Feminist Aliens, Black Vampires, and Gay Witches: Creating a Critical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Customizable • Ease of Access Cost Effective • Large Film Library

CUSTOMIZABLE • EASE OF ACCESS COST EFFECTIVE • LARGE FILM LIBRARY www.criterionondemand.com Criterion-on-Demand is the ONLY customizable on-line Feature Film Solution focused specifically on the Post Secondary Market. LARGE FILM LIBRARY Numerous Titles are Available Multiple Genres for Educational from Studios including: and Research purposes: • 20th Century Fox • Foreign Language • Warner Brothers • Literary Adaptations • Paramount Pictures • Justice • Alliance Films • Classics • Dreamworks • Environmental Titles • Mongrel Media • Social Issues • Lionsgate Films • Animation Studies • Maple Pictures • Academy Award Winners, • Paramount Vantage etc. • Fox Searchlight and many more... KEY FEATURES • 1,000’s of Titles in Multiple Languages • Unlimited 24-7 Access with No Hidden Fees • MARC Records Compatible • Available to Store and Access Third Party Content • Single Sign-on • Same Language Sub-Titles • Supports Distance Learning • Features Both “Current” and “Hard-to-Find” Titles • “Easy-to-Use” Search Engine • Download or Streaming Capabilities CUSTOMIZATION • Criterion Pictures has the rights to over 15000 titles • Criterion-on-Demand Updates Titles Quarterly • Criterion-on-Demand is customizable. If a title is missing, Criterion will add it to the platform providing the rights are available. Requested titles will be added within 2-6 weeks of the request. For more information contact Suzanne Hitchon at 1-800-565-1996 or via email at [email protected] LARGE FILM LIBRARY A Small Sample of titles Available: Avatar 127 Hours 2009 • 150 min • Color • 20th Century Fox 2010 • 93 min • Color • 20th Century Fox Director: James Cameron Director: Danny Boyle Cast: Sam Worthington, Sigourney Weaver, Cast: James Franco, Amber Tamblyn, Kate Mara, Michelle Rodriguez, Zoe Saldana, Giovanni Ribisi, Clemence Poesy, Kate Burton, Lizzy Caplan CCH Pounder, Laz Alonso, Joel Moore, 127 HOURS is the new film from Danny Boyle, Wes Studi, Stephen Lang the Academy Award winning director of last Avatar is the story of an ex-Marine who finds year’s Best Picture, SLUMDOG MILLIONAIRE. -

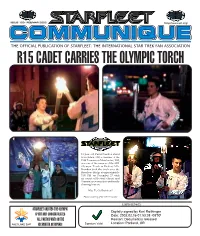

R15 Cadet Carries the Olympic Torch

R15 CADET CARRIES THE OLYMPIC TORCH 15 year old Cadet Brandon Zadel from Salem, NH, a member of the USS Tsunami in Manchester, NH, was one of the runners of the 2001 Olympic Torch in Boston, MA. Brandon took the torch over the Broadway Bridge at approximately 7:00 PM on December 27 with an escort of Boston’s finest and Tsunami crew members and family cheering him on. Way To Go Brandon!! Photos courtesy of the USS Tsunami USPS 017-671 STARFLEET SALUTES THE OLYMPIC SPIRIT AND CONGRATULATES ALL PARTICIPANTS IN THE XIX WINTER OLYMPIAD! THE STARFLEET COMMUNIQUÉ ISSUE 109 – FEBRUARY/MARCH 2002 PAGE 1 STARFLEET Communiqué Volume I, No. 109 Don’t Call Me Edwin!.................................................3 Publisher: STARFLEET, The International Star Trek From the Chief Of Staff................................................4 Fan Association, Inc. Do You Have The Right Stuff?.................................4 P.O. Box 30341 STARFLEET Treasurer Report......................................5 Winston-Salem, NC 27130-0341 2002 STARFLEET Budget.....................................6 Executive Editor Second To One............................................................7 Greg “The Tulip” Trotter STARFLEET Operations...........................................8 Editor: COMM-ING Up Next...............................................9 Kurt “Stinkweed” Roithinger Offi ce Of Graphic Design...............................................9 Assistant Editor: The Shuttlebay.............................................................10 David “Petunia” Pipgras -

