Gwendolyn Brooks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry Howard Rambsy II The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor First paperback edition 2013 Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2011 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 5432 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rambsy, Howard. The black arts enterprise and the production of African American poetry / Howard Rambsy, II. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-472-11733-8 (cloth : acid-free paper) 1. American poetry—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Poetry—Publishing—United States—History—20th century. 3. African Americans—Intellectual life—20th century. 4. African Americans in literature. I. Title. PS310.N4R35 2011 811'.509896073—dc22 2010043190 ISBN 978-0-472-03568-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12005-5 (e-book) Cover illustrations: photos of writers (1) Haki Madhubuti and (2) Askia M. Touré, Mari Evans, and Kalamu ya Salaam by Eugene B. Redmond; other images from Shutterstock.com: jazz player by Ian Tragen; African mask by Michael Wesemann; fist by Brad Collett. -

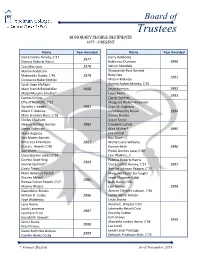

Honorary Degree Recipients 1977 – Present

Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Claire Collins Harvey, C‘37 Harry Belafonte 1977 Patricia Roberts Harris Katherine Dunham 1990 Toni Morrison 1978 Nelson Mandela Marian Anderson Marguerite Ross Barnett Ruby Dee Mattiwilda Dobbs, C‘46 1979 1991 Constance Baker Motley Miriam Makeba Sarah Sage McAlpin Audrey Forbes Manley, C‘55 Mary French Rockefeller 1980 Jesse Norman 1992 Mabel Murphy Smythe* Louis Rawls 1993 Cardiss Collins Oprah Winfrey Effie O’Neal Ellis, C‘33 Margaret Walker Alexander Dorothy I. Height 1981 Oran W. Eagleson Albert E. Manley Carol Moseley Braun 1994 Mary Brookins Ross, C‘28 Donna Shalala Shirley Chisholm Susan Taylor Eleanor Holmes Norton 1982 Elizabeth Catlett James Robinson Alice Walker* 1995 Maya Angelou Elie Wiesel Etta Moten Barnett Rita Dove Anne Cox Chambers 1983 Myrlie Evers-Williams Grace L. Hewell, C‘40 Damon Keith 1996 Sam Nunn Pinkie Gordon Lane, C‘49 Clara Stanton Jones, C‘34 Levi Watkins, Jr. Coretta Scott King Patricia Roberts Harris 1984 Jeanne Spurlock* Claire Collins Harvey, C’37 1997 Cicely Tyson Bernice Johnson Reagan, C‘70 Mary Hatwood Futrell Margaret Taylor Burroughs Charles Merrill Jewel Plummer Cobb 1985 Romae Turner Powell, C‘47 Ruth Davis, C‘66 Maxine Waters Lani Guinier 1998 Gwendolyn Brooks Alexine Clement Jackson, C‘56 William H. Cosby 1986 Jackie Joyner Kersee Faye Wattleton Louis Stokes Lena Horne Aurelia E. Brazeal, C‘65 Jacob Lawrence Johnnetta Betsch Cole 1987 Leontyne Price Dorothy Cotton Earl Graves Donald M. Stewart 1999 Selma Burke Marcelite Jordan Harris, C‘64 1988 Pearl Primus Lee Lorch Dame Ruth Nita Barrow Jewel Limar Prestage 1989 Camille Hanks Cosby Deborah Prothrow-Stith, C‘75 * Former Student As of November 2019 Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Max Cleland Herschelle Sullivan Challenor, C’61 Maxine D. -

Introduction Writer Biographies for B&N Classics A. Michael Matin Is a Professor in the English Department of Warren Wilson

Introduction Writer Biographies for B&N Classics A. Michael Matin is a professor in the English Department of Warren Wilson College, where he teaches late-nineteenth-century and twentieth-century British and Anglophone postcolonial literature. His essays have appeared in Studies in the Novel, The Journal of Modern Literature, Scribners’ British Writers, Scribners’ World Poets, and the Norton Critical Edition of Kipling’s Kim. Matin wrote Introductions and Notes for Conrad’s Lord Jim and Heart of Darkness and Selected Short Fiction. Alfred Mac Adam, Professor at Barnard College–Columbia University, teaches Latin American and comparative literature. He is a translator of Latin American fiction and writes extensively on art. He has written an Introductions and Notes for H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine and The Invisible Man and The War of the Worlds, Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’ Les Liasons Dangereuses, and Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey. Amanda Claybaugh is Associate Professor of English and comparative literature at Columbia University. She is currently at work on a project that considers the relation between social reform and the literary marketplace in the nineteenth-century British and American novel. She has written an Introductions and Notes for Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. Amy Billone is Assistant Professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville where her specialty is 19th Century British literature. She is the author of Little Songs: Women, Silence and the Nineteenth-Century Sonnet and has published articles on both children’s literature and poetry in numerous places. She wrote the Introduction and Notes for Peter Pan by J. -

