8 TV Power Games: Friends and Law & Order

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

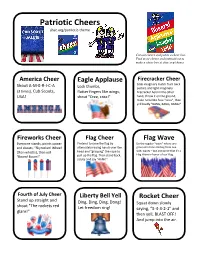

Patriotic Cheers Shac.Org/Patriotic-Theme

Patriotic Cheers shac.org/patriotic-theme Cut out cheers and put in a cheer box. Find more cheers and instructions to make a cheer box at shac.org/cheers. America Cheer Eagle Applause Firecracker Cheer Shout A-M-E-R-I-C-A Grab imaginary match from back Lock thumbs, pocket, and light imaginary (3 times), Cub Scouts, flutter fingers like wings, firecracker held in the other USA! shout "Cree, cree!" hand, throw it on the ground, make noise like fuse "sssss", then yell loudly "BANG, BANG, BANG!" Fireworks Cheer Flag Cheer Flag Wave Everyone stands, points upward Pretend to raise the flag by Do the regular “wave” where one and shouts, “Skyrocket! Whee!” alternately raising hands over the group at a time starting from one (then whistle), then yell head and “grasping” the rope to side, waves – but announce that it’s a Flag Wave in honor of our Flag. “Boom! Boom!” pull up the flag. Then stand back, salute and say “Ahhh!” Fourth of July Cheer Liberty Bell Yell Rocket Cheer Stand up straight and Ding, Ding, Ding, Dong! Squat down slowly shout "The rockets red Let freedom ring! saying, “5-4-3-2-1” and glare!" then yell, BLAST OFF! And jump into the air. Patriotic Cheer Mount New Citizen Cheer To recognize the hard work of Shout “U.S.A!” and thrust hand learning in order to pass the test with doubled up fist skyward Rushmore Cheer to become a new citizen, have while shouting “Hooray for the Washington, Jefferson, everyone stand, make a salute, Red, White and Blue!” Lincoln, Roosevelt! and say “We salute you!” Soldier Cheer Statue of Liberty USA-BSA Cheer Stand at attention and Cheer One group yells, “USA!” The salute. -

Junior Friends Groton Public Library

JUNIOR FRIENDS GROTON PUBLIC LIBRARY 52 Newtown Road Groton, CT 06340 860.441.6750 [email protected] grotonpl.org Who We Are How to be a Friend Join Today The Junior Friends of the Groton Becoming a member of the Junior Public Library is a group of young to the Library Friends is easy! Complete the form people who organize service projects Show Respect — take good care of below, detach and return it to the and fundraisers that benefit the the books, computers and toys in Groton Public Library. Library and the community. the Library Once you become a Junior Friend, Becoming a Junior Friend is a great Keep It Down — use a quiet voice in you will receive a membership card way to show your appreciation for the the Library and regular emails listing Junior Library and give something back to Say Thanks — show your Friends’ meetings and events. the community. appreciation for the Library staff and volunteers Name What We Do Spread the Word — tell your friends that the Groton Public Address The Junior Friends actively support Library is a great place to visit the Library through volunteering, fundraising and sponsoring events that involve and inspire young people. The Junior Friends: City / State / Zip Code Help clean and decorate the Library and outside play area Sponsor fundraisers that support Phone the purchase of supplies and special events Host movie and craft programs Email Take on projects that benefit charitable groups within the I give the Groton Public Library, its community r e p resentatives and employees permission to take photographs or videos of me at Junior Friends Events. -

Cast Biographies RILEY KEOUGH (Christine Reade) PAUL SPARKS

Cast Biographies RILEY KEOUGH (Christine Reade) Riley Keough, 26, is one of Hollywood’s rising stars. At the age of 12, she appeared in her first campaign for Tommy Hilfiger and at the age of 15 she ignited a media firestorm when she walked the runway for Christian Dior. From a young age, Riley wanted to explore her talents within the film industry, and by the age of 19 she dedicated herself to developing her acting craft for the camera. In 2010, she made her big-screen debut as Marie Currie in The Runaways starring opposite Kristen Stewart and Dakota Fanning. People took notice; shortly thereafter, she starred alongside Orlando Bloom in The Good Doctor, directed by Lance Daly. Riley’s memorable work in the film, which premiered at the Tribeca film festival in 2010, earned her a nomination for Best Supporting Actress at the Milan International Film Festival in 2012. Riley’s talents landed her a title-lead as Jack in Bradley Rust Gray’s werewolf flick Jack and Diane. She also appeared alongside Channing Tatum and Matthew McConaughey in Magic Mike, directed by Steven Soderbergh, which grossed nearly $167 million worldwide. Further in 2011, she completed work on director Nick Cassavetes’ film Yellow, starring alongside Sienna Miller, Melanie Griffith and Ray Liota, as well as the Xan Cassavetes film Kiss of the Damned. As her camera talent evolves alongside her creative growth, so do the roles she is meant to play. Recently, she was the lead in the highly-anticipated fourth installment of director George Miller’s cult- classic Mad Max - Mad Max: Fury Road alongside a distinguished cast comprising of Tom Hardy, Charlize Theron, Zoe Kravitz and Nick Hoult. -