“Things Fall Apart” Guest: Jennifer Palmieri

The West Wing Weekly 6.21: “Things Fall Apart” Guest: Jennifer Palmieri [Intro Music] HRISHI: You’re listening to the West Wing Weekly. I’m Hrishikesh Hirway. JOSH: And I’m Joshua Malina. HRISHI: Today we’re talking about episode 21 from season 6, it’s called “Things Fall Apart.” JOSH: This episode was written by Peter Noah and directed by Nelson McCormick. It first aired on March 30th 2005. HRISHI: I don’t believe we’ve heard the name Nelson McCormick before. Is that someone whose directed The West Wing before? JOSH: No, I think not. This is his first of what will turn out to be two episodes of The West Wing. He also directed an episode called “Transition.” Which we’ll get to. Oh we’ll get to it. HRISHI: Joining us later on this episode Jennifer Palmieri, Communications Director for the Hillary Clinton campaign and formerly for the Obama White House. JOSH: What do you think of this one? HRISHI: I, I like the plot of this episode. I think it’s interesting what happens with the convention and the nomination process, but the execution of it, I have issues with here and there. Really just a few moments here and there in the writing. JOSH: I think we will find ourselves in accord as I wrote down ‘Great bones, not enough meat’ HRISHI: Hey look at that. Yeah. That’s a good way of putting it. And before we jump into our discussion, here’s a synopsis from Warner Brothers. “The success of the impeccably organized Republican convention contrasts with the Democrats who look in disarray as the candidates continue to battle to be the Democratic Party Presidential nominee. -

Women at Warp Episode 84: We Left Your Pope on a Moon

Women at Warp Episode 84: We Left Your Pope on a Moon **INTRO MUSIC** Sue: Hi and welcome to Women at Warp a Roddenberry's Star Trek podcast. Join us as our crew of four women Star Trek fans boldly go on our biweekly mission to explore our favorite franchise. My name is Sue and thanks for tuning in. With me today are Andi. Andi: Hello. Sue: And Grace! Grace: Bright blessings nerds. Sue: So today our main topic is going to be that of Kai Opaka, who was only with us really for two episodes technically 4, but makes a big impact on Deep Space Nine. Andi: And our hearts… Grace: And our hearts. Sue: But first we have some housekeeping as usual. This week there is quite a bit of it, so we're going to try and get through it quickly. As always we like to point out that our show is entirely supported by our patrons on Patreon, that's why you never hear an ad on Women at Warp, if you'd like to become a patron you can do so for as little as one dollar per month, and get awesome rewards from thanks on social media to silly watch along commentaries to old pictures of us at conventions as kids, to early releases of episodes. So, if you're interested in that you can visit https://www.patreon.com/womenatwarp. You can also support us by leaving a rating or review on Apple podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts. Next up Parsec Award nominations are open for 2018, the nomination period lasts through June 15th and that can be done if you're interested at http://www.parsecawards.com/. -

Global Upfront New and Returning Series

GLOBAL ANNOUNCES STAR-STUDDED 2021/22 PRIMETIME LINEUP FILLED WITH THE MOST IN-DEMAND NEW PICK- UPS AND RETURNING HIT BLOCKBUSTERS New Global Original Family Law and Franchise Expansions CSI: Vegas, NCIS: Hawai’i, and FBI: International Lead Global’s Fall Schedule The Highly-Anticipated Return of Survivor Joins New Seasons of Hits The Equalizer, Tough As Nails, New Amsterdam, and More New Comedy Ghosts and Audience Favourite United States of Al Bring the Laughs to Global This Fall Stream Anytime with STACKTV or the Global TV App Additional photography and press kit material can be found here. Follow us on Twitter at @GlobalTV_PR To share this release: https://bit.ly/3w3lm3x #CorusUpfront For Immediate Release TORONTO, June 8, 2021 – Ahead of the #CorusUpfront on June 9, Global unveils its 2021/22 programming lineup loaded with exciting series pick-ups and returning established hits. Global’s fall offering promises to deliver a dynamic and diverse schedule filled with thrilling dramas, hilarious comedies, captivating reality television, and much more. Adding 10 new series, including five new primetime series debuting this fall, Global’s schedule features 18 hours of simulcast with four out of seven days entirely simulcast in primetime. Corus’ conventional network offers Canadians a full suite of options for TV lovers looking to stream its blockbuster franchises and hottest new shows in every genre, anytime they want on STACKTV and the Global TV App. “After an unprecedented year, Global is back in full force this fall with a jam-packed schedule of prestigious dramas, powerhouse franchises, and laugh-out-loud comedies,” said Troy Reeb, Executive Vice President, Broadcast Networks, Corus Entertainment. -

