"Secular Humanism": a Blight on the Establishment Clause Linda Eigner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HUMANISM Religious Practices

HUMANISM Religious Practices . Required Daily Observances . Required Weekly Observances . Required Occasional Observances/Holy Days Religious Items . Personal Religious Items . Congregate Religious Items . Searches Requirements for Membership . Requirements (Includes Rites of Conversion) . Total Membership Medical Prohibitions Dietary Standards Burial Rituals . Death . Autopsies . Mourning Practices Sacred Writings Organizational Structure . Headquarters Location . Contact Office/Person History Theology 1 Religious Practices Required Daily Observance No required daily observances. Required Weekly Observance No required weekly observances, but many Humanists find fulfillment in congregating with other Humanists on a weekly basis (especially those who characterize themselves as Religious Humanists) or other regular basis for social and intellectual engagement, discussions, book talks, lectures, and similar activities. Required Occasional Observances No required occasional observances, but some Humanists (especially those who characterize themselves as Religious Humanists) celebrate life-cycle events with baby naming, coming of age, and marriage ceremonies as well as memorial services. Even though there are no required observances, there are several days throughout the calendar year that many Humanists consider holidays. They include (but are not limited to) the following: February 12. Darwin Day: This marks the birthday of Charles Darwin, whose research and findings in the field of biology, particularly his theory of evolution by natural selection, represent a breakthrough in human knowledge that Humanists celebrate. First Thursday in May. National Day of Reason: This day acknowledges the importance of reason, as opposed to blind faith, as the best method for determining valid conclusions. June 21 - Summer Solstice. This day is also known as World Humanist Day and is a celebration of the longest day of the year. -

INTRODUCTION 1. Medical Humanism and Natural Philosophy

INTRODUCTION 1. Medical Humanism and Natural Philosophy The Renaissance was one of the most innovative periods in Western civi- lization.1 New waves of expression in fijine arts and literature bloomed in Italy and gradually spread all over Europe. A new approach with a strong philological emphasis, called “humanism” by historians, was also intro- duced to scholarship. The intellectual fecundity of the Renaissance was ensured by the intense activity of the humanists who were engaged in collecting, editing, translating and publishing the ancient literary heri- tage, mostly in Greek and Latin, which had hitherto been scarcely read or entirely unknown to the medieval world. The humanists were active not only in deciphering and interpreting these “newly recovered” texts but also in producing original writings inspired by the ideas and themes they found in the ancient sources. Through these activities, Renaissance humanist culture brought about a remarkable moment in Western intel- lectual history. The effforts and legacy of those humanists, however, have not always been appreciated in their own right by historians of philoso- phy and science.2 In particular, the impact of humanism on the evolution of natural philosophy still awaits thorough research by specialists. 1 By “Renaissance,” I refer to the period expanding roughly from the fijifteenth century to the beginning of the seventeenth century, when the humanist movement begun in Italy was difffused in the transalpine countries. 2 Textbooks on the history of science have often minimized the role of Renaissance humanism. See Pamela H. Smith, “Science on the Move: Recent Trends in the History of Early Modern Science,” Renaissance Quarterly 62 (2009), 345–75, esp. -

A Short Course on Humanism

A Short Course On Humanism © The British Humanist Association (BHA) CONTENTS About this course .......................................................................................................... 5 Introduction – What is Humanism? ............................................................................. 7 The course: 1. A good life without religion .................................................................................... 11 2. Making sense of the world ................................................................................... 15 3. Where do moral values come from? ........................................................................ 19 4. Applying humanist ethics ....................................................................................... 25 5. Humanism: its history and humanist organisations today ....................................... 35 6. Are you a humanist? ............................................................................................... 43 Further reading ........................................................................................................... 49 33588_Humanism60pp_MH.indd 1 03/05/2013 13:08 33588_Humanism60pp_MH.indd 2 03/05/2013 13:08 About this course This short course is intended as an introduction for adults who would like to find out more about Humanism, but especially for those who already consider themselves, or think they might be, humanists. Each section contains a concise account of humanist The unexamined life thinking and a section of questions -

Was Immanuel Kant a Humanist? This Article Continues FI 'S Ongoing Series on the Precursors of Modern-Day Humanism

