The Box As Meeting Place Artistic Encounters in Aspen Magazine (1965-1971)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unobtainium-Vol-1.Pdf

Unobtainium [noun] - that which cannot be obtained through the usual channels of commerce Boo-Hooray is proud to present Unobtainium, Vol. 1. For over a decade, we have been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We invite you to our space in Manhattan’s Chinatown, where we encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections by appointment or chance. Please direct all inquiries to Daylon ([email protected]). Terms: Usual. Not onerous. All items subject to prior sale. Payment may be made via check, credit card, wire transfer or PayPal. Institutions may be billed accordingly. Shipping is additional and will be billed at cost. Returns will be accepted for any reason within a week of receipt. Please provide advance notice of the return. Please contact us for complete inventories for any and all collections. The Flash, 5 Issues Charles Gatewood, ed. New York and Woodstock: The Flash, 1976-1979. Sizes vary slightly, all at or under 11 ¼ x 16 in. folio. Unpaginated. Each issue in very good condition, minor edgewear. Issues include Vol. 1 no. 1 [not numbered], Vol. 1 no. 4 [not numbered], Vol. 1 Issue 5, Vol. 2 no. 1. and Vol. 2 no. 2. Five issues of underground photographer and artist Charles Gatewood’s irregularly published photography paper. Issues feature work by the Lower East Side counterculture crowd Gatewood associated with, including George W. Gardner, Elaine Mayes, Ramon Muxter, Marcia Resnick, Toby Old, tattooist Spider Webb, author Marco Vassi, and more. -

ELCOCK-DISSERTATION.Pdf

HIGH NEW YORK THE BIRTH OF A PSYCHEDELIC SUBCULTURE IN THE AMERICAN CITY A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By CHRIS ELCOCK Copyright Chris Elcock, October, 2015. All rights reserved Permission to Use In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of History Room 522, Arts Building 9 Campus Drive University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 Canada i ABSTRACT The consumption of LSD and similar psychedelic drugs in New York City led to a great deal of cultural innovations that formed a unique psychedelic subculture from the early 1960s onwards. -

Nyuprogram.Pdf

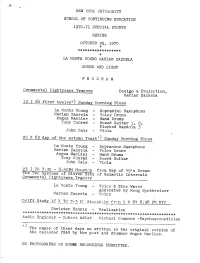

NEW YORK UNIVERSiTY SCHOOL OF CONTINUING EDUCATION 1970-71 SPECIAL EVENTS SERIES OCTOBER 25, 1970 LA MONTE YOUNG MARIAN ZAZEELA SOUND AND LIGHT P R 0 G R A M Ornamental Lightyears Tracery Design & Projection, Marian Zaz--ela 12 1 64 first twelve+) Sunday Morning Blues La Monte Young - Sopranino Saxophone Marian Zaze--la - Voice Drone Angus MacLise - Hand Drums Tony Conrad. - Bowed Guitar 1, 2, Plucked Mandola 3 John Cale - Viola 20 X 63 day of the autumn feast-0 Sunday Morning Blues La Monte Young Sppranino Saxophone Marian Zaz--ela Voice Drone AngusC=) MacLise Hand Drums Tony Conrad. Bowed Guitax John Cale Viola 23 1 70 7 :35 - 8 :40PM Houston from Map of 49's Dream Th-eTwo Systems of 01-evenSat s of Galactic Intervals Ornamental Lightyears Tracery La, Monte Young - Voice & Sine Waves generated by Moog Synthesizer Maxian Zazeela - Voicea Drift Study 16 X 70 Pt' StockEolm frrm 5 V 67 6 :38 PM NYC Christer Hennix Realization Audio Engineer - Rob-~=rt Adler Michael Commons -Psychoacoustician The names of these days as written in the the original version of calendar YEAR by the pcet and. drummer Angus MacLise . NO PHOTOGRAPHS OR SOUND RECORDINGS PERMITTED . P R 0 G R A M N 0 T E S Ornamental Lightyears Tracery The Projections form part of a series of light works designed for live Performance on three or more slide projectors . The series contains numerous black and white negative and positive photographs of modular sections of several closely related designs . Each slide mount holds a photograph and a combination of colored gals . -

Your Pretty Face Is Going to Hell the Dangerous Glitter of David Bowie, Iggy Pop,And Lou Reed

