We Are the Primitives of a New Era. an Interview with Aldo Tambellini (Part III),” Art Experience: NYC, October 29, 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One of a Kind, Unique Artist's Books Heide

ONE OF A KIND ONE OF A KIND Unique Artist’s Books curated by Heide Hatry Pierre Menard Gallery Cambridge, MA 2011 ConTenTS © 2011, Pierre Menard Gallery Foreword 10 Arrow Street, Cambridge, MA 02138 by John Wronoski 6 Paul* M. Kaestner 74 617 868 20033 / www.pierremenardgallery.com Kahn & Selesnick 78 Editing: Heide Hatry Curator’s Statement Ulrich Klieber 66 Design: Heide Hatry, Joanna Seitz by Heide Hatry 7 Bill Knott 82 All images © the artist Bodo Korsig 84 Foreword © 2011 John Wronoski The Artist’s Book: Rich Kostelanetz 88 Curator’s Statement © 2011 Heide Hatry A Matter of Self-Reflection Christina Kruse 90 The Artist’s Book: A Matter of Self-Reflection © 2011 Thyrza Nichols Goodeve by Thyrza Nichols Goodeve 8 Andrea Lange 92 All rights reserved Nick Lawrence 94 No part of this catalogue Jean-Jacques Lebel 96 may be reproduced in any form Roberta Allen 18 Gregg LeFevre 98 by electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or information storage retrieval Tatjana Bergelt 20 Annette Lemieux 100 without permission in writing from the publisher Elena Berriolo 24 Stephen Lipman 102 Star Black 26 Larry Miller 104 Christine Bofinger 28 Kate Millett 108 Curator’s Acknowledgements Dianne Bowen 30 Roberta Paul 110 My deepest gratitude belongs to Pierre Menard Gallery, the most generous gallery I’ve ever worked with Ian Boyden 32 Jim Peters 112 Dove Bradshaw 36 Raquel Rabinovich 116 I want to acknowledge the writers who have contributed text for the artist’s books Eli Brown 38 Aviva Rahmani 118 Jorge Accame, Walter Abish, Samuel Beckett, Paul Celan, Max Frisch, Sam Hamill, Friedrich Hoelderin, John Keats, Robert Kelly Inge Bruggeman 40 Osmo Rauhala 120 Andreas Koziol, Stéphane Mallarmé, Herbert Niemann, Johann P. -

Aldo Tambellini

Aldo Tambellini 11 March - 6 August 2017 A Portrait of Aldo Tambellini, 2010 • Photo: Gerard Malanga Introduction As a key figure in the 1960s underground scene of New York – a missing link between the European avant-garde and the artistic move- ments that followed Abstract Expressionism – Aldo Tambellini (born 1930 in Syracuse, NY, US) is an experimenter, agitator, and a major catalyst of in- novation in the field of multimedia art. Tambellini took the transformational potential of artistic expression that stems from painting and sculpture and brought it to the experiences of Expanded Cinema. After his early experiments with color in the 1950s, the artist em- braced BLACK as an artistic, philosophical, social, and political commit- ment, and started to use mainly this color in his works. The American Civ- il Rights Movement and the struggle for racial equality, the Vietnam War, and the space-age were influences on his visionary oeuvre, unique in that it demonstrates the fragile balance between an artist’s absorption of the stimuli provided by contemporary new technologies and the social and po- litical environment of his time. Attracted above all by the energetic nature of painting, Tambellini transferred a meticulous expression of the language and power of gesture – first onto slides, and later onto film frames and vid- eo. Over the course of the 1960s he created his Black Project from which emerged: the Black Film Series, 16 mm films focused on philosophical and social facets of black; the Black Performances, multimedia performances he called “Electromedia” which are based on his theories of the integration of the arts; the Black Video Series and Black TV, which took his mode of ex- perimentation further into video and television technologies. -

