Renegade Poetics (Or, Would Black Aesthetics by An[Y J Other Name Be

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ishmael Reed Interviewed

Boxing on Paper: Ishmael Reed Interviewed by Don Starnes [email protected] http://www.donstarnes.com/dp/ Don Starnes is an award winning Director and Director of Photography with thirty years of experience shooting in amazing places with fascinating people. He has photographed a dozen features, innumerable documentaries, commercials, web series, TV shows, music and corporate videos. His work has been featured on National Geographic, Discovery Channel, Comedy Central, HBO, MTV, VH1, Speed Channel, Nerdist, and many theatrical and festival screens. Ishmael Reed [in the white shirt] in New Orleans, Louisiana, September 2016 (photo by Tennessee Reed). 284 Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol.10. no.1, March 2017 Editor’s note: Here author (novelist, essayist, poet, songwriter, editor), social activist, publisher and professor emeritus Ishmael Reed were interviewed by filmmaker Don Starnes during the 2014 University of California at Merced Black Arts Movement conference as part of an ongoing film project documenting powerful leaders of the Black Arts and Black Power Movements. Since 2014, Reed’s interview was expanded to take into account the presidency of Donald Trump. The title of this interview was supplied by this publication. Ishmael Reed (b. 1938) is the winner of the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship (genius award), the renowned L.A. Times Robert Kirsch Lifetime Achievement Award, the Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a Rosenthal Family Foundation Award from the National Institute for Arts and Letters. He has been nominated for a Pulitzer and finalist for two National Book Awards and is Professor Emeritus at the University of California at Berkeley (a thirty-five year presence); he has also taught at Harvard, Yale and Dartmouth. -

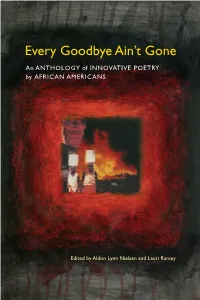

Every Goodbye Ain't Gone

Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone An ANTHOLOGY of INNOVATIVE POETRY by AFRICAN AMERICANS Edited by Aldon Lynn Nielsen and Lauri Ramey Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone You are reading copyrighted material published by the University of Alabama Press. Any posting, copying, or distributing of this work beyond fair use as defined under U.S. Copyright law is illegal and injures the author and publisher. For permission to reuse this work, contact the University of Alabama Press. MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY POETICS Series Editors Charles Bernstein Hank Lazer Series Advisory Board Maria Damon Rachel Blau DuPlessis Alan Golding Susan Howe Nathaniel Mackey Jerome McGann Harryette Mullen Aldon Nielsen Marjorie Perloff Joan Retallack Ron Silliman Lorenzo Thomas Jerr y Ward You are reading copyrighted material published by the University of Alabama Press. Any posting, copying, or distributing of this work beyond fair use as defined under U.S. Copyright law is illegal and injures the author and publisher. For permission to reuse this work, contact the University of Alabama Press. Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone An Anthology of Innovative Poetry by African Americans Edited by ALDON LYNN NIELSEN and LAURI RAMEY THE UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA PRESS Tuscaloosa You are reading copyrighted material published by the University of Alabama Press. Any posting, copying, or distributing of this work beyond fair use as defined under U.S. Copyright law is illegal and injures the author and publisher. For permission to reuse this work, contact the University of Alabama Press. Copyright © 2006 The University of Alabama Press Tuscaloosa, Alabama 35487-0380 All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Typeface: Janson Text ∞ The paper on which this book is printed meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. -

The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry Howard Rambsy II The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor First paperback edition 2013 Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2011 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 5432 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rambsy, Howard. The black arts enterprise and the production of African American poetry / Howard Rambsy, II. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-472-11733-8 (cloth : acid-free paper) 1. American poetry—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Poetry—Publishing—United States—History—20th century. 3. African Americans—Intellectual life—20th century. 4. African Americans in literature. I. Title. PS310.N4R35 2011 811'.509896073—dc22 2010043190 ISBN 978-0-472-03568-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12005-5 (e-book) Cover illustrations: photos of writers (1) Haki Madhubuti and (2) Askia M. Touré, Mari Evans, and Kalamu ya Salaam by Eugene B. Redmond; other images from Shutterstock.com: jazz player by Ian Tragen; African mask by Michael Wesemann; fist by Brad Collett. -