PF00fr(i-viii;vibl) 9/3/09 4:01 PM Page iii YOUR PRETTY FACE IS GOING TO HELL THE DANGEROUS GLITTER OF DAVID BOWIE, IGGY POP,AND LOU REED Dave Thompson An Imprint of Hal Leonard Corporation New York PF00fr(i-viii;vibl) 9/16/09 3:34 PM Page iv Frontispiece: David Bowie, Iggy Pop, and Lou Reed (with MainMan boss Tony Defries laughing in the background) at the Dorchester Hotel, 1972. Copyright © 2009 by Dave Thompson All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, with- out written permission, except by a newspaper or magazine reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review. Published in 2009 by Backbeat Books An Imprint of Hal Leonard Corporation 7777 West Bluemound Road Milwaukee, WI 53213 Trade Book Division Editorial Offices 19 West 21st Street, New York, NY 10010 Printed in the United States of America Book design by David Ursone Typography by UB Communications Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Thompson, Dave, 1960 Jan. 3- Your pretty face is going to hell : the dangerous glitter of David Bowie, Iggy Pop, and Lou Reed / Dave Thompson. — 1st paperback ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and discography. ISBN 978-0-87930-985-5 (alk. paper) 1. Bowie, David. 2. Pop, Iggy, 1947-3. Reed, Lou. 4. Rock musicians— England—Biography. 5. Punk rock musicians—United States—Biography. I. Title. ML400.T47 2009 782.42166092'2—dc22 2009036966 www.backbeatbooks.com PF00fr(i-viii;vibl) 9/3/09 4:01 PM Page vi PF00fr(i-viii;vibl) 9/3/09 4:01 PM Page vii CONTENTS Prologue . -

The Man Who Turned on the World

The Man Who Turned on the World Michael Hollingshead FOREWORD by Alan Bold 'THE MIRACULOUS MAN' (For Michael Hollingshead) Date of birth unknown, and inconsistent In the presentation of his point of view, He may have got near Kapilavastu After some service in the orient. Certainly he settled for a while For something eerie happened at Bodh Gaya Where ho overcame an enemy named Mara And retained a smug, but somehow moving, smile. Later this became more pure and poignant Until some vile and murderous abuse Mocked his claim to be king of the jews And made him shrewd and militant. From Medina he took Mecca by force Saying man was made from wicked gouts of blood. It's different to assess just how much good He ever did. Or ever will, of course Edinburgh 1972 1. A Lovin' Spoonful In the beginning, more exactly... in 1943, Albert Hofmann, a Swiss bio-chemist working at the Sandoz Pharmaceutical Laboratories in Basel, discovered—by accident, of course; one does not deliberately create such a situation—a new drug which had some very remarkable effects on the human consciousness. The name of this drug was d-Lysergic Acid Diethylamide Tartrate-25, a semi-synthetic compound, the Iysergic acid portion of which is a natural product of the ergot fungus Claviceps purpurea, which grows on rye and other grains. Its most striking pharmacological characteristic is its extreme potency—it is effective at doses of as little as ten-millionths of a gram, which makes it 5000 times more potent than mescaline. It was during the synthesis of d-LSD-25 that chance intervened when Dr. -

64 Doi:10.1162/GREY a 00219 Poster for Aldo Tambellini, Black

Poster for Aldo Tambellini, Black Zero (1965–68), 1965. 64 doi:10.1162/GREY_a_00219 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00219 by guest on 01 October 2021 The Subject of Black: Abstraction and the Politics of Race in the Expanded Cinema Environment NADJA MILLNER-LARSEN Midway through a 2012 reperformance of the expanded cinema event Black Zero (1965–1968)—a collage of jazz improvisation, light projection, poetry reading, dance performance, and televisual noise—the phrases of Calvin C. Hernton’s poem “Jitterbugging in the Streets” reached a crescendo: 1 TERROR is in Harlem A FEAR so constant Black men crawl the pavement as if they were snakes, and snakes turn to sticks that beat the heads of those who try to stand up— A Genocide so blatant Every third child will do the junky-nod in the whore-scented night before semen leaps from his loins— And Fourth of July comes with the blasting bullet in the belly of a teenager Against which no Holyman, no Christian housewife In Edsel automobile Will cry out this year Jitterbugging in the streets. 2 Hernton’s rendering of the 1964 Harlem uprising, originally published as part of the New Jazz Poets record, is gradually engulfed by a bombastic soundscape dominated by an archival recording of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) Apollo 8 launch interspersed with video static and the familiar drone of a vacuum cleaner. Surrounded by black walls spattered with Grey Room 67, Spring 2017, pp. 64–99. © 2017 Grey Room, Inc. and Massachusetts Institute of Technology 65 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00219 by guest on 01 October 2021 slides of slow-rotating abstract spheres whose contours melt into gaseous implo - sions, viewers are stimulated by flashing television monitors, black-and-white projections from hand-painted celluloid, and video images of black children pro - jected onto a glacially expanding black balloon. -

