Crime Scene Investigation Through Textual Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Customizable • Ease of Access Cost Effective • Large Film Library

CUSTOMIZABLE • EASE OF ACCESS COST EFFECTIVE • LARGE FILM LIBRARY www.criterionondemand.com Criterion-on-Demand is the ONLY customizable on-line Feature Film Solution focused specifically on the Post Secondary Market. LARGE FILM LIBRARY Numerous Titles are Available Multiple Genres for Educational from Studios including: and Research purposes: • 20th Century Fox • Foreign Language • Warner Brothers • Literary Adaptations • Paramount Pictures • Justice • Alliance Films • Classics • Dreamworks • Environmental Titles • Mongrel Media • Social Issues • Lionsgate Films • Animation Studies • Maple Pictures • Academy Award Winners, • Paramount Vantage etc. • Fox Searchlight and many more... KEY FEATURES • 1,000’s of Titles in Multiple Languages • Unlimited 24-7 Access with No Hidden Fees • MARC Records Compatible • Available to Store and Access Third Party Content • Single Sign-on • Same Language Sub-Titles • Supports Distance Learning • Features Both “Current” and “Hard-to-Find” Titles • “Easy-to-Use” Search Engine • Download or Streaming Capabilities CUSTOMIZATION • Criterion Pictures has the rights to over 15000 titles • Criterion-on-Demand Updates Titles Quarterly • Criterion-on-Demand is customizable. If a title is missing, Criterion will add it to the platform providing the rights are available. Requested titles will be added within 2-6 weeks of the request. For more information contact Suzanne Hitchon at 1-800-565-1996 or via email at [email protected] LARGE FILM LIBRARY A Small Sample of titles Available: Avatar 127 Hours 2009 • 150 min • Color • 20th Century Fox 2010 • 93 min • Color • 20th Century Fox Director: James Cameron Director: Danny Boyle Cast: Sam Worthington, Sigourney Weaver, Cast: James Franco, Amber Tamblyn, Kate Mara, Michelle Rodriguez, Zoe Saldana, Giovanni Ribisi, Clemence Poesy, Kate Burton, Lizzy Caplan CCH Pounder, Laz Alonso, Joel Moore, 127 HOURS is the new film from Danny Boyle, Wes Studi, Stephen Lang the Academy Award winning director of last Avatar is the story of an ex-Marine who finds year’s Best Picture, SLUMDOG MILLIONAIRE. -

Game Over», L’Innocenza Quecento a Palazzo Vecchio - È Diventato Un Caso Giudiziario

GIOVEDÌ 8 DICEMBRE 2011 il manifesto pagina 13 VISIONI DACIA MARAINI ANDREA SEGRE Sono aperte le iscrizioni alla scuola di drammaturgia abruzzese diretta da Dacia Maraini, che il Nonostante le poche copie in distribuzione, al regista è stato consegnato il premio Fac alle 16 dicembre terrà la prima lezione assieme alla regista Emma Dante. Nata dall’Associazione Giornate Professionali di Cinema a Sorrento, per il film «Io sono li», e anche l’Asti Film Festival Teatro di Gioia, la scuola intende formare dei professionisti nel campo teatrale, dalla regia lo premia come miglior film. Per lanciare il nuovo film «Io voglio vedere», Segre chiede agli all’arte della clownerie. Le lezioni si terranno fino ad agosto, in diverse località abruzzesi. spettatori di compilare un modulo per fare pressione su esercenti e sale cinematografiche. SULMONACINEMA 29 · Vince «L’estate di Giacomo» di Alessandro Comodin ARTE · Leonardo diventa un caso giudiziario La ricerca della «Battaglia di Anghiari» - c’è una sonda che sta «lavorando» da diver- si giorni in una intercapedine di muro, dietro il dipinto del Vasari, nella Sala dei Cin- «Game over», l’innocenza quecento a Palazzo Vecchio - è diventato un caso giudiziario. Dopo l’esposto da parte di Italia Nostra, redatto insieme a un gruppo di intellettuali e studiosi (non solo italiani), la procura di Firenze ha aperto un fascicolo e avviato un’indagine. L’accusa è quella di aver danneggiato l’affresco vasariano (la «Battaglia di Scanna- selvaggia delle immagini gallo») con un procedimento considerato «avventato»: lo staff dell'ingegner Maurizio Seracini, dell'università di San Diego, avrebbe infatti introdotto la microcamera nel- l’opera stessa del pittore, per tentare di scovare il capolavoro del Leonardo perduto da secoli. -