64 Doi:10.1162/GREY a 00219 Poster for Aldo Tambellini, Black

Poster for Aldo Tambellini, Black Zero (1965–68), 1965. 64 doi:10.1162/GREY_a_00219 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00219 by guest on 01 October 2021 The Subject of Black: Abstraction and the Politics of Race in the Expanded Cinema Environment NADJA MILLNER-LARSEN Midway through a 2012 reperformance of the expanded cinema event Black Zero (1965–1968)—a collage of jazz improvisation, light projection, poetry reading, dance performance, and televisual noise—the phrases of Calvin C. Hernton’s poem “Jitterbugging in the Streets” reached a crescendo: 1 TERROR is in Harlem A FEAR so constant Black men crawl the pavement as if they were snakes, and snakes turn to sticks that beat the heads of those who try to stand up— A Genocide so blatant Every third child will do the junky-nod in the whore-scented night before semen leaps from his loins— And Fourth of July comes with the blasting bullet in the belly of a teenager Against which no Holyman, no Christian housewife In Edsel automobile Will cry out this year Jitterbugging in the streets. 2 Hernton’s rendering of the 1964 Harlem uprising, originally published as part of the New Jazz Poets record, is gradually engulfed by a bombastic soundscape dominated by an archival recording of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) Apollo 8 launch interspersed with video static and the familiar drone of a vacuum cleaner. Surrounded by black walls spattered with Grey Room 67, Spring 2017, pp. 64–99. © 2017 Grey Room, Inc. and Massachusetts Institute of Technology 65 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00219 by guest on 01 October 2021 slides of slow-rotating abstract spheres whose contours melt into gaseous implo - sions, viewers are stimulated by flashing television monitors, black-and-white projections from hand-painted celluloid, and video images of black children pro - jected onto a glacially expanding black balloon. -

The Convergence of Video, Art and Television at WGBH (1969)

The Medium is the Medium: the Convergence of Video, Art and Television at WGBH (1969). By James A. Nadeau B.F.A. Studio Art Tufts University, 2001 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEPTEMBER 2006 ©2006 James A. Nadeau. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known of hereafter created. Signature of Author: ti[ - -[I i Department of Comparative Media Studies August 11, 2006 Certified by: v - William Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies JThesis Supervisor Accepted by: - v William Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies OF TECHNOLOGY SEP 2 8 2006 ARCHIVES LIBRARIES "The Medium is the Medium: the Convergence of Video, Art and Television at WGBH (1969). "The greatest service technology could do for art would be to enable the artist to reach a proliferating audience, perhaps through TV, or to create tools for some new monumental art that would bring art to as many men today as in the middle ages."I Otto Piene James A. Nadeau Comparative Media Studies AUGUST 2006 Otto Piene, "Two Contributions to the Art and Science Muddle: A Report on a symposium on Art and Science held at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, March 20-22, 1968," Artforum Vol. VII, Number 5, January 1969. p. 29. INTRODUCTION Video, n. "That which is displayed or to be displayed on a television screen or other cathode-ray tube; the signal corresponding to this." Oxford English Dictionary, 2006. -

Aldo Tambellini

ALDO TAMBELLINI 1930 Syracuse, NY Raised in Lucca, Italy Lives and works in in Boston, MA EDUCATION 1956-1958 MFA, Sculpture, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 1955-1956 Graduate School of Architecture & Allied Arts, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 1950-1955 B.F.A. (cum laude), Painting, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY 1941-1945 Art Institute, Lucca, Italy ACADEMIC AND PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 1977 Director, Media-Environmental Workshop, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL 1976-1984 Fellow, Center for Advanced Visual Studies, MIT, Cambridge, MA 1976 Visiting Artist, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL 1970-1972 Director, Pilot Program in Video in Harlem, New York Department of Education, New York, NY 1969-1970 Television Artist-in-Residence, Creative Video Tape Recording Project, New York State Department of Education, New York, NY 1964-1965 Sculpture Instructor, Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, NY 1959-1963 Painting and Sculpture Instructor, Marymount Manhattan College, New York, NY PRIZES, AWARDS, DISTINCTIONS 2010 Awarded Gold Medal from the Italian Government, Lucchesi Nel Mondo Organization, in recognition of his lifetime achievement in the Arts 2009 Featured Artist, Film and Video Retrospective, April 27-May 22, 2009. International Media Festival 2009, Osnabruck, Germany 2007 Awarded Lifetime Achievement Award, Aldo Tambellini: Film and Video Retrospective, Syracuse Film and Video Festival, Syracuse, NY 2006 Winner, Experimental Film Short, for Listen, Syracuse International Film and Video Festival, -

