Christianity, Secular Humanism, and the Monomyth in Doctor Who

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

The Wall of Lies

The Wall of Lies Number 142 Newsletter established 1991, club formed June first 1980 The newsletter of the South Australian Doctor Who Fan Club Inc., also known as SFSA MFinal STATE Adelaide, May--June 2013 WEATHER: Cold, wet, some oxygen Free Austerity Budget for Rich, Evil by staff writers Australian budget mildly inconvenient for terrible people. The Tuesday 14 May 2013 federal Australian budget has upset miners, their friends and well wishers around the world. Miners have claimed $11 billion in tax breaks, largely for purchasing smaller companies who have spent on exploration. Across Europe, countries suffering severe austerity cuts have looked beyond their own suffering to reach out to the maggots unable to use this scam any more. In Cyprus a protest march of malnourished children wound its way through Nicosia, Greeks self immolated and an ensemble of Latvians showed solidarity by playing The Smallest Violins In The World. “Come on, what else are you going to do with the rocks? Leave them in the ground until someone who’s O ut willing to pay to dig them up comes along?” asked a t N An untended consequence of No bloated mining executive. ow the severe budget involves pets ! unable to afford faces. But then apparently choked on their own bile. BBC/ABC Divorce, Dr Who Love Child by staff writers BBC cancels ABC contract, Doctor Who excluded. News broke on 17 April 2013 via a joint BBC/Foxtel press release that BBC Worldwide (formerly BBC Enterprises) had decided to Chameleon Factor # 80 finish its output deal with the ABC when the current three year O contract expires mid-2014. -

Helena Mace Song List 2010S Adam Lambert – Mad World Adele – Don't You Remember Adele – Hiding My Heart Away Adele

Helena Mace Song List 2010s Adam Lambert – Mad World Adele – Don’t You Remember Adele – Hiding My Heart Away Adele – One And Only Adele – Set Fire To The Rain Adele- Skyfall Adele – Someone Like You Birdy – Skinny Love Bradley Cooper and Lady Gaga - Shallow Bruno Mars – Marry You Bruno Mars – Just The Way You Are Caro Emerald – That Man Charlene Soraia – Wherever You Will Go Christina Perri – Jar Of Hearts David Guetta – Titanium - acoustic version The Chicks – Travelling Soldier Emeli Sande – Next To Me Emeli Sande – Read All About It Part 3 Ella Henderson – Ghost Ella Henderson - Yours Gabrielle Aplin – The Power Of Love Idina Menzel - Let It Go Imelda May – Big Bad Handsome Man Imelda May – Tainted Love James Blunt – Goodbye My Lover John Legend – All Of Me Katy Perry – Firework Lady Gaga – Born This Way – acoustic version Lady Gaga – Edge of Glory – acoustic version Lily Allen – Somewhere Only We Know Paloma Faith – Never Tear Us Apart Paloma Faith – Upside Down Pink - Try Rihanna – Only Girl In The World Sam Smith – Stay With Me Sia – California Dreamin’ (Mamas and Papas) 2000s Alicia Keys – Empire State Of Mind Alexandra Burke - Hallelujah Adele – Make You Feel My Love Amy Winehouse – Love Is A Losing Game Amy Winehouse – Valerie Amy Winehouse – Will You Love Me Tomorrow Amy Winehouse – Back To Black Amy Winehouse – You Know I’m No Good Coldplay – Fix You Coldplay - Yellow Daughtry/Gaga – Poker Face Diana Krall – Just The Way You Are Diana Krall – Fly Me To The Moon Diana Krall – Cry Me A River DJ Sammy – Heaven – slow version Duffy -

What Is Atheism, Secularism, Humanism? Academy for Lifelong Learning Fall 2019 Course Leader: David Eller

What is Atheism, Secularism, Humanism? Academy for Lifelong Learning Fall 2019 Course leader: David Eller Course Syllabus Week One: 1. Talking about Theism and Atheism: Getting the Terms Right 2. Arguments for and Against God(s) Week Two: 1. A History of Irreligion and Freethought 2. Varieties of Atheism and Secularism: Non-Belief Across Cultures Week Three: 1. Religion, Non-religion, and Morality: On Being Good without God(s) 2. Explaining Religion Scientifically: Cognitive Evolutionary Theory Week Four: 1. Separation of Church and State in the United States 2. Atheist/Secularist/Humanist Organization and Community Today Suggested Reading List David Eller, Natural Atheism (American Atheist Press, 2004) David Eller, Atheism Advanced (American Atheist Press, 2007) Other noteworthy readings on atheism, secularism, and humanism: George M. Smith Atheism: The Case Against God Richard Dawkins The God Delusion Christopher Hitchens God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything Daniel Dennett Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon Victor Stenger God: The Failed Hypothesis Sam Harris The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Religion Michael Martin Atheism: A Philosophical Justification Kerry Walters Atheism: A Guide for the Perplexed Michel Onfray In Defense of Atheism: The Case against Christianity, Judaism, and Islam John M. Robertson A Short History of Freethought Ancient and Modern William Lane Craig and Walter Sinnott-Armstrong God? A Debate between a Christian and an Atheist Phil Zuckerman and John R. Shook, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Secularism Janet R. Jakobsen and Ann Pellegrini, eds. Secularisms Callum G. Brown The Death of Christian Britain: Understanding Secularisation 1800-2000 Talal Asad Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity Lori G. -

