The Prehension of Painting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unobtainium-Vol-1.Pdf

Unobtainium [noun] - that which cannot be obtained through the usual channels of commerce Boo-Hooray is proud to present Unobtainium, Vol. 1. For over a decade, we have been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We invite you to our space in Manhattan’s Chinatown, where we encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections by appointment or chance. Please direct all inquiries to Daylon ([email protected]). Terms: Usual. Not onerous. All items subject to prior sale. Payment may be made via check, credit card, wire transfer or PayPal. Institutions may be billed accordingly. Shipping is additional and will be billed at cost. Returns will be accepted for any reason within a week of receipt. Please provide advance notice of the return. Please contact us for complete inventories for any and all collections. The Flash, 5 Issues Charles Gatewood, ed. New York and Woodstock: The Flash, 1976-1979. Sizes vary slightly, all at or under 11 ¼ x 16 in. folio. Unpaginated. Each issue in very good condition, minor edgewear. Issues include Vol. 1 no. 1 [not numbered], Vol. 1 no. 4 [not numbered], Vol. 1 Issue 5, Vol. 2 no. 1. and Vol. 2 no. 2. Five issues of underground photographer and artist Charles Gatewood’s irregularly published photography paper. Issues feature work by the Lower East Side counterculture crowd Gatewood associated with, including George W. Gardner, Elaine Mayes, Ramon Muxter, Marcia Resnick, Toby Old, tattooist Spider Webb, author Marco Vassi, and more. -

Henry Flynt and Generative Aesthetics Redefined

1. In one of a series of video interviews conducted by Benjamin Piekut in 2005, Henry Flynt mentions his involvement in certain sci-fi literary scenes of the 1970s.1 Given his background in mathematics and analytic philosophy, in addition to his radical Marxist agitation as a member of 01/12 the Workers World Party in the sixties, Flynt took an interest in the more speculative aspects of sci-fi. “I was really thinking myself out of Marxism,” he says. “Trying to strip away its assumptions – [Marx’s] assumption that a utopia was possible with human beings as raw material.” Such musings would bring Flynt close to sci-fi as he considered the revision of the J.-P. Caron human and what he called “extraterrestrial politics.” He mentions a few pamphlets that he d wrote and took with him to meetings with sci-fi e On Constitutive n i writers, only to discover, shockingly, that they f e d had no interest in such topics. Instead, e R Dissociations conversations drifted quickly to the current state s c i 2 t of the book market for sci-fi writing. e h t ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊI’m interested in this anecdote in the as a Means of s e contemporary context given that sci-fi writing A e v has acquired status as quasi-philosophy, as a i t World- a r medium where different worlds are fashioned, e n sometimes guided by current scientific research, e G as in so-called “hard” sci-fi. While I don’t intend Unmaking: d n a here to examine sci-fi directly, it does allude to t n y the nature of worldmaking and generative l Henry Flynt and F aesthetics – the nature of which I hope to y r n illuminate below by engaging with Flynt’s work, e H Generative : as well as that of the philosophers Nelson g n i Goodman and Peter Strawson. -