Women's History Is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating in Communities

Women’s History is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating In Communities A How-To Community Handbook Prepared by The President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History “Just think of the ideas, the inventions, the social movements that have so dramatically altered our society. Now, many of those movements and ideas we can trace to our own founding, our founding documents: the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. And we can then follow those ideas as they move toward Seneca Falls, where 150 years ago, women struggled to articulate what their rights should be. From women’s struggle to gain the right to vote to gaining the access that we needed in the halls of academia, to pursuing the jobs and business opportunities we were qualified for, to competing on the field of sports, we have seen many breathtaking changes. Whether we know the names of the women who have done these acts because they stand in history, or we see them in the television or the newspaper coverage, we know that for everyone whose name we know there are countless women who are engaged every day in the ordinary, but remarkable, acts of citizenship.” —- Hillary Rodham Clinton, March 15, 1999 Women’s History is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating In Communities A How-To Community Handbook prepared by the President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History Commission Co-Chairs: Ann Lewis and Beth Newburger Commission Members: Dr. Johnnetta B. Cole, J. Michael Cook, Dr. Barbara Goldsmith, LaDonna Harris, Gloria Johnson, Dr. Elaine Kim, Dr. -

FAULTLINES the K.P.S

FAULTLINES The K.P.S. Gill Journal of Conflict & Resolution Volume 26 FAULTLINES The K.P.S. Gill Journal of Conflict & Resolution Volume 26 edited by AJAI SAHNI Kautilya Books & THE INSTITUTE FOR CONFLICT MANAGEMENT All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. © The Institute for Conflict Management, New Delhi November 2020 ISBN : 978-81-948233-1-5 Price: ` 250 Overseas: US$ 30 Printed by: Kautilya Books 309, Hari Sadan, 20, Ansari Road Daryaganj, New Delhi-110 002 Phone: 011 47534346, +91 99115 54346 Faultlines: the k.p.s. gill journal of conflict & resolution Edited by Ajai Sahni FAULTLINES - THE SERIES FAULTLINES focuses on various sources and aspects of existing and emerging conflict in the Indian subcontinent. Terrorism and low-intensity wars, communal, caste and other sectarian strife, political violence, organised crime, policing, the criminal justice system and human rights constitute the central focus of the Journal. FAULTLINES is published each quarter by the INSTITUTE FOR CONFLICT MANAGEMENT. PUBLISHER & EDITOR Dr. Ajai Sahni ASSISTANT EDITOR Dr. Sanchita Bhattacharya EDITORIAL CONSULTANTS Prof. George Jacob Vijendra Singh Jafa Chandan Mitra The views expressed in FAULTLINES are those of the authors, and not necessarily of the INSTITUTE FOR CONFLICT MANAGEMENT. FAULTLINES seeks to provide a forum for the widest possible spectrum of research and opinion on South Asian conflicts. Contents Foreword i 1. Digitised Hate: Online Radicalisation in Pakistan & Afghanistan: Implications for India 1 ─ Peter Chalk 2. -

Muhammad Speaking of the Messiah: Jesus in the Hadīth Tradition

MUHAMMAD SPEAKING OF THE MESSIAH: JESUS IN THE HADĪTH TRADITION A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Fatih Harpci (May 2013) Examining Committee Members: Prof. Khalid Y. Blankinship, Advisory Chair, Department of Religion Prof. Vasiliki Limberis, Department of Religion Prof. Terry Rey, Department of Religion Prof. Zameer Hasan, External Member, TU Department of Physics © Copyright 2013 by Fatih Harpci All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT Much has been written about Qur’ānic references to Jesus (‘Īsā in Arabic), yet no work has been done on the structure or formal analysis of the numerous references to ‘Īsā in the Hadīth, that is, the collection of writings that report the sayings and actions of the Prophet Muhammad. In effect, non-Muslims and Muslim scholars neglect the full range of Prophet Muhammad’s statements about Jesus that are in the Hadīth. The dissertation’s main thesis is that an examination of the Hadīths’ reports of Muhammad’s words about and attitudes toward ‘Īsā will lead to fuller understandings about Jesus-‘Īsā among Muslims and propose to non-Muslims new insights into Christian tradition about Jesus. In the latter process, non-Muslims will be encouraged to re-examine past hostile views concerning Muhammad and his words about Jesus. A minor thesis is that Western readers in particular, whether or not they are Christians, will be aided to understand Islamic beliefs about ‘Īsā, prophethood, and eschatology more fully. In the course of the dissertation, Hadīth studies will be enhanced by a full presentation of Muhammad’s words about and attitudes toward Jesus-‘Īsā. -

