Stemming the Tide: the Presentation of Women Scientists in CSI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Customizable • Ease of Access Cost Effective • Large Film Library

CUSTOMIZABLE • EASE OF ACCESS COST EFFECTIVE • LARGE FILM LIBRARY www.criterionondemand.com Criterion-on-Demand is the ONLY customizable on-line Feature Film Solution focused specifically on the Post Secondary Market. LARGE FILM LIBRARY Numerous Titles are Available Multiple Genres for Educational from Studios including: and Research purposes: • 20th Century Fox • Foreign Language • Warner Brothers • Literary Adaptations • Paramount Pictures • Justice • Alliance Films • Classics • Dreamworks • Environmental Titles • Mongrel Media • Social Issues • Lionsgate Films • Animation Studies • Maple Pictures • Academy Award Winners, • Paramount Vantage etc. • Fox Searchlight and many more... KEY FEATURES • 1,000’s of Titles in Multiple Languages • Unlimited 24-7 Access with No Hidden Fees • MARC Records Compatible • Available to Store and Access Third Party Content • Single Sign-on • Same Language Sub-Titles • Supports Distance Learning • Features Both “Current” and “Hard-to-Find” Titles • “Easy-to-Use” Search Engine • Download or Streaming Capabilities CUSTOMIZATION • Criterion Pictures has the rights to over 15000 titles • Criterion-on-Demand Updates Titles Quarterly • Criterion-on-Demand is customizable. If a title is missing, Criterion will add it to the platform providing the rights are available. Requested titles will be added within 2-6 weeks of the request. For more information contact Suzanne Hitchon at 1-800-565-1996 or via email at [email protected] LARGE FILM LIBRARY A Small Sample of titles Available: Avatar 127 Hours 2009 • 150 min • Color • 20th Century Fox 2010 • 93 min • Color • 20th Century Fox Director: James Cameron Director: Danny Boyle Cast: Sam Worthington, Sigourney Weaver, Cast: James Franco, Amber Tamblyn, Kate Mara, Michelle Rodriguez, Zoe Saldana, Giovanni Ribisi, Clemence Poesy, Kate Burton, Lizzy Caplan CCH Pounder, Laz Alonso, Joel Moore, 127 HOURS is the new film from Danny Boyle, Wes Studi, Stephen Lang the Academy Award winning director of last Avatar is the story of an ex-Marine who finds year’s Best Picture, SLUMDOG MILLIONAIRE. -

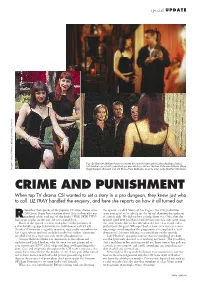

CSI Wanted to Set a Story in a Pro Dungeon, They Knew Just Who to Call

special UPDATE Top: Gil Grissom (William Petersen) masks his interest from Lady Heather (Melinda Clarke). Left: Melinda on set with consultant pro dom Mistress Juliana. Bottom: Catherine Willows (Marg Images courtesy of Alliance Atlantis Communications Inc Helgenberger), Grissom and Jim Brass (Paul Guilfoyle) about to enter Lady Heather’s Dominion CRIME AND PUNISHMENT When top TV drama CSI wanted to set a story in a pro dungeon, they knew just who to call. LIZ TRAY handled the enquiry, and here she reports on how it all turned out emember that episode of the popular TV crime drama series the episode – called Slaves of Las Vegas – the CSI production CSI:Crime Scene Investigation about the pro dom who was team contacted us for advice on the typical demographic make-up Rmurdered while working ‘off the books’? Well, SKIN TWO of a fetish club. We did our best to help them out. Only after the had a part to play in the way the story panned out. episode aired here (in March) did we discover that they were using Much of the episode’s action took place on the premises of the term ‘fetish club’ to describe what the rest of us would call a a wonderfully equipped domination establishment called Lady professional dungeon. Whoops! Such a basic error was even more Heather’s Dominion – a gothic mansion, supposedly somewhere in surprising considering that the programme also employed a “real Las Vegas, whose facilities included a fabulous sunken ‘classroom’ dominatrix”, Mistress Juliana, as a consultant on the episode. presided over by a Lucy Liu-style oriental headmistress. -

