Secular Humanism Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HUMANISM Religious Practices

HUMANISM Religious Practices . Required Daily Observances . Required Weekly Observances . Required Occasional Observances/Holy Days Religious Items . Personal Religious Items . Congregate Religious Items . Searches Requirements for Membership . Requirements (Includes Rites of Conversion) . Total Membership Medical Prohibitions Dietary Standards Burial Rituals . Death . Autopsies . Mourning Practices Sacred Writings Organizational Structure . Headquarters Location . Contact Office/Person History Theology 1 Religious Practices Required Daily Observance No required daily observances. Required Weekly Observance No required weekly observances, but many Humanists find fulfillment in congregating with other Humanists on a weekly basis (especially those who characterize themselves as Religious Humanists) or other regular basis for social and intellectual engagement, discussions, book talks, lectures, and similar activities. Required Occasional Observances No required occasional observances, but some Humanists (especially those who characterize themselves as Religious Humanists) celebrate life-cycle events with baby naming, coming of age, and marriage ceremonies as well as memorial services. Even though there are no required observances, there are several days throughout the calendar year that many Humanists consider holidays. They include (but are not limited to) the following: February 12. Darwin Day: This marks the birthday of Charles Darwin, whose research and findings in the field of biology, particularly his theory of evolution by natural selection, represent a breakthrough in human knowledge that Humanists celebrate. First Thursday in May. National Day of Reason: This day acknowledges the importance of reason, as opposed to blind faith, as the best method for determining valid conclusions. June 21 - Summer Solstice. This day is also known as World Humanist Day and is a celebration of the longest day of the year. -

Vol 38 No 2 Schafer Korb Gibbons.Pdf

Not Your Father’s Humanism by David Schafer, Katy Korb and Kendyl Gibbons The 2004 UUA General Assembly in Fort Worth, Texas, featured a panel presentation by the three HUUmanists named above. They showcased the idea to fellow UUs that the humanism espoused and practiced in our ranks is very different from that of the Manifesto generation, and indeed from the UU humanists of the 1960s and 70s. David Schafer You’ve undoubtedly heard the cliché that every movement carries within itself the seeds of its own destruction. This seems to me just a dramatic way of saying “nothing’s perfect.” But if a movement is imperfect, what, if anything, can be done to correct its imperfections? The 20th century Viennese philosopher, Otto Neurath, may have given us a clue when he likened progress in his own field to “rebuilding a leaky boat at sea.” Nature, as always, provides the answer to this dilemma: that answer is evolution. If you attended the Humanist workshop at the General Assembly in Quebec City a few years ago, you may have heard me say that if, as it’s often alleged, the value of real estate “depends on three factors—location, location, and location”—in nature survival of individuals, groups, and (I would add) organizations depends on three factors— adaptation, adaptation, and adaptation. Adaptation is the key to evolution, and evolutionary change is a central theme in Humanism, and always has been. Humanism lives in the real world. Humanism is at home in the real world. And the real world is a moving target. -

What Is Atheism, Secularism, Humanism? Academy for Lifelong Learning Fall 2019 Course Leader: David Eller

What is Atheism, Secularism, Humanism? Academy for Lifelong Learning Fall 2019 Course leader: David Eller Course Syllabus Week One: 1. Talking about Theism and Atheism: Getting the Terms Right 2. Arguments for and Against God(s) Week Two: 1. A History of Irreligion and Freethought 2. Varieties of Atheism and Secularism: Non-Belief Across Cultures Week Three: 1. Religion, Non-religion, and Morality: On Being Good without God(s) 2. Explaining Religion Scientifically: Cognitive Evolutionary Theory Week Four: 1. Separation of Church and State in the United States 2. Atheist/Secularist/Humanist Organization and Community Today Suggested Reading List David Eller, Natural Atheism (American Atheist Press, 2004) David Eller, Atheism Advanced (American Atheist Press, 2007) Other noteworthy readings on atheism, secularism, and humanism: George M. Smith Atheism: The Case Against God Richard Dawkins The God Delusion Christopher Hitchens God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything Daniel Dennett Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon Victor Stenger God: The Failed Hypothesis Sam Harris The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Religion Michael Martin Atheism: A Philosophical Justification Kerry Walters Atheism: A Guide for the Perplexed Michel Onfray In Defense of Atheism: The Case against Christianity, Judaism, and Islam John M. Robertson A Short History of Freethought Ancient and Modern William Lane Craig and Walter Sinnott-Armstrong God? A Debate between a Christian and an Atheist Phil Zuckerman and John R. Shook, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Secularism Janet R. Jakobsen and Ann Pellegrini, eds. Secularisms Callum G. Brown The Death of Christian Britain: Understanding Secularisation 1800-2000 Talal Asad Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity Lori G. -

