OCP-73.1-Annexi-1-Eng.Pdf (6.603Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte D'ivoire, and Togo

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo Public Disclosure Authorized Nga Thi Viet Nguyen and Felipe F. Dizon Public Disclosure Authorized 00000_CVR_English.indd 1 12/6/17 2:29 PM November 2017 The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo Nga Thi Viet Nguyen and Felipe F. Dizon 00000_Geography_Welfare-English.indd 1 11/29/17 3:34 PM Photo Credits Cover page (top): © Georges Tadonki Cover page (center): © Curt Carnemark/World Bank Cover page (bottom): © Curt Carnemark/World Bank Page 1: © Adrian Turner/Flickr Page 7: © Arne Hoel/World Bank Page 15: © Adrian Turner/Flickr Page 32: © Dominic Chavez/World Bank Page 48: © Arne Hoel/World Bank Page 56: © Ami Vitale/World Bank 00000_Geography_Welfare-English.indd 2 12/6/17 3:27 PM Acknowledgments This study was prepared by Nga Thi Viet Nguyen The team greatly benefited from the valuable and Felipe F. Dizon. Additional contributions were support and feedback of Félicien Accrombessy, made by Brian Blankespoor, Michael Norton, and Prosper R. Backiny-Yetna, Roy Katayama, Rose Irvin Rojas. Marina Tolchinsky provided valuable Mungai, and Kané Youssouf. The team also thanks research assistance. Administrative support by Erick Herman Abiassi, Kathleen Beegle, Benjamin Siele Shifferaw Ketema is gratefully acknowledged. Billard, Luc Christiaensen, Quy-Toan Do, Kristen Himelein, Johannes Hoogeveen, Aparajita Goyal, Overall guidance for this report was received from Jacques Morisset, Elisée Ouedraogo, and Ashesh Andrew L. Dabalen. Prasann for their discussion and comments. Joanne Gaskell, Ayah Mahgoub, and Aly Sanoh pro- vided detailed and careful peer review comments. -

Spatio-Temporal Analysis of the Impact of Rainfall Dynamics on the Water Resources of the N'zi Watershed in Côte D'ivoire

Spatio-temporal analysis of the impact of rainfall dynamics on the water resources of the N'zi watershed in Côte d'Ivoire ABSTRACT This study aims to analyze impacts of rainfall dynamic on the water resources (surface water and groundwater) of N'zi watershed in Côte d'Ivoire. It justifies use of monthly average climatological data (rainfall, temperature) and hydrometric data of the watershed. The methodology is to interpolate by kriging rainfall, to highlight relationship between the spatial variability of rainfall and the surface water flow, and to evaluate groundwater recharge of fractured aquifers in the watershed. At the end of the study, it appears that the ten-year average rainfall of the N'zi watershed has decreased significantly. From 1233 mm during the decade 1951-1960, it lowered to 1074 mm during the decade 1991-2000. During the decades 1961-1970, 1971-1980 and 1981-1990, average rainfall is estimated at 1213 mm, 1068 mm and 1050 mm, respectively. From a spatial point of view, decrease in rainfall intensity was strongly felt in the central and northern localities, as in those located in the south of the watershed. Evolution of stream flow and rainfall is similar in the upper and middle N'zi, with maximum flow period in september corresponding mainly to the period of high rainfall. However, two peaks of different amplitude and a slight shift are observed between the peaks of rain and those of flow mainly in low N'zi. Water quantity streamed in the N’zi watershed during the period of 1972 to 2000 is of 40.7 mm. -

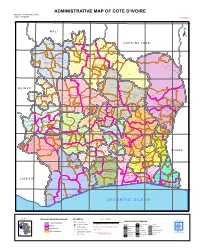

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana -

5 Geology and Groundwater 5 Geology and Groundwater

5 GEOLOGY AND GROUNDWATER 5 GEOLOGY AND GROUNDWATER Table of Contents Page CHAPTER 1 PRESENT CONDITIONS OF TOPOGRAPHY, GEOLOGY AND HYDROGEOLOGY.................................................................... 5 – 1 1.1 Topography............................................................................................................... 5 – 1 1.2 Geology.................................................................................................................... 5 – 2 1.3 Hydrogeology and Groundwater.............................................................................. 5 – 4 CHAPTER 2 GROUNDWATER RESOURCES POTENTIAL ............................... 5 – 13 2.1 Mechanism of Recharge and Flow of Groundwater ................................................ 5 – 13 2.2 Method for Potential Estimate of Groundwater ....................................................... 5 – 13 2.3 Groundwater Potential ............................................................................................. 5 – 16 2.4 Consideration to Select Priority Area for Groundwater Development Project ........ 5 – 18 CHAPTER 3 GROUNDWATER BALANCE STUDY .............................................. 5 – 21 3.1 Mathod of Groundwater Balance Analysis .............................................................. 5 – 21 3.2 Actual Groundwater Balance in 1998 ...................................................................... 5 – 23 3.3 Future Groundwater Balance in 2015 ...................................................................... 5 – 24 CHAPTER -

