64 Doi:10.1162/GREY a 00219 Poster for Aldo Tambellini, Black

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ishmael Reed Interviewed

Boxing on Paper: Ishmael Reed Interviewed by Don Starnes [email protected] http://www.donstarnes.com/dp/ Don Starnes is an award winning Director and Director of Photography with thirty years of experience shooting in amazing places with fascinating people. He has photographed a dozen features, innumerable documentaries, commercials, web series, TV shows, music and corporate videos. His work has been featured on National Geographic, Discovery Channel, Comedy Central, HBO, MTV, VH1, Speed Channel, Nerdist, and many theatrical and festival screens. Ishmael Reed [in the white shirt] in New Orleans, Louisiana, September 2016 (photo by Tennessee Reed). 284 Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol.10. no.1, March 2017 Editor’s note: Here author (novelist, essayist, poet, songwriter, editor), social activist, publisher and professor emeritus Ishmael Reed were interviewed by filmmaker Don Starnes during the 2014 University of California at Merced Black Arts Movement conference as part of an ongoing film project documenting powerful leaders of the Black Arts and Black Power Movements. Since 2014, Reed’s interview was expanded to take into account the presidency of Donald Trump. The title of this interview was supplied by this publication. Ishmael Reed (b. 1938) is the winner of the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship (genius award), the renowned L.A. Times Robert Kirsch Lifetime Achievement Award, the Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a Rosenthal Family Foundation Award from the National Institute for Arts and Letters. He has been nominated for a Pulitzer and finalist for two National Book Awards and is Professor Emeritus at the University of California at Berkeley (a thirty-five year presence); he has also taught at Harvard, Yale and Dartmouth. -

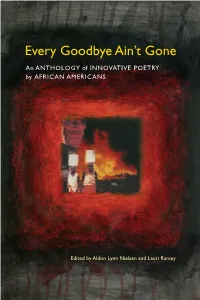

Every Goodbye Ain't Gone

Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone An ANTHOLOGY of INNOVATIVE POETRY by AFRICAN AMERICANS Edited by Aldon Lynn Nielsen and Lauri Ramey Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone You are reading copyrighted material published by the University of Alabama Press. Any posting, copying, or distributing of this work beyond fair use as defined under U.S. Copyright law is illegal and injures the author and publisher. For permission to reuse this work, contact the University of Alabama Press. MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY POETICS Series Editors Charles Bernstein Hank Lazer Series Advisory Board Maria Damon Rachel Blau DuPlessis Alan Golding Susan Howe Nathaniel Mackey Jerome McGann Harryette Mullen Aldon Nielsen Marjorie Perloff Joan Retallack Ron Silliman Lorenzo Thomas Jerr y Ward You are reading copyrighted material published by the University of Alabama Press. Any posting, copying, or distributing of this work beyond fair use as defined under U.S. Copyright law is illegal and injures the author and publisher. For permission to reuse this work, contact the University of Alabama Press. Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone An Anthology of Innovative Poetry by African Americans Edited by ALDON LYNN NIELSEN and LAURI RAMEY THE UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA PRESS Tuscaloosa You are reading copyrighted material published by the University of Alabama Press. Any posting, copying, or distributing of this work beyond fair use as defined under U.S. Copyright law is illegal and injures the author and publisher. For permission to reuse this work, contact the University of Alabama Press. Copyright © 2006 The University of Alabama Press Tuscaloosa, Alabama 35487-0380 All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Typeface: Janson Text ∞ The paper on which this book is printed meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. -

The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry Howard Rambsy II The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor First paperback edition 2013 Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2011 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 5432 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rambsy, Howard. The black arts enterprise and the production of African American poetry / Howard Rambsy, II. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-472-11733-8 (cloth : acid-free paper) 1. American poetry—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Poetry—Publishing—United States—History—20th century. 3. African Americans—Intellectual life—20th century. 4. African Americans in literature. I. Title. PS310.N4R35 2011 811'.509896073—dc22 2010043190 ISBN 978-0-472-03568-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12005-5 (e-book) Cover illustrations: photos of writers (1) Haki Madhubuti and (2) Askia M. Touré, Mari Evans, and Kalamu ya Salaam by Eugene B. Redmond; other images from Shutterstock.com: jazz player by Ian Tragen; African mask by Michael Wesemann; fist by Brad Collett. -

