Michal Vojtas-Reviving Don Boscos Oratory.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LA No School No School Name 100% 340 3307 Holy Family Catholic

LA School School Name 100% No No 340 3307 Holy Family Catholic Primary School £ 11,920.32 340 3314 Our Lady's Catholic Primary School £ 12,259.30 340 3315 St Luke's Catholic Primary School £ 12,035.88 340 3316 St Laurence's Catholic Primary School £ 18,037.30 340 3318 St Aidan's Catholic Primary School £ 11,766.24 340 3319 St Michael and All Angels Catholic Primary School £ 18,514.94 340 3322 St Marie's Catholic Primary School £ 13,961.88 340 3325 St Albert's Catholic Primary School £ 11,673.79 340 3326 Holy Family Catholic Primary School £ 15,510.39 340 3327 St Mark's Catholic Primary School £ 11,473.49 340 3328 St Andrew the Apostle Catholic Primary School £ 12,026.63 340 3340 St Joseph's Catholic Primary School £ 11,535.12 340 3344 St Brigid's Catholic Primary School £ 10,726.20 340 3350 St Leo's and Southmead Catholic Primary School £ 11,434.97 340 3352 St John Fisher Catholic Primary School £ 11,072.88 340 3353 St Anne's Catholic Primary School £ 15,233.04 340 3356 Saints Peter and Paul Catholic Primary School £ 15,826.24 340 3357 St Columba's Catholic Primary School £ 11,951.13 340 3358 St Margaret Mary's Catholic Infant School £ 19,747.59 340 3359 St Margaret Mary's Catholic Junior School £ 21,897.00 340 3360 St Aloysius Catholic Primary School £ 16,573.53 340 3361 St Joseph the Worker Catholic Primary School £ 12,552.04 340 4615 All Saints Catholic High School £ 53,868.60 340 4616 St Edmund Arrowsmith Catholic Centre for Learning (VA) £ 61,322.22 341 2006 All Saints' Catholic VA Primary School £ 20,652.80 341 2025 Blessed Sacrament -

Holy Week 2021: Everything We Do During This Lent

Holy Week 2021: Everything we do during Families may wish to bring their own this Lent, points us toward the celebration of branches (palm, or olive or something else) Holy Week which ends with the victory of so we don’t have to share palms. Christ over death. This year all of our Holy Week celebrations will be outside and will Holy Thursday: We remember the Lord’s last take into account the limitations that the supper and the gift of the Holy Eucharist. Like pandemic has required. Please remember to last year, I invite families to bring to our bring you own chair to our outdoor evening service, a basket oF bread. It will be services. blessed at the beginning of the Mass and you’ll be able to take it home for your family’s Palm Sunday: evening meal. Traditionally after this evening (regular weekend schedule of masses) celebration, churches are open for adoration. Like last year, our adoration will be on-line Service will be live-streamed and can be from about 8:30 pm to 9:30 pm. seen at: www.saintdominicsavio.org Good Friday: We remember the passion and Holy Thursday: 5:00 pm English death of Jesus. The service consists of the Jueves Santo 7:00 pm Spanish proclamation of the Passion according to St. John, the Veneration of the Cross, and Holy Good Friday: 5:00 pm English Communion. Because of the pandemic, we will Viernes Santo 7:00 pm Spanish not be kissing the Cross but we will use Easter Vigil 5:00 pm English another form of veneration. -