UNIVERSITY of BELGRADE FACULTY of POLITICAL SCIENCE Regional Master's Program in Peace Studies MASTER's THESIS Revisiting T

UNIVERSITY OF BELGRADE FACULTY OF POLITICAL SCIENCE Regional Master’s Program in Peace Studies MASTER’S THESIS Revisiting the Orange Revolution and Euromaidan: Pro-Democracy Civil Disobedience in Ukraine Academic supervisor: Student: Associate Professor Marko Simendić Olga Vasilevich 9/18 Belgrade, 2020 1 Content Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………3 1. Theoretical section……………………………………………………………………………..9 1.1 Civil disobedience…………………………………………………………………………9 1.2 Civil society……………………………………………………………………………... 19 1.3 Nonviolence……………………………………………………………………………... 24 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………… 31 2. Analytical section……………………………………………………………………………..33 2.1 The framework for disobedience………………………………………………….…….. 33 2.2 Orange Revolution………………………………………………………………………. 40 2.3 Euromaidan……………………………………………………………………………… 47 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………… 59 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………… 62 References……………………………………………………………………………………….67 2 INTRODUCTION The Orange Revolution and the Revolution of Dignity have precipitated the ongoing Ukraine crisis. According to the United Nations Rights Office, the latter has claimed the lives of 13,000 people, including those of unarmed civilian population, and entailed 30,000 wounded (Miller 2019). The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees adds to that 1.5 million internally displaced persons (IDPs), 100,000 refugees and asylum-seekers (UNHCR 2014). The armed conflict is of continued relevance to Russia, Europe, as well as the United States. During the first 10 months, -

Alternative Perspectives of African American Culture and Representation in the Works of Ishmael Reed

ALTERNATIVE PERSPECTIVES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN CULTURE AND REPRESENTATION IN THE WORKS OF ISHMAEL REED A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of Zo\% The requirements for IMl The Degree Master of Arts In English: Literature by Jason Andrew Jackl San Francisco, California May 2018 Copyright by Jason Andrew Jackl 2018 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read Alternative Perspectives o f African American Culture and Representation in the Works o f Ishmael Reed by Jason Andrew Jackl, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts in English Literature at San Francisco State University. Geoffrey Grec/C Ph.D. Professor of English Sarita Cannon, Ph.D. Associate Professor of English ALTERNATIVE PERSPECTIVES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN CULTURE AND REPRESENTATION IN THE WORKS OF ISHMAEL REED Jason Andrew JackI San Francisco, California 2018 This thesis demonstrates the ways in which Ishmael Reed proposes incisive countemarratives to the hegemonic master narratives that perpetuate degrading misportrayals of Afro American culture in the historical record and mainstream news and entertainment media of the United States. Many critics and readers have responded reductively to Reed’s work by hastily dismissing his proposals, thereby disallowing thoughtful critical engagement with Reed’s views as put forth in his fiction and non fiction writing. The study that follows asserts that Reed’s corpus deserves more thoughtful critical and public recognition than it has received thus far. To that end, I argue that a critical re-exploration of his fiction and non-fiction writing would yield profound contributions to the ongoing national dialogue on race relations in America. -

Publishing Blackness: Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE publishing blackness publishing blackness Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850 George Hutchinson and John K. Young, editors The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2013 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Publishing blackness : textual constructions of race since 1850 / George Hutchinson and John Young, editiors. pages cm — (Editorial theory and literary criticism) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 472- 11863- 2 (hardback) — ISBN (invalid) 978- 0- 472- 02892- 4 (e- book) 1. American literature— African American authors— History and criticism— Theory, etc. 2. Criticism, Textual. 3. American literature— African American authors— Publishing— History. 4. Literature publishing— Political aspects— United States— History. 5. African Americans— Intellectual life. 6. African Americans in literature. I. Hutchinson, George, 1953– editor of compilation. II. Young, John K. (John Kevin), 1968– editor of compilation PS153.N5P83 2012 810.9'896073— dc23 2012042607 acknowledgments Publishing Blackness has passed through several potential versions before settling in its current form. -