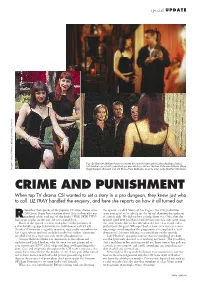

CSI Wanted to Set a Story in a Pro Dungeon, They Knew Just Who to Call

special UPDATE Top: Gil Grissom (William Petersen) masks his interest from Lady Heather (Melinda Clarke). Left: Melinda on set with consultant pro dom Mistress Juliana. Bottom: Catherine Willows (Marg Images courtesy of Alliance Atlantis Communications Inc Helgenberger), Grissom and Jim Brass (Paul Guilfoyle) about to enter Lady Heather’s Dominion CRIME AND PUNISHMENT When top TV drama CSI wanted to set a story in a pro dungeon, they knew just who to call. LIZ TRAY handled the enquiry, and here she reports on how it all turned out emember that episode of the popular TV crime drama series the episode – called Slaves of Las Vegas – the CSI production CSI:Crime Scene Investigation about the pro dom who was team contacted us for advice on the typical demographic make-up Rmurdered while working ‘off the books’? Well, SKIN TWO of a fetish club. We did our best to help them out. Only after the had a part to play in the way the story panned out. episode aired here (in March) did we discover that they were using Much of the episode’s action took place on the premises of the term ‘fetish club’ to describe what the rest of us would call a a wonderfully equipped domination establishment called Lady professional dungeon. Whoops! Such a basic error was even more Heather’s Dominion – a gothic mansion, supposedly somewhere in surprising considering that the programme also employed a “real Las Vegas, whose facilities included a fabulous sunken ‘classroom’ dominatrix”, Mistress Juliana, as a consultant on the episode. presided over by a Lucy Liu-style oriental headmistress. -

Feminist Aliens, Black Vampires, and Gay Witches: Creating a Critical

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2013 Feminist Aliens, Black Vampires, and Gay Witches: Creating a Critical Polis using SF Television in the College Composition Classroom Dawn Eyestone Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Educational Methods Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Eyestone, Dawn, "Feminist Aliens, Black Vampires, and Gay Witches: Creating a Critical Polis using SF Television in the College Composition Classroom" (2013). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 13037. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/13037 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Feminist aliens, black vampires, and gay witches: Creating a critical polis using SF television in the college composition classroom by Dawn Eyestone A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: English (Rhetoric and Professional Communication) Program of Study Committee: Barbara Blakely, Major Professor Greg Wilson Gloria Betcher Abby Dubisar Joel Geske -

“Things Fall Apart” Guest: Jennifer Palmieri

The West Wing Weekly 6.21: “Things Fall Apart” Guest: Jennifer Palmieri [Intro Music] HRISHI: You’re listening to the West Wing Weekly. I’m Hrishikesh Hirway. JOSH: And I’m Joshua Malina. HRISHI: Today we’re talking about episode 21 from season 6, it’s called “Things Fall Apart.” JOSH: This episode was written by Peter Noah and directed by Nelson McCormick. It first aired on March 30th 2005. HRISHI: I don’t believe we’ve heard the name Nelson McCormick before. Is that someone whose directed The West Wing before? JOSH: No, I think not. This is his first of what will turn out to be two episodes of The West Wing. He also directed an episode called “Transition.” Which we’ll get to. Oh we’ll get to it. HRISHI: Joining us later on this episode Jennifer Palmieri, Communications Director for the Hillary Clinton campaign and formerly for the Obama White House. JOSH: What do you think of this one? HRISHI: I, I like the plot of this episode. I think it’s interesting what happens with the convention and the nomination process, but the execution of it, I have issues with here and there. Really just a few moments here and there in the writing. JOSH: I think we will find ourselves in accord as I wrote down ‘Great bones, not enough meat’ HRISHI: Hey look at that. Yeah. That’s a good way of putting it. And before we jump into our discussion, here’s a synopsis from Warner Brothers. “The success of the impeccably organized Republican convention contrasts with the Democrats who look in disarray as the candidates continue to battle to be the Democratic Party Presidential nominee. -