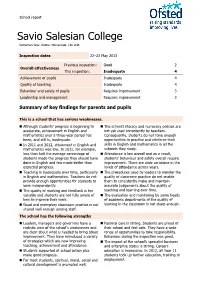

Savio Salesian College Netherton Way, Bootle, Merseyside, L30 2NA

School report Savio Salesian College Netherton Way, Bootle, Merseyside, L30 2NA Inspection dates 22–23 May 2013 Previous inspection: Good 2 Overall effectiveness This inspection: Inadequate 4 Achievement of pupils Inadequate 4 Quality of teaching Inadequate 4 Behaviour and safety of pupils Requires improvement 3 Leadership and management Requires improvement 3 Summary of key findings for parents and pupils This is a school that has serious weaknesses. Although students’ progress is beginning to The school’s literacy and numeracy policies are accelerate, achievement in English and not yet used consistently by teachers. mathematics over a three-year period has Consequently, students do not have enough been, and still is, inadequate. opportunities to practise and reinforce their In 2011 and 2012, attainment in English and skills in English and mathematics in all the mathematics was low. In 2012, for example, subjects they study. less than half the average percentage of Attendance is low overall and as a result, students made the progress they should have students’ behaviour and safety overall require done in English and few made better than improvement. There are wide variations in the expected progress. levels of attendance across years. Teaching is inadequate over time, particularly The procedures used by leaders to monitor the in English and mathematics. Teachers do not quality of classroom practice do not enable provide enough opportunities for students to them to consistently make and maintain learn independently. accurate judgements about the quality of The quality of marking and feedback is too teaching and learning over time. variable and students are not fully aware of The evaluation and monitoring by some heads how to improve their work. -

1. September 12, 1994: Official Beginning, Back to Don Viganò

Secolarità Consacrata Salesiana Secularidad Consagrada Salesiana Secularitè Consacrée Salésiènne Secularidade Consagrada Salesiana N. 5 Salesian Consecrated Life in Secular Institutes September 2019 SCS Saleziánska zasvätená sekulárnosť Number extra Salezjańska Świeckość Konsekrowana More seeds… One same precious gift: Memory and prophecy A fraternal welcome to a specific vocation Of the Volunteers with Don Bosco (CDB) We, Volunteers with Don Bosco (CDB) are in a feast. Out Institute, part of the Salesian Family from its beginning, celebrates its Silver Jubilee: Twenty-five years for God and for the world. In a simple, silent but extraordinarily lively and grateful way, all of us feel that we are instruments of Divine Providence. God has done great deeds in us from the first years in which the desire to live our Baptism with the radicality of the consecrated life with Salesian style in the world materialized in the hands of Fr Egidio Viganò, until today when we are reflecting on the expansion of the Institute in so many parts of the world. Permit me to be present in your community with this meditation proposal, to share with you our being and our mission in an atmosphere of prayer and of discernment. It is in this way that our vocation and our group was born. To recall and relive these first moments in the light of the Word of God and in the reality of the Church today will enable us to remain profoundly passionate about youth, about the Church and about the world: We as consecrated laity in the world; and you, as the heirs of a charism which the Holy Spirit had deposited in the heart of Don Bosco. -

Dai Consiglieri Professionali Generali Alla Federazione Nazionale CNOS-FAP

Dai Consiglieri Professionali Generali alla Federazione Nazionale CNOS-FAP Felice Rizzini Il processo innovativo della Formazione Professionale s'intensificò dopo la morte dì Don Bosco per il contributo determinante dei Consiglieri Professionali Generali, per gli interventi dei Capitoli Generali e per la dedizione alla causa da par te dei Salesiani Coadiutori, in parallelo agli interventi legislativi e normativi dello Stato ed allo spazio maggiore dato ad essa dalle iniziative pubbliche e private. Dopo Don Giuseppe Lazzero, che per primo esercitò il compito di Consigliere Generale Professionale della Congregazione dal 1886 al 1898, distinguendosi nella cura particolare alla formazione dei Coadiutori Salesiani, si succedettero: Don Giu seppe Bertello (1898-1910); Don Giuseppe Vespignani (una prima volta dal 1910 al 1911 ed una seconda volta dal 1922 al 32); Don Pietro Ricaldone (1911-1922); Don Antonio Candela (1932-1958); Don Ernesto Giovannini (1959-1965). Con il Capi tolo Generale XIX venne abolita la figura del Consigliere Professionale Generale. Fra di essi si distinsero per l'impulso dato alle Scuole Salesiane Professionali e Agra rie Don Giuseppe Bertello, Don Pietro Ricaldone, Don Antonio Candela e Don Ernesto Giovannini. 1 — Don Giuseppe Bertello Don Bertello arrivò a tale incarico con una profonda preparazione umanistica (laureato in teologia, in lettere e filosofia, membro dell'Arcadia e dell'Accademia Romana di S. Tommaso) e con una ricca esperienza di governo come direttore ed 127 ispettore, ma senza una preparazione specifica. Cercò di superare questo limite con lo studio personale e con il contatto diretto con l'esperienze salesiane e con quelle più importanti maturate in quel tempo in Italia e all'estero. -