Introduction: the Emerging Alliance of World Religions and Ecology

Emerging Alliance of World Religions and Ecology 1 Mary Evelyn Tucker and John A. Grim Introduction: The Emerging Alliance of World Religions and Ecology HIS ISSUE OF DÆDALUS brings together for the first time diverse perspectives from the world’s religious traditions T regarding attitudes toward nature with reflections from the fields of science, public policy, and ethics. The scholars of religion in this volume identify symbolic, scriptural, and ethical dimensions within particular religions in their relations with the natural world. They examine these dimensions both historically and in response to contemporary environmental problems. Our Dædalus planning conference in October of 1999 fo- cused on climate change as a planetary environmental con- cern.1 As Bill McKibben alerted us more than a decade ago, global warming may well be signaling “the end of nature” as we have come to know it.2 It may prove to be one of our most challenging issues in the century ahead, certainly one that will need the involvement of the world’s religions in addressing its causes and alleviating its symptoms. The State of the World 2000 report cites climate change (along with population) as the critical challenge of the new century. It notes that in solving this problem, “all of society’s institutions—from organized re- ligion to corporations—have a role to play.”3 That religions have a role to play along with other institutions and academic disciplines is also the premise of this issue of Dædalus. The call for the involvement of religion begins with the lead essays by a scientist, a policy expert, and an ethicist. -

HILLS to HAWKESBURY CLASSIFIEDS Support Your Local Community’S Businesses

September 18 - October 4 Volume 32 - Issue 19 THE HAWKESBURY RIVER BRIDGE is part of the Sydney Trains rail network. The bridge is a multi-span underbridge located at 58.46 km on the Main North Line. It was constructed around 1945, adjacent to the original 1889 structure which it replaced. The main river spans consist of a variety of steel through trusses with concrete land spans. The substructure consists of two abutments on shallow foundations and nine piers supported by caissons bedded into the river soil or rock. Underwater inspections are undertaken every six years as part of ST’s bridge management program. The most recent underwater inspection was in May MARK VINT Motorcycles 2013. Results identified significant deterioration Suitable for Wrecking on the top of the downstream reinforced concrete 9651 2182 cylinder of pier no 2, including concrete section loss Any Condition 270 New Line Road of up to 750mm in the zone directly underneath the Dural NSW 2158 Dirt, MX, Farm, 4x4 marrying slab. [email protected] ABN: 84 451 806 754 Wreckers Opening Soon Sydney Trains is reviewing its options to fix these WWW.DURALAUTO.COM 0428 266 040 issues. “Can you keep my dog from Gentle Dental Care For Your Whole Family. Sandstone getting out?” Two for the price of One Sales Check-up and Cleans Buy Direct From the Quarry Ph 9680 2400 When you mention this ad. Come & meet 432 Old Northern Rd vid 9652 1783 Call for a Booking Now! Dr Da Glenhaven Ager Handsplit Opposite Flower Power It’s time for your Spring Clean ! Random Flagging $55m2 113 Smallwood Rd Glenorie C & M AUTO’S Free ONE STOP SHOP battery Let us turn your tired car into a backup when you mention finely tuned “Road Runner” “We Certainly Can!” this ad ~ Rego Checks including Duel Fuel, LPG Inspections & Repairs BOUTIQUE FURNITURE AND GIFTS ~ New Car Servicing ~ All Fleet Servicing ~ All General Repairs (Cars, Trucks & 4WD) A. -

TORCHWOOD T I M E L I N E DRAMA I 2 K S 2 Sunday BBC3, Wednesday BBC2 ~*T0&> ' ""* Doctor Who Viewers Have Hear