The Prehension of Painting

DOCUMENT UFD023 Ina Blom Becoming Video (The Prehension of Painting) In this edited extract from her new book The Autobiography of Video: The Life and Times of a Memory Technology, Ina Blom examines the memory and history of early analog video, and investigates how the medium, heralding new forms of technological and social life, URBANOMIC / DOCUMENTS prehended the forms and forces of painting. URBANOMIC.COM Memories of Painting phenomenon that psychologists call ‘iconic image- ry’, referring to the fact that images are retained by ‘Someone started talking about video history: “Video the brain in complete and full detail for as long as a may be the only art form ever to have a history be- second after their exposure. We assume that these fore it had a history.”’1 This is Bill Viola, recalling a are live images of the world, whereas they are in fact dinner scene at Chinese restaurant in New York on some sort of retention or ‘recording’. For Viola, this a February evening in 1974. Only a few weeks ear- opened up new and confusing avenues of thought. lier—by most accounts an early date in the history Where did memory begin and stimulus end? Were of video art—the Everson Museum in Syracuse had all images always already memories? Was memory opened the first retrospective exhibition of the work actually a future-oriented filter rather than a sense of Nam June Paik, accompanied by a catalogue with of the past—a process of continual invention at the Paik’s reprinted notes, letters, and published writings service of present action? in a messy facsimile format that at once managed to give the impression of instantaneous access to a Such thoughts not only presented human mem- work in progress and of archival findings attesting ory—‘the other half of the equation of technical to some hallowed moment in the past. -

A Rebel, Between Past and Future Published on Iitaly.Org (

A rebel, between past and future Published on iItaly.org (http://108.61.128.93) A rebel, between past and future Letizia Airos Soria (September 23, 2007) You could listen to him for hours, days on end; his words are of an intense existence. Aldo Tambellini relates pieces of his life and lets himself take off on a roll, only slowed down by his companion, Anna, who, tirelessly tries to sort everything out. ... ... But his are thoughts of freedom, memories, acknowledgements, and reflections. He wants to talk about the past, the future, everything. Maybe even the Universe. Aldo is like this, every time you meet him he manages to sweep you away. He involves you. A retrospective on Aldo will be held in a few days in Lucca, a very important first in Italy. I contacted him to get his impressions on his return to his origins, the city where he spent his infancy and Page 1 of 4 A rebel, between past and future Published on iItaly.org (http://108.61.128.93) adolescence. I try to grasp his feelings, emotions and above all his recollections. It is like an overflowing river. It’s impossible to embank him, you follow him and you become a stone being slammed from one bank to the other. And yet there is something more profound that goes beyond his way of communicating, his American being but also his indissoluble ties to Italy. His artistic and human path is a burning fire of constant rebellion. He’s a man ready to feel - not just artistically - the responsibility to contest those that which others know only to accept. -