Introduction Writer Biographies for B&N Classics A. Michael Matin Is a Professor in the English Department of Warren Wilson

Introduction Writer Biographies for B&N Classics A. Michael Matin is a professor in the English Department of Warren Wilson College, where he teaches late-nineteenth-century and twentieth-century British and Anglophone postcolonial literature. His essays have appeared in Studies in the Novel, The Journal of Modern Literature, Scribners’ British Writers, Scribners’ World Poets, and the Norton Critical Edition of Kipling’s Kim. Matin wrote Introductions and Notes for Conrad’s Lord Jim and Heart of Darkness and Selected Short Fiction. Alfred Mac Adam, Professor at Barnard College–Columbia University, teaches Latin American and comparative literature. He is a translator of Latin American fiction and writes extensively on art. He has written an Introductions and Notes for H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine and The Invisible Man and The War of the Worlds, Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’ Les Liasons Dangereuses, and Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey. Amanda Claybaugh is Associate Professor of English and comparative literature at Columbia University. She is currently at work on a project that considers the relation between social reform and the literary marketplace in the nineteenth-century British and American novel. She has written an Introductions and Notes for Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. Amy Billone is Assistant Professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville where her specialty is 19th Century British literature. She is the author of Little Songs: Women, Silence and the Nineteenth-Century Sonnet and has published articles on both children’s literature and poetry in numerous places. She wrote the Introduction and Notes for Peter Pan by J. -

Women's History Is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating in Communities

Women’s History is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating In Communities A How-To Community Handbook Prepared by The President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History “Just think of the ideas, the inventions, the social movements that have so dramatically altered our society. Now, many of those movements and ideas we can trace to our own founding, our founding documents: the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. And we can then follow those ideas as they move toward Seneca Falls, where 150 years ago, women struggled to articulate what their rights should be. From women’s struggle to gain the right to vote to gaining the access that we needed in the halls of academia, to pursuing the jobs and business opportunities we were qualified for, to competing on the field of sports, we have seen many breathtaking changes. Whether we know the names of the women who have done these acts because they stand in history, or we see them in the television or the newspaper coverage, we know that for everyone whose name we know there are countless women who are engaged every day in the ordinary, but remarkable, acts of citizenship.” —- Hillary Rodham Clinton, March 15, 1999 Women’s History is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating In Communities A How-To Community Handbook prepared by the President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History Commission Co-Chairs: Ann Lewis and Beth Newburger Commission Members: Dr. Johnnetta B. Cole, J. Michael Cook, Dr. Barbara Goldsmith, LaDonna Harris, Gloria Johnson, Dr. Elaine Kim, Dr. -

William J. Maxwell Curriculum Vitae August 2021

William J. Maxwell curriculum vitae August 2021 Professor of English and African and African-American Studies Washington University in St. Louis 1 Brookings Drive St. Louis, MO 63130-4899 U.S.A. Phone: (217) 898-0784 E-mail: [email protected] _________________________________________ Education: DUKE UNIVERSITY, DURHAM, NC. Ph.D. in English Language and Literature, 1993. M.A. in English Language and Literature, 1987. COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, NEW YORK, NY. B.A. in English Literature, cum laude, 1984. Academic Appointments: WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS, MO. Professor of English and African and African-American Studies, 2015-. Director of English Undergraduate Studies, 2018- 21. Faculty Affiliate, American Culture Studies, 2011-. Director of English Graduate Studies, 2012-15. Associate Professor of English and African and African-American Studies, 2009-15. UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN, IL. Associate Professor of English and the Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory, 2000-09. Director of English Graduate Studies, 2003-06. Assistant Professor of English and Afro-American Studies, 1994-2000. COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY, WILLIAMSBURG, VA. Visiting Assistant Professor of English, 1996-97. UNIVERSITY OF GENEVA, GENEVA, SWITZERLAND. Assistant (full-time lecturer) in American Literature and Civilization, 1992-94. Awards, Fellowships, and Professional Distinctions: Claude McKay’s lost novel Romance in Marseille, coedited with Gary Edward Holcomb, named one of the ten best books of 2020 by New York Magazine, 2021. Appointed to the Editorial Board of James Baldwin Review, 2019-. Elected Second Vice President (and thus later President) of the international Modernist Studies Association (MSA), 2018; First Vice President, 2019-20; President, 2021-. American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation for my 2015 book F.B. -