See Full Prospectus

G20 COMPACT WITHAFRICA CÔTE D’IVOIRE Investment Opportunities G20 Compact with Africa 8°W To 7°W 6°W 5°W 4°W 3°W Bamako To MALI Sikasso CÔTE D'IVOIRE COUNTRY CONTEXT Tengrel BURKINA To Bobo Dioulasso FASO To Kampti Minignan Folon CITIES AND TOWNS 10°N é 10°N Bagoué o g DISTRICT CAPITALS a SAVANES B DENGUÉLÉ To REGION CAPITALS Batie Odienné Boundiali Ferkessedougou NATIONAL CAPITAL Korhogo K RIVERS Kabadougou o —growth m Macroeconomic stability B Poro Tchologo Bouna To o o u é MAIN ROADS Beyla To c Bounkani Bole n RAILROADS a 9°N l 9°N averaging 9% over past five years, low B a m DISTRICT BOUNDARIES a d n ZANZAN S a AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT and stable inflation, contained fiscal a B N GUINEA s Hambol s WOROBA BOUNDARIES z a i n Worodougou d M r a Dabakala Bafing a Bere REGION BOUNDARIES r deficit; sustainable debt Touba a o u VALLEE DU BANDAMA é INTERNATIONAL BOUNDARIES Séguéla Mankono Katiola Bondoukou 8°N 8°N Gontougo To To Tanda Wenchi Nzerekore Biankouma Béoumi Bouaké Tonkpi Lac de Gbêke Business friendly investment Mont Nimba Haut-Sassandra Kossou Sakassou M'Bahiakro (1,752 m) Man Vavoua Zuenoula Iffou MONTAGNES To Danane SASSANDRA- Sunyani Guemon Tiebissou Belier Agnibilékrou climate—sustained progress over the MARAHOUE Bocanda LACS Daoukro Bangolo Bouaflé 7°N 7°N Daloa YAMOUSSOUKRO Marahoue last four years as measured by Doing Duekoue o Abengourou b GHANA o YAMOUSSOUKRO Dimbokro L Sinfra Guiglo Bongouanou Indenie- Toulepleu Toumodi N'Zi Djuablin Business, Global Competitiveness, Oumé Cavally Issia Belier To Gôh CÔTE D'IVOIRE Monrovia -

Emergences Endémiques De Fièvre Jaune Dans La Région

LABORATOIRE D'ENTOMOLOGIE MEDICALE O.R.S.T.O.M. DE L'INSTITUT PASTEUR DE COTE D'IVOIRE O1 BP V-51 Abid.jan O1 O1 BP 490 Abidjan O1 EPERGENCES ENDEMIQUES DE FIEVRE JAUNE DANS LA REGION DE NIAKARAMANDOUGOU REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE. ENQUETE ENTOMO - EPIDEMIOLOGIQUE -. Roger CORDELLIER Bernard BOUCHITE Dr. es-Sciences Technicien supérieur Entomologiste médical ORSTOM d''Entomologie médicale ORSTOM . c I- 1 1. INTRODUCTION . Le décès le 28 novembre 1982 à l'hôpital de Bouaké, après son trans- fert depuis l'hôpital de Niakaramandougou, d'un Instituteur de 24 ans, a pu être rapporté 2 la fièvre jaune par le Dr. M. LHUILLIER (IgM sur un sé- rumpparvenu seulement le 10 décembre à l'Institut Pasteur). Une enquête conjointe IPCI/ORSTOM a été aussitôt décidée. En ce qui concernc le Laboratoire d'Entomologie médicale, elle s'est inscrite dans le cadre de la mission mensuelle effectuée à Dabakala (Surveillance de la fièvre jaune, de la dengue, et:autres arboviroses humaines dans la zone des sava- nes semi-humides), et ses différentes phases réalisées le 14, le 17 et le 19 décembre, B partir de la station de Dabakala, avec le personnel perma- nent du Laboratoire, et le personnel embauché localement sur la station. Les renseignements obtenus, et les observations faites sur place, 1. B l'hôpital de Niakaramandougou, dès le 14 décembre, nous ont conduit à centrer les prospections sur le village de OUREGUEKAHA (nouveau village), situé à environ 25 Km au sud de Niakaramandougou, et sur ARIKOKAHA, village de l'instituteur décédé, 2' 18 Km au nord. -