The Goals of Humanism1

SOUND THE ALARM: THE GOALS OF HUMANISM1 The watchman on the wall of an ancient city had to be alert for signs of danger. His responsibility was to inform others of what he saw. Should he detect a foreign army about to attack, he needed to sound an alarm. In our own American history, we remember the midnight ride of Paul Revere—from Charleston to Medford, and on to Concord and Lexington. So through the night rode Paul Revere And so through the night went his cry of alarm To every Middlesex village and farm.2 Likewise, we must sound an alarm regarding humanism and the dangers it presents to Christians. I wish it were possible for us to shout, as did those watchmen on ancient walls, “The enemy is coming!” But that’s not the message about humanism which we must convey. That message would imply that we are here, and that humanism is off over yonder somewhere. Our message—one which leaves us with a sinking feeling—is more comparable to the announcement that “we’ve got termites in our woodwork!” Humanism is not coming. It’s already here! It has already done much damage. It has already eaten far into the structures of our society. It kills unborn babies. It hurts youth with drugs. It dirties minds with profanity. It turns children against their parents. It robs families of their wealth. It severely damages and often destroys Christian families. If left alone, humanism will eat its way through the country until eventually it has destroyed all Christian homes and churches. -

Introduction: the Emerging Alliance of World Religions and Ecology

Emerging Alliance of World Religions and Ecology 1 Mary Evelyn Tucker and John A. Grim Introduction: The Emerging Alliance of World Religions and Ecology HIS ISSUE OF DÆDALUS brings together for the first time diverse perspectives from the world’s religious traditions T regarding attitudes toward nature with reflections from the fields of science, public policy, and ethics. The scholars of religion in this volume identify symbolic, scriptural, and ethical dimensions within particular religions in their relations with the natural world. They examine these dimensions both historically and in response to contemporary environmental problems. Our Dædalus planning conference in October of 1999 fo- cused on climate change as a planetary environmental con- cern.1 As Bill McKibben alerted us more than a decade ago, global warming may well be signaling “the end of nature” as we have come to know it.2 It may prove to be one of our most challenging issues in the century ahead, certainly one that will need the involvement of the world’s religions in addressing its causes and alleviating its symptoms. The State of the World 2000 report cites climate change (along with population) as the critical challenge of the new century. It notes that in solving this problem, “all of society’s institutions—from organized re- ligion to corporations—have a role to play.”3 That religions have a role to play along with other institutions and academic disciplines is also the premise of this issue of Dædalus. The call for the involvement of religion begins with the lead essays by a scientist, a policy expert, and an ethicist. -

