CSI and Forensic Realism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CSI Wanted to Set a Story in a Pro Dungeon, They Knew Just Who to Call

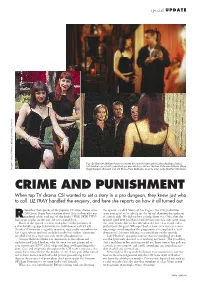

special UPDATE Top: Gil Grissom (William Petersen) masks his interest from Lady Heather (Melinda Clarke). Left: Melinda on set with consultant pro dom Mistress Juliana. Bottom: Catherine Willows (Marg Images courtesy of Alliance Atlantis Communications Inc Helgenberger), Grissom and Jim Brass (Paul Guilfoyle) about to enter Lady Heather’s Dominion CRIME AND PUNISHMENT When top TV drama CSI wanted to set a story in a pro dungeon, they knew just who to call. LIZ TRAY handled the enquiry, and here she reports on how it all turned out emember that episode of the popular TV crime drama series the episode – called Slaves of Las Vegas – the CSI production CSI:Crime Scene Investigation about the pro dom who was team contacted us for advice on the typical demographic make-up Rmurdered while working ‘off the books’? Well, SKIN TWO of a fetish club. We did our best to help them out. Only after the had a part to play in the way the story panned out. episode aired here (in March) did we discover that they were using Much of the episode’s action took place on the premises of the term ‘fetish club’ to describe what the rest of us would call a a wonderfully equipped domination establishment called Lady professional dungeon. Whoops! Such a basic error was even more Heather’s Dominion – a gothic mansion, supposedly somewhere in surprising considering that the programme also employed a “real Las Vegas, whose facilities included a fabulous sunken ‘classroom’ dominatrix”, Mistress Juliana, as a consultant on the episode. presided over by a Lucy Liu-style oriental headmistress. -

Stemming the Tide: the Presentation of Women Scientists in CSI

http://genderandset.open.ac.uk Stemming the Tide: The Presentation of Women Scientists in CSI Shane Warren1, Mark Goodman1, Rebecca Horton1, Nate Bynum2 1Mississippi State University, 2University of Nevada Las Vegas, USA ABSTRACT This paper evaluates the role of Sara Sidle played by Jorja Fox in CSI: Crime Scene Investigation (CSI) for 15 years, and her female co-stars, allowing us to discuss specific rewards and punishments (Fiske, 1987) assigned over the course of many episodes. We reviewed three of the 15 years of CSI: Crime Scene Investigation to understand the media presentation of women scientists. We found that CSI did present stereotypical views of the female investigators and that the female characters playing these roles were often punished by the script. However, we also found that the show provided an opportunity for the story of women to be told by these female characters. Accordingly, our examination of the character of Sara Sidle and the other forensic scientists found that the portrayal was more complex than previously literature suggests. KEYWORDS STEM; CSI; female scientists; media representation This journal uses Open Journal Systems 2.4.8.1, which is open source journal management and publishing software developed, supported, and freely distributed by the Public Knowledge Project under the GNU General Public License. International Journal of Gender, Science and Technology, Vol.8, No.3 Stemming the Tide: The Presentation of Women Scientists in CSI This paper evaluates the role of Sara Sidle played by Jorja Fox in CSI: Crime Scene Investigation (CSI) for 15 years, and her female co-stars, allowing us to discuss specific rewards and punishments (Fiske, 1987) assigned over the course of many episodes. -

“Tell-Tale Hearts”