République De Cote D'ivoire

R é p u b l i q u e d e C o t e d ' I v o i r e REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE C a r t e A d m i n i s t r a t i v e Carte N° ADM0001 AFRIQUE OCHA-CI 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W Débété Papara MALI (! Zanasso Diamankani TENGRELA ! BURKINA FASO San Toumoukoro Koronani Kanakono Ouelli (! Kimbirila-Nord Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko (! Bougou Sokoro Blésségu é Niéllé (! Tiogo Tahara Katogo Solo gnougo Mahalé Diawala Ouara (! Tiorotiérié Kaouara Tienn y Sandrégué Sanan férédougou Sanhala Nambingué Goulia N ! Tindara N " ( Kalo a " 0 0 ' M'Bengué ' Minigan ! 0 ( 0 ° (! ° 0 N'd énou 0 1 Ouangolodougou 1 SAVANES (! Fengolo Tounvré Baya Kouto Poungb é (! Nakélé Gbon Kasséré SamantiguilaKaniasso Mo nogo (! (! Mamo ugoula (! (! Banankoro Katiali Doropo Manadoun Kouroumba (! Landiougou Kolia (! Pitiengomon Tougbo Gogo Nambonkaha Dabadougou-Mafélé Tiasso Kimbirila Sud Dembasso Ngoloblasso Nganon Danoa Samango Fononvogo Varalé DENGUELE Taoura SODEFEL Siansoba Niofouin Madiani (! Téhini Nyamoin (! (! Koni Sinémentiali FERKESSEDOUGOU Angai Gbéléban Dabadougou (! ! Lafokpokaha Ouango-Fitini (! Bodonon Lataha Nangakaha Tiémé Villag e BSokoro 1 (! BOUNDIALI Ponond ougou Siemp urgo Koumbala ! M'b engué-Bougou (! Seydougou ODIENNE Kokoun Séguétiélé Balékaha (! Villag e C ! Nangou kaha Togoniéré Bouko Kounzié Lingoho Koumbolokoro KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Koulokaha Pign on ! Nazinékaha Sikolo Diogo Sirana Ouazomon Noguirdo uo Panzaran i Foro Dokaha Pouan Loyérikaha Karakoro Kagbolodougou Odia Dasso ungboho (! Séguélon Tioroniaradougou -

Côte D'ivoire

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT HOSPITAL INFRASTRUCTURE REHABILITATION AND BASIC HEALTHCARE SUPPORT REPUBLIC OF COTE D’IVOIRE COUNTRY DEPARTMENT OCDW WEST REGION MARCH-APRIL 2000 SCCD : N.G. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS, WEIGHTS AND MEASUREMENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS, LIST OF ANNEXES, SUMMARY, CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS BASIC DATA AND PROJECT MATRIX i to xii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 PROJECT OBJECTIVES AND DESIGN 1 2.1 Project Objectives 1 2.2 Project Description 2 2.3 Project Design 3 3. PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION 3 3.1 Entry into Force and Start-up 3 3.2 Modifications 3 3.3 Implementation Schedule 5 3.4 Quarterly Reports and Accounts Audit 5 3.5 Procurement of Goods and Services 5 3.6 Costs, Sources of Finance and Disbursements 6 4 PROJECT PERFORMANCE AND RESULTS 7 4.1 Operational Performance 7 4.2 Institutional Performance 9 4.3 Performance of Consultants, Contractors and Suppliers 10 5 SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT 11 5.1 Social Impact 11 5.2 Environmental Impact 12 6. SUSTAINABILITY 12 6.1 Infrastructure 12 6.2 Equipment Maintenance 12 6.3 Cost Recovery 12 6.4 Health Staff 12 7. BANK’S AND BORROWER’S PERFORMANCE 13 7.1 Bank’s Performance 13 7.2 Borrower’s Performance 13 8. OVERALL PERFORMANCE AND RATING 13 9. CONCLUSIONS, LESSONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 13 9.1 Conclusions 13 9.2 Lessons 14 9.3 Recommendations 14 Mrs. B. BA (Public Health Expert) and a Consulting Architect prepared this report following their project completion mission in the Republic of Cote d’Ivoire on March-April 2000. -

Projet D'extension Et De Renforcement Du Reseau De Distribution De La Commune De Katiola

REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D’IVOIRE Public Disclosure Authorized Union – Discipline – Travail -------------------------------- MINISTERE DU PETROLE, DE L’ENERGIE ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT DES ENERGIES RENOUVELABLES --------------------------------- PROJET DE TRANSPORT, DE DISTRIBUTION ET D’ACCES À L’ELECTRICITE (PTDAE) --------------------------------- PROJET D’EXTENSION ET DE RENFORCEMENT DU RESEAU DE DISTRIBUTION DE LA COMMUNE DE KATIOLA Public Disclosure Authorized --------------------------------- Public Disclosure Authorized PLAN D’ACTION DE REINSTALLATION (PAR) DES POPULATIONS AFFECTEES PAR LE PROJET -- RAPPORT PROVISOIRE -- Public Disclosure Authorized -- Mai 2018 -- TABLE DES MATIERES LISTE DES TABLEAUX................................................................................................................................................. 3 LISTE DES PLANCHES ................................................................................................................................................. 3 LISTE DES ABREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................................................ 4 DEFINITIONS DES TERMES ....................................................................................................................................... 5 RESUME EXECUTIF ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................... -