Feminist Aliens, Black Vampires, and Gay Witches: Creating a Critical

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2013 Feminist Aliens, Black Vampires, and Gay Witches: Creating a Critical Polis using SF Television in the College Composition Classroom Dawn Eyestone Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Educational Methods Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Eyestone, Dawn, "Feminist Aliens, Black Vampires, and Gay Witches: Creating a Critical Polis using SF Television in the College Composition Classroom" (2013). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 13037. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/13037 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Feminist aliens, black vampires, and gay witches: Creating a critical polis using SF television in the college composition classroom by Dawn Eyestone A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: English (Rhetoric and Professional Communication) Program of Study Committee: Barbara Blakely, Major Professor Greg Wilson Gloria Betcher Abby Dubisar Joel Geske -

“Things Fall Apart” Guest: Jennifer Palmieri

The West Wing Weekly 6.21: “Things Fall Apart” Guest: Jennifer Palmieri [Intro Music] HRISHI: You’re listening to the West Wing Weekly. I’m Hrishikesh Hirway. JOSH: And I’m Joshua Malina. HRISHI: Today we’re talking about episode 21 from season 6, it’s called “Things Fall Apart.” JOSH: This episode was written by Peter Noah and directed by Nelson McCormick. It first aired on March 30th 2005. HRISHI: I don’t believe we’ve heard the name Nelson McCormick before. Is that someone whose directed The West Wing before? JOSH: No, I think not. This is his first of what will turn out to be two episodes of The West Wing. He also directed an episode called “Transition.” Which we’ll get to. Oh we’ll get to it. HRISHI: Joining us later on this episode Jennifer Palmieri, Communications Director for the Hillary Clinton campaign and formerly for the Obama White House. JOSH: What do you think of this one? HRISHI: I, I like the plot of this episode. I think it’s interesting what happens with the convention and the nomination process, but the execution of it, I have issues with here and there. Really just a few moments here and there in the writing. JOSH: I think we will find ourselves in accord as I wrote down ‘Great bones, not enough meat’ HRISHI: Hey look at that. Yeah. That’s a good way of putting it. And before we jump into our discussion, here’s a synopsis from Warner Brothers. “The success of the impeccably organized Republican convention contrasts with the Democrats who look in disarray as the candidates continue to battle to be the Democratic Party Presidential nominee. -

Global Upfront New and Returning Series

GLOBAL ANNOUNCES STAR-STUDDED 2021/22 PRIMETIME LINEUP FILLED WITH THE MOST IN-DEMAND NEW PICK- UPS AND RETURNING HIT BLOCKBUSTERS New Global Original Family Law and Franchise Expansions CSI: Vegas, NCIS: Hawai’i, and FBI: International Lead Global’s Fall Schedule The Highly-Anticipated Return of Survivor Joins New Seasons of Hits The Equalizer, Tough As Nails, New Amsterdam, and More New Comedy Ghosts and Audience Favourite United States of Al Bring the Laughs to Global This Fall Stream Anytime with STACKTV or the Global TV App Additional photography and press kit material can be found here. Follow us on Twitter at @GlobalTV_PR To share this release: https://bit.ly/3w3lm3x #CorusUpfront For Immediate Release TORONTO, June 8, 2021 – Ahead of the #CorusUpfront on June 9, Global unveils its 2021/22 programming lineup loaded with exciting series pick-ups and returning established hits. Global’s fall offering promises to deliver a dynamic and diverse schedule filled with thrilling dramas, hilarious comedies, captivating reality television, and much more. Adding 10 new series, including five new primetime series debuting this fall, Global’s schedule features 18 hours of simulcast with four out of seven days entirely simulcast in primetime. Corus’ conventional network offers Canadians a full suite of options for TV lovers looking to stream its blockbuster franchises and hottest new shows in every genre, anytime they want on STACKTV and the Global TV App. “After an unprecedented year, Global is back in full force this fall with a jam-packed schedule of prestigious dramas, powerhouse franchises, and laugh-out-loud comedies,” said Troy Reeb, Executive Vice President, Broadcast Networks, Corus Entertainment. -