Unobtainium-Vol-1.Pdf

Unobtainium [noun] - that which cannot be obtained through the usual channels of commerce Boo-Hooray is proud to present Unobtainium, Vol. 1. For over a decade, we have been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We invite you to our space in Manhattan’s Chinatown, where we encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections by appointment or chance. Please direct all inquiries to Daylon ([email protected]). Terms: Usual. Not onerous. All items subject to prior sale. Payment may be made via check, credit card, wire transfer or PayPal. Institutions may be billed accordingly. Shipping is additional and will be billed at cost. Returns will be accepted for any reason within a week of receipt. Please provide advance notice of the return. Please contact us for complete inventories for any and all collections. The Flash, 5 Issues Charles Gatewood, ed. New York and Woodstock: The Flash, 1976-1979. Sizes vary slightly, all at or under 11 ¼ x 16 in. folio. Unpaginated. Each issue in very good condition, minor edgewear. Issues include Vol. 1 no. 1 [not numbered], Vol. 1 no. 4 [not numbered], Vol. 1 Issue 5, Vol. 2 no. 1. and Vol. 2 no. 2. Five issues of underground photographer and artist Charles Gatewood’s irregularly published photography paper. Issues feature work by the Lower East Side counterculture crowd Gatewood associated with, including George W. Gardner, Elaine Mayes, Ramon Muxter, Marcia Resnick, Toby Old, tattooist Spider Webb, author Marco Vassi, and more. -

One of a Kind, Unique Artist's Books Heide

ONE OF A KIND ONE OF A KIND Unique Artist’s Books curated by Heide Hatry Pierre Menard Gallery Cambridge, MA 2011 ConTenTS © 2011, Pierre Menard Gallery Foreword 10 Arrow Street, Cambridge, MA 02138 by John Wronoski 6 Paul* M. Kaestner 74 617 868 20033 / www.pierremenardgallery.com Kahn & Selesnick 78 Editing: Heide Hatry Curator’s Statement Ulrich Klieber 66 Design: Heide Hatry, Joanna Seitz by Heide Hatry 7 Bill Knott 82 All images © the artist Bodo Korsig 84 Foreword © 2011 John Wronoski The Artist’s Book: Rich Kostelanetz 88 Curator’s Statement © 2011 Heide Hatry A Matter of Self-Reflection Christina Kruse 90 The Artist’s Book: A Matter of Self-Reflection © 2011 Thyrza Nichols Goodeve by Thyrza Nichols Goodeve 8 Andrea Lange 92 All rights reserved Nick Lawrence 94 No part of this catalogue Jean-Jacques Lebel 96 may be reproduced in any form Roberta Allen 18 Gregg LeFevre 98 by electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or information storage retrieval Tatjana Bergelt 20 Annette Lemieux 100 without permission in writing from the publisher Elena Berriolo 24 Stephen Lipman 102 Star Black 26 Larry Miller 104 Christine Bofinger 28 Kate Millett 108 Curator’s Acknowledgements Dianne Bowen 30 Roberta Paul 110 My deepest gratitude belongs to Pierre Menard Gallery, the most generous gallery I’ve ever worked with Ian Boyden 32 Jim Peters 112 Dove Bradshaw 36 Raquel Rabinovich 116 I want to acknowledge the writers who have contributed text for the artist’s books Eli Brown 38 Aviva Rahmani 118 Jorge Accame, Walter Abish, Samuel Beckett, Paul Celan, Max Frisch, Sam Hamill, Friedrich Hoelderin, John Keats, Robert Kelly Inge Bruggeman 40 Osmo Rauhala 120 Andreas Koziol, Stéphane Mallarmé, Herbert Niemann, Johann P. -

The Box As Meeting Place Artistic Encounters in Aspen Magazine (1965-1971)

