State University Dr. Terry Lindsay, North Park University Ms. Velda Love, North Park University Dr. Anthony J. Nocella II, Hamline University Dr. Priya Parmar, SUNY Brooklyn, New York Dr. Soong-Chan Rah, North Park University Dr. Rupert Simms, North Park University Dr. Darron Smith, University of Tennessee Health Science Center Dr. Jules Thompson, University Minnesota, Twin Cities Dr. Mary Trujillo, North Park University Dr. Edgar Tyson, Fordham University Dr. Ebony A. Utley, California State University Long Beach, United States Dr. Don C. Sawyer III, Quinnipiac University https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/jhhs/vol3/iss1/1 2 et al.: Journal of Hip Hop Studies . Sponsored By: North Park Universities Center for Youth Ministry Studies (http://www.northpark.edu/Centers/Center-for-Youth-Ministry-Studies) Save The Kids Foundation (http://savethekidsgroup.org/) Published by VCU Scholars Compass, 2016 3 Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Vol. -

Better by Continuing Rumors of Buyouts by ABC, Columbia Pictures, CBS and Traditional Folios ELECTED AGAIN: Bernie Fleischer, Now Polygram

50 General News Sound Business Buddah's Moore SAN FRANCISCO COLLEGE Visits 40 Cities NEW YORK -Hush Productions Practical Advice has planned a 40 -city U.S. tour for Buddah Records artist Melba Moore to coincide with the release of Rules This School her new album, "Portrait of Melba." By JIM KELTON Also planned are appearances on SAN FRANCISCO such tv shows as "Mery Griffin," -Leo de ever for the school, which started Gar Kulka, "Mike Douglas." "Soul Train," "Di- dean of the College with 12 students in 1974. Eight for Recording Arts in nah" and a slew of specials. the south students are working towards i of Market industrial diplomas in Hush Productions, which man- area, is ada- the advance class. mant about practicalities. There were ages Moore, is also negotiating with 18 in the group two And with good reason. a number of movie companies for He semesters ago. Kulka washed out started in the recording production and release of the movie business 10 on the basis of personal inter- in Southern California version of the Broadway musical, some 20 views. years ago with a "Purlie," in which she will re- create conspicuous Most of the students are results lack of business know -how. her Tony Award -winning lead role. Early of industry or personal referrals, on, he produced, engineered A number of tv product endorse- and but some answer ads in trade generally put together ments are also expected to help the nov- publications. Tuition costs from elty record "Pink boost sales of the LP. Shoelaces" $250 to $480 per course, depend- ;d4, which sold a million The album was produced by copies. -

Black Music: Its Message and Meaning

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1980 Volume VI: The Present as History Black Music: Its Message and Meaning Curriculum Unit 80.06.04 by Ivory Erkerd The purpose of this unit is to offer students who are in remedial reading programs a familiar medium through which they can develop an appreciation for modern black music from a historical, political and lyrical perspective while at the same time developing vocabulary, listening skills, reading comprehension and writing skills. Emphasis will be placed on the political and the historical surge of the civil rights movement of the 1960’s and how this surge directly or indirectly affected black musicians, who in turn affected the black population of America during this period. A major objective will be to integrate some of the more popular songs of the last twenty years with a study of the social and political impact of the black movement on black people. The aim is to teach students to analyze the present as history, to research, analyze, predict and translate the black movement into their own creative and artistic statements, whether musical or literary. The strategy underlying this unit grew out of my observations about the important role that music played in my students’ daily lives. For the Christmas of 1979, it seemed that many black teenagers received a portable music machine, equipped with AM-FM radio, cassette player/recorder, eight-tract tape, earphones, microphone, stereo speakers and “genuine leather” carrying straps. The in reasons for wanting these sets ranged from “I want my music with me all the time,” to “Music is my life and I want it close to me.” Black music has always been “big” with black teenagers. -