One of a Kind, Unique Artist's Books Heide

ONE OF A KIND ONE OF A KIND Unique Artist’s Books curated by Heide Hatry Pierre Menard Gallery Cambridge, MA 2011 ConTenTS © 2011, Pierre Menard Gallery Foreword 10 Arrow Street, Cambridge, MA 02138 by John Wronoski 6 Paul* M. Kaestner 74 617 868 20033 / www.pierremenardgallery.com Kahn & Selesnick 78 Editing: Heide Hatry Curator’s Statement Ulrich Klieber 66 Design: Heide Hatry, Joanna Seitz by Heide Hatry 7 Bill Knott 82 All images © the artist Bodo Korsig 84 Foreword © 2011 John Wronoski The Artist’s Book: Rich Kostelanetz 88 Curator’s Statement © 2011 Heide Hatry A Matter of Self-Reflection Christina Kruse 90 The Artist’s Book: A Matter of Self-Reflection © 2011 Thyrza Nichols Goodeve by Thyrza Nichols Goodeve 8 Andrea Lange 92 All rights reserved Nick Lawrence 94 No part of this catalogue Jean-Jacques Lebel 96 may be reproduced in any form Roberta Allen 18 Gregg LeFevre 98 by electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or information storage retrieval Tatjana Bergelt 20 Annette Lemieux 100 without permission in writing from the publisher Elena Berriolo 24 Stephen Lipman 102 Star Black 26 Larry Miller 104 Christine Bofinger 28 Kate Millett 108 Curator’s Acknowledgements Dianne Bowen 30 Roberta Paul 110 My deepest gratitude belongs to Pierre Menard Gallery, the most generous gallery I’ve ever worked with Ian Boyden 32 Jim Peters 112 Dove Bradshaw 36 Raquel Rabinovich 116 I want to acknowledge the writers who have contributed text for the artist’s books Eli Brown 38 Aviva Rahmani 118 Jorge Accame, Walter Abish, Samuel Beckett, Paul Celan, Max Frisch, Sam Hamill, Friedrich Hoelderin, John Keats, Robert Kelly Inge Bruggeman 40 Osmo Rauhala 120 Andreas Koziol, Stéphane Mallarmé, Herbert Niemann, Johann P. -

Drone Music from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Drone music From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Drone music Stylistic origins Indian classical music Experimental music[1] Minimalist music[2] 1960s experimental rock[3] Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments,guitars, string instruments, electronic postproduction equipment Mainstream popularity Low, mainly in ambient, metaland electronic music fanbases Fusion genres Drone metal (alias Drone doom) Drone music is a minimalist musical style[2] that emphasizes the use of sustained or repeated sounds, notes, or tone-clusters – called drones. It is typically characterized by lengthy audio programs with relatively slight harmonic variations throughout each piece compared to other musics. La Monte Young, one of its 1960s originators, defined it in 2000 as "the sustained tone branch of minimalism".[4] Drone music[5][6] is also known as drone-based music,[7] drone ambient[8] or ambient drone,[9] dronescape[10] or the modern alias dronology,[11] and often simply as drone. Explorers of drone music since the 1960s have included Theater of Eternal Music (aka The Dream Syndicate: La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Tony Conrad, Angus Maclise, John Cale, et al.), Charlemagne Palestine, Eliane Radigue, Philip Glass, Kraftwerk, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Sonic Youth,Band of Susans, The Velvet Underground, Robert Fripp & Brian Eno, Steven Wilson, Phill Niblock, Michael Waller, David First, Kyle Bobby Dunn, Robert Rich, Steve Roach, Earth, Rhys Chatham, Coil, If Thousands, John Cage, Labradford, Lawrence Chandler, Stars of the Lid, Lattice, -

Experimental

Experimental Discussão de alguns exemplos Earle Brown ● Earle Brown (December 26, 1926 – July 2, 2002) was an American composer who established his own formal and notational systems. Brown was the creator of open form,[1] a style of musical construction that has influenced many composers since—notably the downtown New York scene of the 1980s (see John Zorn) and generations of younger composers. ● ● Among his most famous works are December 1952, an entirely graphic score, and the open form pieces Available Forms I & II, Centering, and Cross Sections and Color Fields. He was awarded a Foundation for Contemporary Arts John Cage Award (1998). Terry Riley ● Terrence Mitchell "Terry" Riley (born June 24, 1935) is an American composer and performing musician associated with the minimalist school of Western classical music, of which he was a pioneer. His work is deeply influenced by both jazz and Indian classical music, and has utilized innovative tape music techniques and delay systems. He is best known for works such as his 1964 composition In C and 1969 album A Rainbow in Curved Air, both considered landmarks of minimalist music. La Monte Young ● La Monte Thornton Young (born October 14, 1935) is an American avant-garde composer, musician, and artist generally recognized as the first minimalist composer.[1][2][3] His works are cited as prominent examples of post-war experimental and contemporary music, and were tied to New York's downtown music and Fluxus art scenes.[4] Young is perhaps best known for his pioneering work in Western drone music (originally referred to as "dream music"), prominently explored in the 1960s with the experimental music collective the Theatre of Eternal Music. -

The Box As Meeting Place Artistic Encounters in Aspen Magazine (1965-1971)

