Waking up to the Sound

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry Howard Rambsy II The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor First paperback edition 2013 Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2011 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 5432 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rambsy, Howard. The black arts enterprise and the production of African American poetry / Howard Rambsy, II. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-472-11733-8 (cloth : acid-free paper) 1. American poetry—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Poetry—Publishing—United States—History—20th century. 3. African Americans—Intellectual life—20th century. 4. African Americans in literature. I. Title. PS310.N4R35 2011 811'.509896073—dc22 2010043190 ISBN 978-0-472-03568-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12005-5 (e-book) Cover illustrations: photos of writers (1) Haki Madhubuti and (2) Askia M. Touré, Mari Evans, and Kalamu ya Salaam by Eugene B. Redmond; other images from Shutterstock.com: jazz player by Ian Tragen; African mask by Michael Wesemann; fist by Brad Collett. -

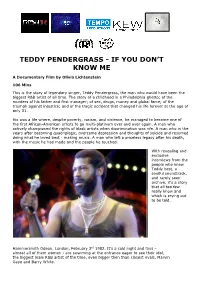

Teddy Pendergrass - If You Don’T Know Me

TEDDY PENDERGRASS - IF YOU DON’T KNOW ME A Documentary Film by Olivia Lichtenstein 106 Mins This is the story of legendary singer, Teddy Pendergrass, the man who would have been the biggest R&B artist of all time. The story of a childhood in a Philadelphia ghetto; of the murders of his father and first manager; of sex, drugs, money and global fame; of the triumph against injustice; and of the tragic accident that changed his life forever at the age of only 31. His was a life where, despite poverty, racism, and violence, he managed to become one of the first African-American artists to go multi-platinum over and over again. A man who actively championed the rights of black artists when discrimination was rife. A man who in the years after becoming quadriplegic, overcame depression and thoughts of suicide and resumed doing what he loved best - making music. A man who left a priceless legacy after his death, with the music he had made and the people he touched. With revealing and exclusive interviews from the people who knew Teddy best, a soulful soundtrack, and rarely seen archive, it’s a story that all too few really know and which is crying out to be told… Hammersmith Odeon, London, February 3rd 1982. It’s a cold night and fans – almost all of them women - are swarming at the entrance eager to see their idol, the biggest male R&B artist of the time, even bigger then than closest rivals, Marvin Gaye and Barry White. Teddy Pendergrass – the Teddy Bear, the ‘Black Elvis’ - tall and handsome with a distinctive husky soulful voice that could melt a woman’s clothes clean off her body! 'It took Teddy eleven seconds to get to the point with a girl that would take me two dinners and a trip to meet her parents,' says Daniel Markus, one of his managers. -

Harold Melvin and the Bluenotes Where Are All My Friends Mp3, Flac, Wma

Harold Melvin And The Bluenotes Where Are All My Friends mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Funk / Soul Album: Where Are All My Friends Country: US Released: 1974 Style: Soul, Disco MP3 version RAR size: 1805 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1233 mb WMA version RAR size: 1786 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 961 Other Formats: AUD AC3 MPC MMF WMA AA RA Tracklist Hide Credits Where Are All My Friends A Written By – V.Carstarphen - G.McFadden - J.WhiteheadWritten-By – G.McFadden*, 3:25 J.Whitehead*, V.Carstarphen* Let It Be You B 3:32 Written-By – K. Gamble - L. Huff* Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – CBS Inc. Manufactured By – Columbia Records Of Canada, Ltd. Recorded At – Sigma Sound Studios Mastered At – Frankford/Wayne Recording Labs Published By – Mighty Three Music Published By – World War Three Music Credits Arranged By – Bobby Martin Performer [Music By] – MFSB Producer – Gamble-Huff* Notes Mastered at Frankford/Wayne Recording Labs, Phila.,Pa. "The Sound of Philadelphia"® [A]: ℗1974 CBS Inc. [B]: ℗1972 CBS Inc. Barcode and Other Identifiers Rights Society: BMI Matrix / Runout (A side label): AA-AF ZS8-3552-3 Matrix / Runout (B side label): AA-AF ZS8-3552-4 Matrix / Runout (A side etched runout): ZS8-3552-3-1A-2H: Matrix / Runout (B side etched runout): ZS8-3552-4-1A-2H: Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Harold Melvin Philadelphia Where Are All ZS8 3552 And The International ZS8 3552 US 1974 My Friends (7") Bluenotes* Records Harold Melvin Where Are All Philadelphia S PIR 2819 And The -

