Reclaiming the Legends [Long]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ishmael Reed Interviewed

Boxing on Paper: Ishmael Reed Interviewed by Don Starnes [email protected] http://www.donstarnes.com/dp/ Don Starnes is an award winning Director and Director of Photography with thirty years of experience shooting in amazing places with fascinating people. He has photographed a dozen features, innumerable documentaries, commercials, web series, TV shows, music and corporate videos. His work has been featured on National Geographic, Discovery Channel, Comedy Central, HBO, MTV, VH1, Speed Channel, Nerdist, and many theatrical and festival screens. Ishmael Reed [in the white shirt] in New Orleans, Louisiana, September 2016 (photo by Tennessee Reed). 284 Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol.10. no.1, March 2017 Editor’s note: Here author (novelist, essayist, poet, songwriter, editor), social activist, publisher and professor emeritus Ishmael Reed were interviewed by filmmaker Don Starnes during the 2014 University of California at Merced Black Arts Movement conference as part of an ongoing film project documenting powerful leaders of the Black Arts and Black Power Movements. Since 2014, Reed’s interview was expanded to take into account the presidency of Donald Trump. The title of this interview was supplied by this publication. Ishmael Reed (b. 1938) is the winner of the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship (genius award), the renowned L.A. Times Robert Kirsch Lifetime Achievement Award, the Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a Rosenthal Family Foundation Award from the National Institute for Arts and Letters. He has been nominated for a Pulitzer and finalist for two National Book Awards and is Professor Emeritus at the University of California at Berkeley (a thirty-five year presence); he has also taught at Harvard, Yale and Dartmouth. -

Saturn Is Both the Name of Sun Ra's Record Label and the Place That He Claimed As Home, Even Though a More Earthly Account W

Contact: Glenn Siegel, (413) 545-2876 www.fineartscenter.com/magictriangle THE 2004 MAGIC TRIANGLE JAZZ SERIES PRESENTS: Sun Ra Arkestra under the direction of Marshall Allen The Magic Triangle Jazz Series, produced by WMUA, 91.1FM and the Residential Arts Program of the Fine Arts Center at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, continues its 15th season with a performance by Sun Ra Arkestra under the direction of Marshall Allen, featuring Michael Ray, Fred Adams, David Gordon- trumpets; Tyrone Hill, Dave Davis, Dick Griffin-trombones; Marshall Allen, Noël Scott, Ya Ya Abdul Majid, Charles Davis-reeds; Bruce Edwards-electric guitar; John Ore-bass; Luqman Ali, Elson Nascimento, Jimmi Esspirit-percussion on Thursday, March 25, 2004 at Bezanson Recital Hall, University of Massachusetts, Amherst at 8:00 pm. Saturn is both the name of Sun Ra's record label and the place that he claimed as home, even though a more earthly account would have his birthplace (22 May 1914) and resting place (30 May 1993) as Birmingham, Alabama. Composer, arranger, keyboard master and philosophical guru (and Trickster), Le Sony'Ra became an internationally acclaimed exponent of free jazz, a leader in retro-swing and a continuing source of breath-taking originality in the music that we call jazz. Born May 25, 1924 in Louisville, Kentucky, Marshall Allen was stationed in Paris during WW II, and played in Europe with Don Byas and James Moody during the late 40's. Upon his discharge, Mr. Allen enrolled in the Paris Conservatory of Music studying clarinet. Returning to the States in 1951 Marshall settled in Chicago where he met Sun Ra. -

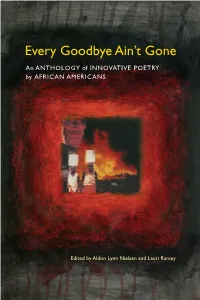

Every Goodbye Ain't Gone

Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone An ANTHOLOGY of INNOVATIVE POETRY by AFRICAN AMERICANS Edited by Aldon Lynn Nielsen and Lauri Ramey Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone You are reading copyrighted material published by the University of Alabama Press. Any posting, copying, or distributing of this work beyond fair use as defined under U.S. Copyright law is illegal and injures the author and publisher. For permission to reuse this work, contact the University of Alabama Press. MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY POETICS Series Editors Charles Bernstein Hank Lazer Series Advisory Board Maria Damon Rachel Blau DuPlessis Alan Golding Susan Howe Nathaniel Mackey Jerome McGann Harryette Mullen Aldon Nielsen Marjorie Perloff Joan Retallack Ron Silliman Lorenzo Thomas Jerr y Ward You are reading copyrighted material published by the University of Alabama Press. Any posting, copying, or distributing of this work beyond fair use as defined under U.S. Copyright law is illegal and injures the author and publisher. For permission to reuse this work, contact the University of Alabama Press. Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone An Anthology of Innovative Poetry by African Americans Edited by ALDON LYNN NIELSEN and LAURI RAMEY THE UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA PRESS Tuscaloosa You are reading copyrighted material published by the University of Alabama Press. Any posting, copying, or distributing of this work beyond fair use as defined under U.S. Copyright law is illegal and injures the author and publisher. For permission to reuse this work, contact the University of Alabama Press. Copyright © 2006 The University of Alabama Press Tuscaloosa, Alabama 35487-0380 All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Typeface: Janson Text ∞ The paper on which this book is printed meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. -