The Box as Meeting Place Artistic Encounters in Aspen Magazine (1965-1971) 129 Maarten van Gageldonk Aspen was a multimedia magazine, each issue presented as a box full of surpri- ses by artists, writers, thinkers, and unknowns. What kept contributors as diverse as John Lennon, Yoko Ono, J.G. Ballard, and David Hockney together? In 1965 New York magazine editor Phyllis dia revolution. Aspen would return the func- Johnson travelled to Aspen, Colorado, to tion of the magazine to ‘the original meaning partake in the International Design Confe- of the word, as “a storehouse, a cache, a ship rence Aspen (IDCA) and returned home asking laden with stores”’, and in doing so it would herself how the traditional magazine could be liberate it from its linearity and two-dimen- adapted for the modern age. Later that year sionality, as well as from the dominance of she launched her answer: Aspen Magazine, printed matter.1 Accordingly, throughout the the multimedia magazine in a box. Between years Aspen’s slim boxes and folders contained 1965 and 1971 ten issues of Aspen appeared, posters, flip books, newspapers, stamps, a each put together by a different guest editor kite, a miniature sculpture, flexi discs with and devoted to a different theme, ranging music and audio recordings, and in 1967 even from Pop Art and Minimalism to psychedelic a reel of Super 8 film – a first for any magazine. art and Asian culture. Opening one of Aspen’s To its subscribers the contents of each issue boxes now is like unearthing a time capsule came as a surprise and connecting the various and its contributor list reads like a sample items demanded a non-trivial amount of activ- sheet of the 1960s, including work by William ity on the account of the ‘reader’. -

Aldo Tambellini

Aldo Tambellini 11 March - 6 August 2017 A Portrait of Aldo Tambellini, 2010 • Photo: Gerard Malanga Introduction As a key figure in the 1960s underground scene of New York – a missing link between the European avant-garde and the artistic move- ments that followed Abstract Expressionism – Aldo Tambellini (born 1930 in Syracuse, NY, US) is an experimenter, agitator, and a major catalyst of in- novation in the field of multimedia art. Tambellini took the transformational potential of artistic expression that stems from painting and sculpture and brought it to the experiences of Expanded Cinema. After his early experiments with color in the 1950s, the artist em- braced BLACK as an artistic, philosophical, social, and political commit- ment, and started to use mainly this color in his works. The American Civ- il Rights Movement and the struggle for racial equality, the Vietnam War, and the space-age were influences on his visionary oeuvre, unique in that it demonstrates the fragile balance between an artist’s absorption of the stimuli provided by contemporary new technologies and the social and po- litical environment of his time. Attracted above all by the energetic nature of painting, Tambellini transferred a meticulous expression of the language and power of gesture – first onto slides, and later onto film frames and vid- eo. Over the course of the 1960s he created his Black Project from which emerged: the Black Film Series, 16 mm films focused on philosophical and social facets of black; the Black Performances, multimedia performances he called “Electromedia” which are based on his theories of the integration of the arts; the Black Video Series and Black TV, which took his mode of ex- perimentation further into video and television technologies. -