Soul Top 1000

UUR 1: 14 april 9 uur JAAP 1000 Isley Brothers It’s Your Thing 999 Jacksons Enjoy Yourself 998 Eric Benet & Faith Evans Georgy Porgy 997 Delfonics Ready Or Not Here I Come 996 Janet Jackson What Have Your Done For Me Lately 995 Michelle David & The Gospel Sessions Love 994 Temptations Ain’t Too Proud To Beg 993 Alain Clark Blow Me Away 992 Patti Labelle & Michael McDonald On My Own 991 King Floyd Groove Me 990 Bill Withers Soul Shadows UUR 2: 14 april 10 uur NON-STOP 989 Michael Kiwanuka & Tom Misch Money 988 Gloria Jones Tainted Love 987 Toni Braxton He Wasn’t Man Enough 986 John Legend & The Roots Our Generation 985 Sister Sledge All American Girls 984 Jamiroquai Alright 983 Carl Carlton She’s A Bad Mama Jama 982 Sharon Jones & The Dap-Kings Better Things 981 Anita Baker You’re My Everything 980 Jon Batiste I Need You 979 Kool & The Gang Let’s Go Dancing 978 Lizz Wright My Heart 977 Bran van 3000 Astounded 976 Johnnie Taylor What About My Love UUR 3: 14 april 11 uur NON-STOP 975 Des’ree You Gotta Be 974 Craig David Fill Me In 973 Linda Lyndell What A Man 972 Giovanca How Does It Feel 971 Alexander O’ Neal Criticize 970 Marcus King Band Homesick 969 Joss Stone Don’t Cha Wanna Ride 1 968 Candi Staton He Called Me Baby 967 Jamiroquai Seven Days In Sunny June 966 D’Angelo Sugar Daddy 965 Bill Withers In The Name Of Love 964 Michael Kiwanuka One More Night 963 India Arie Can I Walk With You UUR 4: 14 april 12 uur NON-STOP 962 Anthony Hamilton Woo 961 Etta James Tell Mama 960 Erykah Badu Apple Tree 959 Stevie Wonder My Cherie Amour 958 DJ Shadow This Time (I’m Gonna Try It My Way) 957 Alicia Keys A Woman’s Worth 956 Billy Ocean Nights (Feel Like Gettin' Down) 955 Aretha Franklin One Step Ahead 954 Will Smith Men In Black 953 Ray Charles Hallelujah I Love Her So 952 John Legend This Time 951 Blu Cantrell Hit' m Up Style 950 Johnny Pate Shaft In Africa 949 Mary J. -

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black .................................. -

Sun Ra and the Performance of Reckoning

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2015 "The planet is the way it is because of the scheme of words": Sun Ra and the Performance of Reckoning Maryam Ivette Parhizkar Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1086 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] "THE PLANET IS THE WAY IT IS BECAUSE OF THE SCHEME OF WORDS": SUN RA AND THE PERFORMANCE OF RECKONING BY MARYAM IVETTE PARHIZKAR A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York. 2015 i This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Thesis Adviser: ________________________________________ Ammiel Alcalay Date: ________________________________________ Executive Officer: _______________________________________ Matthew K. Gold Date: ________________________________________ THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK ii Abstract "The Planet is the Way it is Because of the Scheme of Words": Sun Ra and the Performance of Reckoning By Maryam Ivette Parhizkar Adviser: Ammiel Alcalay This constellatory essay is a study of the African American sound experimentalist, thinker and self-proclaimed extraterrestrial Sun Ra (1914-1993) through samplings of his wide, interdisciplinary archive: photographs, film excerpts, selected recordings, and various interviews and anecdotes. -