Bollettino Salesiano

2015 - Digital Collections - Biblioteca Don Bosco - Roma - http://digital.biblioteca.unisal.it IN QUESTO NUMERO : Il nuovo Rettor Maggiore Don Luigi Ricceri pag. 161 "Pietro è qui " Identificate le ossa di San Pietro pag. 165 Che fanno i ragazzi in Colonia? pag. 172 Da 50 anni i Missionari salesiani IN COPERTINA • Una delle numerose fan- lavorano nel Rio Negro fare dei collegi e oratori salesiani del Congo pag. 185 Servizio sul Congo a pag . 183 Milletrecento ragazzi francesi, belgi, svizzeri « in marcia verso Domenico » 2015 - Digital Collections - Biblioteca Don Bosco - Roma - http://digital.biblioteca.unisal.it Don Bosco ha successoreil suo sesto Alle ore 12,10 del 27 aprile scorso, una nuova mano ha impugnato il timone della Congre- gazione Salesiana. DoN LUIGI RICCERI, salutato dagli applausi cordiali dei 150 capitolari che lo avevano voluto sesto Successore di San Giovanni Bosco . In quel momento cercò inu- tilmente di dominare la sua commozione, mentre i capitolari scavalcando il protocollo si assiepavano intorno a lui per avvolgerlo in un abbraccio affettuoso e per dirgli la loro gioia «Vogliamo formare una grande famiglia » L'intensa mattinata era cominciata ai piedi del- Con questa certezza i capitolari passarono nel- l'altare . Nella nuova chiesa dell'Ateneo romano il l'aula magna per la votazione . A uno a uno giura- Rettor Maggiore uscente don Ziggiotti celebrò la rono, con la mano posata sul Vangelo, di dare il Messa per invocare l'assistenza dello Spirito Santo . voto libero e segreto a quel superiore che giudicas- Nel Vangelo lesse le parole di Gesù : « Lo Spirito sero di eleggere al cospetto di Dio . -

Saint Dominic Savio

Saint Dominic Savio Dominic Savio is one of the few teenage saints in the history of the Church. He was born in 1842 in the village of Riva in northern Italy. He was the eldest child of Charles and Brigid Savio who were poor and hard working people. At the age of 8 Dominic walked ten kilometres each day to the school in the neighbouring village. There he became an excellent student who always tried hard in his lessons. At the age of 12 he commenced at Don Bosco's school, The Oratory of St Francis de Sales in Turin. He made many friends due to his cheerfulness and willingness to be part of every activity. Dominic was a gifted student leader. At school he would actively look out for those who were lonely and befriend them. When a new student arrived he would be the first to greet them. He would encourage them to be a good Christian, saying that it is "not a matter of doing extraordinary things but of doing ordinary things extraordinarily well." Dominic loved God. He had a strong faith and was actively involved in community service. He was a constant visitor to the school hospital where he would cheer up those who were sick. He and his friends would go into Turin to assist those who were old or ill. Dominic was not a physically strong boy and had bad health. His teachers and friends admired the way he never complained about his sickness. He died at the age of 15. Dominic's life is a great example to young people through his effort at school, his loyalty as a friend, his qualities as a student leader, his service to others and his love of God. -