“Tell - Tale Hearts ” Episode #1202 Story by Larry Mitchell Teleplay by Joe Pokaski Dir.: Brad Tanenbaum C S I: Crime Scene Investigation “Tell-Tale Hearts” Episode #1202 Story by Larry Mitchell Teleplay by Joe Pokaski Dir.: Brad Tanenbaum The persons and events portrayed in this film are fictitious. Any Shooting Script similarity to actual persons, living or dead, or any events is unintentional. August 1, 2011 ! MMXI CBS Broadcasting Inc. and Entertainment AB Funding LLC All Rights Reserved. CBS BROADCASTING INC. AND ENTERTAINMENT AB FUNDING LLC ARE THE AUTHORS OF THIS PROGRAM FOR THE PURPOSES OF COPYRIGHT AND OTHER LAWS. No portion of this material may be copied or distributed without the prior consent of CBS Broadcasting Inc. and Entertainment AB Funding LLC. 8/1/2011 “Tell-Tale Hearts” Episode #1202 CAST D.B. RUSSELL CATHERINE WILLOWS NICK STOKES CAPT. JIM BRASS SARA SIDLE GREG SANDERS DR. ROBBINS MORGAN BRODY DAVID HODGES DAVID PHILLIPS CONRAD ECKLIE OFFICER MITCHELL HENRY ANDREWS OFFICER METCALF OFFICER ANDI CANTELVO ALISON MATT JOHN LEE REPORTER #1 REPORTER #2 LESLIE GITIG XIOMARA GARCIA * LONNY GALLOWS MAURICE GALLOWS Featured, Non-Speaking N.D. Uniforms & Detectives N.D. CSIs & N.D. Coroner’s Assistant Anita Chambliss Susan Chambliss Cal Chambliss Fiona Chambliss Reporters and Cameramen Forest Green Lookiloos Construction Workers * REVISED 8/1/2011 “Tell-Tale Hearts” Episode #1202 SETS INTERIORS EXTERIORS CSI Las Vegas Skyline (Stock) Hallway Layout Room Forest Green Sustainable Community Ballistics Empty Street Evidence Locker -

Journal of Research on Women and Gender March 1, 2010

Journal of Research on Women and Gender March 1, 2010 Choice or Chance? Gender, Victimization, and Responsibility in CSI: Crime Scene Investigation Katherine Foss, Middle Tennessee State University In nine seasons of the television program CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, five out of the six original Crime Scene Investigators become crime victims themselves. Nick Stokes is kidnapped and buried alive. Catherine Willows is drugged, abducted, and left naked in a motel. A street gang assaults Greg Sanders after he interrupts their beating up a tourist. The “miniature killer” abducts Sara Sidle and pins her under a car in the desert. And finally, CSI Warrick Brown is murdered in a dark alley by a corrupt police officer. When CSIs become victims, the Las Vegas police force focuses all of its efforts on solving the crime, except in the abduction of Catherine, which goes unreported. In season eight, Catherine accepts a drink from an unknown patron at a local bar. A few scenes later, she wakes up naked and alone in a discount motel. Instead of calling the police, Catherine processes her body for physical evidence and calls Sara Sidle for assistance. Sara asks Catherine why she contaminated the evidence, making it “inadmissible” in court. Catherine replies, “I didn‟t want an official investigation. I just want to know what happened.” By knowingly covering up her crime, Catherine‟s actions suggest that she feels embarrassed and ashamed. The connection between Catherine‟s initial actions (accepting a drink from a stranger) to her desire to cover up the crime, particularly when the other CSIs themselves had reported their victimizations in other situations, suggests that she believes she should have protected herself from becoming victimized. -

Media Effects and the Criminal Justice System: an Experimental Test of the CSI Effect Ryan Tapscott Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2011 Media effects and the criminal justice system: An experimental test of the CSI effect Ryan Tapscott Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Tapscott, Ryan, "Media effects and the criminal justice system: An experimental test of the CSI effect" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 10254. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/10254 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Media effects and the criminal justice system: An experimental test of the CSI effect by Ryan Luke Tapscott A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Psychology Program of Study Committee Douglas Gentile, Major Professor Kevin Blankenship Matthew DeLisi David Vogel Gary Wells Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2011 Copyright © Ryan Luke Tapscott, 2011. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES iv LIST OF FIGURES vii ABSTRACT viii CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 2. CORRELATIONAL STUDY METHODS AND PROCEDURE 33 CHAPTER 3. CORRELATIONAL STUDY RESULTS 49 CHAPTER 4. CORRELATIONAL STUDY SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION 71 CHAPTER 5. EXPERIMENTAL STUDY METHODS AND PROCEDURE 74 CHAPTER 6. EXPERIMENTAL STUDY RESULTS 86 CHAPTER 7. -