Was Immanuel Kant a Humanist? This article continues FI 's ongoing series on the precursors of modern-day humanism. Finngeir Hiorth erman philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) is can be found in antiquity, the proofs were mainly developed generally regarded to be one of the greatest philos- in the Middle Ages. And during this time Thomas Aquinas Gophers of the Western world. His reputation is based was their major advocate and systematizer. mainly on his contributions to the theory of knowledge and Kant undertook a new classification of the proofs, or to moral philosophy, although he also has contributed to other arguments, as we shall call them. He distinguished between parts of philosophy, including the philosophy of religion. Kant ontological, cosmological, and physico-theological arguments, was a very original philosopher, and his historical importance and rejected them. He believed that there were no other is beyond any doubt. And although some contemporary arguments of importance. Thus, for Kant, it was impossible humanists do not share the general admiration for Kant, he to prove the existence of God. to some extent, remains important for modern humanism. God's position was not improved in Kant's next important Kant is sometimes regarded to be the philosopher of the publication, Foundation of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785). Protestants, just as Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) is considered In this rather slim (about seventy pages) publication, Kant to be the philosopher of the Catholics. One might think a gave an analysis of the foundation of ethics. What is philosopher who is important to Protestantism is an unlikely remarkable from a humanistic point of view is that God is candidate for a similar position among secular humanists. -

What Is Atheism, Secularism, Humanism? Academy for Lifelong Learning Fall 2019 Course Leader: David Eller

What is Atheism, Secularism, Humanism? Academy for Lifelong Learning Fall 2019 Course leader: David Eller Course Syllabus Week One: 1. Talking about Theism and Atheism: Getting the Terms Right 2. Arguments for and Against God(s) Week Two: 1. A History of Irreligion and Freethought 2. Varieties of Atheism and Secularism: Non-Belief Across Cultures Week Three: 1. Religion, Non-religion, and Morality: On Being Good without God(s) 2. Explaining Religion Scientifically: Cognitive Evolutionary Theory Week Four: 1. Separation of Church and State in the United States 2. Atheist/Secularist/Humanist Organization and Community Today Suggested Reading List David Eller, Natural Atheism (American Atheist Press, 2004) David Eller, Atheism Advanced (American Atheist Press, 2007) Other noteworthy readings on atheism, secularism, and humanism: George M. Smith Atheism: The Case Against God Richard Dawkins The God Delusion Christopher Hitchens God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything Daniel Dennett Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon Victor Stenger God: The Failed Hypothesis Sam Harris The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Religion Michael Martin Atheism: A Philosophical Justification Kerry Walters Atheism: A Guide for the Perplexed Michel Onfray In Defense of Atheism: The Case against Christianity, Judaism, and Islam John M. Robertson A Short History of Freethought Ancient and Modern William Lane Craig and Walter Sinnott-Armstrong God? A Debate between a Christian and an Atheist Phil Zuckerman and John R. Shook, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Secularism Janet R. Jakobsen and Ann Pellegrini, eds. Secularisms Callum G. Brown The Death of Christian Britain: Understanding Secularisation 1800-2000 Talal Asad Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity Lori G. -

Contested Authorities Over Life Politics: Religious

CONTESTED AUTHORITIES OVER LIFE POLITICS: RELIGIOUS-SECULAR TENSIONS IN ABORTION DEBATES IN GERMANY, TURKEY, AND ISRAEL1 Gökce Yurdakul, Professor of Sociology, Humboldt University of Berlin Gala Rexer, Doctoral Researcher, Humboldt University of Berlin Nil Mutluer, Einstein Senior Fellow, Humboldt University of Berlin Shvat Eilat, Doctoral Researcher, Department of Sociology and Anthroplogy, Tel Aviv University Abstract Conflicts between religious and secular discourses, norms, actors, and institutions are differently shaped across the Middle East and Europe in accordance with their specific socio- legal contexts. While current scholarship has often studied this tension by focusing on religious rituals, we shed new light on the way religion and secularity shape the everyday making of life politics by way of a three-country comparison of abortion debates in Germany, Turkey, and Israel. Through face-to-face interviews with stakeholders involved in interpreting secular abortion law, we analyze how social actors in three predominantly monotheistic countries and 1 This article is written as a part of a larger research project on contested authority in body politics which compares religious-secular tensions on male circumcision, abortion, and posthumous organ donation, led by equal PIs Gökce Yurdakul and Shai Lavi, funded by the German-Israeli Foundation Regular Grant (2016 through 2019). We thank our research assistants, who conducted interviews in three countries: David Schulz (Germany); Burcu Halaç and Emine Uçak (Turkey); Shvat Eilat and Gala Rexer (Israel). Nil Mutluer’s research has been supported by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation’s Philipp-Schwartz Scholarship for Scholars at Risk (2017 through 2019). Anna Korteweg, Sharon Orshalimy, Kinneret Lahad and two anonymous reviewers commented on the earlier versions of this article. -