Gwendolyn Brooks 1917–2000

Name _____________________________ Class _________________ Date __________________ The Civil Rights Movement Biography Gwendolyn Brooks 1917–2000 WHY SHE MADE HISTORY Gwendolyn Brooks was an award-winning poet, novelist, and a leader of the Black Arts Movement. She was also the first African American poet to receive a Pulitzer Prize. As you read the biography below, think about the role Gwendolyn Brooks’ writing played in the civil rights movement. Why was her poetry significant? Bettmann/CORBIS © As African Americans worked to bring an end to discrimination, most still lived in poor inner city neighborhoods. The Black Power movement focused on the need for social and economic reforms. A Black Arts Movement also emerged to tell the story of African American life. Poet Gwendolyn Brooks was at the forefront of this movement. Gwendolyn Brooks was born in Topeka, Kansas, in 1917. Two months after her birth, her family moved to Chicago, Illinois, where she would live for the rest of her life. Brooks was a shy child who developed an interest in writing. Her mother encouraged this interest, and teachers helped develop her talent. At an early age, Brooks was published in national magazines and newspapers. After graduation from high school, Brooks entered community college and received an associate’s degree. She worked at many different jobs, from maid to spiritual healer. Later she would write about these experiences. She was also involved in the Youth Council of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and helped found a club for young black artists and writers. Through this club, she met her future husband, poet Henry Blakely. -

The Poetry of Rita Dove

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Winter 1999 Language's "bliss of unfolding" in and through history, autobiography and myth: The poetry of Rita Dove Carol Keyes University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Keyes, Carol, "Language's "bliss of unfolding" in and through history, autobiography and myth: The poetry of Rita Dove" (1999). Doctoral Dissertations. 2107. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2107 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMi films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

歐盟與俄羅斯在烏克蘭危機中之利益競合the Competing Interests Between the EU and Russia in the Crisis of Ukraine

南 華 大 學 國際事務與企業學系歐洲研究碩士班 碩士論文 歐盟與俄羅斯在烏克蘭危機中之利益競合 The Competing Interests between the EU and Russia in the Crisis of Ukraine 研 究 生:張家豪 指導教授:鍾志明 中華民國 106 年 6 月 26 日 南華大學 國際事務與企業學系 歐洲研究碩士班 碩士學位論文 、、、電 歐盟與俄羅斯在烏克蘭危機中之利益競合 The Competing Interests between the EU and Russia in the Crisis of Ukraine 研究生:朱永多 經考試合格特此證明 口試委員: 給州: 指導教授: 主 長 口試日期:中華民國 -0六年六月二十六日 摘 要 1991 年 12 月,前蘇聯加盟共和國的十一位領導人簽署了阿拉木圖宣言;正式 宣告蘇聯中止存在,獨立 國家國協成立。其中,位處波羅的海到黑海中樞位置的 烏克蘭,是個擁有豐富林、礦產業、蘊藏大量煤礦與天然氣資源的國家,而其土 地面積在 東歐大陸上僅次於俄羅斯。1993 年馬斯垂克條約生效,歐洲聯盟正式形 成,為擴大周邊區域的穩定,乃採睦鄰政策,與鄰近國家進行策略結合,整合彼 此 資源、獲取雙邊外交或經濟實需;而位置重要的烏克蘭,自然是歐盟極力爭取 的合作對象。但是,長期作為俄羅斯附庸國的烏克蘭,早已被俄羅斯視為藩屬; 即便獨立國協早已成立,但俄國對烏國的霸權主義及己身國際戰略考量,仍不願 樂見烏克蘭和歐盟、甚至西方國家有密切互動。2013 年烏克蘭爆發政治危機,俄 羅斯以維護安全為藉口派兵進入烏國,歐洲大陸上俄羅斯與歐盟的政經角力,也 再次浮現至檯面上。本文試圖從烏克蘭危機中歐盟與俄羅斯的外交處理方式,探 討烏克蘭在歐洲大陸上的利益競合與未來雙方外交可能面臨的挑戰。 關鍵詞:歐盟、烏克蘭、俄羅斯、睦鄰政策、利益競合 I Summary The dissolution of the Soviet Union and the establishment of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) had been officially announced and realized after the Alma Ata Declaration was signed by 11 leaders of the Soviet Socialist Republics. The Ukraine, the second largest country of Eastern Eurpoe, is located in the pivot of Black Sea and Bsltic Sea. The country is aboundanted in nature resources, such as, woods, mines, coal mines, and gas. The Maastricht Treaty, entered into force since 1993, marked the beginning of formation of the EU. The European Neighbourhood Policy was undertaken in consideration of strategy combination, resource integration, bilateral diplomacy and economic corporation with the neighboring countries. As the result of above, it is reasonable that the Ukraine was certainly the first priority for the EU which they were targeted to buy off for aligment.