TRADING CARDS 2016 STAR TREK 50Th ANNIVERSARY

2016 STAR TREK 50 th ANNIVERSARY TRADING CARDS 1995-96 30 Years of Star Trek 1995-96 30 Years of Star Trek Registry Plaques A6b James Doohan (Lt. Arex) 50.00 100.00 A7 Dorothy Fontana 15.00 40.00 COMPLETE SET (9) 100.00 200.00 COMMON CARD (R1-R9) 12.00 30.00 STATED ODDS 1:72 2003 Complete Star Trek Animated Adventures INSERTED INTO PHASE ONE PACKS Captain Kirk in Motion COMPLETE SET (9) 12.50 30.00 1995-96 30 Years of Star Trek Space Mural Foil COMMON CARD (K1-K9) 1.50 4.00 COMPLETE SET (9) 25.00 60.00 STATED ODDS 1:20 COMMON CARD (S1-S9) 4.00 10.00 STATED ODDS 1:12 2003 Complete Star Trek Animated Adventures Die- COMPLETE SET (300) 15.00 40.00 INSERTED INTO PHASE THREE PACKS Cut CD-ROMs PHASE ONE SET (100) 6.00 15.00 COMPLETE SET (5) 10.00 25.00 PHASE TWO SET (100) 6.00 15.00 1995-96 30 Years of Star Trek Undercover PHASE THREE SET (100) 6.00 15.00 COMMON CARD 2.50 6.00 COMPLETE SET (9) 50.00 100.00 STATED ODDS 1:BOX UNOPENED PH.ONE BOX (36 PACKS) 40.00 50.00 COMMON CARD (L1-L9) 6.00 15.00 UNNUMBERED SET UNOPENED PH.ONE PACK (8 CARDS) 1.25 1.50 STATED ODDS 1:18 UNOPENED PH.TWO BOX (36 PACKS) 40.00 50.00 INSERTED INTO PHASE TWO PACKS UNOPENED PH.TWO PACK (8 CARDS) 1.25 1.50 2003 Complete Star Trek Animated Adventures James Doohan Tribute UNOPENED PH.THREE BOX (36 PACKS) 40.00 50.00 1995-96 30 Years of Star Trek Promos UNOPENED PH.THREE PACK (8 CARDS) 1.25 1.50 COMPLETE SET (9) 2.50 6.00 PROMOS ARE UNNUMBERED COMMON CARD (JD1-JD9) .40 1.00 PHASE ONE (1-100) .12 .30 1 NCC-1701, tricorder; 2-card panel STATED ODDS 1:4 PHASE TWO (101-200) -

