Secular Humanism and Scientific Creationism: Proposed Standards for Reviewing Curricular Decisions Affecting Students' Relig

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is Atheism, Secularism, Humanism? Academy for Lifelong Learning Fall 2019 Course Leader: David Eller

What is Atheism, Secularism, Humanism? Academy for Lifelong Learning Fall 2019 Course leader: David Eller Course Syllabus Week One: 1. Talking about Theism and Atheism: Getting the Terms Right 2. Arguments for and Against God(s) Week Two: 1. A History of Irreligion and Freethought 2. Varieties of Atheism and Secularism: Non-Belief Across Cultures Week Three: 1. Religion, Non-religion, and Morality: On Being Good without God(s) 2. Explaining Religion Scientifically: Cognitive Evolutionary Theory Week Four: 1. Separation of Church and State in the United States 2. Atheist/Secularist/Humanist Organization and Community Today Suggested Reading List David Eller, Natural Atheism (American Atheist Press, 2004) David Eller, Atheism Advanced (American Atheist Press, 2007) Other noteworthy readings on atheism, secularism, and humanism: George M. Smith Atheism: The Case Against God Richard Dawkins The God Delusion Christopher Hitchens God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything Daniel Dennett Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon Victor Stenger God: The Failed Hypothesis Sam Harris The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Religion Michael Martin Atheism: A Philosophical Justification Kerry Walters Atheism: A Guide for the Perplexed Michel Onfray In Defense of Atheism: The Case against Christianity, Judaism, and Islam John M. Robertson A Short History of Freethought Ancient and Modern William Lane Craig and Walter Sinnott-Armstrong God? A Debate between a Christian and an Atheist Phil Zuckerman and John R. Shook, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Secularism Janet R. Jakobsen and Ann Pellegrini, eds. Secularisms Callum G. Brown The Death of Christian Britain: Understanding Secularisation 1800-2000 Talal Asad Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity Lori G. -

Introduction: the Emerging Alliance of World Religions and Ecology

Emerging Alliance of World Religions and Ecology 1 Mary Evelyn Tucker and John A. Grim Introduction: The Emerging Alliance of World Religions and Ecology HIS ISSUE OF DÆDALUS brings together for the first time diverse perspectives from the world’s religious traditions T regarding attitudes toward nature with reflections from the fields of science, public policy, and ethics. The scholars of religion in this volume identify symbolic, scriptural, and ethical dimensions within particular religions in their relations with the natural world. They examine these dimensions both historically and in response to contemporary environmental problems. Our Dædalus planning conference in October of 1999 fo- cused on climate change as a planetary environmental con- cern.1 As Bill McKibben alerted us more than a decade ago, global warming may well be signaling “the end of nature” as we have come to know it.2 It may prove to be one of our most challenging issues in the century ahead, certainly one that will need the involvement of the world’s religions in addressing its causes and alleviating its symptoms. The State of the World 2000 report cites climate change (along with population) as the critical challenge of the new century. It notes that in solving this problem, “all of society’s institutions—from organized re- ligion to corporations—have a role to play.”3 That religions have a role to play along with other institutions and academic disciplines is also the premise of this issue of Dædalus. The call for the involvement of religion begins with the lead essays by a scientist, a policy expert, and an ethicist. -