Seminole-Tribune-July-30-2010.Pdf

Disc Golf Native Learning Center’s July 4 Celebrations Pool Party Summer Conference COMMUNITY v 8A and 9A SPORTS v 2C EDUCATION v 3B 7PMVNF999*t/VNCFS +VMZ Tribal Council Youth Conference in Orlando Teaches Children Vital Life Lessons Approves August BY CHRIS C. JENKINS *LUOV&OXE&RXQVHORUDQGFRQIHUHQFHFRRUJDQL]HU Staff Reporter ³7KLVZHHNLVDQH[DPSOHRIKRZZHWDNHWLPHRXWIRU our youth; they are our future. Spend time with them; Special Election ORLANDO ² 7KH DQQXDO +ROO\ZRRG 1RQ LWLVWKH,QGLDQZD\´ BY CHRIS C. JENKINS 5HVLGHQW)RUW3LHUFHDQG7UDLO6HPLQROH<RXWK&RQ- $V SHUHQQLDO JXHVW OHFWXUHUV IRU WKH FRQIHUHQFH Staff Reporter IHUHQFHEURXJKW\RXWKDQGWKHLUSDUHQWVWRJHWKHURQFH 9LOODORERVDQG(QJOLVKVDLGLQVWLOOLQJ1DWLYHSULGHDQG again with the goal of enlightening its future leaders in DUWLVWLFH[SUHVVLRQFRQWLQXHVWREHWKHLUPDLQPHVVDJH BIG CYPRESS — 7ULEDO&RXQFLOFRQ- WKHDUHDVRIFXOWXUHGUXJSUHYHQWLRQ¿QDQFHVHGXFD- HDFK\HDU YHQHGRQWKH%LJ&\SUHVV5HVHUYDWLRQ&RP- WLRQDUWKHDOWKDQGRWKHUHVVHQWLDOOLIHVW\OHWRSLFV ³,ZDQWWKHPWREHSURXGWREH,QGLDQ:KDWHYHULW PXQLW\&HQWHU-XO\DQGDQGDXWKRUL]HG 7KHFRPI\*D\ORUG3DOPV5HVRUWDQG&RQYHQWLRQ LVWKH\DUHWU\LQJWROHDUQLWZLOOKHOSWKHPWRNHHSWKHLU DVSHFLDOHOHFWLRQIRUWKH%LJ&\SUHVV7ULEDO &HQWHUVHUYHGDVKRPHEDVHWRGR]HQVZLWKWKH KHDGVKHOGKLJK´9LOODORERVVDLG³7KHUHDUHQRWDORW &RXQFLO5HSUHVHQWDWLYHVHDW WKHPHRI³3URVSHULW\7KURXJK3HUVHYHUDQFH´-XO\ RI1DWLYHUROHPRGHOVWRORRNXSWR:HKDYHWRVHWWKDW 7KH VSHFLDO HOHFWLRQ ZLOO WDNH SODFH 6HYHUDO JXHVWV DQG SUHVHQWHUV ZHUH IHDWXUHG H[DPSOH´ IURPDPWRSP$XJXVWDWWKH6H- WKURXJKRXWWKHZHHNLQFOXGLQJ7LIIDQ\6LQFODLUUHLJQ- ³,WLVDERXWLQVSLULQJ\RXQJSHRSOHWREHFUHDWLYH´ -