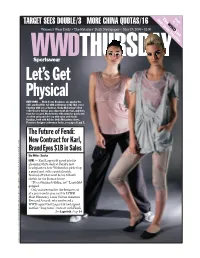

Let's Get Physical

Small-ScreenThe SensationsInside: Pg. 15 TARGET SEES DOUBLE/3 MORE CHINA QUOTAS/16 WWD WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • TheTHURSDAY Retailers’ Daily Newspaper • May 19, 2005• $2.00 List Sportswear Let’s Get Physical NEW YORK — Work it out. Designers are upping the style quotient this fall with activewear looks that cross function with lots of fashion. Stella McCartney’s first collection for Adidas was a knockout at retail, and here, from her second, Modal tanks with polyester pants and a cotton and polyester top with nylon and elastic leggings, both with Adidas Stella McCartney shoes. For more designer activewear looks, see pages 6 and 7. The Future of Fendi: T New Contract for Karl, Brand Eyes $1B in Sales By Miles Socha UMP; STYLED BY DANIELA GILBER UMP; STYLED BY Y/J ROME — Karl Lagerfeld eased into his gleaming white desk at Fendi’s new headquarters here Wednesday, picked up a pencil and, with a quick flourish, finished off what must be his zillionth ANK ARENDS; MAKEUP BY LUCK ANK ARENDS; MAKEUP BY sketch for the Roman house. “It’s a stunning building, no?” Lagerfeld quipped. Only minutes earlier, the designer sat at a press conference next to LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton chairman Bernard Arnault, who confirmed a WWD report that Lagerfeld had signed SA MOLSON/SUPREME; HAIR BY KENSHIN ASANO/FR SA MOLSON/SUPREME; HAIR BY another “long-term” contract with Fendi, See Lagerfeld, Page14 PHOTO BY ROBERT MITRA; MODELS: COLLEEN BAXTER AND MELIS ROBERT PHOTO BY WWD.COM WWDTHURSDAY Sportswear FASHION ™ A slew of designers are adding their names and talent to sport lines, adding 6 fashion to function from the slopes to the courts. -

TCN GO Sun Aug 28, 2011

Schedule Program Guide For TCN/GO Sun Aug 28, 2011 06:00 THUNDERBIRDS Repeat WS G Terror in NYC Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:00 KIDS WB SUNDAY WS G Hosted by Lauren Phillips and Andrew Faulkner. 07:05 THE FLINTSTONES Repeat G Rooms For Rent Fred and Barney's peaceful homes are jeopardized when Betty and Wilma rent rooms to two bongo-playing college students. 07:30 SMURFS Repeat G Soothsayer Smurfette A fortune teller's magical doll dress ends up being Smurfette's new dress of Baby Smurf's birthday party. 08:00 LOONEY TUNES CLASSICS G Adventures of iconic Looney Tunes characters Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Tweety, Silvester, Granny, the Tasmanian Devil, Speedy Gonzales, Marvin the Martian Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner. 08:30 CAMP LAZLO Repeat WS G Weakest Link/ Lumpy Treasure The campers send the Jelly Beans on a "wild goose chase" so they won't bungle the camp inspection! 09:00 SYM-BIONIC TITAN Repeat PG The Ballad of Scary Mary While attending to a "Scary Mary" party, Lance, Ilana and Octus soon find themselves battling against a chameleon-like Mutraddi that can morph into anyone. Cons.Advice: Some Violence 09:30 BEN 10 Repeat WS PG Secret of the Omnitrix During a battle with Animo, a headstrong Ben in hero mode, doesn't listen to reason from Max and Gwen, and gets engulfed in a weird energy light. Cons.Advice: Mild Violence 11:00 POWER RANGERS SAMURAI WS PG Ive Got a Spell on Blue Cons.Advice: Some Violence 11:30 WACKY RACES Repeat G Speeding for Smogland / Race Rally to Raleigh On the set of a medieval-themed movie, Dastardly attempts to trap the racers with the castle gate and drawbridge. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. JA Jason Aldean=American singer=188,534=33 Julia Alexandratou=Model, singer and actress=129,945=69 Jin Akanishi=Singer-songwriter, actor, voice actor, Julie Anne+San+Jose=Filipino actress and radio host=31,926=197 singer=67,087=129 John Abraham=Film actor=118,346=54 Julie Andrews=Actress, singer, author=55,954=162 Jensen Ackles=American actor=453,578=10 Julie Adams=American actress=54,598=166 Jonas Armstrong=Irish, Actor=20,732=288 Jenny Agutter=British film and television actress=72,810=122 COMPLETEandLEFT Jessica Alba=actress=893,599=3 JA,Jack Anderson Jaimie Alexander=Actress=59,371=151 JA,James Agee June Allyson=Actress=28,006=290 JA,James Arness Jennifer Aniston=American actress=1,005,243=2 JA,Jane Austen Julia Ann=American pornographic actress=47,874=184 JA,Jean Arthur Judy Ann+Santos=Filipino, Actress=39,619=212 JA,Jennifer Aniston Jean Arthur=Actress=45,356=192 JA,Jessica Alba JA,Joan Van Ark Jane Asher=Actress, author=53,663=168 …….. JA,Joan of Arc José González JA,John Adams Janelle Monáe JA,John Amos Joseph Arthur JA,John Astin James Arthur JA,John James Audubon Jann Arden JA,John Quincy Adams Jessica Andrews JA,Jon Anderson John Anderson JA,Julie Andrews Jefferson Airplane JA,June Allyson Jane's Addiction Jacob ,Abbott ,Author ,Franconia Stories Jim ,Abbott ,Baseball ,One-handed MLB pitcher John ,Abbott ,Actor ,The Woman in White John ,Abbott ,Head of State ,Prime Minister of Canada, 1891-93 James ,Abdnor ,Politician ,US Senator from South Dakota, 1981-87 John ,Abizaid ,Military ,C-in-C, US Central Command, 2003- -