Let's Get Physical

Small-ScreenThe SensationsInside: Pg. 15 TARGET SEES DOUBLE/3 MORE CHINA QUOTAS/16 WWD WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • TheTHURSDAY Retailers’ Daily Newspaper • May 19, 2005• $2.00 List Sportswear Let’s Get Physical NEW YORK — Work it out. Designers are upping the style quotient this fall with activewear looks that cross function with lots of fashion. Stella McCartney’s first collection for Adidas was a knockout at retail, and here, from her second, Modal tanks with polyester pants and a cotton and polyester top with nylon and elastic leggings, both with Adidas Stella McCartney shoes. For more designer activewear looks, see pages 6 and 7. The Future of Fendi: T New Contract for Karl, Brand Eyes $1B in Sales By Miles Socha UMP; STYLED BY DANIELA GILBER UMP; STYLED BY Y/J ROME — Karl Lagerfeld eased into his gleaming white desk at Fendi’s new headquarters here Wednesday, picked up a pencil and, with a quick flourish, finished off what must be his zillionth ANK ARENDS; MAKEUP BY LUCK ANK ARENDS; MAKEUP BY sketch for the Roman house. “It’s a stunning building, no?” Lagerfeld quipped. Only minutes earlier, the designer sat at a press conference next to LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton chairman Bernard Arnault, who confirmed a WWD report that Lagerfeld had signed SA MOLSON/SUPREME; HAIR BY KENSHIN ASANO/FR SA MOLSON/SUPREME; HAIR BY another “long-term” contract with Fendi, See Lagerfeld, Page14 PHOTO BY ROBERT MITRA; MODELS: COLLEEN BAXTER AND MELIS ROBERT PHOTO BY WWD.COM WWDTHURSDAY Sportswear FASHION ™ A slew of designers are adding their names and talent to sport lines, adding 6 fashion to function from the slopes to the courts. -

Framing the Body, Staging the Gaze” Representations of the Body in Forensic Crime Fiction and Film (Ph.D

David Levente Palatinus “Framing the Body, Staging the Gaze” Representations of the Body in Forensic Crime Fiction and Film (Ph.D. Dissertation) Peter Pazmany Catholic University Faculty of Humanities Doctoral School of Literary Studies School Director: Prof. Éva Martonyi, CSc. university professor Theories of Literature and Culture Program Program Leader: Prof. Kornélia Horváth, Ph.D., lecturer, Institute of Literary Studies Dissertation Supervisor: Prof. Kornélia Horváth, Ph.D., lecturer, Institute of Literary Studies 2009 1 Palatinus Levente Dávid “A test bekeretezése, a tekintet színrevitele” A test reprezentációi a törvényszéki krimiben és filmben Doktori (Ph.D.) értekezés Pázmány Péter Katolikus Egyetem Bölcsészettudományi Kar Irodalomtudományi Doktori Iskola School Director: Prof. Éva Martonyi, CSc. egyetemi tanár Irodalom- és Kultúraelméleti M őhely Mőhelyvezet ı: Horváth Kronélia, Ph.D., docens, Irodalomtudományi Intézet Témavezet ı: Horváth Kornélia, Ph.D., docens, Irodalomtudományi Intézet 2009 2 Contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................5 1. Corporeality, Vision, Popular Culture: .................................................................................7 A Skeptical Introduction ............................................................................................................7 2. (Re-)Framing the Image ...................................................................................................17 2.1 T(h)e(rr)orizing -

“Tell-Tale Hearts”