Tom Hanks Halle Berry Martin Sheen Brad Pitt Robert Deniro Jodie Foster Will Smith Jay Leno Jared Leto Eli Roth Tom Cruise Steven Spielberg

TOM HANKS HALLE BERRY MARTIN SHEEN BRAD PITT ROBERT DENIRO JODIE FOSTER WILL SMITH JAY LENO JARED LETO ELI ROTH TOM CRUISE STEVEN SPIELBERG MICHAEL CAINE JENNIFER ANISTON MORGAN FREEMAN SAMUEL L. JACKSON KATE BECKINSALE JAMES FRANCO LARRY KING LEONARDO DICAPRIO JOHN HURT FLEA DEMI MOORE OLIVER STONE CARY GRANT JUDE LAW SANDRA BULLOCK KEANU REEVES OPRAH WINFREY MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY CARRIE FISHER ADAM WEST MELISSA LEO JOHN WAYNE ROSE BYRNE BETTY WHITE WOODY ALLEN HARRISON FORD KIEFER SUTHERLAND MARION COTILLARD KIRSTEN DUNST STEVE BUSCEMI ELIJAH WOOD RESSE WITHERSPOON MICKEY ROURKE AUDREY HEPBURN STEVE CARELL AL PACINO JIM CARREY SHARON STONE MEL GIBSON 2017-18 CATALOG SAM NEILL CHRIS HEMSWORTH MICHAEL SHANNON KIRK DOUGLAS ICE-T RENEE ZELLWEGER ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER TOM HANKS HALLE BERRY MARTIN SHEEN BRAD PITT ROBERT DENIRO JODIE FOSTER WILL SMITH JAY LENO JARED LETO ELI ROTH TOM CRUISE STEVEN SPIELBERG CONTENTS 2 INDEPENDENT | FOREIGN | ARTHOUSE 23 HORROR | SLASHER | THRILLER 38 FACTUAL | HISTORICAL 44 NATURE | SUPERNATURAL MICHAEL CAINE JENNIFER ANISTON MORGAN FREEMAN 45 WESTERNS SAMUEL L. JACKSON KATE BECKINSALE JAMES FRANCO 48 20TH CENTURY TELEVISION LARRY KING LEONARDO DICAPRIO JOHN HURT FLEA 54 SCI-FI | FANTASY | SPACE DEMI MOORE OLIVER STONE CARY GRANT JUDE LAW 57 POLITICS | ESPIONAGE | WAR SANDRA BULLOCK KEANU REEVES OPRAH WINFREY MATTHEW MCCONAUGHEY CARRIE FISHER ADAM WEST 60 ART | CULTURE | CELEBRITY MELISSA LEO JOHN WAYNE ROSE BYRNE BETTY WHITE 64 ANIMATION | FAMILY WOODY ALLEN HARRISON FORD KIEFER SUTHERLAND 78 CRIME | DETECTIVE -

“DOA for a Day”