Janne Kontala – EMERGING NON-RELIGIOUS WORLDVIEW PROTOTYPES

Janne Kontala | Emerging Non-religious Worldview Prototypes | 2016 Prototypes Worldview Non-religious Janne Kontala | Emerging Janne Kontala Emerging Non-religious Worldview Prototypes A Faith Q-sort-study on Finnish Group-affiliates 9 789517 658386 ISBN 978-951-765-838-6 Åbo Akademis förlag Domkyrkotorget 3, FI-20500 Åbo, Finland Tfn +358 (0)2 215 4793 E-post: forlaget@abo. Försäljning och distribution: Åbo Akademis bibliotek Domkyrkogatan 2-4, FI-20500 Åbo, Finland Tfn +358 (0)2 215 4190 E-post: publikationer@abo. EMERGING NON-RELIGIOUS WORLDVIEW PROTOTYPES Emerging Non-religious Worldview Prototypes A Faith Q-sort-study on Finnish Group-affiliates Janne Kontala Åbo Akademis förlag | Åbo Akademi University Press Åbo, Finland, 2016 CIP Cataloguing in Publication Kontala, Janne. Emerging non-religious worldview prototypes : a faith q-sort-study on Finnish group-affiliates / Janne Kontala. - Åbo : Åbo Akademi University Press, 2016. Diss.: Åbo Akademi University. ISBN 978-951-765-838-6 ISBN 978-951-765-838-6 ISBN 978-951-765-839-3(digital) Painosalama Oy Åbo 2016 ABSTRACT This thesis contributes to the growing body of research on non-religion by examining shared and differentiating patterns in the worldviews of Finnish non-religious group-affiliates. The organisa- tions represented in this study consist of the Union of Freethinkers, Finland’s Humanist Association, Finnish Sceptical Society, Prometheus Camps Support Federation and Capitol Area Atheists. 77 non-randomly selected individuals participated in the study, where their worldviews were analysed with Faith Q-sort, a Q-methodological application designed to assess subjectivity in the worldview domain. FQS was augmented with interviews to gain additional information about the emerging worldview prototypes. -

PAGANISM a Brief Overview of the History of Paganism the Term Pagan Comes from the Latin Paganus Which Refers to Those Who Lived in the Country

PAGANISM A brief overview of the history of Paganism The term Pagan comes from the Latin paganus which refers to those who lived in the country. When Christianity began to grow in the Roman Empire, it did so at first primarily in the cities. The people who lived in the country and who continued to believe in “the old ways” came to be known as pagans. Pagans have been broadly defined as anyone involved in any religious act, practice, or ceremony which is not Christian. Jews and Muslims also use the term to refer to anyone outside their religion. Some define paganism as a religion outside of Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism, Islam, and Buddhism; others simply define it as being without a religion. Paganism, however, often is not identified as a traditional religion per se because it does not have any official doctrine; however, it has some common characteristics within its variety of traditions. One of the common beliefs is the divine presence in nature and the reverence for the natural order in life. In the strictest sense, paganism refers to the authentic religions of ancient Greece and Rome and the surrounding areas. The pagans usually had a polytheistic belief in many gods but only one, which represents the chief god and supreme godhead, is chosen to worship. The Renaissance of the 1500s reintroduced the ancient Greek concepts of Paganism. Pagan symbols and traditions entered European art, music, literature, and ethics. The Reformation of the 1600s, however, put a temporary halt to Pagan thinking. Greek and Roman classics, with their focus on Paganism, were accepted again during the Enlightenment of the 1700s. -

Schooling and Religion: a Secular Humanist View

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 320 283 EA 021 949 AUTHOR Bauer, Norman J. TITLE Schooling and Religion: A Secular Humanist View. PUB DATE Oct 89 NOTE 23p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Studies Association (Chicago, IL, October 25-26, 1989). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150)-- Reports - Evaluative /Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Educational Philosophy; Elementary Secondary Education; *Humanism; Religion Studies; *Religious Education; State Church Separation ABSTRACT The proper relation between religion and public schooling is addressed in this paper which reviews the secular humanist position and recommends ways to pursue the study of religion in classrooms. This dual purpose is achieved through thefollowing process: (1) reconstruction of an empirical-naturalistic image of reality (Image 1); (2) construction of an image of reflective thought, which is the product of this view of reality (Image 2);and (3) examination of the implications of the twoimages for the philosophy of education, sociopolitical order, and curricular content, organization, and implementation. The secular humanist position is not foreign to the notion of religious ideas and values. Images 1 and 2 stress the contemporary secular humanists' optimistic belief in human nature and scientific reason for the attainmentof human fulfillment. This position is compatible with the stanceheld by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution for theintegration of religious study within public schools. (17 references) (LMI) * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be ma.e * * from the original document. * SCHOOLING AND RELIGION: A SECULAR HUMANIST VIEW Norman J. Bauer, Ed.D. Professor of Education State University of New York Geneseo, New York U S DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of EducahOnal Research and Improvement "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCETHIS URIC IONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTEDBY CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproduced as . -