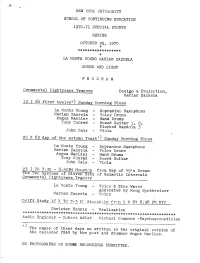

Nyuprogram.Pdf

NEW YORK UNIVERSiTY SCHOOL OF CONTINUING EDUCATION 1970-71 SPECIAL EVENTS SERIES OCTOBER 25, 1970 LA MONTE YOUNG MARIAN ZAZEELA SOUND AND LIGHT P R 0 G R A M Ornamental Lightyears Tracery Design & Projection, Marian Zaz--ela 12 1 64 first twelve+) Sunday Morning Blues La Monte Young - Sopranino Saxophone Marian Zaze--la - Voice Drone Angus MacLise - Hand Drums Tony Conrad. - Bowed Guitar 1, 2, Plucked Mandola 3 John Cale - Viola 20 X 63 day of the autumn feast-0 Sunday Morning Blues La Monte Young Sppranino Saxophone Marian Zaz--ela Voice Drone AngusC=) MacLise Hand Drums Tony Conrad. Bowed Guitax John Cale Viola 23 1 70 7 :35 - 8 :40PM Houston from Map of 49's Dream Th-eTwo Systems of 01-evenSat s of Galactic Intervals Ornamental Lightyears Tracery La, Monte Young - Voice & Sine Waves generated by Moog Synthesizer Maxian Zazeela - Voicea Drift Study 16 X 70 Pt' StockEolm frrm 5 V 67 6 :38 PM NYC Christer Hennix Realization Audio Engineer - Rob-~=rt Adler Michael Commons -Psychoacoustician The names of these days as written in the the original version of calendar YEAR by the pcet and. drummer Angus MacLise . NO PHOTOGRAPHS OR SOUND RECORDINGS PERMITTED . P R 0 G R A M N 0 T E S Ornamental Lightyears Tracery The Projections form part of a series of light works designed for live Performance on three or more slide projectors . The series contains numerous black and white negative and positive photographs of modular sections of several closely related designs . Each slide mount holds a photograph and a combination of colored gals . -

Tuning in Opposition

TUNING IN OPPOSITION: THE THEATER OF ETERNAL MUSIC AND ALTERNATE TUNING SYSTEMS AS AVANT-GARDE PRACTICE IN THE 1960’S Charles Johnson Introduction: The practice of microtonality and just intonation has been a core practice among many of the avant-garde in American 20th century music. Just intonation, or any system of tuning in which intervals are derived from the harmonic series and can be represented by integer ratios, is thought to have been in use as early as 5000 years ago and fell out of favor during the common practice era. A conscious departure from the commonly accepted 12-tone per octave, equal temperament system of Western music, contemporary music created with alternate tunings is often regarded as dissonant or “out-of-tune,” and can be read as an act of opposition. More than a simple rejection of the dominant tradition, the practice of designing scales and tuning systems using the myriad options offered by the harmonic series suggests that there are self-deterministic alternatives to the harmonic foundations of Western art music. And in the communally practiced and improvised performance context of the 1960’s, the use of alternate tunings offers a Johnson 2 utopian path out of the aesthetic dead end modernism had reached by mid-century. By extension, the notion that the avant-garde artist can create his or her own universe of tonality and harmony implies a similar autonomy in defining political and social relationships. In the early1960’s a New York experimental music performance group that came to be known as the Dream Syndicate or the Theater of Eternal Music (TEM) began experimenting with just intonation in their sustained drone performances. -

SHEILA ROSS CV Website: Sheilaross.Co.Uk Email: [email protected]

A.I.R. SHEILA ROSS CV website: sheilaross.co.uk email: [email protected] EDUCATION 2000 Certificate in Multimedia, New York University School of Continuing and Professional Studies, NYC, NY 1985 Masters of Fine Arts in Sculpture, Hunter College CUNY, NYC, NY 1975 Certificate in Advanced Sculpture, St. Martin’s School of Art, London, England 1974 Diploma in Art & Design (B.A.hons., sculpture), St. Martin’s School of Art, London, England GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2017 Ann Pachner’s The Blossom as the Self, guest artist, A.I.R Gallery 2014 On Being, curated by Julie Lohnes, Nott Memorial Gallery, Union College, Schenectady 2013 40/40, 40th Anniversary Exhibition curated by Lilly Wei, A.I.R Gallery 2012 Anomalistic Revolution, curated by Julie Lohnes, A.I.R. Gallery, Brooklyn, NY 2011 But that’s a different story..., three-person show with Daria Dorosh and Jeanette May, A.I.R Gallery and Dumbo Photo Festival, Brooklyn 2011 Vestige: Traces of Reality, curated by Jill Conner, Konsthallen, Sandviken, Sweden and A.I.R Gallery 2010 The Affordable Art Fair, NYC, NY, ArtHampton, Southampton, N.Y. 2009 Third Person Singular: Does Gender Still Matter?, curated by Barbara O'Brien; Art Institute of Boston at Lesley University 2009 In-Sight Photography Center Exhibits and Auctions; Brattleboro, Vermont 2008 Your Documents Please: Museum of Arts and Cras, Itami, Japan; Zaim Artspace, Yokohama, Japan; 2B Galéria, Budapest, Hungary; Galerie Kurt im Hirsch, Berlin, Germany; Galeria Z, Bratislava, Slovakia; Galeria Ajolote Arte Contemporáneo, Guadalajara, Mexico 2008 A.I.R: The History Show: Work by A.I.R Artists from 1972 to the Present: A.I.R Gallery with the Fales Collection, New York University Library 2007 One True Thing: A.I.R in Putney; The Putney School Gallery, Michael S. -