The Velvet Underground By: Kao-Ying Chen Shengsheng Xu Makenna Borg Sundeep Dhanju Sarah Lindholm Group Introduction

The Velvet Underground By: Kao-Ying Chen Shengsheng Xu Makenna Borg Sundeep Dhanju Sarah Lindholm Group Introduction The Velvet Underground helped create one of the first proto-punk songs and paved the path for future songs alike. Our group chose this group because it is one of those groups many people do not pay attention to very often and they are very unique and should be one that people should learn about. Shengsheng Biography The Velvet Underground was an American rock band formed in New York City in 1964. They are also known as The Warlocks and The Falling Spikes. Best-known members: Lou Reed and John Cale. 1967 debut album, “The Velvet Underground & Nico” was named the 13th Greatest Album of All Time, and the “most prophetic rock album ever http://t2.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcTpZBIJzRM1H- made” by Rolling Stone in 2003. GhQN6gcpQ10MWXGlqkK03oo543ZbNUefuLNAvVRA Ranked #19 on the “100 Greatest Artists of All Time” by Rolling Stone. Shengsheng Biography From 1964-1965: Lou Reed (worked as a songwriter) met John Cale (Welshman who came to United States to study classical music) and they formed, The Primitives. Reed and Cale recruited Sterling Morrison to play the guitar (college classmate of Reed’s) as a replacement for Walter De Maria. Angus MacLise joined as a percussionist to form a group of four. And this quartet was first named The Warlocks, then The Falling Spikes. Introduced by Michael Leigh, the name “The Velvet Underground” was finally adopted by the group in Nov 1965. Shengsheng Biography From 1965-1966: Andy Warhol became the group’s manager. -

Untitled) 1961, That Spewed Shaving Cream, Grand Central Moderns Gallery, NYC

Critical Mass Happenings Fluxus Performance Intermedia and Rutgers University 1958-1972 By: Geoffrey Hendricks ISBN: 0813533031 See detail of this book on Amazon.com Book served by AMAZON NOIR (www.amazon-noir.com) project by: PAOLO CIRIO paolocirio.net UBERMORGEN.COM ubermorgen.com ALESSANDRO LUDOVICO neural.it Page 1 Critical Mass: Some Reflections M O R D E C A I - M A R K M A C L O W Icons of my childhood were the piles of red-bound copies of An Anthology that my father, Jackson Mac Low, received for having edited and published it. Despite his repeated declarations that he was not a part of George Maciunas's self-declared movement, my father's involve- ment in the first Fluxus book left him irrevocably tangled in it. I myself seem to have been influenced by my father's experimental, algorithmic approach to poetry, and ended up a computational astrophysicist, studying how stars form out of the chaotic, turbulent interstellar gas. I think there was some hope that with this background I might explain the true, or correct, meaning of the term "critical mass." Unfortunately, as a scientist, I have no special access to truth, and correctness depends entirely on con- text. Let me explain this a bit before discussing the term "critical mass" itself. Science is often taught as if it consisted of a series of true facts, strung together with a narrative of how these facts were discovered. The actual practice of sci- ence, however, requires the assumption that nothing is guaranteed to be true except as, and only so far as, it can be confirmed by empirical evidence. -

Literary Miscellany

Literary Miscellany Chiefly Recent Acquisitions. Catalogue 316 WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 TEMPLE STREET NEW HAVEN, CT. 06511 USA 203.789.8081 FAX: 203.865.7653 [email protected] www.williamreesecompany.com TERMS Material herein is offered subject to prior sale. All items are as described, but are considered to be sent subject to approval unless otherwise noted. Notice of return must be given within ten days unless specific arrangements are made prior to shipment. All returns must be made conscientiously and expediently. Connecticut residents must be billed state sales tax. Postage and insurance are billed to all non-prepaid domestic orders. Orders shipped outside of the United States are sent by air or courier, unless otherwise requested, with full charges billed at our discretion. The usual courtesy discount is extended only to recognized booksellers who offer reciprocal opportunities from their catalogues or stock. We have 24 hour telephone answering, and a Fax machine for receipt of orders or messages. Catalogue orders should be e-mailed to: [email protected] We do not maintain an open bookshop, and a considerable portion of our literature inventory is situated in our adjunct office and warehouse in Hamden, CT. Hence, a minimum of 24 hours notice is necessary prior to some items in this catalogue being made available for shipping or inspection (by appointment) in our main offices on Temple Street. We accept payment via Mastercard or Visa, and require the account number, expiration date, CVC code, full billing name, address and telephone number in order to process payment. Institutional billing requirements may, as always, be accommodated upon request. -