Jazz in Modern American Literature

University of Kansas English Fall 2006 JAZZ IN MODERN AMERICAN LITERATURE INSTRUCTOR: William J. Harris From spirituals to rap, African American music is one of America’s original contributions. In this course we will explore the interaction between jazz, one of the most complex forms of black music, and modern American Literature. Our main question is: How do writers use the forms, ideas and myths of this rich musical tradition? For the authors we are studying, jazz serves as a model and inspiration; they turn to it to find both and American subject matter and an American voice. As well as reading a number of authors, including, Langston Hughes, August Wilson, Jack Kerouac, Ishmael Reed, Michael Ondaatje, Nathaniel Mackey, Jayne Cortez and Toni Morrison, we will listen to a number of African-American musicians and/or composers, including Bessie Smith, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, Sun Ra, Albert Ayler, and Abbey Lincoln. It turns out that we cannot understand the writers well if we do not understand the music well. Moreover, we will view two jazz movies, Amiri Baraka’s Dutchman and Sun Ra’s Space is the Place and will discuss the blues-jazz musical theory of Baraka, Ellison and Albert Murray. REQUIRED READING Moment’s Notice (MN)—Art Lange The Collected Poems (CP)—Langston Hughes Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom—August Wilson Coming Through Slaughter—Michael Ondaatje Jazz—Toni Morrison On the Road—Jack Kerouac Living with Music—Ralph Ellison Invisible Man—Ralph Ellison The LeRoi Jones / Amiri Baraka Reader -

Jayne Cortez

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy Jayne Cortez MAYBE LIBERTY JUSTICE EQUALITY MAYBE IN THE 21ST CENTURY MAYBE ON ANOTHER PLANET MAYBE IN OUTER SPACE MAYBE MAYBE MAYBE NO EQUALITY NO JUSTICE NO LIBERTY “WHAT KIND OF DEMOCRACY IS THIS? Biography Poet, musician, activist, and entrepreneur Jayne Cortez is an accom”- Quick Facts plished woman who uses her work to address social problems in the U.S. and around the world. Over the last 30 years, she has contrib- * Born in 1936 uted greatly to the struggle for racial and gender equality. * African- American poet, Jayne Cortez was born in Fort Huachuca, Arizona and raised in Los singer, and Angeles. After graduating from an arts high school, Cortez enrolled activist in college, but was forced to drop out due to financial problems. * Has recorded From an early age, Cortez was heavily influenced by jazz artists from nine albums the Los Angeles area. In 1954, at the age of 18, Cortez married the with her band, rising jazz star Ornette Coleman. The two had a son, Denardo Cole- the Firespitters man, two years later. In the 1960s Cortez embarked on several endeavors, including participating in the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi, traveling to Europe and Africa, and organizing writing workshops in Watts, This page was researched and submitted by Lucy Corbett and California. Cortez landed in New York City in 1967, where she still Licínia McMorrow on 4/17/03 resides when not teaching or performing around the world. -

African-American Writers

AFRICAN-AMERICAN WRITERS Philip Bader Note on Photos Many of the illustrations and photographs used in this book are old, historical images. The quality of the prints is not always up to current standards, as in some cases the originals are from old or poor-quality negatives or are damaged. The content of the illustrations, however, made their inclusion important despite problems in reproduction. African-American Writers Copyright © 2004 by Philip Bader All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bader, Philip, 1969– African-American writers / Philip Bader. p. cm.—(A to Z of African Americans) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and indexes. ISBN 0-8160-4860-6 (acid-free paper) 1. American literature—African American authors—Bio-bibliography—Dictionaries. 2. African American authors—Biography—Dictionaries. 3. African Americans in literature—Dictionaries. 4. Authors, American—Biography—Dictionaries. I. Title. II. Series. PS153.N5B214 2004 810.9’96073’003—dc21 2003008699 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Joan M. -

Catching Their Attention! Using Nonformal Information Sources to Captivate and Motivate Undergraduates During Library Sessions

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Charleston Library Conference Catching Their Attention! Using Nonformal Information Sources to Captivate and Motivate Undergraduates During Library Sessions Jacqueline Howell Nash University of the West Indies, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/charleston Part of the Information Literacy Commons An indexed, print copy of the Proceedings is also available for purchase at: http://www.thepress.purdue.edu/series/charleston. You may also be interested in the new series, Charleston Insights in Library, Archival, and Information Sciences. Find out more at: http://www.thepress.purdue.edu/series/charleston-insights-library-archival- and-information-sciences. Jacqueline Howell Nash, "Catching Their Attention! Using Nonformal Information Sources to Captivate and Motivate Undergraduates During Library Sessions" (2016). Proceedings of the Charleston Library Conference. http://dx.doi.org/10.5703/1288284316472 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Catching Their Attention! Using Nonformal Information Sources to Captivate and Motivate Undergraduates During Library Sessions Jacqueline Howell Nash, Librarian, University of the West Indies, Main Library—Mona campus, Jamaica Abstract Students at the University of the West Indies in Jamaica are required to complete a course on research and writing for academic purposes. Students are scheduled to visit the library for a hands-on session in the library’s computer laboratory. How can we motivate them to acquire the research skills required in academia? We must first capture their immediate attention and then encourage their academic curiosity. -