“DOA for a Day” Episode #415 Written By John Dove & Peter M. Lenkov DIR: Christine Moore © MMVIII SHOOTING SCRIPT 2/29/08 CBS Broadcasting Inc. and Entertainment AB Funding LLC All Rights Reserved No portion of this material may be copied or distributed without the prior consent of CBS Broadcasting, Inc. Ep. #415 – “DOA for a Day” Shooting Script – 2/29/08 “DOA for a Day” Ep. #415 CASTU LIST MAC TAYLOR STELLA BONASERA DANNY MESSER DR. SHELDON HAWKES DET. DON FLACK LINDSAY MONROE DET. JESSICA ANGELL ADAM ROSS DR. SID HAMMERBACK SUSPECT X RUSS MCHENRY (War hero and son of one of Suspect X’s previous vics, Judge McHenry) JORDAN GATES (the Mayor’s Criminal Justice Coordinator Mac’s helped before; Kelly’s boss) BARTENDER (At Club Random, the Cosplay club) TAYLOR AVATAR (Is killed by Suspect X’s Avatar at the club) SUSPECT X AVATAR (Let’s our team know she’s watching) FeaturedU Characters (non-speaking only) Male (V.O. only) (NY Crime Catchers) Unis Kelly Mann (Vic made to look like Suspect X; Jordan Gates’ assistant) ND Techs M.E. Techs Detectives Mayor’s Protection Detail Sound Techs Club Random Patrons Dr. Joseph Kirkbaum (made Kelly Mann look like Suspect X as payback to her but then became her vic as well) ESU Officers Sergeants Williams and Clark (on teleconference) FBI Special Agents Steve Beck and Kevin Halinan (on teleconference) ND Woman (Disguised as Suspect X sent in by her to make sure it’s not a trap) Uniformed Officer ESU Officers Pedestrians Ep. #415 – “DOA for a Day” Shooting Script – 2/29/08 “DOA for a Day” Ep. -

Global Upfront New and Returning Series

GLOBAL ANNOUNCES STAR-STUDDED 2021/22 PRIMETIME LINEUP FILLED WITH THE MOST IN-DEMAND NEW PICK- UPS AND RETURNING HIT BLOCKBUSTERS New Global Original Family Law and Franchise Expansions CSI: Vegas, NCIS: Hawai’i, and FBI: International Lead Global’s Fall Schedule The Highly-Anticipated Return of Survivor Joins New Seasons of Hits The Equalizer, Tough As Nails, New Amsterdam, and More New Comedy Ghosts and Audience Favourite United States of Al Bring the Laughs to Global This Fall Stream Anytime with STACKTV or the Global TV App Additional photography and press kit material can be found here. Follow us on Twitter at @GlobalTV_PR To share this release: https://bit.ly/3w3lm3x #CorusUpfront For Immediate Release TORONTO, June 8, 2021 – Ahead of the #CorusUpfront on June 9, Global unveils its 2021/22 programming lineup loaded with exciting series pick-ups and returning established hits. Global’s fall offering promises to deliver a dynamic and diverse schedule filled with thrilling dramas, hilarious comedies, captivating reality television, and much more. Adding 10 new series, including five new primetime series debuting this fall, Global’s schedule features 18 hours of simulcast with four out of seven days entirely simulcast in primetime. Corus’ conventional network offers Canadians a full suite of options for TV lovers looking to stream its blockbuster franchises and hottest new shows in every genre, anytime they want on STACKTV and the Global TV App. “After an unprecedented year, Global is back in full force this fall with a jam-packed schedule of prestigious dramas, powerhouse franchises, and laugh-out-loud comedies,” said Troy Reeb, Executive Vice President, Broadcast Networks, Corus Entertainment. -

Newsletter 15/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 15/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 212 - September 2007 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 15/07 (Nr. 212) September 2007 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, schen und japanischen DVDs Aus- Nach den in diesem Jahr bereits liebe Filmfreunde! schau halten, dann dürfen Sie sich absolvierten Filmfestivals Es gibt Tage, da wünscht man sich, schon auf die Ausgaben 213 und ”Widescreen Weekend” (Bradford), mit mindestens fünf Armen und 214 freuen. Diese werden wir so ”Bollywood and Beyond” (Stutt- mehr als nur zwei Hirnhälften ge- bald wie möglich publizieren. Lei- gart) und ”Fantasy Filmfest” (Stutt- boren zu sein. Denn das würde die der erfordert das Einpflegen neuer gart) steht am ersten Oktober- tägliche Arbeit sicherlich wesent- Titel in unsere Datenbank gerade wochenende das vierte Highlight lich einfacher machen. Als enthu- bei deutschen DVDs sehr viel mehr am Festivalhimmel an. Nunmehr siastischer Filmfanatiker vermutet Zeit als bei Übersee-Releases. Und bereits zum dritten Mal lädt die man natürlich schon lange, dass Sie können sich kaum vorstellen, Schauburg in Karlsruhe zum irgendwo auf der Welt in einem was sich seit Beginn unserer Som- ”Todd-AO Filmfestival” in die ba- kleinen, total unauffälligen Labor merpause alles angesammelt hat! dische Hauptstadt ein. Das diesjäh- inmitten einer Wüstenlandschaft Man merkt deutlich, dass wir uns rige Programm wurde gerade eben bereits mit genmanipulierten Men- bereits auf das Herbst- und Winter- offiziell verkündet und das wollen schen experimentiert wird, die ge- geschäft zubewegen. -