Introduction: the Emerging Alliance of World Religions and Ecology

Emerging Alliance of World Religions and Ecology 1 Mary Evelyn Tucker and John A. Grim Introduction: The Emerging Alliance of World Religions and Ecology HIS ISSUE OF DÆDALUS brings together for the first time diverse perspectives from the world’s religious traditions T regarding attitudes toward nature with reflections from the fields of science, public policy, and ethics. The scholars of religion in this volume identify symbolic, scriptural, and ethical dimensions within particular religions in their relations with the natural world. They examine these dimensions both historically and in response to contemporary environmental problems. Our Dædalus planning conference in October of 1999 fo- cused on climate change as a planetary environmental con- cern.1 As Bill McKibben alerted us more than a decade ago, global warming may well be signaling “the end of nature” as we have come to know it.2 It may prove to be one of our most challenging issues in the century ahead, certainly one that will need the involvement of the world’s religions in addressing its causes and alleviating its symptoms. The State of the World 2000 report cites climate change (along with population) as the critical challenge of the new century. It notes that in solving this problem, “all of society’s institutions—from organized re- ligion to corporations—have a role to play.”3 That religions have a role to play along with other institutions and academic disciplines is also the premise of this issue of Dædalus. The call for the involvement of religion begins with the lead essays by a scientist, a policy expert, and an ethicist. -

Janne Kontala – EMERGING NON-RELIGIOUS WORLDVIEW PROTOTYPES

Janne Kontala | Emerging Non-religious Worldview Prototypes | 2016 Prototypes Worldview Non-religious Janne Kontala | Emerging Janne Kontala Emerging Non-religious Worldview Prototypes A Faith Q-sort-study on Finnish Group-affiliates 9 789517 658386 ISBN 978-951-765-838-6 Åbo Akademis förlag Domkyrkotorget 3, FI-20500 Åbo, Finland Tfn +358 (0)2 215 4793 E-post: forlaget@abo. Försäljning och distribution: Åbo Akademis bibliotek Domkyrkogatan 2-4, FI-20500 Åbo, Finland Tfn +358 (0)2 215 4190 E-post: publikationer@abo. EMERGING NON-RELIGIOUS WORLDVIEW PROTOTYPES Emerging Non-religious Worldview Prototypes A Faith Q-sort-study on Finnish Group-affiliates Janne Kontala Åbo Akademis förlag | Åbo Akademi University Press Åbo, Finland, 2016 CIP Cataloguing in Publication Kontala, Janne. Emerging non-religious worldview prototypes : a faith q-sort-study on Finnish group-affiliates / Janne Kontala. - Åbo : Åbo Akademi University Press, 2016. Diss.: Åbo Akademi University. ISBN 978-951-765-838-6 ISBN 978-951-765-838-6 ISBN 978-951-765-839-3(digital) Painosalama Oy Åbo 2016 ABSTRACT This thesis contributes to the growing body of research on non-religion by examining shared and differentiating patterns in the worldviews of Finnish non-religious group-affiliates. The organisa- tions represented in this study consist of the Union of Freethinkers, Finland’s Humanist Association, Finnish Sceptical Society, Prometheus Camps Support Federation and Capitol Area Atheists. 77 non-randomly selected individuals participated in the study, where their worldviews were analysed with Faith Q-sort, a Q-methodological application designed to assess subjectivity in the worldview domain. FQS was augmented with interviews to gain additional information about the emerging worldview prototypes. -

Augustine's Contribution to the Republican Tradition

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Peer Reviewed Articles Political Science and International Relations 2010 Augustine’s Contribution to the Republican Tradition Paul J. Cornish Grand Valley State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/pls_articles Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Cornish, Paul J., "Augustine’s Contribution to the Republican Tradition" (2010). Peer Reviewed Articles. 10. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/pls_articles/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Political Science and International Relations at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peer Reviewed Articles by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. article Augustine’s Contribution to the EJPT Republican Tradition European Journal of Political Theory 9(2) 133–148 © The Author(s), 2010 Reprints and permission: http://www. Paul J. Cornish Grand Valley State University sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav [DOI: 10.1177/1474885109338002] http://ejpt.sagepub.com abstract: The present argument focuses on part of Augustine’s defense of Christianity in The City of God. There Augustine argues that the Christian religion did not cause the sack of Rome by the Goths in 410 ce. Augustine revised the definitions of a ‘people’ and ‘republic’ found in Cicero’s De Republica in light of the impossibility of true justice in a world corrupted by sin. If one returns these definitions ot their original context, and accounts for Cicero’s own political teachings, one finds that Augustine follows Cicero’s republicanism on several key points. -

Liberal Humanism and Its Effect on the Various Contemporary Educational Approaches