The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry Howard Rambsy II The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor First paperback edition 2013 Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2011 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 5432 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rambsy, Howard. The black arts enterprise and the production of African American poetry / Howard Rambsy, II. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-472-11733-8 (cloth : acid-free paper) 1. American poetry—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Poetry—Publishing—United States—History—20th century. 3. African Americans—Intellectual life—20th century. 4. African Americans in literature. I. Title. PS310.N4R35 2011 811'.509896073—dc22 2010043190 ISBN 978-0-472-03568-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12005-5 (e-book) Cover illustrations: photos of writers (1) Haki Madhubuti and (2) Askia M. Touré, Mari Evans, and Kalamu ya Salaam by Eugene B. Redmond; other images from Shutterstock.com: jazz player by Ian Tragen; African mask by Michael Wesemann; fist by Brad Collett. -

Windward Passenger

MAY 2018—ISSUE 193 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM DAVE BURRELL WINDWARD PASSENGER PHEEROAN NICKI DOM HASAAN akLAFF PARROTT SALVADOR IBN ALI Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East MAY 2018—ISSUE 193 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : PHEEROAN aklaff 6 by anders griffen [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : nicki parrott 7 by jim motavalli General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : dave burrell 8 by john sharpe Advertising: [email protected] Encore : dom salvador by laurel gross Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : HASAAN IBN ALI 10 by eric wendell [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : space time by ken dryden US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIVAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD ReviewS 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, Marilyn Lester, Miscellany 43 Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Event Calendar 44 Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Kevin Canfield, Marco Cangiano, Pierre Crépon George Grella, Laurel Gross, Jim Motavalli, Greg Packham, Eric Wendell Contributing Photographers In jazz parlance, the “rhythm section” is shorthand for piano, bass and drums. -

PROBES #19.2 Devoted to Exploring the Complex Map of Sound Art from Different Points of View Organised in Curatorial Series

Curatorial > PROBES With this section, RWM continues a line of programmes PROBES #19.2 devoted to exploring the complex map of sound art from different points of view organised in curatorial series. Auxiliaries PROBES takes Marshall McLuhan’s conceptual The PROBES Auxiliaries collect materials related to each episode that try to give contrapositions as a starting point to analyse and expose the a broader – and more immediate – impression of the field. They are a scan, not a search for a new sonic language made urgent after the deep listening vehicle; an indication of what further investigation might uncover collapse of tonality in the twentieth century. The series looks and, for that reason, most are edited snapshots of longer pieces. We have tried to at the many probes and experiments that were launched in light the corners as well as the central arena, and to not privilege so-called the last century in search of new musical resources, and a serious over so-called popular genres. In this auxiliary we meet more repurposed new aesthetic; for ways to make music adequate to a world African instruments in several fields, and take one glimpse at the reverse traffic. transformed by disorientating technologies. Interestingly, for the first time, there’s hardly any adoption in contemporary classical circles. Answers on a postcard, please. Curated by Chris Cutler 01. Playlist PDF Contents: 01. Playlist 00:00 Gregorio Paniagua, ‘Anakrousis’, 1978 02. Notes 03. Links 00:06 Randy Weston, interview with Brian Pace (excerpt), 2010 04. Credits Pace is a broadcaster, journalist and mediator of The Pace Report 05. -

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black .................................. -

Sun Ra and the Performance of Reckoning

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2015 "The planet is the way it is because of the scheme of words": Sun Ra and the Performance of Reckoning Maryam Ivette Parhizkar Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1086 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] "THE PLANET IS THE WAY IT IS BECAUSE OF THE SCHEME OF WORDS": SUN RA AND THE PERFORMANCE OF RECKONING BY MARYAM IVETTE PARHIZKAR A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York. 2015 i This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Thesis Adviser: ________________________________________ Ammiel Alcalay Date: ________________________________________ Executive Officer: _______________________________________ Matthew K. Gold Date: ________________________________________ THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK ii Abstract "The Planet is the Way it is Because of the Scheme of Words": Sun Ra and the Performance of Reckoning By Maryam Ivette Parhizkar Adviser: Ammiel Alcalay This constellatory essay is a study of the African American sound experimentalist, thinker and self-proclaimed extraterrestrial Sun Ra (1914-1993) through samplings of his wide, interdisciplinary archive: photographs, film excerpts, selected recordings, and various interviews and anecdotes. -

The Black Power Movement

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and Sharon Harley The Black Power Movement Part 1: Amiri Baraka from Black Arts to Black Radicalism Editorial Adviser Komozi Woodard Project Coordinator Randolph H. Boehm Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Black power movement. Part 1, Amiri Baraka from Black arts to Black radicalism [microform] / editorial adviser, Komozi Woodard; project coordinator, Randolph H. Boehm. p. cm.—(Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide, compiled by Daniel Lewis, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of the Black power movement. ISBN 1-55655-834-1 1. Afro-Americans—Civil rights—History—20th century—Sources. 2. Black power—United States—History—Sources. 3. Black nationalism—United States— History—20th century—Sources. 4. Baraka, Imamu Amiri, 1934– —Archives. I. Woodard, Komozi. II. Boehm, Randolph. III. Lewis, Daniel, 1972– . Guide to the microfilm edition of the Black power movement. IV. Title: Amiri Baraka from black arts to Black radicalism. V. Series. E185.615 323.1'196073'09045—dc21 00-068556 CIP Copyright © 2001 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-834-1. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................ -