The Box as Meeting Place Artistic Encounters in Aspen Magazine (1965-1971) 129 Maarten van Gageldonk Aspen was a multimedia magazine, each issue presented as a box full of surpri- ses by artists, writers, thinkers, and unknowns. What kept contributors as diverse as John Lennon, Yoko Ono, J.G. Ballard, and David Hockney together? In 1965 New York magazine editor Phyllis dia revolution. Aspen would return the func- Johnson travelled to Aspen, Colorado, to tion of the magazine to ‘the original meaning partake in the International Design Confe- of the word, as “a storehouse, a cache, a ship rence Aspen (IDCA) and returned home asking laden with stores”’, and in doing so it would herself how the traditional magazine could be liberate it from its linearity and two-dimen- adapted for the modern age. Later that year sionality, as well as from the dominance of she launched her answer: Aspen Magazine, printed matter.1 Accordingly, throughout the the multimedia magazine in a box. Between years Aspen’s slim boxes and folders contained 1965 and 1971 ten issues of Aspen appeared, posters, flip books, newspapers, stamps, a each put together by a different guest editor kite, a miniature sculpture, flexi discs with and devoted to a different theme, ranging music and audio recordings, and in 1967 even from Pop Art and Minimalism to psychedelic a reel of Super 8 film – a first for any magazine. art and Asian culture. Opening one of Aspen’s To its subscribers the contents of each issue boxes now is like unearthing a time capsule came as a surprise and connecting the various and its contributor list reads like a sample items demanded a non-trivial amount of activ- sheet of the 1960s, including work by William ity on the account of the ‘reader’. -

Aldo Tambellini

Aldo Tambellini 11 March - 6 August 2017 A Portrait of Aldo Tambellini, 2010 • Photo: Gerard Malanga Introduction As a key figure in the 1960s underground scene of New York – a missing link between the European avant-garde and the artistic move- ments that followed Abstract Expressionism – Aldo Tambellini (born 1930 in Syracuse, NY, US) is an experimenter, agitator, and a major catalyst of in- novation in the field of multimedia art. Tambellini took the transformational potential of artistic expression that stems from painting and sculpture and brought it to the experiences of Expanded Cinema. After his early experiments with color in the 1950s, the artist em- braced BLACK as an artistic, philosophical, social, and political commit- ment, and started to use mainly this color in his works. The American Civ- il Rights Movement and the struggle for racial equality, the Vietnam War, and the space-age were influences on his visionary oeuvre, unique in that it demonstrates the fragile balance between an artist’s absorption of the stimuli provided by contemporary new technologies and the social and po- litical environment of his time. Attracted above all by the energetic nature of painting, Tambellini transferred a meticulous expression of the language and power of gesture – first onto slides, and later onto film frames and vid- eo. Over the course of the 1960s he created his Black Project from which emerged: the Black Film Series, 16 mm films focused on philosophical and social facets of black; the Black Performances, multimedia performances he called “Electromedia” which are based on his theories of the integration of the arts; the Black Video Series and Black TV, which took his mode of ex- perimentation further into video and television technologies. -

ELCOCK-DISSERTATION.Pdf

HIGH NEW YORK THE BIRTH OF A PSYCHEDELIC SUBCULTURE IN THE AMERICAN CITY A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By CHRIS ELCOCK Copyright Chris Elcock, October, 2015. All rights reserved Permission to Use In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of History Room 522, Arts Building 9 Campus Drive University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 Canada i ABSTRACT The consumption of LSD and similar psychedelic drugs in New York City led to a great deal of cultural innovations that formed a unique psychedelic subculture from the early 1960s onwards. -

A Dramatic Exploration of Women and Their Agency in the Black Panther Party

Kennesaw State University DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University Master of Arts in American Studies Capstones Interdisciplinary Studies Department Spring 5-2017 Revolutionary Every Day: A Dramatic Exploration of Women and Their Agency in The lB ack Panther Party. Kristen Michelle Walker Kennesaw State University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/mast_etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Studies Commons, Playwriting Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Walker, Kristen Michelle, "Revolutionary Every Day: A Dramatic Exploration of Women and Their Agency in The lB ack Panther Party." (2017). Master of Arts in American Studies Capstones. 12. http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/mast_etd/12 This Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Interdisciplinary Studies Department at DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Arts in American Studies Capstones by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVOLUTIONARY EVERY DAY: A DRAMATIC EXPLORATION OF WOMEN AND THEIR AGENCY IN THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY A Creative Writing Capstone Presented to The Academic Faculty by Kristen Michelle Walker In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in American Studies Kennesaw State University May 2017 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………...…………………………………………...……. -