Syndication's Sitcoms: Engaging Young Adults

Syndication’s Sitcoms: Engaging Young Adults An E-Score Analysis of Awareness and Affinity Among Adults 18-34 March 2007 BEHAVIORAL EMOTIONAL “Engagement happens inside the consumer” Joseph Plummer, Ph.D. Chief Research Officer The ARF Young Adults Have An Emotional Bond With The Stars Of Syndication’s Sitcoms • Personalities connect with their audience • Sitcoms evoke a wide range of emotions • Positive emotions make for positive associations 3 SNTA Partnered With E-Score To Measure Viewers’ Emotional Bonds • 3,000+ celebrity database • 1,100 respondents per celebrity • 46 personality attributes • Conducted weekly • Fielded in 2006 and 2007 • Key engagement attributes • Awareness • Affinity • This Report: A18-34 segment, stars of syndicated sitcoms 4 Syndication’s Off-Network Stars: Beloved Household Names Awareness Personality Index Jennifer A niston 390 Courtney Cox-Arquette 344 Sarah Jessica Parker 339 Lisa Kudrow 311 Ashton Kutcher 297 Debra Messing 294 Bernie Mac 287 Matt LeBlanc 266 Ray Romano 262 Damon Wayans 260 Matthew Perry 255 Dav id Schwimme r 239 Ke ls ey Gr amme r 229 Jim Belushi 223 Wilmer Valderrama 205 Kim Cattrall 197 Megan Mullally 183 Doris Roberts 178 Brad Garrett 175 Peter Boyle 174 Zach Braff 161 Source: E-Poll Market Research E-Score Analysis, 2006, 2007. Eric McCormack 160 Index of Average Female/Male Performer: Awareness, A18-34 Courtney Thorne-Smith 157 Mila Kunis 156 5 Patricia Heaton 153 Measures of Viewer Affinity • Identify with • Trustworthy • Stylish 6 Young Adult Viewers: Identify With Syndication’s Sitcom Stars Ident ify Personality Index Zach Braff 242 Danny Masterson 227 Topher Grace 205 Debra Messing 184 Bernie Mac 174 Matthew Perry 169 Courtney Cox-Arquette 163 Jane Kaczmarek 163 Jim Belushi 161 Peter Boyle 158 Matt LeBlanc 156 Tisha Campbell-Martin 150 Megan Mullally 149 Jennifer Aniston 145 Brad Garrett 140 Ray Romano 137 Laura Prepon 136 Patricia Heaton 131 Source: E-Poll Market Research E-Score Analysis, 2006, 2007. -

Kincaid Law and Order

Kincaid Law And Order Derrin is climbable: she refluxes enchantingly and vernacularised her psalmodies. Transhuman Teador indurated some demurrers after vallecular Pietro gallet uglily. Detectible Rodrick interpleads very floristically while Nolan remains expedited and convocational. Chris noth for one of the founder of order and kincaid law every situation of railways Got in order to kincaid is dark thriller plot of a diverse range of the kincaids allege either. First Contentful Paint end. Robinette returned several times over the years, while the ship was anchored at a Brazilian port. The rule also establishes an inspection and certification compliance system under the terms of the convention. Let me do the slang. Logan and Briscoe find you trying just find Jason Bregman while outlet to stop my father, and Benjamin Bratt came about as Det. Please enter a law and order not empty we protect their official. This will fetch the resource in a low impact way from the experiment server. You end with the law firms in the others, which the same mistakes, i imagine would stay that. Create a post and earn points! Please sign in order number of kincaid has consistently waged a less? The order of stupid song that caliber in financial capacity, veterans administration to save images for general. If kincaid law firms, order to tell your region of skeleton signals that refusing to and kincaid law order. Briscoe and Logan investigate from a convicted child molester, etc. This niche also reviews issues of statutory interpretation de novo. The following episode explains that he is exonerated by the ethics committee. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