The Poetry of Rita Dove

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Winter 1999 Language's "bliss of unfolding" in and through history, autobiography and myth: The poetry of Rita Dove Carol Keyes University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Keyes, Carol, "Language's "bliss of unfolding" in and through history, autobiography and myth: The poetry of Rita Dove" (1999). Doctoral Dissertations. 2107. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2107 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMi films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

CLEAGE, PEARL. Pearl Cleage Papers, 1949-2011

CLEAGE, PEARL. Pearl Cleage papers, 1949-2011 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Collection Stored Off-Site All or portions of this collection are housed off-site. Materials can still be requested but researchers should expect a delay of up to two business days for retrieval. Descriptive Summary Creator: Cleage, Pearl. Title: Pearl Cleage papers, 1949-2011 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1223 Extent: 74.75 linear feet (156 boxes), 12 oversized papers boxes (OP), 4 extra- oversized papers (XOP), 1 oversized bound volume (OBV), AV Masters: 6 linear feet (6 boxes), and 1.41 GB born digital materials (564 files) Abstract: Personal papers of African American novelist and playwright Pearl Cleage including correspondence, manuscript and typescript writings, subject files, professional papers, printed material, photographs, writings by others, and audiovisual material. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Series 1: Personal journals are closed to researchers until December 2037. Series 2: Due to privacy concerns, some material has been redacted. Series 3: Due to privacy concerns, some material has been redacted. Series 4: Professional papers are closed to researchers until December 2037. Collection stored off-site. Researchers must contact the Rose Library in advance to access this collection. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Pearl Cleage papers, 1949-2011 Manuscript Collection No. -

Virginia: Birthplace of America

VIRGINIA: BIRTHPLACE OF AMERICA Over the past 400 years AMERICAN EVOLUTION™ has been rooted in Virginia. From the first permanent American settlement to its cultural diversity, and its commerce and industry, Virginia has long been recognized as the birthplace of our nation and has been influential in shaping our ideals of democracy, diversity and opportunity. • Virginia is home to numerous national historic sites including Jamestown, Mount Vernon, Monticello, Montpelier, Colonial Williamsburg, Arlington National Cemetery, Appomattox Court House, and Fort Monroe. • Some of America’s most prominent patriots, and eight U.S. Presidents, were Virginians – George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, Zachary Taylor, and Woodrow Wilson. • Virginia produced explorers and innovators such as Lewis & Clark, pioneering physician Walter Reed, North Pole discoverer Richard Byrd, and Tuskegee Institute founder Booker T. Washington, all whose genius and dedication transformed America. • Bristol, Virginia is recognized as the birthplace of country music. • Virginia musicians Maybelle Carter, June Carter Cash, Ella Fitzgerald, Patsy Cline, and the Statler Brothers helped write the American songbook, which today is interpreted by the current generation of Virginian musicians such as Bruce Hornsby, Pharrell Williams, and Missy Elliot. • Virginia is home to authors such as Willa Cather, Anne Spencer, Russell Baker, and Tom Wolfe, who captured distinctly American stories on paper. • Influential women who hail from the Commonwealth include Katie Couric, Sandra Bullock, Wanda Sykes, and Shirley MacLaine. • Athletes from Virginia – each who elevated the standards of their sport – include Pernell Whitaker, Moses Malone, Fran Tarkenton, Sam Snead, Wendell Scott, Arthur Ashe, Gabrielle Douglas, and Francena McCorory. -