The Man Who Turned on the World

The Man Who Turned on the World Michael Hollingshead FOREWORD by Alan Bold 'THE MIRACULOUS MAN' (For Michael Hollingshead) Date of birth unknown, and inconsistent In the presentation of his point of view, He may have got near Kapilavastu After some service in the orient. Certainly he settled for a while For something eerie happened at Bodh Gaya Where ho overcame an enemy named Mara And retained a smug, but somehow moving, smile. Later this became more pure and poignant Until some vile and murderous abuse Mocked his claim to be king of the jews And made him shrewd and militant. From Medina he took Mecca by force Saying man was made from wicked gouts of blood. It's different to assess just how much good He ever did. Or ever will, of course Edinburgh 1972 1. A Lovin' Spoonful In the beginning, more exactly... in 1943, Albert Hofmann, a Swiss bio-chemist working at the Sandoz Pharmaceutical Laboratories in Basel, discovered—by accident, of course; one does not deliberately create such a situation—a new drug which had some very remarkable effects on the human consciousness. The name of this drug was d-Lysergic Acid Diethylamide Tartrate-25, a semi-synthetic compound, the Iysergic acid portion of which is a natural product of the ergot fungus Claviceps purpurea, which grows on rye and other grains. Its most striking pharmacological characteristic is its extreme potency—it is effective at doses of as little as ten-millionths of a gram, which makes it 5000 times more potent than mescaline. It was during the synthesis of d-LSD-25 that chance intervened when Dr. -

Radicalism, Racism, and Affirmative Action: in Defense of a Historical Approach

Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center Scholarly Works Faculty Scholarship 1999 Radicalism, Racism, and Affirmative Action: In Defense of a Historical Approach Deseriee Kennedy Touro Law Center Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/scholarlyworks Part of the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation 27 Cap. U. L. Rev. 61 (1999) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RADICALISM, RACISM AND AFFIRMATIVE ACTION: IN DEFENSE OF A HISTORICAL APPROACH DESERIEE KENNEDY* "The history of the world is the history, not of individuals, but of groups, not of nations, but of races, and he who ignores or seeks to override the race idea in human history ignores and overrides the central thought of all history."l "No history, no justice; no justice, no peace. What it means to live in 2 history is to recognize that the past has not passed." Radicalism, in general and as resistance to injustice and power imbalances, has played a noble part in history. In an editorial in support of affirmative action, 3 a local columnist recently commented that he was struck by the irony and ahistoricism of the current virulent resistance to radicalism and embrace of conservatism. He noted that American history has been marked by radical resistance: George Washington was radical in his opposition to the British crown; Abraham Lincoln was radical in his resistance to Southern whites; Dr. -

Cultural Frames in the Gay Liberation Movement

The Hilltop Review Volume 7 Issue 2 Spring Article 17 April 2015 From “Black is Beautiful” to “Gay Power”: Cultural Frames in the Gay Liberation Movement Eric Denby Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/hilltopreview Part of the Cultural History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Denby, Eric (2015) "From “Black is Beautiful” to “Gay Power”: Cultural Frames in the Gay Liberation Movement," The Hilltop Review: Vol. 7 : Iss. 2 , Article 17. Available at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/hilltopreview/vol7/iss2/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Hilltop Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact wmu- [email protected]. 132 From “Black is Beautiful” to “Gay Power”: Cultural Frames in the Gay Liberation Movement Runner-Up, 2014 Graduate Humanities Conference By Eric Denby Department of History [email protected] The 1960s and 1970s were a decade of turbulence, militancy, and unrest in America. The post-World War II boom in consumerism and consumption made way for a new post- materialist societal ethos, one that looked past the American dream of home ownership and material wealth. Many citizens were now concerned with social and economic equality, justice for all people of the world, and a restructuring of the capitalist system itself. According to Max Elbaum, the