The Team: Gil Grissom (William Petersen); Catherine Willows (Marg

The Team: Gil Grissom (William Petersen); Catherine Willows (Marg Helgenberger); Warrick Brown (Gary Dourdan); Nick Stokes (George Eads); Jim Brass (Paul Guilfoyle); Sara Sidle (Jorja Fox); Greg Sanders (Eric Szmanda); Al Robbins (Robert David Hall); Sofia Curtis (Louise Lombard); David Hodges (Wallace Langham); Riley Adams (Lauren Lee Smith); Raymond Langston (Laurence Fishburne); Wendy Simms (Liz Vassey); David Phillips (David Berman); D.B. Russell (Ted Danson); Morgan Brody (Elisabeth Harnois); Julie Finlay (Elisabeth Shue); Henry Andrews (Jon Wellner) The Episodes (2000 – 2015): Season 1 Episode 10 Episode 19 Episode 01 Sex, Lies and Larvae Gentle, Gentle Pilot 22 December 2000 12 April 2001 6 October 2000 Episode 11 Episode 20 Episode 02 I-15 Murders Sounds of Silence Cool Change 12 January 2001 19 April 2001 13 October 2000 Episode 12 Episode 21 Episode 03 Fahrenheit 932 Justice is Served Crate 'n Burial 1 February 2001 26 April 2001 20 October 2000 Episode 13 Episode 22 Episode 04 Boom Evaluation Day Pledging Mr. Johnson 8 February 2001 10 May 2001 27 October 2000 Episode 14 Episode 23 Episode 05 To Halve and to Hold Strip Strangler Friends & Lovers 15 February 2001 17 May 2001 3 November 2000 Episode 15 Season 2 Episode 06 Table Stakes Episode 01 Who Are You? 22 February 2001 Burked 10 November 2000 Episode 16 27 September 2001 Episode 07 Too Tough to Die Episode 02 Blood Drops 1 March 2001 Chaos Theory 17 November 2000 Episode 17 4 October 2001 Episode 08 Face Lift Episode 03 Anonymous 8 March 2001 Overload 24 November 2000 Episode 18 11 October 2001 Episode 09 $35K O.B.O. -

CSI: the New Face of the Male Gaze

Fall 2006 Global Media Journal Volume 5, Issue 9 Article No. 14 CSI: The New Face of the Male Gaze Ami Kleminski Purdue University Calumet Keywords crime drama, CSI (Crime Scene Investigation), male gaze, women in the media Abstract Current television depictions of working women in male-dominated fields represent them from the point of view of the male gaze (Mulvey 1975). This article considers the dangers inherent in audience members’ acceptance and performance of objectifying, stereotypical images of women. The series CSI: Las Vegas will be examined to support this claim. Introduction: Who are You? I have worked in a steel mill in northwest Indiana for ten years. While the mill now employs more women than ever before we are still treated as outsiders in this male-dominated environment. Hence from personal experience I know what it means to be objectified by the male gaze. I am routinely ogled and tested to gauge my reaction to blatantly inappropriate sexual comments. Over the years I’ve cultivated a reputation as a bitch in order to deflect this harassment. But even this label—bitch—does not stop my male co-workers from eyeing me lustily or occasionally inquiring whether I am in a sexual relationship. Indeed, I have been propositioned, asked out on dates by married men, and threatened with physical violence. Decades after the most dynamic years of the twentieth century women’s rights movement, I have no reasonable expectation that my male co-workers will respect me or my privacy. I am the subordinate, sexually degraded Other in the eyes of my fellow workers. -