2018 Star Trek Deep Space Nine Heroes and Villains

2018 Star Trek DS9 Heroes & Villains Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 001 Captain Benjamin Sisko [ ] 002 Odo [ ] 003 Lt. Commander Jadzia Dax [ ] 004 Lt. Ezri Dax [ ] 005 Lt. Commander Worf [ ] 006 Jake Sisko [ ] 007 Chief Miles O'Brien [ ] 008 Quark [ ] 009 Doctor Julian Bashir [ ] 010 Colonel Kira Nerys [ ] 011 Gul Dukat [ ] 012 Vedek Bareil Antos [ ] 013 Jennifer Sisko [ ] 014 Damar [ ] 015 Keiko O'Brien [ ] 016 Weyoun) [ ] 017 Brunt) [ ] 018 Vic Fontaine [ ] 019 Enabran Tain [ ] 020 Nog [ ] 021 Kai Winn Adami [ ] 022 Rom [ ] 023 Martok [ ] 024 The Female Changeling [ ] 025 Kasidy Yates [ ] 026 Sarah Sisko [ ] 027 Leeta [ ] 028 Admiral Alynna Nechayev [ ] 029 Gowron [ ] 030 Shakaar Edon [ ] 031 Elim Garak [ ] 032 Luther Sloan [ ] 033 Kai Opaka Sulan [ ] 034 Grand Negus Zek [ ] 035 Mora Pol [ ] 036 Maihar'du [ ] 037 Lursa and B'Etor [ ] 038 Morn [ ] 039 Tosk [ ] 040 The Hunter [ ] 041 Q [ ] 042 Vash [ ] 043 Ty Kajada [ ] 044 Aamin Marritza [ ] 045 Jaro Essa [ ] 046 Li Nalas [ ] 047 General Krim [ ] 048 Verad [ ] 049 Mareel [ ] 050 Melora Pazlar [ ] 051 Pel [ ] 052 Haneek [ ] 053 Martus Mazur [ ] 054 Alexander Rozhenko [ ] 055 Gul Evek [ ] 056 Cal Hudson [ ] 057 Raymond Boone [ ] 058 Michael Eddington [ ] 059 Grilka [ ] 060 Thomas Riker [ ] 061 Korinas [ ] 062 Detective Preston [ ] 063 Michael Webb [ ] 064 Legate Turrel [ ] 065 Gilora Rejal [ ] 066 Vedek Yarka [ ] 067 The Intendant [ ] 068 Adult Jake Sisko [ ] 069 Goran’ Agar [ ] 070 Tora Ziyal [ ] 071 Faith Garland [ ] 072 Admiral Leyton [ ] 073 Kurn [ ] 074 Onaya [ ] 075 Toman’ torax [ ] 076 Trevean [ ] 077 Arne Darvin [ ] 078 Arandis [ ] 079 Fullerton Pascal [ ] 080 Thrax [ ] 081 Captain Sanders [ ] 082 Ikat'ika [ ] 083 Dr. Lewis Zimmerman) [ ] 084 Arissa [ ] 085 Yelgrun [ ] 086 Kimara Cretak [ ] 087 Ishka [ ] 088 Lwaxana Troi [ ] 089 Admiral William Ross [ ] 090 Joseph Sisko [ ] 091 Mullibok [ ] 092 Varani [ ] 093 Colyus [ ] 094 Rurigan [ ] 095 Kor [ ] 096 Koloth [ ] 097 Kang [ ] 098 Kovat [ ] 099 Lt. -