Mental Effort from an Lpcomin Disco Sound on This Energetic T, "MY

3, 1979 $2.25 SINGLES SLEEPERS THE WHO, "LONG LIVE ROCK" (prod. not LOUISIANA'S LE ROU listed) (writer: Peter Townshend) by L. S. Me MCA (Towser Tunes, BMI) (3:58).Ini- Pollard) RECORDStially released on their "Odds & Lemed, Sods" Ip, this comes roaring out chapter #00001"Ist "The Kids Are Alright 'sound- rock is vg trackandaptlycapturesthe one isfire theme behind one of rock's leg- blues - rock ends. MCA 41053 tempo shades.. HOT CHOCOLATE, "GOING THROUGH PHILLY CREAM, "MO THE MOTIONS" (prod by M. (prod by Barry- ri Most) (writer: E. Brown) (Finch - Barry -Ingram)(P ry serv.. ley, ASCAP) (3:54). Vocal, string BMI)(3:59).Greatead v re-mixa:] and synthesizer intensity build to trades and brilliant horns to .ontami 4a dramatic climax on this monu- disco sound on thisenergetic ostfamilsir mental effort from an Lpcomin disc. Splendid arrangement/pro- a staid -out and 1p A multi -format smash. Infinity duction give this widespread ap- the rri should 50,016. I. Fantasy/WMOT 862 110 12. THE Cane PATTI SMITH GROUP, "FREDERICK" T, "MY LOVE is" (prod by TH AR V-0. ou p CANDY -11 (prod by T. Rundigren) (writer: P t)(writers: rWright-McCray) was on andful reak Smith)(Ninja,' tASCAFT) (3:01 Iyn.BMI /DErnbet,BMI) (5:48). through t"f, dominan Smith's urgent Vocals, encas it'sfinestefforttodate summer an by ringing guitars, plead the m dikes the most of her grandiose duced by Roy Thomas sage while keyboard lines iz vocaltalentPrecision back-up tinues their esoteric roc of zle. Rundgren produces w chorals, prominent piano Imes & view. -

Representations and Discourses of Black Motherhood in Hip Hop and REPRESENTATIONS and DISCOURSES

Chaney and Brown: Representations and Discourses of Black Motherhood in Hip Hop and REPRESENTATIONS AND DISCOURSES . Representations and Discourses of Black Motherhood in Hip Hop and R&B over Time Cassandra Chaney and Arielle Brown This study will examine how representations and discourses regarding Black motherhood have changed in the Hip Hop and R&B genres over time. Specifically, this scholarly work will contextualize the lyrics of 79 songs (57 Hip Hop songs; 18 R&B songs; 2 songs represented the Hip Hop and R&B genre; 2 songs represented artists who produce music in 5 or 6 genres) from 1961-2015 to identify the ways that Black male and Black female artists described motherhood. Through the use of Black Feminist Theory, and by placing the production of these songs within a sociohistorical context, we provide an in-depth qualitative examination of song lyrics related to Black motherhood. Results gave evidence that representations and discourse of motherhood have been largely shaped by patriarchy as well as cultural, political, and racial politics whose primary aim was to decrease the amount of public support for poor, single Black mothers. In spite of the pathological framing of Black mothers, most notably through the “welfare queen” and “baby mama” stereotypes, a substantial number of Hip Hop and R&B artists have provided a strong counter narrative to Black motherhood by highlighting their positive qualities, acknowledging their individual and collective struggle, and demanding that these women be respected. How has patriarchy influenced the production and release of Hip Hop and R&B songs related to Black motherhood? In what ways has Hip Hop and R&B supported and challenged dominant representations and discourses surrounding Black 1 motherhood? How has Black Feminist Theory validated the experiences of Black mothers in Hip Hop and R&B? This manuscript will respond to these three questions by examining how societal changes have directly influenced how Black mothers in Hip Hop and R&B2 are intellectualized.