Janne Kontala – EMERGING NON-RELIGIOUS WORLDVIEW PROTOTYPES

Janne Kontala | Emerging Non-religious Worldview Prototypes | 2016 Prototypes Worldview Non-religious Janne Kontala | Emerging Janne Kontala Emerging Non-religious Worldview Prototypes A Faith Q-sort-study on Finnish Group-affiliates 9 789517 658386 ISBN 978-951-765-838-6 Åbo Akademis förlag Domkyrkotorget 3, FI-20500 Åbo, Finland Tfn +358 (0)2 215 4793 E-post: forlaget@abo. Försäljning och distribution: Åbo Akademis bibliotek Domkyrkogatan 2-4, FI-20500 Åbo, Finland Tfn +358 (0)2 215 4190 E-post: publikationer@abo. EMERGING NON-RELIGIOUS WORLDVIEW PROTOTYPES Emerging Non-religious Worldview Prototypes A Faith Q-sort-study on Finnish Group-affiliates Janne Kontala Åbo Akademis förlag | Åbo Akademi University Press Åbo, Finland, 2016 CIP Cataloguing in Publication Kontala, Janne. Emerging non-religious worldview prototypes : a faith q-sort-study on Finnish group-affiliates / Janne Kontala. - Åbo : Åbo Akademi University Press, 2016. Diss.: Åbo Akademi University. ISBN 978-951-765-838-6 ISBN 978-951-765-838-6 ISBN 978-951-765-839-3(digital) Painosalama Oy Åbo 2016 ABSTRACT This thesis contributes to the growing body of research on non-religion by examining shared and differentiating patterns in the worldviews of Finnish non-religious group-affiliates. The organisa- tions represented in this study consist of the Union of Freethinkers, Finland’s Humanist Association, Finnish Sceptical Society, Prometheus Camps Support Federation and Capitol Area Atheists. 77 non-randomly selected individuals participated in the study, where their worldviews were analysed with Faith Q-sort, a Q-methodological application designed to assess subjectivity in the worldview domain. FQS was augmented with interviews to gain additional information about the emerging worldview prototypes. -

Schooling and Religion: a Secular Humanist View

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 320 283 EA 021 949 AUTHOR Bauer, Norman J. TITLE Schooling and Religion: A Secular Humanist View. PUB DATE Oct 89 NOTE 23p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Studies Association (Chicago, IL, October 25-26, 1989). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150)-- Reports - Evaluative /Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Educational Philosophy; Elementary Secondary Education; *Humanism; Religion Studies; *Religious Education; State Church Separation ABSTRACT The proper relation between religion and public schooling is addressed in this paper which reviews the secular humanist position and recommends ways to pursue the study of religion in classrooms. This dual purpose is achieved through thefollowing process: (1) reconstruction of an empirical-naturalistic image of reality (Image 1); (2) construction of an image of reflective thought, which is the product of this view of reality (Image 2);and (3) examination of the implications of the twoimages for the philosophy of education, sociopolitical order, and curricular content, organization, and implementation. The secular humanist position is not foreign to the notion of religious ideas and values. Images 1 and 2 stress the contemporary secular humanists' optimistic belief in human nature and scientific reason for the attainmentof human fulfillment. This position is compatible with the stanceheld by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution for theintegration of religious study within public schools. (17 references) (LMI) * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be ma.e * * from the original document. * SCHOOLING AND RELIGION: A SECULAR HUMANIST VIEW Norman J. Bauer, Ed.D. Professor of Education State University of New York Geneseo, New York U S DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of EducahOnal Research and Improvement "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCETHIS URIC IONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTEDBY CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproduced as . -

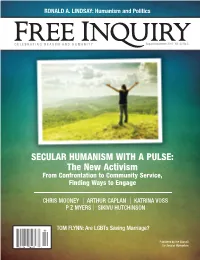

SECULAR HUMANISM with a PULSE: the New Activism from Confrontation to Community Service, Finding Ways to Engage