DRAMA SundayI2KS BBC3,2 Wednesday BBC2 TORCHWOOD TIMELINE ~*t0&> ' ""* Doctor Who viewers have heard the name Torchwood before... 11 Jure 2005 In the series one episode It may be a Doctor Who spin-off, but Torchwood Sad Wolf, Torchwood is an is very much its own beast, says Russell T Davies answer on Weakest Link with Anne-droid (pictured above). % Jack's back. But he's changed - he's of course, their leader, and two of the other angrier. The last we saw of Captain actors have also appeared in Doctor Who: Eve 25 December 2005 Jack Harkness, at the tail end of the Myles, who played Victorian maid Gwyneth In The Christmas Invasion, Prime Minister Harriet Jones rejuvenated Doctor Who series one, he'd in The Unquiet Dead; and Naoko Mori continues reveals she knows about top- been exterminated by Daleks (see picture to play the role of Dr Toshiko Sato, last seen secret Torchwood - and orders below), been brought back to life and then examining a pig in a spacesuit in Aliens of London. it to destroy the Sycorax ship. abandoned by the Doctor to fend for himself. As you'll see from the cover and our profile on What does a flirtatious, sexy-beast Time Agent page 14, they're a glamorous bunch. Or, as 22 April 2006 from the 51 st century, understandably miffed at Myles puts it, "It's a very sexy world." In Tooth and Claw, set in being dumped, do next? Easy: he joins Torchwood. Their objective? Nothing less than keeping the Torchwood House, Queen Doctor Who fans - and there are a few - will world safe from alien threat. -

Sociopathetic Abscess Or Yawning Chasm? the Absent Postcolonial Transition In

Sociopathetic abscess or yawning chasm? The absent postcolonial transition in Doctor Who Lindy A Orthia The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia Abstract This paper explores discourses of colonialism, cosmopolitanism and postcolonialism in the long-running television series, Doctor Who. Doctor Who has frequently explored past colonial scenarios and has depicted cosmopolitan futures as multiracial and queer- positive, constructing a teleological model of human history. Yet postcolonial transition stages between the overthrow of colonialism and the instatement of cosmopolitan polities have received little attention within the program. This apparent ‘yawning chasm’ — this inability to acknowledge the material realities of an inequitable postcolonial world shaped by exploitative trade practices, diasporic trauma and racist discrimination — is whitewashed by the representation of past, present and future humanity as unchangingly diverse; literally fixed in happy demographic variety. Harmonious cosmopolitanism is thus presented as a non-negotiable fact of human inevitability, casting instances of racist oppression as unnatural blips. Under this construction, the postcolonial transition needs no explication, because to throw off colonialism’s chains is merely to revert to a more natural state of humanness, that is, cosmopolitanism. Only a few Doctor Who stories break with this model to deal with the ‘sociopathetic abscess’ that is real life postcolonial modernity. Key Words Doctor Who, cosmopolitanism, colonialism, postcolonialism, race, teleology, science fiction This is the submitted version of a paper that has been published with minor changes in The Journal of Commonwealth Literature, 45(2): 207-225. 1 1. Introduction Zargo: In any society there is bound to be a division. The rulers and the ruled. -

Songs by Jim Steinman

Total Eclipse of the Charts SONGS BY JIM STEINMAN For over 35 years, legendary songwriter/producer Jim Steinman (aka Little Richard Wagner) has been rocking our world like no other... BAT OUT OF HELL The classic Meat Loaf album is currently in the all-time top 3 of global record sales at 43 million and counting, and the only album in the top 20 written entirely by ONE individual. In addition to the epic title track, other great songs include Two Out Of Three ‘Aint Bad, Paradise By The Dashboard Light and Heaven Can Wait. BAT OUT OF HELL 2 The album that reunited Jim & Meat after 16 years apart, this 11 song sequel was once again written entirely by ONE individual. The huge lead single I’d Do Anything For Love (But I Won’t Do That) earned a Grammy for ‘best rock vocal’ and helped launch the album to global sales exceeding 14 million. Other mini-operas on the album include Rock & Roll Dreams Come Through, Life Is A Lemon & I Want My Money Back and the epic that ‘out epics’ everything else… …Objects In The Rear View Mirror May Appear Closer Than They Are. TOTAL ECLIPSE OF THE HEART Taken from the Steinman produced album Faster Than The Speed Of Night, this 1983 worldwide smash for Bonnie Tyler hit # 1 in the US & UK, with global sales now exceeding 9 million. The power ballad to end all power ballads…’turnaround bright eyes’! IT’S ALL COMING BACK TO ME NOW Written whilst under the influence ofWuthering Heights, this US # 1 for Celine Dion earned Jim the BMI ‘song of the year’ award in 1998. -