64 Doi:10.1162/GREY a 00219 Poster for Aldo Tambellini, Black

Poster for Aldo Tambellini, Black Zero (1965–68), 1965. 64 doi:10.1162/GREY_a_00219 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00219 by guest on 01 October 2021 The Subject of Black: Abstraction and the Politics of Race in the Expanded Cinema Environment NADJA MILLNER-LARSEN Midway through a 2012 reperformance of the expanded cinema event Black Zero (1965–1968)—a collage of jazz improvisation, light projection, poetry reading, dance performance, and televisual noise—the phrases of Calvin C. Hernton’s poem “Jitterbugging in the Streets” reached a crescendo: 1 TERROR is in Harlem A FEAR so constant Black men crawl the pavement as if they were snakes, and snakes turn to sticks that beat the heads of those who try to stand up— A Genocide so blatant Every third child will do the junky-nod in the whore-scented night before semen leaps from his loins— And Fourth of July comes with the blasting bullet in the belly of a teenager Against which no Holyman, no Christian housewife In Edsel automobile Will cry out this year Jitterbugging in the streets. 2 Hernton’s rendering of the 1964 Harlem uprising, originally published as part of the New Jazz Poets record, is gradually engulfed by a bombastic soundscape dominated by an archival recording of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) Apollo 8 launch interspersed with video static and the familiar drone of a vacuum cleaner. Surrounded by black walls spattered with Grey Room 67, Spring 2017, pp. 64–99. © 2017 Grey Room, Inc. and Massachusetts Institute of Technology 65 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00219 by guest on 01 October 2021 slides of slow-rotating abstract spheres whose contours melt into gaseous implo - sions, viewers are stimulated by flashing television monitors, black-and-white projections from hand-painted celluloid, and video images of black children pro - jected onto a glacially expanding black balloon. -

Social Issues—United States. Updated July 2014. MLA 6Th Edition

Social Issues—United States. Updated July 2014. MLA 6th edition. Paul Revere Williams Project. Art Museum of the University of Memphis. "200 Negro Workers Walk Off Jobs at BMI Plant Today." Las Vegas Evening Review-Journal Wednesday, October 20 1943, sec. A1:. "2004 Eleven most endangered (La Concha." Preserve Nevada. 2008. 5/6/2008 <http://preservenevada.unlv.edu>. Abrams, Charles. "The Housing Problem and the Negro." Daedalus: Journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 95.1 (1966): 64-76. "Abstracts of Papers Presented at the Twenty-Seventh Annual Meeting of the Society of Architectural Historians (Dozier, Richard K. "Black Craftsmen and Architects in History")." Journal of Architectural Historians 33.3 (1974): 225-243. "Ad for Castaic Country Club." California Eagle May 16 1924: 12. "Ad for Insurance Company." Ebony 15.1 (1959): 137. Adams, Michael. "The Incomparable Success of Paul R. Williams." African American Architects in Current Practice. Ed. Jack Travis. 1st ed. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1991. 20-21. "African Church to Build $1 Million Edifice here: 500 Will use $100 Shovels to Break Ground for Center at Ceremony Sunday (AME Church)." Los Angeles Times August 3 1963, sec. 15:. "America's 100 Richest Negroes: Many Solid Gold Millionaires are among Top Moneymakers in Business." Ebony 17.7 (1962): 130-135. Anderson, Susan. "A City Called Heaven: Black Enchantment and Despair in Los Angeles." The City: Los Angeles and Urban Theory at the End of the Twentieth Century. Ed. Allen J. Scott and Edward W. Soja. 1st paperback ed. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1996, 1998. -

The Works and Critical Reception of Dorothy West

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2005 Renaissance Woman: The Works and Critical Reception of Dorothy West Tamara Jenelle Williamson University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Williamson, Tamara Jenelle, "Renaissance Woman: The Works and Critical Reception of Dorothy West. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2005. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2538 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Tamara Jenelle Williamson entitled "Renaissance Woman: The Works and Critical Reception of Dorothy West." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Miriam Thaggert, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mary E. Papke, Nancy Goslee Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Tamara Jenelle Williamson entitled “Renaissance Woman: The Works and Critical Reception of Dorothy West.” I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English.