FI AS C1_Layout 1 6/28/12 10:45 AM Page 1 RONALD A. LINDSAY: Humanism and Politics CELEBRATING REASON AND HUMANITY August/September 2012 Vol. 32 No.5 SECULAR HUMANISM WITH A PULSE: The New Activism From Confrontation to Community Service, Finding Ways to Engage CHRIS MOONEY | ARTHUR CAPLAN | KATRINA VOSS P Z MYERS | SIKIVU HUTCHINSON 09 TOM FLYNN: Are LGBTs Saving Marriage? Published by the Council for Secular Humanism 7725274 74957 FI Aug Sept CUT_FI 6/27/12 4:54 PM Page 3 August/September 2012 Vol. 32 No. 5 CELEBRATING REASON AND HUMANITY 20 Secular Humanism With A Pulse: 30 Grief Beyond Belief The New Activists Rebecca Hensler Introduction Lauren Becker 32 Humanists Care about Humans! Bob Stevenson 22 Sparking a Fire in the Humanist Heart James Croft 34 Not Enough Marthas Reba Boyd Wooden 24 Secular Service in Michigan Mindy Miner 35 The Making of an Angry Atheist Advocate EllenBeth Wachs 25 Campus Service Work Franklin Kramer and Derek Miller 37 Taking Care of Our Own Hemant Mehta 27 Diversity and Secular Activism Alix Jules 39 A Tale of Two Tomes Michael B. Paulkovich 29 Live Well and Help Others Live Well Bill Cooke EDITORIAL 15 Who Cares What Happens 56 The Atheist’s Guide to Reality: 4 Humanism and Politics to Dropouts? Enjoying Life without Illusions Ronald A. Lindsay Nat Hentoff by Alex Rosenberg Reviewed by Jean Kazez LEADING QUESTIONS 16 CFI Gives Women a Voice with 7 The Rise of Islamic Creationism, Part 1 ‘Women in Secularism’ Conference 58 What Jesus Didn’t Say A Conversation with Johan Braeckman Julia Lavarnway by Gerd Lüdemann Reviewed by Robert M. -

Humanism, Atheism, Agnosticism

HANDOUT: HUMANISM FACT SHEET Origin: Dates from Greek and Roman antiquity; then, the European Renaissance; then as a philosophic and theological movement in the U.S. and Europe, mid-1800s and again in 1920s and 1930s, through today. Adherents: Number unknown. Two national organizations are the American Humanist Association and the American Ethical Union. Humanist movements and individuals exist in Buddhism, Christianity, Judaism, and especially Unitarian Universalism. Humanism plays a role in many people's beliefs or spirituality without necessarily being acknowledged. Humanism also plays a role in most faiths without always being named. Influential Figures/Prophets: Protagoras (Greek philosopher, 5th c. BCE, "Man is the measure of all things"), Jane Addams, Charles Darwin, John Dewey, Abraham Maslow, Isaac Asimov, R. Buckminster Fuller (also a Unitarian), Margaret Sanger, Carl Rogers, Bertrand Russell, Andrei Sakharov Texts: No sacred text. Statements of humanist beliefs and intentions are found in three iterations of The Humanist Manifesto: 1933, 1973, and 2003; these are considered explanations of humanist philosophy, not statements of creed. The motto of the American Humanist Association is "Good without a God." To humanists, the broadest range of religious, scientific, moral, political, social texts and creative literature may be valued. Clergy: None. Humanism is not a formally organized religion. Many Unitarian Universalist and other, especially liberal, clergy are Humanists or humanist-influenced. For congregations in the Ethical Culture movement (at www.eswow.org/what-is-ethical- culture), professional Ethical Culture Leaders fill the roles of religious clergy, including meeting the pastoral needs of members, performing ceremonies, and serving as spokespeople for the congregation. -

Sex Education: a Weapon of Mass Destruction? M

The Linacre Quarterly Volume 67 | Number 2 Article 5 May 2000 Sex Education: A Weapon of Mass Destruction? M. C. Asuzu Follow this and additional works at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/lnq Recommended Citation Asuzu, M. C. (2000) "Sex Education: A Weapon of Mass Destruction?," The Linacre Quarterly: Vol. 67: No. 2, Article 5. Available at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/lnq/vol67/iss2/5 Sex Education: A Weapon of Mass Destruction? by Dr. M.e. Asuzu The author is qffiliated with the Department of Preventive & Social Medicine, University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria. He is also Chairman Pro Tem ofthe Nigerian Society for the Study ofBioethics. He is currently on sabbatical in the Fiji Islands. Abstract Education has rightly been understood as fundamentally good for man. In this regard, education is taken in the correct sense both of information and of formation of man, especially of the younger generations. It helps them to achieve the utmost good, individually and societally. Therefore, education concerns the proper nature and good of man. Once these are misunderstood, education will be ill-conceived and ill-delivered. Man's sexuality as the sum total of what makes him male or female in each case is an important component of his nature - physical and metaphysical. It deserves study and education. That aspect of man's sexuality that has to do with physical genital intercourse constitutes a mere 10 to 15% of his sexuality.' It is, however, the most emotive, delicate, and educationally troublesome aspect of man' s sexuality. There has, therefore, been continuing concern that education in this aspect of man requires the most careful and culturally correct environment, tools, and methods. -