Educational Packet and Discussion Guide

Educational Packet & Discussion Guide for Pieces of the Moon by Nick Flint Presented by STAGES in partnership with ONE YEAR LEASE THEATER COMPANY A new stage play adapted to a radio play for live streaming First aired at Stages in Houston TX on July 20, 2020 Originally Commissioned and Developed by One Year Lease Theater Company Directed by Ianthe Demos Sound Design by Brendan Aanes Music Direction by Granville Mullings Studio Engineering and Audio Editing by Tom Beauchel Packet Materials by Isabel Faith Billinghurst 1 oneyearlease.org Who Is Gil Scott-Heron? Today, Gil Scott-Heron is widely considered the “grandfather of rap,” and “the Black Bob Dylan,” though he preferred to call himself a “bluesologist,” which he defined as “a scientist who is concerned with the origin of blues.” Over the course of his life, he published two novels, a collection of poetry, thirteen studio albums, nine live albums, and posthumously published a memoir and an additional album. “It is very important to me that my ideas are understood. It is not as important that I be understood. I believe that this is a matter of respect; your most significant asset is your time and your commitment to invest a portion of it considering my ideas means it is worth a sincere attempt on my part to transmit the essence of the idea. If you are looking, I want to make sure that there is something here for you to find.” A Brief Timeline of Gil’s Life April 1, 1948 - Born in Chicago, Illinois to Bobbie Scott-Heron and Giles “Gil” Heron December 1950 - Moves to Jackson, -

Download .PDF

Yale university press Fall/Winter 2020 Marcus Carey Batchelor Bate Under the Red White A Little History of The Art of Solitude Radical Wordsworth and Blue Poetry Hardcover Hardcover Hardcover Hardcover 978-0-300-25093-0 978-0-300-16964-5 978-0-300-22890-8 978-0-300-23222-6 $23.00 $35.00 $26.00 $25.00 Unwin/Tipling Delbanco Leibovitz Campbell Flights of Passage Why Writing Matters Stan Lee Year of Peril Hardcover Hardcover Hardcover Hardcover 978-0-300-24744-2 978-0-300-24597-4 978-0-300-23034-5 978-0-300-23378-0 $40.00 $26.00 $26.00 $30.00 Van Engen Reynolds Taylor Musonius Rufus City on a Hill Allah Sons of the Waves That One Should Hardcover Hardcover Hardcover Disdain Hardships 978-0-300-22975-2 978-0-300-24658-2 978-0-300-24571-4 Hardcover $30.00 $30.00 $30.00 978-0-300-22603-4 $22.00 RECENT GENERAL INTEREST HIGHLIGHTS Yale university press FALL/WINTER 2020 GENERAL INTEREST 01 JEWISH LIVES® 24 MARGELLOS WORLD REPUBLIC OF LETTERS 26 SCHOLARLY AND ACADEMIC 56 PAPERBACK REPRINTS 73 ART + ARCHITECTURE A 1 front cover illustration: Via Roma, Genoa, Italy, ca. 1895. From Stories for the Years, page 28 “This book is superb, utterly FROM TAKE ARMS AGAINST A SEA OF TROUBLES: convincing, and absolutely invigorating. Bloom’s final argument with mortality What you read and how deeply you read matters almost as much as how you ultimately has a rejuvenating love, work, exercise, vote, practice charity, strive for social justice, cultivate effect upon the reader, kindness and courtesy, worship if you are capable of worship. -

The Avant-Garde in Jazz As Representative of Late 20Th Century American Art Music

THE AVANT-GARDE IN JAZZ AS REPRESENTATIVE OF LATE 20TH CENTURY AMERICAN ART MUSIC By LONGINEU PARSONS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2017 © 2017 Longineu Parsons To all of these great musicians who opened artistic doors for us to walk through, enjoy and spread peace to the planet. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my professors at the University of Florida for their help and encouragement in this endeavor. An extra special thanks to my mentor through this process, Dr. Paul Richards, whose forward-thinking approach to music made this possible. Dr. James P. Sain introduced me to new ways to think about composition; Scott Wilson showed me other ways of understanding jazz pedagogy. I also thank my colleagues at Florida A&M University for their encouragement and support of this endeavor, especially Dr. Kawachi Clemons and Professor Lindsey Sarjeant. I am fortunate to be able to call you friends. I also acknowledge my friends, relatives and business partners who helped convince me that I wasn’t insane for going back to school at my age. Above all, I thank my wife Joanna for her unwavering support throughout this process. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 4 LIST OF EXAMPLES ...................................................................................................... 7 ABSTRACT