Quartet March2020

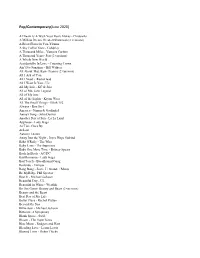

Pop/Contemporary (June 2020) A Dream Is A Wish Your Heart Makes - Cinderella A Million Dream Greatest Showman (2 versions) A River Flows in You-Yiruma A Sky Full of Stars - Coldplay A Thousand Miles - Vanessa Carlton A Thousand Years- Peri (2 versions) A Whole New World Accidentally In Love - Counting Crows Ain't No Sunshine - Bill Withers All About That Bass- Trainor (2 versions) All I Ask of You All I Need - RadioHead All I Want Is You - U2 All My Life - KC & Jojo All of Me- John Legend All of My love All of the Lights - Kayne West All The Small Things - Blink 182 Always - Bon Jovi America - Simon & Garfunkel Annie's Song - John Denver Another Day of Sun - La La Land Applause - Lady Gaga As Time Goes By At Last Autumn Leaves Away Into the Night - Joyce Hope Siskind Baba O'Reily - The Who Baby Love - The Supremes Baby One More Time - Britney Spears Back In Black - AC/DC Bad Romance - Lady Gaga Bad Touch - Bloodhound Gang Bailando - Enrique Bang Bang - Jessie J / Grande / Minaj Be MyBaby- Phil Spector Beat It - Michael Jackson Beautiful Day - U2 Beautiful in White - Westlife Be Our Guest- Beauty and Beast (2 versions) Beauty and the Beast Best Day of My Life Better Place - Rachel Platten Beyond the Sea Billie Jean - Michael Jackson Bittersweet Symphony Blank Space - Swift Bloom - The Paper Kites Blue Moon - Rodgers and Hart Bleeding Love - Leona Lewis Blurred Lines - Robin Thicke Bohemian Rapsody-Queen Book of Days - Enya Book of Love - Peter Gabriel Boom Clap - Charli XCX Brown Eyed Girl - Van Morrison Budapest - Geo Ezra Buddy Holly- -

ARTHUR AROHA KAMINSKI DA SILVA.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARANÁ ARTHUR AROHA KAMINSKI DA SILVA UM OCEANO DE HESITAÇÕES: AS CONSTITUIÇÕES DO EU E DO FANTÁSTICO EM O OCEANO NO FIM DO CAMINHO DE NEIL GAIMAN. CURITIBA 2018 ARTHUR AROHA KAMINSKI DA SILVA UM OCEANO DE HESITAÇÕES: AS CONSTITUIÇÕES DO EU E DO FANTÁSTICO EM O OCEANO NO FIM DO CAMINHO DE NEIL GAIMAN. Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Letras, do Setor de Ciências Humanas da Universidade Federal do Paraná (PPGL/UFPR), como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de Mestre em Letras na área de Estudos Literários. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Alexandre André Nodari. CURITIBA 2018 FICHA CATALOGRÁFICA ELABORADA PELO SISTEMA DE BIBLIOTECAS/ UFPR COM OS DADOS FORNECIDOS PELO (A) AUTOR(A) BIBLIOTECA DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS BIBLIOTECÁRIO: RITA DE CÁSSIA ALVES DE SOUZA – CRB-9/ 816 Silva, Arthur Aroha Kaminski da. Um oceano de hesitações : as constituições do eu e do fantástico em O oceano no fim do caminho de Neil Gaiman / Arthur Aroha Kaminski da Silva. – Curitiba, 2018. 263 f. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Universidade Federal do Paraná. Setor de Ciências Humanas, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Alexandre André Nodari. AGRADECIMENTOS Esta dissertação foi escrita em dois lugares, e consequentemente foi influenciada por diversas pessoas e seres aos quais devo agradecer. Uma primeira parte das ideias aqui contidas foi discutida e produzida nas cercanias de um edifício que frequento desde que tinha cinco anos, e ao qual, de tempos em tempos, sempre pareço voltar: a reitoria da UFPR, no centro de Curitiba, capital paranaense. Este curioso espaço, com seus numerosos e congelantes corredores de pedra, seus excêntricos frequentadores, suas inconfundíveis e intermináveis rampas, e seu aprazível pátio onde se praticam obscuros esportes, sempre se constituiu para mim como uma espécie de segunda casa, e eu posso afirmar, sem sombra de dúvidas, de que foi lá que, em grande medida, eu cresci. -

Doctor Who and the Creation of a Non-Gendered Hero Archetype

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 10-13-2014 Doctor Who and the Creation of a Non-Gendered Hero Archetype Alessandra J. Pelusi Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Pelusi, Alessandra J., "Doctor Who and the Creation of a Non-Gendered Hero Archetype" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 272. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/272 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DOCTOR WHO AND THE CREATION OF A NON-GENDERED HERO ARCHETYPE Alessandra J. Pelusi 85 Pages December 2014 This thesis investigates the ways in which the television program Doctor Who forges a new, non-gendered, hero archetype from the amalgamation of its main characters. In order to demonstrate how this is achieved, I begin with reviewing some of the significant and relevant characters that contribute to this. I then examine the ways in which female and male characters are represented in Doctor Who, including who they are, their relationship with the Doctor, and what major narrative roles they play. I follow this with a discussion of the significance of the companion, including their status as equal to the Doctor. From there, I explore the ways in which the program utilizes existing archetypes by subverting them and disrupting the status quo.