International Education Studies; Vol. 8, No. 3; 2015 ISSN 1913-9020 E-ISSN 1913-9039 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Liberal Humanism and Its Effect on the Various Contemporary Educational Approaches Zargham Yousefi1, Alireza Yousefy2 & Narges Keshtiaray1 1 Department of Educational Sciences, Isfahan (Khorasgan) Branch, Islamic Azad University, Isfahan, Iran 2 Medical Education Research Centre, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran Correspondence: Alireza Yousefy, Medical Education Research Centre, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. E-mail: [email protected] Received: October 16, 2014 Accepted: November 20, 2014 Online Published: February 25, 2015 doi:10.5539/ies.v8n3p103 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ies.v8n3p103 Abstract Liberalism is one of the main western doctrines which have originated from the ideologies of ancient Greece. The concept of humanism has been under the influence of liberal ideas in different political, social, economic and especially educational field. Since the educational field concerned with liberal ideologies, the study of different factors affecting liberal humanism helps distinguishing the concepts explained by each approaches and their similarities and differences. In this qualitative research, it has been endeavored to determine each of these aspects and factors and their effect on various contemporary educational approaches. The results indicate that some of the main factors of liberal humanism have not been considered and in the cases that they have been considered, the understandings of common subjects are different. Each of these approaches tends to study and define the aspects and principles from a certain point of view. Keywords: liberalism, humanism, education, contemporary educational approaches 1. -

Schooling and Religion: a Secular Humanist View

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 320 283 EA 021 949 AUTHOR Bauer, Norman J. TITLE Schooling and Religion: A Secular Humanist View. PUB DATE Oct 89 NOTE 23p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Studies Association (Chicago, IL, October 25-26, 1989). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150)-- Reports - Evaluative /Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Educational Philosophy; Elementary Secondary Education; *Humanism; Religion Studies; *Religious Education; State Church Separation ABSTRACT The proper relation between religion and public schooling is addressed in this paper which reviews the secular humanist position and recommends ways to pursue the study of religion in classrooms. This dual purpose is achieved through thefollowing process: (1) reconstruction of an empirical-naturalistic image of reality (Image 1); (2) construction of an image of reflective thought, which is the product of this view of reality (Image 2);and (3) examination of the implications of the twoimages for the philosophy of education, sociopolitical order, and curricular content, organization, and implementation. The secular humanist position is not foreign to the notion of religious ideas and values. Images 1 and 2 stress the contemporary secular humanists' optimistic belief in human nature and scientific reason for the attainmentof human fulfillment. This position is compatible with the stanceheld by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution for theintegration of religious study within public schools. (17 references) (LMI) * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be ma.e * * from the original document. * SCHOOLING AND RELIGION: A SECULAR HUMANIST VIEW Norman J. Bauer, Ed.D. Professor of Education State University of New York Geneseo, New York U S DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of EducahOnal Research and Improvement "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCETHIS URIC IONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTEDBY CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproduced as . -

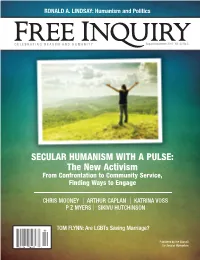

SECULAR HUMANISM with a PULSE: the New Activism from Confrontation to Community Service, Finding Ways to Engage

FI AS C1_Layout 1 6/28/12 10:45 AM Page 1 RONALD A. LINDSAY: Humanism and Politics CELEBRATING REASON AND HUMANITY August/September 2012 Vol. 32 No.5 SECULAR HUMANISM WITH A PULSE: The New Activism From Confrontation to Community Service, Finding Ways to Engage CHRIS MOONEY | ARTHUR CAPLAN | KATRINA VOSS P Z MYERS | SIKIVU HUTCHINSON 09 TOM FLYNN: Are LGBTs Saving Marriage? Published by the Council for Secular Humanism 7725274 74957 FI Aug Sept CUT_FI 6/27/12 4:54 PM Page 3 August/September 2012 Vol. 32 No. 5 CELEBRATING REASON AND HUMANITY 20 Secular Humanism With A Pulse: 30 Grief Beyond Belief The New Activists Rebecca Hensler Introduction Lauren Becker 32 Humanists Care about Humans! Bob Stevenson 22 Sparking a Fire in the Humanist Heart James Croft 34 Not Enough Marthas Reba Boyd Wooden 24 Secular Service in Michigan Mindy Miner 35 The Making of an Angry Atheist Advocate EllenBeth Wachs 25 Campus Service Work Franklin Kramer and Derek Miller 37 Taking Care of Our Own Hemant Mehta 27 Diversity and Secular Activism Alix Jules 39 A Tale of Two Tomes Michael B. Paulkovich 29 Live Well and Help Others Live Well Bill Cooke EDITORIAL 15 Who Cares What Happens 56 The Atheist’s Guide to Reality: 4 Humanism and Politics to Dropouts? Enjoying Life without Illusions Ronald A. Lindsay Nat Hentoff by Alex Rosenberg Reviewed by Jean Kazez LEADING QUESTIONS 16 CFI Gives Women a Voice with 7 The Rise of Islamic Creationism, Part 1 ‘Women in Secularism’ Conference 58 What Jesus Didn’t Say A Conversation with Johan Braeckman Julia Lavarnway by Gerd Lüdemann Reviewed by Robert M.