Cas Du Département De Katiola, Région Des Savanes De Côte D'ivoire

Répartition spatiale, gestion et exploitation des eaux souterraines : cas du département de Katiola, région des savanes de Côte d’Ivoire Talnan Coulibaly To cite this version: Talnan Coulibaly. Répartition spatiale, gestion et exploitation des eaux souterraines : cas du départe- ment de Katiola, région des savanes de Côte d’Ivoire. Sciences de la Terre. Université Paris-Est, 2009. Français. NNT : 2009PEST1034. tel-00638690 HAL Id: tel-00638690 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00638690 Submitted on 7 Nov 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Université Paris Est Université d ’Abobo-Adjamé France Côte d ’Ivoire Université Paris Est THÈSE pour obtenir le grade de Docteur de l ’Université de Paris Est Spécialité : Sciences de l ’Information Géographique Présentée et soutenue publiquement par Talnan Jean Honoré COULIBALY le 09 juillet 2009 Répartition spatiale, Gestion et Exploitation des eaux souterraines Cas du département de Katiola, région des savanes de Côte d ’Ivoire Jury : Qualité Nom et Prénoms Grade, Organisme d ’appartenance Lieu d ’exercice label Labo, adresse DEROIN Jean-Paul Professeur, EA 4119 G2I Directeurs de Thèse Univ. Paris-Est Marne la Vallée Univ. Paris-Est Marne la Vallée (France) SAVANE Issiaka Professeur, Géosciences & Environnement Univ. -

Final Report: International Election Observation Mission to Côte D'ivoire, 2010 Presidential Elections and 2011 Legislative

International Election Observation Mission to Côte d’Ivoire Final Report 2010 Presidential Elections and 2011 Legislative Elections Waging Peace. Fighting Disease. Building Hope. The Carter Center strives to relieve suffering by advancing peace and health worldwide; it seeks to prevent and resolve conflicts, enhance freedom and democracy, and protect and promote human rights worldwide. International Election Observation Mission to Côte d’Ivoire Final Report 2010 Presidential Elections and 2011 Legislative Elections One Copenhill 453 Freedom Parkway Atlanta, GA 30307 (404) 420-5188 Fax (404) 420-5196 www.cartercenter.org The Carter Center Contents Foreword ..................................1 The Appeals Process ......................63 Executive Summary and Recommendations......3 Election-Related Violence ..................65 The Carter Center in Côte d’Ivoire ............3 Certification of Results . .66 Observation Methodology ....................4 Conclusions and Recommendations Conclusions of the Election Observation Mission ..6 Regarding the 2010 Presidential Election.......67 The Carter Center in Côte d’Ivoire — The Carter Center in Côte d’Ivoire — Presidential Election 2010 ..................16 Legislative Elections 2011 . .72 Political Context...........................18 Political Context...........................74 Framework of the Presidential Election ........21 Hijacking of the Election and the Political- Military Crisis ...........................74 Legal Framework ........................21 Boycott of the Front Populaire -

Urban-Bias and the Roots of Political Instability

Urban-bias and the Roots of Political Instablity: The case for the strategic importance of the rural periphery in sub-Saharan Africa By Beth Sharon Rabinowitz A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Steven K. Vogel, Chair Professor Michael Watts Professor Robert Price Professor Catherine Boone Fall 2013 COPYRIGHT Abstract Urban-bias and the Roots of Political Instablity: The case for the strategic importance of the rural periphery in sub-Saharan Africa By Beth Sharon Rabinowitz Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Steven K. Vogel, Chair Urban-bias and the Roots of Political Instability: the case for the strategic importance of the rural periphery in sub-Saharan Africa seeks to unravel a conundrum in African politics. Since the 1980s, we have witnessed two contradictory trends: on the one hand, coups, which have become rare events world-wide, have continued to proliferate in the region; concurrently, several African countries – such as Ghana, Uganda, Burkina Faso and Benin – have managed to escape from seemingly insurmountable coup-traps. What explains this divergence? To address these contradictory trends, I focus initially on Ghana and Cote d‟Ivoire, neighboring states, with comparable populations, topographies, and economies that have experienced contrasting trajectories. While Ghana suffered five consecutive coups from the 1966 to 1981, Cote d‟Ivoire was an oasis of stability and prosperity. However, by the end of the 20th century, Ghana had emerged as one of the few stable two-party democracies on the continent, as Cote d‟Ivoire slid into civil war.