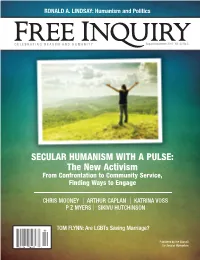

SECULAR HUMANISM with a PULSE: the New Activism from Confrontation to Community Service, Finding Ways to Engage

FI AS C1_Layout 1 6/28/12 10:45 AM Page 1 RONALD A. LINDSAY: Humanism and Politics CELEBRATING REASON AND HUMANITY August/September 2012 Vol. 32 No.5 SECULAR HUMANISM WITH A PULSE: The New Activism From Confrontation to Community Service, Finding Ways to Engage CHRIS MOONEY | ARTHUR CAPLAN | KATRINA VOSS P Z MYERS | SIKIVU HUTCHINSON 09 TOM FLYNN: Are LGBTs Saving Marriage? Published by the Council for Secular Humanism 7725274 74957 FI Aug Sept CUT_FI 6/27/12 4:54 PM Page 3 August/September 2012 Vol. 32 No. 5 CELEBRATING REASON AND HUMANITY 20 Secular Humanism With A Pulse: 30 Grief Beyond Belief The New Activists Rebecca Hensler Introduction Lauren Becker 32 Humanists Care about Humans! Bob Stevenson 22 Sparking a Fire in the Humanist Heart James Croft 34 Not Enough Marthas Reba Boyd Wooden 24 Secular Service in Michigan Mindy Miner 35 The Making of an Angry Atheist Advocate EllenBeth Wachs 25 Campus Service Work Franklin Kramer and Derek Miller 37 Taking Care of Our Own Hemant Mehta 27 Diversity and Secular Activism Alix Jules 39 A Tale of Two Tomes Michael B. Paulkovich 29 Live Well and Help Others Live Well Bill Cooke EDITORIAL 15 Who Cares What Happens 56 The Atheist’s Guide to Reality: 4 Humanism and Politics to Dropouts? Enjoying Life without Illusions Ronald A. Lindsay Nat Hentoff by Alex Rosenberg Reviewed by Jean Kazez LEADING QUESTIONS 16 CFI Gives Women a Voice with 7 The Rise of Islamic Creationism, Part 1 ‘Women in Secularism’ Conference 58 What Jesus Didn’t Say A Conversation with Johan Braeckman Julia Lavarnway by Gerd Lüdemann Reviewed by Robert M. -

The Making of Manifesto I Shows, Six Years Later an Attempt at Improving the Document Failed for Want of Support

fied by a belief in their transcendent real battle of religion is not that of conflict References nature, in their absoluteness independent with other religions, but of a religious fol- Bouquet, A. C. 1948. Hinduism. London: Hutchin- of human initiative. Yet, because they are lower within himself, in order to try to son. not transcendental, not of divine origin, preserve the true values of his faith. Findlay, J. N. 1963. Language, Mind, and Value. they can be easily set aside by the pres- London: Allen & Unwin. This article is excerpted from Raymond Firth's forth- Richardson, Alan and Bowden, John (eds.) 1963. A sure of individual or group human inter- coming book Religion: A Humanist Interpretation New Dictionary of Christian Theology, London: ests. As many wise men have seen, the (Routledge 1996). SCM Press. with its falseness. As Wilson's book The Making of Manifesto I shows, six years later an attempt at improving the document failed for want of support. The last chapter of the book briefly mentions Humanist Manifesto II (1972) Herbert A. Tonne and indicates that Edmund Wilson was recognized as editor emeritus but fails to hen Edmund Wilson was eased out state that Manifesto II was in large mea- Wof his job as Executive Director of "Stripped of embroidery and sure written .by Paul Kurtz. There has the American Humanist Association, he padding, Manifesto l is a state- been some discussion of the development soon thereafter (1967) founded the ment of nonbelief in traditional of a Humanist Manifesto III. Since 1933 Fellowship of Religious Humanism. religion that, nevertheless, does and especially since 1972 there has been During the period in which I was treasurer not wish to offend traditionalists:' so much diversification in opinion among of the Fellowship, Corliss Lamont gave humanists that it would be impossible to the organization $10,000 a year, of which Evolutionary Humanism would become do justice to all versions. -