Skepticaleye

National Capital Area ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ S○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○KEPTICAL EYE • encourages critical and scientific thinking • serves as an information resource on extraordinary Vol. 16, No. 1 claims • provides extraordinary evidence that skeptics are cool 2004 CS TV: Crime Science on Television by Walter F. Rowe, Ph.D. Professor, Department of Forensic Sciences The George Washington University n the last few years television pro- CSI has many positive features. The pro- grams about forensic science have gram focuses on the use of physical evidence become very popular. On cable TV to solve crimes; the witnesses interviewed by channels there are documentary series police often hamper the investigations more coming events 2 such as Forensic Files, The New De- than they help them. Eyewitnesses are often Itectives, and Secrets of Forensic Science. The shown to be mistaken or lying. The problem- prez sez 3 The UFO major networks have dramas such as NBC’s atic nature of eyewitness testimony has been Evidence 4 Law & Order and Crossing Jordan and CBS’s evident to thoughtful investigators for many Precursors of CSI and CSI: Miami. CSI, (Crime Scene In- years. It is valuable to have the lay public fre- Flying Saucers 9 vestigation) now in its third season, is one of quently reminded of its many deficiencies. Lucky Day 10 the most popular programs on television. Cur- On TV and in popular culture in general, Secret Origins rently, it wins its time slot in the Nielsen ratings. educated people are sometimes portrayed as of the Bible 12 The series is set in Las Vegas and follows effete snobs who can barely function in the Bits and Pieces 19 the activities of a team of crime scene investi- real world. -

291399887.Pdf

The Year in Television, 2008 ALSO BY VINCENT TERRACE AND FROM MCFARLAND Encyclopedia of Television Shows, 1925 through 2007 (2009) Encyclopedia of Television Subjects, Themes and Settings (2007) Television Characters: 1,485 Profiles, 1947–2004 (2006) Radio Program Openings and Closings, 193¡–1972 (2003) The Television Crime Fighters Factbook: Over 9,800 Details from 301 Programs, 1937–2003 (2003) Crime Fighting Heroes of Television: Over 10,000 Facts from 151 Shows, 1949–2001 (2002) Sitcom Factfinder, 1948–1984: Over 9,700 Details from 168 Television Shows (2002) Television Sitcom Factbook: Over 8,700 Details from 130 Shows, 1985–2000 (2000) Radio Programs, 1924–1984: A Catalog of Over 1800 Shows (¡999; softcover 2009) Experimental Television, Test Films, Pilots and Trial Series, 1925 through 1995: Seven Decades of Small Screen Almosts (¡997; softcover 2009) Television Specials: 3,201 Entertainment Spectaculars, 1939 through 1993 (¡995; softcover 2008) Television Character and Story Facts: Over 110,000 Details from 1,008 Shows, 1945–1992 (¡993) The Year in Television, 2008 A Catalog of New and Continuing Series, Miniseries, Specials and TV Movies VINCENT TERRACE McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Terrace, Vincent, 1948– The year in television, 2008 : a catalog of new and continuing series, miniseries, specials and TV movies / Vincent Terrace. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 978-0-7864-4391-8 softcover : 50# alkaline paper 1. Television series—United States—Catalogs. 2. Television specials—United States—Catalogs. 3. Television mini-series— United States—Catalogs. 4. Made-for-TV movies—United States—Catalogs. I. -

Copyrighted Material

Chapter 1 Science, Spectacle, and Storytelling My only real purpose is to be smarter than the bad guys, to find the evidence that they did not know they left behind, and make sense of it all. (Grissom, 3.6, “The Execution of Catherine Willows”)1 Near the end of a typical CSI episode, after being confronted with the details of their crime as reassembled by Grissom’s team, over- confident suspects will react with a mixture of admiration and incredulity. They are impressed with the criminalists’ ability to piece together the nar- rative of their crime, but fearful of its effect upon their legal guilt or innocence. “That’s a good story,” they tell the accusing investigator. This final, theatrical act of denial is a common trope of crime fiction, and CSI embraces it, as it does with so many other such generic trap- pings. Its crimes and investigations are, in fact, “good stories,” and even our skepticism as jaded TV viewers is insufficient to derail our enjoyment at the story told. How does CSI do it? How does it work as a platform for mass audi- ence storytelling, especially in an era when that very concept is increas- ingly dubious? It is certainly fair to say that CSI works because it is virtually note-perfect popular television drama, in the historical tradi- tion, regularly delivering an accessible yet intriguing mix of mystery, education,COPYRIGHTED and esprit de corps. It’s undeniably MATERIAL the product of a par- ticularly baroque production style, largely courtesy of Jerry Bruckheimer, the producer who sought to bring his assertive big- screen bravado to television; Danny Cannon, the director who pre- cisely set this tone in the first season; and a meticulous production 99781405186094_4_001.indd781405186094_4_001.indd 8 66/12/2010/12/2010 77:08:38:08:38 AAMM SCIENCE, SPECTACLE, AND STORYTELLING 9 crew, who have materialized these values for over 200 episodes. -