OTTO PIENE Biography

SPERONE WESTWATER 257 Bowery New York 10002 T + 1 212 999 7337 F + 1 212 999 7338 www.speronewestwater.com OTTO PIENE Biography 1928 Born Laasphe, Westphalia, Germany. Lived and worked in Düsseldorf, Cambridge, and Groton, Massachusetts. 2014 Died Berlin, Germany. Education 1948-50 Degree in painting, Blocherer Art School and the Academy of Art, Munich, Germany. 1950-53 Degree in art education, Staatliche Kunstakademie, Düsseldorf, Germany. 1953-57 State Examination in philosophy, University of Cologne, Germany. 1964 Artist-in-residence, Graduate School of Fine Arts, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Early History (1950s-1960s) 1957 Founds group ZERO with Heinz Mack in Düsseldorf; Günther Uecker joins 1959 First public performance of “Light Ballet” 1964 Produces play “Die Feuerblume” (“The Fire Flower”) at the Theater Diogenes, Berlin, Germany 1966 Group ZERO splits up; final common exhibition with Heinz Mack and Günther Uecker in Bonn, Germany Founded the Black Gate (first electromedia theater) with Aldo Tambellini in New York 1968-1969 Produces “Black Gate Cologne” (first live television production by artists) with Aldo Tambellini at the TV studio WDR III 1969 Coins the term “Sky Art” for large outdoor sky/light projects “Manned Helium Sculpture” for “Electronic Light Ballet,” NET-TV Produces project for “The Medium Is the Medium” television program Appointments and Lectures 1964 Visiting Professor, Graduate School of Art, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Lectures at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London, the Art -

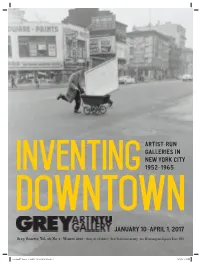

Inventing Downtown

ARTIST-RUN GALLERIES IN NEW YORK CITY Inventing 1952–1965 Downtown JANUARY 10–APRIL 1, 2017 Grey Gazette, Vol. 16, No. 1 · Winter 2017 · Grey Art Gallery New York University 100 Washington Square East, NYC InventingDT_Gazette_9_625x13_12_09_2016_UG.indd 1 12/13/16 2:15 PM Danny Lyon, 79 Park Place, from the series The Destruction of Lower Manhattan, 1967. Courtesy the photographer and Magnum Photos Aldo Tambellini, We Are the Primitives of a New Era, from the Manifesto series, c. 1961. JOIN THE CONVERSATION @NYUGrey InventingDowntown # Aldo Tambellini Archive, Salem, Massachusetts This issue of the Grey Gazette is funded by the Oded Halahmy Endowment for the Arts; the Boris Lurie Art Foundation; the Foundation for the Arts. Inventing Downtown: Artist-Run Helen Frankenthaler Foundation; the Art Dealers Association Galleries in New York City, 1952–1965 is organized by the Grey Foundation; Ann Hatch; Arne and Milly Glimcher; The Cowles Art Gallery, New York University, and curated by Melissa Charitable Trust; and the Japan Foundation. The publication Rachleff. Its presentation is made possible in part by the is supported by a grant from Furthermore: a program of the generous support of the Terra Foundation for American Art; the J.M. Kaplan Fund. Additional support is provided by the Henry Luce Foundation; The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Grey Art Gallery’s Director’s Circle, Inter/National Council, and Visual Arts; the S. & J. Lurje Memorial Foundation; the National Friends; and the Abby Weed Grey Trust. GREY GAZETTE, VOL. 16, NO. 1, WINTER 2017 · PUBLISHED BY THE GREY ART GALLERY, NYU · 100 WASHINGTON SQUARE EAST, NYC 10003 · TEL. -

Radsoftwareno1.Pdf

D 0 ditioned rather than asserting the implicit immediacy of video, immunizing us to the impact of t there is information by asking us to anticipate what already can be anticipated-the nightly current dinnertime Vietnam reports to serialized single format shows. If information is our Please enclose information pertaining to the followinp : environment, why isn't our environment considered information? Personal Biography (publishable and for use in our own n choice So six months ago some of us who have been working in videotape got the idea for an files, i .e designs information source which would bring together people who were already making their ., resume type information, past activities to the own television, attempt to turn on others to the .idea as a means of social change and prior to video, or simultaneous with, etc .) . [one not exchange, and serve as an introduction to an evolving handbook of technology . 2 . Experimentation a people with video . a . Why are you using video? Our working title was The Video Newsletter and the information herein was gathered How long have you been mainly from people who responded to the questionaire at right. While some of the using it? resulting contents may seem unnecessarily hardware-oriented or even esoteric, we felt b . 'What experiments have you made, are you presently that thrusting into the public space the concept of practical software design as social tool through could not wait. making, and do you plan to make with this medium? ;eem like C . Where do you see yourself going with,video (in tuation" In future issues we plan to continue incorporating reader feedback to relationship to both possible make this a process hardware and software aspects)? rather than a product publication . -