UNIS VERS« Harmonia Mundi Gmbh Zimmerstraße 68 · 10117 Berlin Tel

& jazzworld music Mathias Lévy auf Grappellis Geige »UNIS VERS« harmonia mundi gmbh Zimmerstraße 68 · 10117 Berlin Tel. 030/2062162-0 · Fax 030/2062162-10 [email protected] Foto: © Jean-Baptiste Millot VIII/2019 www.harmoniamundi.com Die aktuellen Bestseller Gianmaria Testa Tiken Jah Fakoly Prezioso Le Monde est chaud INC 267 (T01) WRA 7752357 (R01) 1 2 »Im Duett mit Soprano erreicht Fakoly auch jüngeres Publikum, The Cat Empire insgesamt ist ›Le Monde est chaud‹ eher der musikalischen Tra- Stolen Diamonds dition verpflichtet, mit gepflegten zeitlosen Arrangements.« RFI – LES VOIX DU MONDE Sara Correia WRACD 013 (P01) 3 »The Cat Empire haben ein Album veröffentlicht, das es unmög- WRA 7668213 (P01) lich macht, einfach stillzustehen und zuzuhören.« BEAT.COM 4 Leyla McCalla CAPITALI$T BLUES »… kraftvolle, charismatische Stimme, die die Intensität, Essenz und Leidenschaft des Fado vermittelt.« WORLDMUSICCENTRAL.ORG Cuarteto Sol Tango Sin Palabras JV 570154 (R01) 5 CAVI 8553424 (T01) The Art Ensemble of Chicago We Are on the Edge 6 A 50th Anniversary Celebration Hope Masike The Exorcism of a Spinster 2 CDs: PI 80 (L02) 7 »Das Art Ensemble bleibt weiterhin neugierig und uns mit die- WMN TUG 1122 (R01) sem Upgrade hoffentlich noch lange erhalten.« STEREOPLAY 8 Angelika Niescier New York Trio feat. Jonathan Finlayson Aki Takase Hokusai Piano Solo INT 321 (T01) 9 INT 327 (T01) »Dynamik und Freiheit der Musik verschlagen einem gerade 10 auch in den kontemplativen Balladen mitunter den Atem.« KÖLNER STADTANZEIGER 2 Mathias Lévy »Unis vers« Die Violine von Stéphane Grappelli Nach »Revisiting Grappelli«, einer Hommage an den großen Geiger des Jazz, Stéphane Grappelli (1908-1997), greift der Geiger Mathias Artikelnummer: HMM 902506 Lévy erneut zu der berühmten Violine des Geigenbauers Pierre Hel, Preiscode: T01 die Grappelli sein Leben lang begleitete, bevor er sie dem Musée de Kategorie: Kammermusik, Jazz la musique in Paris vermachte. -

Political Commentary in Black Popular Music from Rhythm and Blues to Early Hip Hop

MESSAGE IN THE MUSIC: POLITICAL COMMENTARY IN BLACK POPULAR MUSIC FROM RHYTHM AND BLUES TO EARLY HIP HOP James B. Stewart "Music is a powerful tool in the form of communication [that] can be used to assist in organizing communities." Gil Scott-Heron (1979) This essay examines the content of political commentaries in the lyrics of Rhythm and Blues (R & B) songs. It utilizes a broad definition of R & B that includes sub-genres such as Funk and "Psychedelic Soul." The investigation is intended, in part, to address persisting misinterpretations of the manner in which R & B influenced listeners' political engagement during the Civil Rights- Black Power Movement. The content of the messages in R & B lyrics is deconstructed to enable a fuller appreciation of how the creativity and imagery associated with the lyrics facilitated listeners' personal and collective political awareness and engagement. The broader objective of the essay is to establish a foundation for understanding the historical precedents and political implications of the music and lyrics of Hip Hop. For present purposes, political commentary is understood to consist of explicit or implicit descriptions or assessments of the social, economic, and political conditions of people of African descent, as well as the forces creating these conditions. These criteria deliberately exclude most R & B compositions because the vast majority of songs in this genre, similar to the Blues, focus on some aspect of male-female relationships.' This is not meant to imply that music examining male-female relationships is devoid of political implications; however, attention is restricted here to lyrics that address directly the relationship of African Americans to the larger American body politic.