ST. DOMINIC SAVIO the Little Giant

ST. DOMINIC SAVIO The Little Giant 1. When was St. Dominic Savio born? 2nd April 1842 2. Where was St. Dominic Savio born? San Giovanni di Riva 3. When Dominic was 2 years old, in which village did his family settle?—In Murialdo 4. At what age did Dominic Savio serve Mass? --- 5. 5. Name Dominic‘s Father ---Charles Savio 6. Name Dominic‘s Mother --- Brigid Savio 7. In which year did the parents of Dominic change their home once again ?--- In 1852 8. ―I‘m afraid that your health will prevent your study‖ Who said to whom? --Don Bosco to Dominic 9. For how many months was Dominic at the oratory when he heard a sermon on sanctity? –6 months 10. Why did Dominic one day remove his hat and say something in a low voice? --- Because he had heard the Carter take the name of God in Vain. 11. What were Dominic‘s favorite books?--Lives of Saints who had worked for the salvation of souls. 12. What did Dominic do daily without fail? -- He visited the Blessed Sacrament. 13. Once, on the long, three-mile walk to school, an elderly man asked him whether he was afraid to walk alone so far. What did Dominic say in response? Dominic answered that he was not, because his guardian angel went with him. 14. Before Dominic came to the Oratory how many times was he accustomed to go for Confession and Communion?---Once a Month 15. When were the rules of the Sodality of the Immaculate Conception formed? -- 8th June 1856. -

RSS Vol29 1996 A015 N2

ISSN 0393-3830 RICERCHE STORICHE SALESIANE RIVISTA SEMESTRALE DI STORIA RELIGIOSA E CIVILE 29 ANNO XV - N. 2 LUGLIO-DICEMBRE 1996 LAS - ROMA (29)209_216.QXD 13-03-2006 5:13 Pagina 209 RICERCHE STORICHE SALESIANE RIVISTA SEMESTRALE DI STORIA RELIGIOSA E CIVILE ANNO XV - N. 2 (29) LUGLIO-DICEMBRE 1996 SOMMARIO SOMMARI -SUMMARIES ..................................................................... 211-214 Auguri al nuovo Rettor Maggiore don Juan Edmundo Vecchi ......... 215-216 STUDI STAELENS Freddy, I salesiani di don Bosco e le lotte sociopolitiche in un’epoca di transizione (1891-1918) ..................................... 217-271 DOFF-SOTTA Giovanni, Un contributo di don Carlo Maria Baratta all’azione di riforma della musica sacra in Italia (1877-1905) 273-316 FONTI MALFAIT Daniel - SCHEPENS Jacques, «Il Cristiano guidato alla virtù ed alla civiltà secondo lo spirito di San Vincenzo de’ Paoli» ..... 317-381 NOTE BELLONE Ernesto, L’avv. Felice Masera (1885-1938), primo presi- dente nazionale degli ex-allievi salesiani d’Italia dal 1921 al 1938 383-404 RECENSIONI (v. pag. seg.) NOTIZIARIO .................................................................................... 413-414 INDICE GENERALE DELLE ANNATE 1994, 1995, 1996 ........... 415-419 (29)209_216.QXD 13-03-2006 5:13 Pagina 210 RECENSIONI José Díaz COTÁN, La Familia Salesiana en Córdoba (Noventa años de vida apo- stólica) (A. da Silva Ferreira), pp. 405-408; Hugo Pedro CARRADORE, Monte Alegre ilha do sol (A. da Silva Ferreira), pp. 408-409; Francis DESRAMAUT, Don Bosco en son temps (1815-1888) (F. Motto), pp. 409-412; Alberto GARCÍA-VERDUGO e Cipriano SAN MILLAN, Desde el Arenal al Castro 100 años de Don Bosco en Vigo 1894-1994 (A. da Silva Ferreira), pp. -

Le Complicate Missioni Della Patagonia Da Don Bosco a Don Rua: Situazione Iniziale, Sviluppi, Bilancio*