Video: a Selected Chronology, 1963-1983

Video: A Selected Chronology, 1963-1983 By Barbara London The chronology that follows highlights some of the major events that have helped to shape independent video in the United States. Although institutions 'rave provided the context for video, it is he artists' contributions that are of the ~reatest importance. 1963 Exhibitions/Events New York. Television De-Coli/age by WolfVostell, Smolin Gallery. First U.S. environmental installation using a tele vision set. 1964 Television/Productions Boston. Jazz Images, WGBH-TV. Producer, Fred Barzyk. Five short -isualizations of music for broadcast; me of the first attempts at experimental television. 1965 Exhibitions/Events New York. Electronic Art by Nam June Downloaded by [George Washington University] at 20:00 03 February 2015 Paik, Galeria Bonino. Artist's first gal lery exhibition in U.S. New Cinema Festival I (Expanded Cinema Festival), The Film-Makers Cinematheque. Organized by John Brockman. Festival explores uses of mixed-media projection, including vid eo,sound, and light experiments. 966 xhibitions/Events ew York. 9 Evenings: Theater and ngineering, 69th Regiment Armory. rganized by Billy Kliiver. Mixed edia performance events with collabo ation between ten artists and forty ngineers. Video projection used in ,. orks of Alex Hay, Robert Rauschen rg, David Tudor, Robert Whitman. elma Last Year by Ken Dewey, New Bruce Nauman, Live Taped Video Corridor, 1969-70. Installation at the Whitney ork Film Festival at Lincoln Center, Museum, New York. Fall 1985 249 Philharmonic Hall Lobby. Multichan of Art. 1969 nel video installation with photographs The Machine as Seen at the End ofthe Exhibitions/Events by Bruce Davidson, music by Terry Mechanical Age, The Museum of Mod Riley. -

Aldo Tambellini

LIVE ALDO TAMBELLINI RETRACING BLACK 1971, multimedia concert, International Institute, 1971, 0 + Aldo Tambellini and Franklin Morris with Membrain Studio Automation House, New York 9–14 OCtobeR 2012 FREE Related EVentS: SCREENING SatURdaY 13 OCtobeR 18.00, StaRR AUditoRIUM £5, CONCESSionS AVailable PERFORMANCE SatURdaY 13 OCtobeR 21.00, THE TanKS £10, CONCESSionS AVailable AS PART of THE TanKS at Tate ModeRN Fifteen WeeKS of ART in ACtion 18 JULy – 28 OCtobeR 2012 Black to me is like a beginning. A beginning of what it wants to be Cologne television studio. The footage was edited and then broadcast rather than what it does not want to be. I am not discussing black as a in January 1969, tradition or non-tradition in painting or as having anything to do with making it the first full-scale work of art for broadcast television. pigment or as an opposition to colour. As I am working and exploring For Retracing Black, a triptych of hand-painted 16mm films black in different kinds of dimensions, I’m definitely more and more belonging to the Black Film Series is featured along with unreleased convinced that black is actually the beginning of everything, which works filmed by the artist in 1960s New York, while a series of the art concept is not. Black gets rid of the historical definition. Black projected Lumagrams transforms cellular forms into a sculptural, kinetic is a state of being blind and more aware. Black is a oneness with installation. Electronic sound compositions are intertwined with the birth. Black is within totality, the oneness of all.