Aquinas at the Origins of Secular Humanism? Sources and Innovation in Summa Theologiae I, Question 1, Article 1

N&V_Winter07.qxp 11/13/06 2:32 PM Page 17 Nova et Vetera, English Edition,Vol. 5, No. 1 (2007): 17–40 17 Aquinas at the Origins of Secular Humanism? Sources and Innovation in Summa theologiae I, Question 1, Article 1 WAYNE HANKEY Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia Introduction IN 1968, the influential American neo-Calvinist theologian and cultural historian Francis Schaeffer published a small book, Escape from Reason. He located the origin of this disastrous modern “escape” in the division between nature and grace made by Thomas Aquinas, and in his placing grace above nature. By this account,Thomas draws a horizontal line and places grace above it and nature below.This hierarchical division is what Schaeffer calls “the real birth of the humanistic Renaissance,”and of the autonomy of the human intellect.The reader is told that “from the basis of this autonomous principle, philosophy also became free and was separated from revelation.” Establishing the reality and goodness of the natural was a good thing, but by doing it as he did,“Aquinas had opened the way to an autonomous Humanism, an autonomous philosophy, and once the movement gained momentum, there was soon a flood.”1 This was a bad thing. Schaeffer declares that “[a]ny autonomy is wrong” in respect to Christ and the Scriptures.2 Humans, created in the image of God to whom all belongs, demand by nature a rational whole. Once Aquinas made the division, step by step the autonomous rational ate up what was above the line, rendering it either empty or irrational. -

Humanism in the Americas

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Faculty Contributions to Books Faculty Scholarship 7-2020 Humanism in the Americas Carol W. White Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/fac_books Part of the Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, History of Philosophy Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Latin American History Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation White, Carol W., "Humanism in the Americas" (2020). Faculty Contributions to Books. 211. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/fac_books/211 This Contribution to Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Contributions to Books by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Humanism in the Americas Humanism in the Americas Carol Wayne White The Oxford Handbook of Humanism Edited by Anthony B. Pinn Subject: Religion, Religious Identity, Atheism Online Publication Date: Jul 2020 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190921538.013.11 Abstract and Keywords This chapter provides an overview of select trends, ideas, themes, and figures associated with humanism in the Americas, which comprises a diversified set of peoples, cultural tra ditions, religious orientations, and socio-economic groups. In acknowledging this rich ta pestry of human life, the chapter emphasizes the impressive variety of developments in philosophy, the natural sciences, literature, religion, art, social science, and political thought that have contributed to the development of humanism in the Americas. -

PAUL KURTZ: When Must Humanists Speak Out? PAUL

PAUL KURTZ: When must humanists speak out? f Celebrating Reason and Humanity SUMMER 2003 • VOL. 23 No. 3 Introductory Price $5.95 U.S. / $6.95 Can. 32> 7725274 74957 Published by The Council for Secular Humanism THE AFFIRMATIONS OF HUMANISM: A STATEMENT OF PRINCIPLES* We are committed to the application of reason and science to the understanding of the universe and to the solving of human problems. We deplore efforts to denigrate human intelligence, to seek to explain the world in supernatural terms, and to look outside nature for salvation. We believe that scientific discovery and technology can contribute to the betterment of human life. We believe in an open and pluralistic society and that democracy is the best guarantee of protecting human rights from authoritarian elites and repressive majorities. We are committed to the principle of the separation of church and state. We cultivate the arts of negotiation and compromise as a means of resolving differences and achieving mutual understanding. We are concerned with securing justice and fairness in society and with eliminating discrimination and intolerance. We believe in supporting the disadvantaged and the handicapped so that they will be able to help themselves. We attempt to transcend divisive parochial loyalties based on race, religion, gender, nationality, creed, class, sexual orientation, or ethnicity, and strive to work together for the common good of humanity. We want to protect and enhance the earth, to preserve it for future generations, and to avoid inflicting needless suffering on other species. We believe in enjoying life here and now and in developing our creative talents to their fullest. -