Your Pretty Face Is Going to Hell the Dangerous Glitter of David Bowie, Iggy Pop,And Lou Reed

PF00fr(i-viii;vibl) 9/3/09 4:01 PM Page iii YOUR PRETTY FACE IS GOING TO HELL THE DANGEROUS GLITTER OF DAVID BOWIE, IGGY POP,AND LOU REED Dave Thompson An Imprint of Hal Leonard Corporation New York PF00fr(i-viii;vibl) 9/16/09 3:34 PM Page iv Frontispiece: David Bowie, Iggy Pop, and Lou Reed (with MainMan boss Tony Defries laughing in the background) at the Dorchester Hotel, 1972. Copyright © 2009 by Dave Thompson All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, with- out written permission, except by a newspaper or magazine reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review. Published in 2009 by Backbeat Books An Imprint of Hal Leonard Corporation 7777 West Bluemound Road Milwaukee, WI 53213 Trade Book Division Editorial Offices 19 West 21st Street, New York, NY 10010 Printed in the United States of America Book design by David Ursone Typography by UB Communications Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Thompson, Dave, 1960 Jan. 3- Your pretty face is going to hell : the dangerous glitter of David Bowie, Iggy Pop, and Lou Reed / Dave Thompson. — 1st paperback ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and discography. ISBN 978-0-87930-985-5 (alk. paper) 1. Bowie, David. 2. Pop, Iggy, 1947-3. Reed, Lou. 4. Rock musicians— England—Biography. 5. Punk rock musicians—United States—Biography. I. Title. ML400.T47 2009 782.42166092'2—dc22 2009036966 www.backbeatbooks.com PF00fr(i-viii;vibl) 9/3/09 4:01 PM Page vi PF00fr(i-viii;vibl) 9/3/09 4:01 PM Page vii CONTENTS Prologue . -

64 Doi:10.1162/GREY a 00219 Poster for Aldo Tambellini, Black

Poster for Aldo Tambellini, Black Zero (1965–68), 1965. 64 doi:10.1162/GREY_a_00219 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00219 by guest on 01 October 2021 The Subject of Black: Abstraction and the Politics of Race in the Expanded Cinema Environment NADJA MILLNER-LARSEN Midway through a 2012 reperformance of the expanded cinema event Black Zero (1965–1968)—a collage of jazz improvisation, light projection, poetry reading, dance performance, and televisual noise—the phrases of Calvin C. Hernton’s poem “Jitterbugging in the Streets” reached a crescendo: 1 TERROR is in Harlem A FEAR so constant Black men crawl the pavement as if they were snakes, and snakes turn to sticks that beat the heads of those who try to stand up— A Genocide so blatant Every third child will do the junky-nod in the whore-scented night before semen leaps from his loins— And Fourth of July comes with the blasting bullet in the belly of a teenager Against which no Holyman, no Christian housewife In Edsel automobile Will cry out this year Jitterbugging in the streets. 2 Hernton’s rendering of the 1964 Harlem uprising, originally published as part of the New Jazz Poets record, is gradually engulfed by a bombastic soundscape dominated by an archival recording of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) Apollo 8 launch interspersed with video static and the familiar drone of a vacuum cleaner. Surrounded by black walls spattered with Grey Room 67, Spring 2017, pp. 64–99. © 2017 Grey Room, Inc. and Massachusetts Institute of Technology 65 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00219 by guest on 01 October 2021 slides of slow-rotating abstract spheres whose contours melt into gaseous implo - sions, viewers are stimulated by flashing television monitors, black-and-white projections from hand-painted celluloid, and video images of black children pro - jected onto a glacially expanding black balloon.