The Power of the Center : a Study of Composition in the Visual Arts, 20Th Anniversary Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE POWER OF THE CENTER : A STUDY OF COMPOSITION IN THE VISUAL ARTS, 20TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Rudolf Arnheim | 250 pages | 23 Oct 2009 | University of California Press | 9780520261266 | English | Berkerley, United States The Power of the Center : A Study of Composition in the Visual Arts, 20th Anniversary Edition PDF Book Finally the objects in the still-life have come into view: a compotier or fruit dish , a glass, apples, and a knife, arranged on a cloth and set before patterned wallpaper. The Egyptian sculptor, cutting into a block of stone, has shaped and organized the parts of his work so that they produce a particular sense of order, a unique and expressive total form. Lawrence Alloway Lawrence Alloway — was a key figure in the development of modern art in Europe and America, maintaining a prolific output as an art critic and curator. With new knowledge about the pigments and techniques used in the painting, art historians, scientists, and conservators from the Getty Research Institute, the Getty Conservation Institute, and the Getty Museum, along with a distinguished group of invited scholars, consider how these findings modify an understanding of Pollock's process and larger body of work. Young has long claimed to have written the ''underlying music composition'' -- essentially a series of pre-set intervals to be used within a lengthy drone -- for ''The Tortoise, His Dreams and Journeys,'' the piece the Theater of Eternal Music dedicated itself to performing during this period. Related Articles. Among the dynamic constituents of visual hubs he includes spirals, intersections, crossings and bridging devices, bipolarities, estrangements and separations. -

1965 Falling Spikes: a Fake Tape

Source/Title: FallingSpikes 1965 The text says: FALLING SPIKES LOU REED, JOHN CALE, STERLING MORRISON, ANGUS MACLISE IN 1965 A NEW YORK BAND CALLED THE PRIMITIVES CHANGED IT'S NAME TO THE WARLOCKS AND THEN TO THE FALLING SPIKES, LATER TO BECOME FAMOUS AS THE VELVET UNDERGROUND. THIS RARE RECORDING FROM 1965 IS THEIR ONLY RECORDED WORK. Actually: it's a tape copy of the "Live at the Boston Tea Party" LP (catalogue Velvet 1, UK, 1985) but the album Side One is the tape B-Side (and Side Two becomes the A-Side). Tracklist (not given on sleeve insert): A-Side B-Side Heroin What Goes On (the rest) Move Right In I Can't Stand It I'm Set Free Candy Says Run Run Run Beginning to See the Light Waiting for the Man White Light/White Heat What Goes On (part) Pale Blue Eyes After Hours Equivalent: Tape 3, VU LIVE - BOSTON TEA PARTY (JAN. 10, 1969) (but it's a loose equivalent). Sound: Bad to Average. Side B is too fast, like the album, with clicks and tape whirrs on "Candy Says" and is basically unlistenable. Side A is average at best. Notes: What a gem this would have been, but it's either a bad joke or a deliberate fraud. The sleeve insert is badly copied and hand-cut with blunt scissors, the text says "IT'S" when it should be "ITS", there is no Cale or Maclise and sloppy copying splits WGO over two sides needlessly with the first part lasting just a few seconds. -

Lou Reed: the Life Pdf, Epub, Ebook

LOU REED: THE LIFE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mick Wall | 256 pages | 15 Nov 2015 | Orion Publishing Co | 9781409153047 | English | London, United Kingdom Lou Reed: The Life PDF Book The book ends, as biographies are wont to do, with the death of its subject. Entertainment Weekly. This is far from a rock hagiography. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. There's also a fairly comprehensive discography at the back, though strangely especially since a sizeable part of the book deals with the Velvets records it starts with a compilation. While I was certainly impatient, as per usual with music bios, to be finished with Lou Reed , DeCurtis, an editor and long-time contributor at Rolling Stone , is a more fluent and perceptive critic than many biographers and his observations provided a way in, for me, to some of Reed's more challenging work reading about music is so much more satisfying in the YouTube Age - I used to read about a record and then, sometimes, have to wait months or even years before actually hearing it. Retrieved October 25, He also talks about the gig we both witnessed at the Hammersmith Apollo in 79? Retrieved December 12, It was rediscovered in the s and allowed Reed to drop "Walk on the Wild Side" from his concerts. He credited Schwartz with showing him how "with the simplest language imaginable, and very short, you can accomplish the most astonishing heights. May 16, Lindsay rated it it was amazing Shelves: music. Hardcover , pages. Colossal Books. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Jazz Latin New Age.