“Tell - Tale Hearts ” Episode #1202 Story by Larry Mitchell Teleplay by Joe Pokaski Dir.: Brad Tanenbaum C S I: Crime Scene Investigation “Tell-Tale Hearts” Episode #1202 Story by Larry Mitchell Teleplay by Joe Pokaski Dir.: Brad Tanenbaum The persons and events portrayed in this film are fictitious. Any Shooting Script similarity to actual persons, living or dead, or any events is unintentional. August 1, 2011 ! MMXI CBS Broadcasting Inc. and Entertainment AB Funding LLC All Rights Reserved. CBS BROADCASTING INC. AND ENTERTAINMENT AB FUNDING LLC ARE THE AUTHORS OF THIS PROGRAM FOR THE PURPOSES OF COPYRIGHT AND OTHER LAWS. No portion of this material may be copied or distributed without the prior consent of CBS Broadcasting Inc. and Entertainment AB Funding LLC. 8/1/2011 “Tell-Tale Hearts” Episode #1202 CAST D.B. RUSSELL CATHERINE WILLOWS NICK STOKES CAPT. JIM BRASS SARA SIDLE GREG SANDERS DR. ROBBINS MORGAN BRODY DAVID HODGES DAVID PHILLIPS CONRAD ECKLIE OFFICER MITCHELL HENRY ANDREWS OFFICER METCALF OFFICER ANDI CANTELVO ALISON MATT JOHN LEE REPORTER #1 REPORTER #2 LESLIE GITIG XIOMARA GARCIA * LONNY GALLOWS MAURICE GALLOWS Featured, Non-Speaking N.D. Uniforms & Detectives N.D. CSIs & N.D. Coroner’s Assistant Anita Chambliss Susan Chambliss Cal Chambliss Fiona Chambliss Reporters and Cameramen Forest Green Lookiloos Construction Workers * REVISED 8/1/2011 “Tell-Tale Hearts” Episode #1202 SETS INTERIORS EXTERIORS CSI Las Vegas Skyline (Stock) Hallway Layout Room Forest Green Sustainable Community Ballistics Empty Street Evidence Locker -

AISNA Papers.Pdf

Il volume è pubblicato anche con il contributo del Centro Studi di Genere del Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici dell’Università di Trieste. Funding for this publication was provided in part by the Center for Gender Studies at the University of Trieste (Humanities Department). Cover Image: Francesco Pezzicar (1831-1890), L’emancipazione dei negri (“The Emancipation of the Negroes”), bronze sculpture 235 cm high, signed and dated F. Pezzicar 1873, purchased by the Trieste Civic Museum “Revoltella” in 1931. I testi pubblicati in questo volume sono liberamente disponibili su: / The texts included in this volume are available online at: http://www.openstarts.units.it/dspace/handle/10077/11293 impaginazione Verena Papagno © copyright Edizioni Università di Trieste, Trieste 2015. Proprietà letteraria riservata. I diritti di traduzione, memorizzazione elettronica, di riproduzione e di adattamento totale e parziale di questa pubblicazione, con qualsiasi mezzo (compresi i microfilm, le fotocopie e altro) sono riservati per tutti i paesi. ISBN 978-88-8303-689-7 (print) eISBN 978-88-8303-690-3 (online) EUT - Edizioni Università di Trieste Via E. Weiss, 21 – 34128 Trieste http://eut.units.it https://www.facebook.com/EUTEdizioniUniversitaTrieste Discourses of Emancipation and the Boundaries of Freedom Selected Papers from the 22nd AISNA Biennial International Conference Edited by Leonardo Buonomo and Elisabetta Vezzosi with the collaboration of Gabrielle Barfoot and Giulia Iannuzzi EUT EDIZIONI UNIVERSITÀ DI TRIESTE Contents 7 Acknowledgments Elisabetta Marino 79 The Italian American Family Leonardo Buonomo between Past and Present: The Elisabetta Vezzosi Place I Call Home (2012) by Maria 9 Introduction Mazziotti Gillan, and Mystics in the Family (2013) by Maria Famà 1. -

Feminist Periodicals

The Un vers ty of W scons n System Feminist Periodicals A current listing of contents WOMEN'S STUDIES Volume 23, Numbers 1 & 2, Spring & Summer 2003 Published by Phyllis Holman Weisbard LIBRARIAN Women's Studies Librarian Feminist Periodicals A current listing of contents Volume 23, Numbers 1 & 2, Spring & Summer 2003 Periodical literature is the culling edge of women's scholarship, feminist theory, and much of women's culture. Feminist Periodicals: A Current Listing of Contents is pUblished by the Office of the University of Wisconsin System Women's Studies Librarian on a quarterly basis with the intent of increasing public awareness of feminist periodicals. It is our hope that Feminist Periodicals will serve several purposes: to keep the reader abreast of current topics in feminist literature; to increase readers' familiarity with a wide spectrum of feminist periodicals; and to provide the requisite bibliographic information should a reader wish to subscribe to a journal or to obtain a particular article at her library or through interlibrary loan. (Users will need to be aware of the limitations of the new copyright law with regard to photocopying of copyrighted materials.) Table of contents pages from current issues of major feminist journals are reproduced in each issue of Feminist Periodicals, preceded by a comprehensive annotated listing of all journals we have selected. As pUblication schedules vary enormously, not every periodical will have table of contents pages reproduced in each issue of FP. The annotated listing provides the following information on each journal: 1. Year of first pUblication. 2. Frequency of publication. 3. -