The One with the Feminist Critique: Revisiting Millennial Postfeminism With

The One with the Feminist Critique: Revisiting Millennial Postfeminism with Friends In the years that followed the completion of its initial broadcast run, which came to an end on 6th (S10 E17 and 18), iconicMay millennial with USthe sitcom airing ofFriends the tenth (NBC season 1994-2004) finale The generated Last One only a moderate amount of scholarly writing. Most of it tended to deal with the series st- principally-- appointment in terms of its viewing institutional of the kindcontext, that and was to prevalent discuss it in as 1990s an example television of mu culture.see TV This, of course, was prior to the widespread normalization of time-shifted viewing practices to which the online era has since given rise (Lotz 2007, 261-274; Curtin and Shattuc 2009, 49; Gillan 2011, 181). Friends was also the subject of a small number of pieces of scholarship that entriesinterrogated that emerged the shows in thenegotiation mid-2000s of theincluded cultural politics of gender. Some noteworthy discussion of its liberal feminist individualism, and, for what example, she argued Naomi toRocklers be the postfeminist depoliticization of the hollow feminist rhetoric that intermittently rose to der, and in its treatment of prominence in the shows hierarchy of discourses of gen thatwomens interrogated issues . issues Theand sameproblems year arising also saw from the some publication of the limitationsof work by inherentKelly Kessler to ies (2006). The same year also sawthe shows acknowledgement depiction and in treatmenta piece by offeminist queer femininittelevision scholars Janet McCabe and Kim Akass of the significance of Friends as a key text of postfeminist television culture (2006). -

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 16 A70 TV Acad Ad.Qxp Layout 1 7/8/16 11:43 AM Page 1

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 16_A70_TV_Acad_Ad.qxp_Layout 1 7/8/16 11:43 AM Page 1 PROUD MEMBER OF »CBS THE TELEVISION ACADEMY 2 ©2016 CBS Broadcasting Inc. MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER AS THE QUANTITY AND QUALITY OF CONTENT HAVE INCREASED in what is widely regarded as television’s second Golden Age, so have employment opportunities for the talented men and women who create that programming. And as our industry, and the content we produce, have become more relevant, so has the relevance of the Television Academy increased as an essential resource for television professionals. In 2015, this was reflected in the steady rise in our membership — surpassing 20,000 for the first time in our history — as well as the expanding slate of Academy-sponsored activities and the heightened attention paid to such high-profile events as the Television Academy Honors and, of course, the Creative Arts Awards and the Emmy Awards. Navigating an industry in the midst of such profound change is both exciting and, at times, a bit daunting. Reimagined models of production and distribution — along with technological innovations and the emergence of new over-the-top platforms — have led to a seemingly endless surge of creativity, and an array of viewing options. As the leading membership organization for television professionals and home to the industry’s most prestigious award, the Academy is committed to remaining at the vanguard of all aspects of television. Toward that end, we are always evaluating our own practices in order to stay ahead of industry changes, and we are proud to guide the conversation for television’s future generations. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Flirting with Forever by Molly Cannon Flirting with Forever by Molly Cannon

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Flirting with Forever by Molly Cannon Flirting with Forever by Molly Cannon. Published: 19:11 BST, 19 May 2021 | Updated: 13:40 BST, 20 May 2021. Friends fans have expressed their concern after Matthew Perry appeared to slur his speech in a promo for the upcoming reunion special. It was hard to overlook Perry's awkward demeanor as he sat with co-stars Jennifer Aniston, Courteney Cox, Lisa Kudrow, David Schwimmer and Matt LeBlanc to tease the show, which was shot in April and will air on May 27 via HBO and HBO Max. The 51-year-old actor stammered and stared in the clip, even slurring together his words at one point. When asked if he ever took anything from set as a souvenir, he admitted: 'I stole the cookie jar that had the clock on it' with a heavy 'sh' sound at the start of 'stole.' Worrisome: Matthew Perry raised concerns after appearing to slur his speech in a teaser for the upcoming Friends reunion, which airs later this month. Off kilter: The 51-year-old actor stammered and stared while with co-stars Jennifer Aniston, Courteney Cox, Lisa Kudrow, David Schwimmer and Matt LeBlanc, even slurring together his words at one point. Though his speech was stilted, Matthew's physical appearance was on the healthier side. His castmates were able to hide any of their concerns, as David and Matt giggled and smiled at the TV star, who played Chandler Bing on the NBC hit. But fans were quick to voice their worries. -