Religious Skepticism, Atheism, Humanism, Naturalism, Secularism, Rationalism, Irreligion, Agnosticism, and Related Perspectives)

Unbelief (Religious Skepticism, Atheism, Humanism, Naturalism, Secularism, Rationalism, Irreligion, Agnosticism, and Related Perspectives) A Historical Bibliography Compiled by J. Gordon Melton ~ San Diego ~ San Diego State University ~ 2011 This bibliography presents primary and secondary sources in the history of unbelief in Western Europe and the United States, from the Enlightenment to the present. It is a living document which will grow and develop as more sources are located. If you see errors, or notice that important items are missing, please notify the author, Dr. J. Gordon Melton at [email protected]. Please credit San Diego State University, Department of Religious Studies in publications. Copyright San Diego State University. ****************************************************************************** Table of Contents Introduction General Sources European Beginnings A. The Sixteenth-Century Challenges to Trinitarianism a. Michael Servetus b. Socinianism and the Polish Brethren B. The Unitarian Tradition a. Ferenc (Francis) David C. The Enlightenment and Rise of Deism in Modern Europe France A. French Enlightenment a. Pierre Bayle (1647-1706) b. Jean Meslier (1664-1729) c. Paul-Henri Thiry, Baron d'Holbach (1723-1789) d. Voltaire (Francois-Marie d'Arouet) (1694-1778) e. Jacques-André Naigeon (1738-1810) f. Denis Diderot (1713-1784) g. Marquis de Montesquieu (1689-1755) h. Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) B. France and Unbelief in the Nineteenth Century a. August Comte (1798-1857) and the Religion of Positivism C. France and Unbelief in the Twentieth Century a. French Existentialism b. Albert Camus (1913 -1960) c. Franz Kafka (1883-1924) United Kingdom A. Deist Beginnings, Flowering, and Beyond a. Edward Herbert, Baron of Cherbury (1583-1648) b. -

Christianity, Secular Humanism, and the Monomyth in Doctor Who

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Liberty University Digital Commons Hardy 1 Mad Hero in a Box: Christianity, Secular Humanism, and the Monomyth in Doctor Who A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences In Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in English By Sabrina N. Hardy 3 April 2015 Hardy 2 Liberty University College of Arts and Sciences Master of Arts in English ________________________________________________________________________ Carl Curtis, Ph.D. Date Thesis Chair ________________________________________________________________________ Mark Harris, Ph.D. Date Committee Member ________________________________________________________________________ Brian Melton, Ph.D. Date Committee Member Hardy 3 Abstract Doctor Who is a long-running, incredibly popular work of television science-fiction, with a devoted fanbase across the Western world. Like all science fiction, it deals with the weighty questions posed by the culture around it, particularly in regards to ethics, politics, faith/belief, and the idea of the soul. These concepts are dealt with through the lens of the Secular Humanist ideology held by the showrunners and by many of the people who watch the show; however, in many areas, elements of the Christian worldview seep through. The conflict between these two worldviews has serious ramifications for the show itself, as it prevents the titular main character from being able to be a traditional, identifiable hero and pushes him ever close to the realm of the anti-hero. This thesis uses Joseph Campbell’s idea of the monomyth, or universal hero’s journey, to provide a framework in which to explore how Christian precepts in the show aid the Doctor in his heroic journey; how Secular Humanist ideologies draw him away from that path; and finally, how the resulting contradictions create an anti-hero who no longer represents the heroic ideal he is supposed to uphold.