SYDNEY PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 23Rd June 2013

SYDNEY PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 23rd June 2013 06:00 am Toasted TV G Want the lowdown on what's hip for kids? Join the team for the latest in gaming, sport, pop culture, movies, music and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 06:05 am Monster High G Why Do Ghouls Fall In Love It's Draculaura's 1600th birthday. Toralei, in revenge for not getting invited, hatches a plan to make it Draculaura's worst birthday ever. 07:00 am Toasted TV G Want the lowdown on what's hip for kids? Join the team for the latest in gaming, sport, pop culture, movies, music and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 07:05 am Transformers Prime G Crisscross In Nevada, three young humans, Jack, Miko and Rafael are accidentally caught in the crossfire in a fight between enormous robots that transform into vehicles from the planet Cybertron. 07:25 am Toasted TV G Want the lowdown on what's hip for kids? Join the team for the latest in gaming, sport, pop culture, movies, music and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 07:30 am Pokemon (Rpt) CC G Pokémon is the story of a young boy named Ash Ketchum. Finally having reached the age of 10, he receives his first Pokémon from Professor Oak and sets out on his Pokémon Journey. 08:00 am Toasted TV G Want the lowdown on what's hip for kids? Join the team for the latest in gaming, sport, pop culture, movies, music and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. -

Network Telivision

NETWORK TELIVISION NETWORK SHOWS: ABC AMERICAN HOUSEWIFE Comedy ABC Studios Kapital Entertainment Wednesdays, 9:30 - 10:00 p.m., returns Sept. 27 Cast: Katy Mixon as Katie Otto, Meg Donnelly as Taylor Otto, Diedrich Bader as Jeff Otto, Ali Wong as Doris, Julia Butters as Anna-Kat Otto, Daniel DiMaggio as Harrison Otto, Carly Hughes as Angela Executive producers: Sarah Dunn, Aaron Kaplan, Rick Weiner, Kenny Schwartz, Ruben Fleischer Casting: Brett Greenstein, Collin Daniel, Greenstein/Daniel Casting, 1030 Cole Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90038 Shoots in Los Angeles. BLACK-ISH Comedy ABC Studios Tuesdays, 9:00 - 9:30 p.m., returns Oct. 3 Cast: Anthony Anderson as Andre “Dre” Johnson, Tracee Ellis Ross as Rainbow Johnson, Yara Shahidi as Zoey Johnson, Marcus Scribner as Andre Johnson, Jr., Miles Brown as Jack Johnson, Marsai Martin as Diane Johnson, Laurence Fishburne as Pops, and Peter Mackenzie as Mr. Stevens Executive producers: Kenya Barris, Stacy Traub, Anthony Anderson, Laurence Fishburne, Helen Sugland, E. Brian Dobbins, Corey Nickerson Casting: Alexis Frank Koczaraand Christine Smith Shevchenko, Koczara/Shevchenko Casting, Disney Lot, 500 S. Buena Vista St., Shorts Bldg. 147, Burbank, CA 91521 Shoots in Los Angeles DESIGNATED SURVIVOR Drama ABC Studios The Mark Gordon Company Wednesdays, 10:00 - 11:00 p.m., returns Sept. 27 Cast: Kiefer Sutherland as Tom Kirkman, Natascha McElhone as Alex Kirkman, Adan Canto as Aaron Shore, Italia Ricci as Emily Rhodes, LaMonica Garrett as Mike Ritter, Kal Pennas Seth Wright, Maggie Q as Hannah Wells, Zoe McLellan as Kendra Daynes, Ben Lawson as Damian Rennett, and Paulo Costanzo as Lyor Boone Executive producers: David Guggenheim, Simon Kinberg, Mark Gordon, Keith Eisner, Jeff Melvoin, Nick Pepper, Suzan Bymel, Aditya Sood, Kiefer Sutherland Casting: Liz Dean, Ulrich/Dawson/Kritzer Casting, 4705 Laurel Canyon Blvd., Ste.