Secular Humanism and Scientific Creationism: Proposed Standards for Reviewing Curricular Decisions Affecting Students' Relig

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Faculty Scholarship Articles & Chapters 1986 Secular Humanism and Scientific rC eationism: Proposed Standards for Reviewing Curricular Decisions Affecting Students' Religious Freedom Symposium: The eT nsion between the Free Exercise Clause and the Establishment Clause and the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment Nadine Strossen New York Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters Recommended Citation 47 Ohio St. L.J. 333 (1986) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. "Secular Humanism" and "Scientific Creationism": Proposed Standards for Reviewing Curricular Decisions Affecting Students' Religious Freedom NADiNE STROSSEN* INTRODUCrION Many of the latest skirmishes in the ongoing struggle to maintain public schools' neutrality concerning religion have involved "secular humanism" and "scientific creationism" or "creation science." 1 Some parents, children, and religious leaders assert that public school curricula promote the "religion" of secular humanism and inhibit their own religions, 2 thereby violating the establishment clause and the free exercise clause.3 These parents, students, and religious leaders view the Darwinian theory of evolution as a primary tenet of secular humanism. Consequently, they contend that their religious freedom is violated when a public school's instruction concerning the origins of the universe and mankind considers only the evolutionary theory. To counter this perceived violation, they maintain that any public school discussion of origins must present scientific evidence supporting the theory of 4 creation, as well as the theory of evolution. -

Humanism, Atheism, Agnosticism

HANDOUT: HUMANISM FACT SHEET Origin: Dates from Greek and Roman antiquity; then, the European Renaissance; then as a philosophic and theological movement in the U.S. and Europe, mid-1800s and again in 1920s and 1930s, through today. Adherents: Number unknown. Two national organizations are the American Humanist Association and the American Ethical Union. Humanist movements and individuals exist in Buddhism, Christianity, Judaism, and especially Unitarian Universalism. Humanism plays a role in many people's beliefs or spirituality without necessarily being acknowledged. Humanism also plays a role in most faiths without always being named. Influential Figures/Prophets: Protagoras (Greek philosopher, 5th c. BCE, "Man is the measure of all things"), Jane Addams, Charles Darwin, John Dewey, Abraham Maslow, Isaac Asimov, R. Buckminster Fuller (also a Unitarian), Margaret Sanger, Carl Rogers, Bertrand Russell, Andrei Sakharov Texts: No sacred text. Statements of humanist beliefs and intentions are found in three iterations of The Humanist Manifesto: 1933, 1973, and 2003; these are considered explanations of humanist philosophy, not statements of creed. The motto of the American Humanist Association is "Good without a God." To humanists, the broadest range of religious, scientific, moral, political, social texts and creative literature may be valued. Clergy: None. Humanism is not a formally organized religion. Many Unitarian Universalist and other, especially liberal, clergy are Humanists or humanist-influenced. For congregations in the Ethical Culture movement (at www.eswow.org/what-is-ethical- culture), professional Ethical Culture Leaders fill the roles of religious clergy, including meeting the pastoral needs of members, performing ceremonies, and serving as spokespeople for the congregation.