CSI: Crime Scene Investigation - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Pagina 1 Di 20

CSI: Crime Scene Investigation - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Pagina 1 di 20 CSI: Crime Scene Investigation From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia CSI: Crime Scene Investigation (also known as CSI: Crime Scene Investigation CSI: Las Vegas) is an American crime drama television series, which premiered on CBS on October 6, 2000. The show was created by Anthony E. Zuiker and produced by Jerry Bruckheimer. It is filmed primarily at Universal Studios in Universal City, California. The series follows Las Vegas criminalists as they use physical evidence to solve grisly murders in this unusually graphic drama, which has inspired a CSI: Crime Scene Investigation intertitle host of other cop-show "procedurals". An Genre Police procedural, Mystery, immediate ratings smash for CBS, the series mixes Drama, Thriller deduction, gritty subject matter and popular characters. The network quickly capitalized on its Format Live action hit with spin-offs CSI: Miami and CSI: NY. Created by Anthony E. Zuiker CSI was renewed for an eleventh season on May Starring Laurence Fishburne 19, 2010. Marg Helgenberger CSI has been recognized as the most popular George Eads dramatic series internationally by the Festival de Jorja Fox Télévision de Monte-Carlo, which has awarded it Eric Szmanda the "International Television Audience Award Robert David Hall [1][2] (Best Television Drama Series)" three times. Wallace Langham CSI's worldwide audience was estimated to be over David Berman 73.8 million viewers in 2009.[2] Paul Guilfoyle Liz Vassey Contents Lauren Lee Smith William Petersen n 1 Production Gary Dourdan n 1.1 Overview Louise Lombard n 1.2 Conception and development n 1.3 Filming locations Opening theme "Who Are You" by The Who n 1.4 Music n 1.5 Plot Country of origin United States Canada n 2 Cast n 2.1 Main characters No. -

Crime Scene Investigation Through Textual Analysis

Journal of e-Media Studies Volume 2, Issue 1, 2009 Dartmouth College Two Versions of the Victim: Uncovering Contradictions in CSI: Crime Scene Investigation Through Textual Analysis Elke Weissmann …for me it is about the victims. Especially the ones that die too young, too soon. Horatio Caine (David Caruso), CSI: Miami: ‘Bunk’ (1.13) In “Not the Usual Suspects,” Kevin Denys Bonnycastle (2009) bemoans the lack of representation of a racialized underclass in CSI: Crime Scene Investigation (CBS, 2000-present). By focusing on the white middle class as perpetrators, he argues, CSI can represent a neoliberal legitimization of the current American justice system which emphasizes the responsibility of the individual rather than societal factors in the perpetration of crime. Although I agree with Bonnycastle’s assessment of the problematic representation of race in CSI, I do not believe that a changed representation in the perpetrators would have a significant effect, simply because CSI, more generally as a franchise, does not seem to be particularly interested in perpetrators, and hence also marginalizes concerns about motive and reason. Indeed, as the investigators of the three series again and again highlight, their job is to speak for the victims, and hence to put the victim at the center of their investigation. This suggests a remarkable shift in who we think is important when investigating crime. In conventional crime dramas such as Homicide: Life on the Street (NBC, 1993-1999) or Law & Order (NBC, 1994-present),1 the narrative revolves completely around the perpetrator. The central question is ‘whodunit’ which suggests that the investigation is primarily concerned with establishing the perpetrator’s identity.