Routledge International Encyclopedia of Women Global Women’S Issues and Knowledge

Routledge International Encyclopedia of Women Global Women’s Issues and Knowledge Volume 1 Ability—Education: Globalization Editorial Board General Editors Cheris Kramarae Dale Spender University of Oregon University of Queensland United States Australia Topic Editors ARTS AND LITERATURE HEALTH, REPRODUCTION, RELIGION AND SPIRITUALITY Ailbhe Smyth AND SEXUALITY Sister Mary John Mananzan University College, Dublin Dianne Forte Saint Scholastica’s College, Ireland Boston Women’s Health Book Manila Collective Liz Ferrier United States University of Queensland SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Australia HISTORY AND PHILOSOPHY Leigh Star CULTURE AND COMMUNICATION OF FEMINISM University of California, Angharad Valdivia Maggie Humm San Diego University of Illinois University of East London United States United States England ECOLOGY AND THE ENVIRONMENT VIOLENCE AND PEACE HOUSEHOLDS AND FAMILIES Ingar Palmlund Evelyne Accad Joan Mencher Linköping University University of Illinois at Urbana- City University of New York Sweden Champaign United States ECONOMY AND DEVELOPMENT United States Cora V.Baldock POLITICS AND THE STATE Murdoch University Nira Yuval-Davis WOMEN’S STUDIES Australia University of Greenwich Caryn McTighe Musil EDUCATION England American Association of Gill Kirkup Shirin M.Rai Colleges and Universities, Open University University of Warwick Washington, D.C. England England United States Honorary Editorial Advisory Board Nirmala Banerjee Phyllis Hall Beth Stafford Charlotte Bunch Jenny Kien Chizuko Ueno Hilda Ching Theresia Sauter-Bailliet Gaby Weiner Routledge International Encyclopedia of Women Global Women’s Issues and Knowledge Volume 1 Ability—Education: Globalization Cheris Kramarae and Dale Spender General Editors Routledge New York • London NOTICE Some articles in the Routledge International Encyclopedia of Women relate to physical and mental health; nothing in these articles, singly or collectively, is meant to replace the advice and expertise of physicians and other health professionals. -

CSI and Forensic Realism

CSI and Forensic Realism By Sarah Keturah Deutsch University of Wisconsin Law School Gray Cavender Arizona State University School of Justice & Social Inquiry CSI has consistently been among the top rated television programs since its debut in 2000. What is the secret to its popularity? Our analysis reveals that CSI combines the traditions of television's crime genre, especially the police procedural, with a creative sense of forensic realism. CSI constructs the illusion of science through its strategic web of forensic facticity. Ironically, although CSI depicts unrealistic crimes in a melodramatic fashion, this crime drama does so in a manner that suggests that its science is valid, that the audience understands science and can use it to solve crimes. Keywords: forensic facticity; TV crime genre; police procedural INTRODUCTION CSI: Crime Scene Investigation (CSI) has enjoyed an enviable status in television. Having completed its eighth season, a longevity that is rare in prime time television, this crime drama consistently has been the top rated program in its time slot both in its first run and rerun incarnations (see Nielsen Ratings, June 20-26, 2005; Toff, 7 April 2007: A16). Not only has CSI generated two successful spin-off series (CSI: Miami and CSI: NY), it has pushed forensic science terms and concepts into the popular discourse. Accompanying this diffusion has been the sense that science and the police are virtually infallible. Crime genre programs have been a staple since television's inception. The success of programs from Dragnet to NYPD Blue has evidenced the audience's fascination with crime dramas. In one sense, CSI has been another program in a long line of television crime dramas, and it has exhibited features common to the genre, for example, plots that were driven by violent crimes and the search for the criminal.