Sydney Program Guide

3/20/2020 prtten04.networkten.com.au:7778/pls/DWHPROD/Program_Reports.Dsp_ONE_Guide?psStartDate=22-Mar-20&psEndDate=04-Apr… SYDNEY PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 22nd March 2020 06:00 am Home Shopping (Rpt) Home Shopping 06:30 am Home Shopping (Rpt) Home Shopping 07:00 am Home Shopping (Rpt) Home Shopping 07:30 am Key Of David PG The Key of David, a religious program, covers important issues of today with a unique perspective. 08:00 am Star Trek: Voyager (Rpt) PG Workforce, Part 1 Mild Violence, Mature Themes The Voyager crew's memories are wiped by a society and made to work among their population. Starring: Kate Mulgrew, Jeri Ryan, Robert Beltran, Robert Picardo, Tim Russ, Roxann Dawson, Ethan Phillips, Robert Duncan McNeill, Garrett Wang Guest Starring: James Read, Robert Joy, Don Most, John Aniston 09:00 am Star Trek: Voyager (Rpt) PG Workforce, Part 2 Violence, Mature Themes Chakotay desperately tries to jog the memories of Janeway and the rest of the crew, but is it too late? Starring: Kate Mulgrew, Jeri Ryan, Robert Beltran, Robert Picardo, Tim Russ, Roxann Dawson, Ethan Phillips, Robert Duncan McNeill, Garrett Wang Guest Starring: James Read, Don Most, Robert Joy, Jay Harrington, John Aniston 10:00 am Shark Tank (Rpt) CC PG Has 24-year old Jade found a gap in the beauty market? Can a Queenland entrepreneur entice the Shark's into his invention? Can an online mattress business secure a half a million dollar investment? 11:00 am Escape Fishing With ET (Rpt) CC G Escape with Andrew Ettingshausen as he travels Australia and the Pacific, hunting out the most exciting species, the most interesting spots and the most fun mates to go fishing with. -

8 TV Power Games: Friends and Law & Order

8 TV Power Games: Friends and Law & Order There is no such thing as a one-man show | at least not in television: one feature that all TV shows have in common is the combination of a large number of diverse contributors: producers, scriptwriters, actors, and so on. This is illustrated in Exhibit 8.1, which depicts the links between key contributors to the making and selling of a TV show. Solid lines repre- sent some form of contractual relationship, whereas dashed lines represent non-contractual relationships of relevance for value creation and value distribution. As is the case with movies, pharmaceutical drugs, and other products, the distribution of TV show values is very skewed: many TV shows are worth relatively little, whereas a few shows generate a very high value: For example, at its peak Emmy Award-winning drama ER fetched $13 million per episode.1 How does the value created by successful shows get divided among its various contrib- utors, in particular actors, producers and networks? Who gets the biggest slice of the big pie? In this chapter, I address this question by looking at two opposite extreme cases in terms of relative negotiation power: Law & Order and Friends. Law & Order | and profits The legal drama series Law & Order was first broadcast on NBC on September 13, 1990. (The pilot episode, produced in 1988, was intended for CBS, but the network rejected it, just as Fox did later, in both cases because the show did not feature any \breakout" characters.) By the time the last show aired on May 24, 2010, it was the longest-running crime drama on American prime time TV.