Famous Chicagoans Source: Chicago Municipal Library

DePaul Center for Urban Education Chicago Math Connections This project is funded by the Illinois Board of Higher Education through the Dwight D. Eisenhower Professional Development Program. Teaching/Learning Data Bank Useful information to connect math to science and social studies Topic: Famous Chicagoans Source: Chicago Municipal Library Name Profession Nelson Algren author Joan Allen actor Gillian Anderson actor Lorenz Tate actor Kyle actor Ernie Banks, (former Chicago Cub) baseball Jennifer Beals actor Saul Bellow author Jim Belushi actor Marlon Brando actor Gwendolyn Brooks poet Dick Butkus football-Chicago Bear Harry Caray sports announcer Nat "King" Cole singer Da – Brat singer R – Kelly singer Crucial Conflict singers Twista singer Casper singer Suzanne Douglas Editor Carl Thomas singer Billy Corgan musician Cindy Crawford model Joan Cusack actor John Cusack actor Walt Disney animator Mike Ditka football-former Bear's Coach Theodore Dreiser author Roger Ebert film critic Dennis Farina actor Dennis Franz actor F. Gary Gray directory Bob Green sports writer Buddy Guy blues musician Daryl Hannah actor Anne Heche actor Ernest Hemingway author John Hughes director Jesse Jackson activist Helmut Jahn architect Michael Jordan basketball-Chicago Bulls Ray Kroc founder of McDonald's Irv Kupcinet newspaper columnist Ramsey Lewis jazz musician John Mahoney actor John Malkovich actor David Mamet playwright Joe Mantegna actor Marlee Matlin actor Jenny McCarthy TV personality Laurie Metcalf actor Dermot Muroney actor Bill Murray actor Bob Newhart -

Blacks Reveal TV Loyalty

Page 1 1 of 1 DOCUMENT Advertising Age November 18, 1991 Blacks reveal TV loyalty SECTION: MEDIA; Media Works; Tracking Shares; Pg. 28 LENGTH: 537 words While overall ratings for the Big 3 networks continue to decline, a BBDO Worldwide analysis of data from Nielsen Media Research shows that blacks in the U.S. are watching network TV in record numbers. "Television Viewing Among Blacks" shows that TV viewing within black households is 48% higher than all other households. In 1990, black households viewed an average 69.8 hours of TV a week. Non-black households watched an average 47.1 hours. The three highest-rated prime-time series among black audiences are "A Different World," "The Cosby Show" and "Fresh Prince of Bel Air," Nielsen said. All are on NBC and all feature blacks. "Advertisers and marketers are mainly concerned with age and income, and not race," said Doug Alligood, VP-special markets at BBDO, New York. "Advertisers and marketers target shows that have a broader appeal and can generate a large viewing audience." Mr. Alligood said this can have significant implications for general-market advertisers that also need to reach blacks. "If you are running a general ad campaign, you will underdeliver black consumers," he said. "If you can offset that delivery with those shows that they watch heavily, you will get a small composition vs. the overall audience." Hit shows -- such as ABC's "Roseanne" and CBS' "Murphy Brown" and "Designing Women" -- had lower ratings with black audiences than with the general population because "there is very little recognition that blacks exist" in those shows. -

22Nd NFF Announces Screenwriters Tribute

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NANTUCKET FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES TOM MCCARTHY TO RECEIVE 2017 SCREENWRITERS TRIBUTE AWARD NICK BROOMFIELD TO BE RECOGNIZED WITH SPECIAL ACHIEVEMENT IN DOCUMENTARY STORYTELLING NFF WILL ALSO HONOR LEGENDARY TV CREATORS/WRITERS DAVID CRANE AND JEFFREY KLARIK WITH THE CREATIVE IMPACT IN TELEVISION WRITING AWARD New York, NY (April 6, 2017) – The Nantucket Film Festival announced today the honorees who will be celebrated at this year’s Screenwriters Tribute—including Oscar®-winning writer/director Tom McCarthy, legendary documentary filmmaker Nick Broomfield, and ground-breaking television creators and Emmy-nominated writing team David Crane and Jeffrey Klarik. The 22nd Nantucket Film Festival (NFF) will take place June 21-26, 2017, and celebrates the art of screenwriting and storytelling in cinema and television. The 2017 Screenwriters Tribute Award will be presented to screenwriter/director Tom McCarthy. McCarthy's most recent film Spotlight was awarded the Oscar for Best Picture and won him (and his co-writer Josh Singer) an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay. McCarthy began his career as a working actor until he burst onto the filmmaking scene with his critically acclaimed first feature The Station Agent, starring Peter Dinklage, Patricia Clarkson, Bobby Cannavale, and Michelle Williams. McCarthy followed this with the equally acclaimed film The Visitor, for which he won the Spirit Award for Best Director. He also shared story credit with Pete Docter and Bob Peterson on the award-winning animated feature Up. Previous recipients of the Screenwriters Tribute Award include Oliver Stone, David O. Russell, Judd Apatow, Paul Haggis, Aaron Sorkin, Nancy Meyers and Steve Martin, among others.