NOTE LE COMPLICATE MISSIONI DELLA PATAGONIA DA DON BOSCO A DON RUA: SITUAZIONE INIZIALE, SVILUPPI, BILANCIO* Maria Andrea Nicoletti* Introduzione La Patagonia si è costituita come il primo territorio salesiano ad gentes su un duplice versante: su quello amministrativo, sulla base di impegni formali di fronte alle istituzioni civili ed ecclesiastiche (collegio Propaganda Fide, Santa Sede e gli Stati argentino e cileno); e su quello missionario ed educativo, mediante l’elaborazione di un piano di centri missionari in circuiti e reti, che hanno consolidato l’opera salesiana. Senza dubbio, l’attualizzazione del pro getto ha percorso diverse vie: da una parte appunto i rapporti con la Santa Sede e con gli Stati argentino e cileno, che hanno aperto un percorso com plesso e traumatico sull’amministrazione del Vicariato e la Prefettura aposto lica, e dall’altra l’elaborazione di modelli missionari che si sono adattati a una realtà patagonica in movimento, segnata dalla violenza dopo la conquista. Possiamo considerare il periodo di don Bosco come il ciclo di fonda zione per eccellenza, con un ideale ed un obiettivo preciso: la costituzione della Patagonia come territorio missionario, ma attraverso un’organizzazione che si faceva strada man mano che si procedeva. Il periodo di don Rua, segnò invece un ciclo d’ordine e di riorganizzazione dell’opera dei Salesiani, “sparsi ormai su tutta la faccia della terra”1, con il mantenerla però nella “fedeltà a don Bosco”2, con il “far rifiorire lo spirito di Don Bosco tra di noi ed anche organizzare ed ordinare vie più le nostre Case”3. * Ringrazio il prof. -

The Salesian Translator's Prayer Dear Lord, Thank You for Entrusting Me

The Salesian Translator’s Prayer Dear Lord, thank you for entrusting me with a wonderful mission as a translator in the Salesian Family. Help me to understand what this article, this book is telling me – show me the true meaning and how to express it in my own language, so that it will help to build up the Church and give growth to the Salesian charism. 1 Table of Contents ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 Part 1................................................................................................................................................4 BEFORE – Workshop preparation....................................................................................................4 Rector Major’s Message.........................................................................................................5 General Councillor for East Asia-Oceania Region...................................................................7 Why are we here today?.....................................................................................................7 Institutional background of ‘Salesian translations’ in EAO region.......................................9 Translation process ‘5 points working scheme’.................................................................10 Formation of Salesian translators – way forward..............................................................12 Working conclusions – at province, region and -

Braido Pietro, Don Bosco Prete Dei Giovani Nel Secolo Delle Libertà. 1 Vol

ISTITUTO STORICO SALESIANO - ROMA STUDI - 20 Nella lieta occasione del 90º genetliaco del prof. Pietro Braido l’Istituto Storico Salesiano è lieto di offrire a studiosi, amici di don Bosco e membri della Famiglia salesiana la terza e definitiva edizione, rivista dall’autore, dell’Opera, Don Bosco, prete dei giovani, nel secolo delle libertà frutto di 50 anni di attente ricerche, punto di arrivo degli studi su don Bosco all’inizio del XXI secolo, punto di partenza per nuovi approfondimenti. La circostanza risulta particolarmente felice per la contemporanea apertura delle manifestazioni culturali del centenario della morte del 1º successore di don Bosco, don Michele Rua e l’imminente celebrazione ufficiale del 150º anniversario della nascita della società salesiana. All’autore il grazie più sincero e a tutti i migliori auguri per una feconda lettura. Don Francesco Motto, direttore dell’ISS colleghi ed amici Roma, 24 maggio 2009 ISTITUTO STORICO SALESIANO - ROMA STUDI - 20 PIETRO BRAIDO DON BOSCO PRETE DEI GIOVANI NEL SECOLO DELLE LIBERTÀ “Non il vero, ma il reale cioè il vero con la sua storicità, con la sua concretezza nel divenire, nel tempo” (Ch. Péguy) “Mi raccomando ancora che non si dia gran retta ai sogni etc. Se questi aiutano l’intelligenza di cose morali, oppure delle nostre regole, va bene; si ritengano. Altrimenti non se ne faccia alcun pregio” (lett. a mons. Giovanni Cagliero, 10 febbr. 1885, E IV 314) VOLUME PRIMO Terza edizione corretta e ritoccata LAS - ROMA Nel ricordo degli insigni Maestri Valentino Panzarasa e Franc Walland © 2009 by LAS - Libreria Ateneo Salesiano Piazza dell’Ateneo Salesiano, 1 - 00139 ROMA Tel.